by Amber Dubin

As a Captain, James T. Kirk has always been known more as a soldier than a diplomat. In the same way that Captain Kirk was forced to move past his initial, violent, problem-solving instincts in "Spectre of a Gun," here, yet another great and powerful alien species drops the crew of the Enterprise into direct contact with a combative, unreasonable opponent, making him take a "diplomatic tiger by the tail" that Captain Kirk must use every tool in his skill set to tame.

The setup is masterfully crafted from the very beginning by what appears to be a solitary alien made of pure energy that presents as a wheel of twinkling lights. Twinkling alien energy, who I will refer to from now on as TAE, is not invisible, but takes pains to silently hover just out of direct line of sight from every group of combatants it takes interest in. The Enterprise does not notice TAE on its first appearance when they beam down to an uninhabited planet, searching for what was supposed to be the ruins of a recently destroyed colony described in a distress signal. Chekov remarks, in confusion, that his readings indicate that there was no evidence of a colony nor an attack. Before the crew has time to process this information, Sulu chimes in over the communicator, warning him that a Klingon ship is approaching. Said ship immediately starts showing signs of distress, quickly becoming disabled by internal explosions to which the Enterprise made no contribution.

Commander Kang, the Klingon starship captain, makes no attempt to understand his situation; he beams down and decks Captain Kirk, yelling that since the federation has committed an act of war against the Klingons by killing 400 of his crew and disabling his ship, he is owed command of the Enterprise. TAE glows a menacing red color, apparently delighted with the increase in hostility. Thus the stage is set before the first credits roll of this episode.

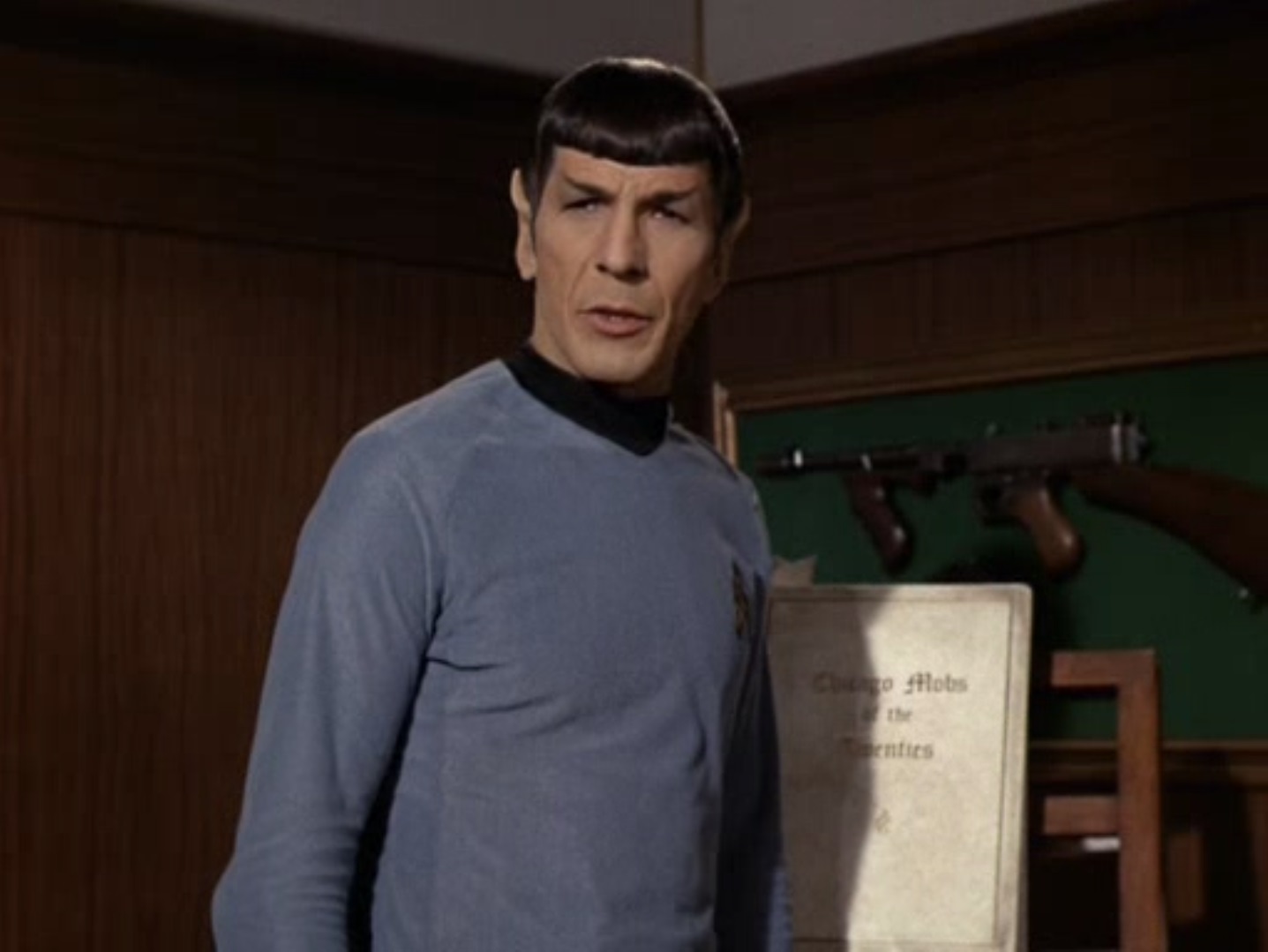

The episode's opening salvo

Captain Kirk displays his newfound diplomatic skills, engaging in dialogue with someone whose assault just knocked him flat on his back. When Kang again demands that Kirk cede control of the Enterprise, our captain calmly replies, “go to the Devil.” Kang smoothly retorts “We have no Devil, Kirk, but we understand the habits of yours,“ whom he intends to emulate by torturing crewmen until Kirk hands over control of his ship.

Suddenly, a strange look comes over Chekov’s face and he jumps at the Klingon commander, practically volunteering to be first on the torture block, incoherently yelling about needing revenge for his brother, Pyotr, who had been killed on the colony they never found. In another clever manipulation, Captain Kirk gets Kang to agree to cease torturing Chekov by promising to beam the Klingons aboard the Enterprise, assuring him that there will be no tricks once they are on the ship. Of course, phrasing it like this left a loophole where he wouldn’t be lying if beaming the Klingons up was the trick—they are stuck in stasis until guards can round them up. Back on the Enterprise, Kirk quarantines the angry Klingon landing party with their distressed ship's remaining crewmen stranded.

A gaggle of steaming-mad Klingons

Before our heroes can figure out what’s going, the Enterprise crewmen start falling one by one under the same spell of violent madness that seized Chekov down on the colony site. Unlike with the Klingon crewmen, this wave of violence is very out of character for the Enterprise crew, and they turn on each other using racist, species-ist and otherwise highly offensive rhetoric against each other, the likes of which hasn’t been used on earth in centuries at this point. Chekov even goes on a slathering rampage where he outright defies Captain Kirk and goes to attack the Klingons to avenge his slain brother. This strangeness becomes particularly significant when Sulu declares that Chekov doesn’t even have a brother, as he's an only child.

Chekov disobeys a direct order.

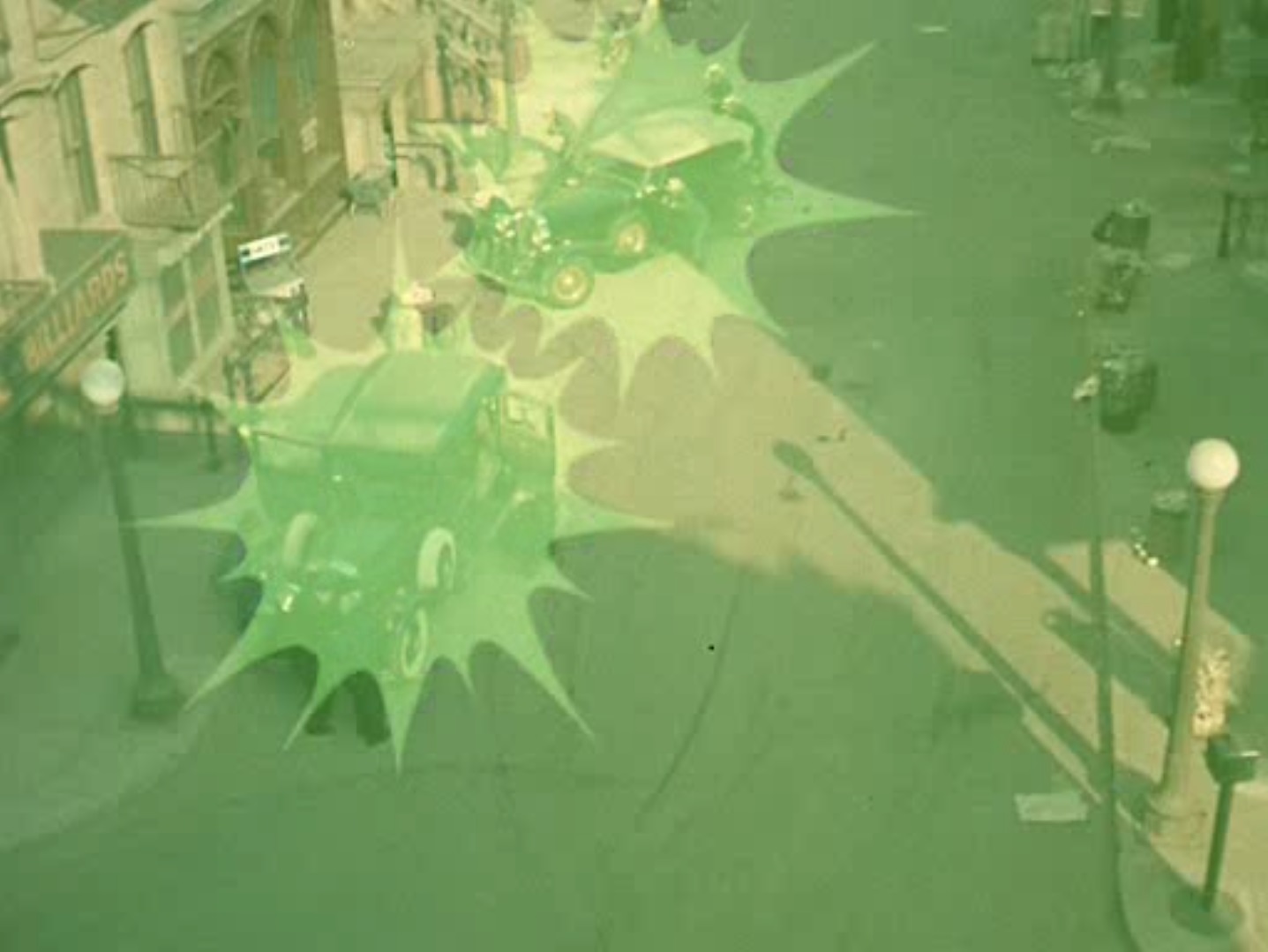

Captain Kirk does the best job of fighting through the madness in order to refocus each crewman one by one towards finding out the root of the issue at hand. It is eventually surmised that TAE is on board, spurring the crewmen to fight and feeding off the negative emotions when its manipulations work and they get at each other’s throats. It is soon discovered that TAE is even more dangerous than originally feared, as it not only can influence the memories and emotions of its victims, but it also has the ability to warp reality itself, healing the scars of the wounded and turning nearly every object at everyone’s disposal into swords, deliberately making every weapon just inefficient enough to prolong conflict and minimize potential fatalities.

Bread and circuses, redux.

In typical Kirk fashion, the seriousness of TAE’s threat doesn’t fully hit him until a female is affected; Kang’s wife, his ship's Science Officer, gets separated from the rest of the group and is set-upon by a completely rabid Chekov. He rips her clothes, but thankfully is interrupted by Kirk and the bridge crew before he can go further. Kirk is justifiably horrified that TAE would be more than willing to push his crew towards that kind of violence. After incapacitating Chekov, Kirk entreats Kang’s wife to join him in uniting her husband and the rest of the Klingons against the real enemy; and it is with great difficulty that he does finally change Kang’s mind and get him to call the rest of the Klingons to a truce. In the end, it’s Kang’s words that finally eject TAE from the ship, as he taunts ”we need no urging to hate humans… only a fool fights in a burning house”

United in defiance.

While it is obvious to see that this episode is once again making a political commentary of our time, this one doesn't rub me the wrong way because the character foils have been fleshed out enough to be likable. Straw men have a tendency to be hollow and weak, but Kang and his wife Mara are anything but that. The Klingons may be violent and aggressive on their face, but they justify their actions with a strong moral backbone and end up proving themselves capable of being reasoned with. Michael Ansara's tremendous presence of voice and body does a phenomenal job of making Commander Kang a formidable yet worthy foe. No slouch herself, Mara shows that she is a leader in her own right, making Kirk work almost as hard to change her mind as her husband's, along the way making some very solid points about Klingon foreign policy. If anything, the Klingons are made to be anti-heroes rather than villains, and in constantly having to take their side against his own men, Kirk shows us the value of humanizing one's enemy, even when that enemy is not human at all.

5 stars.

by Janice L. Newman

When entertainment takes a stance on politics or morality, it’s often a recipe for a bad story. There are plenty of classic parables and fables, of course, but when popular television gets involved in such things sometimes the lesson feels shoehorned in or the plot feels warped around the ‘message’ the writer wanted to send. For example, The Omega Glory and A Private Little War were both attempts to make a point about current political situations, and both were subpar episodes.

“Day of the Dove”, on the other hand, does it right.

This is not a subtle story, yet it maintains a clever mystery plot and dramatic tension right up to the end. The denouement carries a powerful message that I found both shocking and welcome. Shocking, because I didn’t expect to see such blatant anti-war sentiments expressed on prime-time TV. [Janice doesn't watch the Smothers Bros. (ed)] Welcome, because I feel the same way.

There are plenty of intense moments throughout the episode, but the message can be summed up in a few lines of dialogue:

KIRK: All right. All right. In the heart. In the head. I won't stay dead. Next time I'll do the same to you. I'll kill you. And it goes on, the good old game of war, pawn against pawn! Stopping the bad guys. While somewhere, something sits back and laughs and starts it all over again.

MCCOY: Let's jump him.

SPOCK: Those who hate and fight must stop themselves, Doctor. Otherwise, it is not stopped.

MARA: Kang, I am your wife. I'm a Klingon. Would I lie for them? Listen to Kirk. He is telling the truth.

KIRK: Be a pawn, be a toy, be a good soldier that never questions orders.

(Kang looks at the weird light, then throws down his sword.)

KANG: Klingons kill for their own purposes.(Transcript courtesey of chakoteya.)

There is so much conveyed within these few lines. In the context of the rest of the episode, they inspire all sorts of thoughts and questions:

“Question orders.” “Is it wrong to participate in unjust wars?” “Who is benefitting from our wars?” “Who stands to profit and has a vested interest in keeping a war going?” “Are the people with a vested interest also in authority? Do they have control over those in authority?” “Refuse to fight if a war is wrong.” “War may always be wrong.” “Total pacifism may be a possible path.” “If we do not stop hating and fighting, the hating and fighting will not stop.”

These are messages which, if spelled out clearly in almost any other kind of television show, would be unlikely to be allowed on the air. At a time when young men who choose to flee the country rather than accept being drafted are being convicted of treason, telling people to question orders and refuse to fight is risky. Yet the futuristic setting provided by science fiction makes it possible to convey these ideas without the hidebound network pulling the plug or insisting that it be changed. I’m just stunned that Gene Roddenberry let it through, especially after his reputed heavy influence on the script for A Private Little War. I’m not saying I want Star Trek to turn into a ‘message’ show, but I wouldn’t mind a few more episodes like this.

Five stars.

A Third Party

by Lorelei Marcus

As Janice put it, “Day of the Dove” is a ‘message episode’. It’s there to tell you something about life today under the guise of the possible future. Yet unlike my compatriots who saw a cautionary tale of ceaseless fighting in Vietnam and the larger Cold War behind it, I saw a different war entirely.

Star Trek has rarely shown racial tensions between humans and aliens of the Federation. When it is done, it’s for a very specific purpose, like Kirk aggravating Spock in This Side of Paradise. Even the Federation’s disdain for the Romulans and Klingons has less to do with xenophobia and more the fact that neither will agree to reasonable peace terms. Hence why the blatant hatred between not only human and Klingon, but also human and Vulcan, is so jarringly effective in this episode.

Star Trek is the ideal, bigotry-free future—Uhura and Sulu and even Chekov on the bridge are proof of that—but “Day of the Dove” is the closest it gets to reflecting the ugliness of racial tensions in our own world. Cloaked in the veneer of alien and human terms, I saw the hostility and lack of compromise inherent to the Democratic Convention this year, the hatred from man to man over superficial traits.

A scene from the Democratic convention—taken from the Nixon ad that aired during the episode.

Most of all, I saw small prejudices being stoked and inflamed by an outside force, turning anger boiling hot until it nearly exploded into bloody violence. I know that too well. Every step towards peace and equality we take gets slid back when another Wallace or Nixon comes along. Every injustice we commit against the Black man is another reason for him to take a rifle to the streets. Every school that fails to integrate is a generation of Whites who can’t see past the color of skin. And yet, that’s just how Wallace and his ilk want it. They benefit from it.

Wallace preaching hatred from the pulpit.

Perhaps that’s the scariest part: at least in the show, the alien seems to be fomenting hatred out of a need to feed, a necessity. Our politicians do it in the complete service of self-interest. And with the results of the election, tragically, we seem to be dancing right in the palms of their hands.

I often see shades of our world reflected in Star Trek, but never so viscerally. 4 stars.

Go to the Devil

by Joe Reid

“Day of the Dove” was this week’s episode of Star Trek. On first reading that title it evoked religious themes in my mind. I wondered if Star Trek was getting preachy again, the dove being the Christian representation of the Holy Spirit. Like in “Bread and Circuses” where the crew was jubilant that the people of the planet worshiped the son of God. When TV shows try to pass on spiritual virtues, they tend to do it in a ham-fisted way. “Day of the Dove”, although not perfect, does a decent job passing on two themes that I learned in my own religious training. One from the book of Ephesians, chapter 6, verse 12. The other from First Peter, chapter 5, verse 8. So permit me to put on my chaplain's robes as I explore the religious themes I saw in “Day of the Dove”.

Ephesians 6:12 says, “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.” The crew of the Enterprise and that of the Klingon ship were made to think that they were enemies. Expertly manipulated and set upon by another, with the intent to have them fight. The real enemy was the outside force. A powerful alien entity that understood the fears, thoughts, emotions, and technology of each side to create opportunities for conflict. This scripture I quoted explains that no flesh and blood human is your enemy; we are all victims of outside forces that use us against one another. As hard as it was for Kirk and Kang to see that they were being used, it is so much harder for all of us to see that we are literally killing ourselves when we raise arms to harm others. All that does is satisfy the real enemy, that of our very souls.

The second verse that came to mind in this episode, 1 Peter 5:8 says, “Be sober, be vigilant; because your adversary the devil, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour”. At the start of the episode, Kirk told Kang to “Go to the devil!” when Kang slapped Kirk, accusing him of crimes, claiming the Enterprise. As they left that planet, we saw that Kang didn’t have to go to the devil, because a space devil went back to the ship with them. The alien, always near the action, remained just out of sight. It stalked the crew, looking for minds to twist to meet its ends. Kirk displayed powerful sobriety, breaking free from the influence of the alien. Although he could not see the alien, he was able to know of its presence and resist its influence. The message for us is that it takes sober vigilance to prevent wrong actions that may damage other’s lives. It was awareness of the enemy that helped Kirk stay disaster; it may be awareness that people are not the enemy that may help us.

Kirk prepares to preach to the choir.

This episode read like a sermon. One that encouraged brotherhood over bitterness. Which brings us to the close of the episode and yet another verse that came to my mind watching it. That was James 4:7. “Submit yourselves therefore to God. Resist the devil, and he will flee from you.” This was the method Kirk and Kang used to get rid of the unwanted alien influence. They stopped giving it what it wanted, stopped seeing each other as the enemy and told their dancehall mirror ball devil to leave the ship. With both Kirk and Kang saying GO to their devil.

In conclusion, “Day of the Dove” was well acted. It had great costumes and good characterizations of all characters. Sadly, the dialogue at one point was filled with exposition, explaining to the audience what the alien was even though no one explained it to them, which I never love. It caused me to knock the score down a couple of points, but that is to be expected when TV shows—and reviewers—get preachy.

Three stars

Only in the movies

by Gideon Marcus

Despite being a show set in the far future of the 22nd Century, Star Trek has always employed themes from our current era. This has never been truer than in episodes involving the Klingons, the chief adversary of the Federation for which Kirk's Enterprise is employed.

In Errand of Mercy, we saw Commander Kor and Captain Kirk stand shoulder to shoulder, united in their defiance of the superpowerful Organians, who had the temerity to deprive them of their "right" to fight. The threat of the Organians to demolish both adversaries should they escalate their conflict to a general war, was very much a metaphor for the atomic bomb—specifically the newly minted concept of "Mutual Assured Destruction."

Thus, "The Trouble with Tribbles", "Friday's Child", and "A Private Little War"—the Klingons and Federation now fight proxy wars, engage in cloak and dagger exploits, and occasionally skirmish one-on-one. That last title was very much a product of last year, when it looked like we might "win" in Vietnam. Kirk asserted that the only way to prosecute the conflict on the planet of Neural was to arm the hill people so they remain at parity with the Klingon-aided townsfolks.

Contrast that to "Day of the Dove". Kirk and the Klingon commander (beautifully portrayed by "Mr. Barbara Eden", Michael Ansara) once more stand back to back, but they are resisting the urge to fight. It is a beautiful bit of synchronicity that LBJ the night before airdate announced a full bombing pause on Vietnam after three years of incessance. I watched the episode with tears in my eyes: for once, the hope matched the reality. Maybe we were going to stop the cycle of violence after all.

Would that it could always be this easy.

But Trek is science fiction, and we still live in the real world. Dick Nixon won the election this week, South Vietnam has retracted its willingness to participate in the Paris peace talks, and the beat goes on.

This is the second episode in a row (the first being "Spectre of the Gun") that has featured a new Kirk, a diplomat first and a soldier second. I like this new Kirk. I worry that he will run afoul of his superiors, increasingly conflicted, as John Drake was when working for MI6, ultimately becoming The Prisoner. But at least he's fighting for peace, a fight I can 100% get behind.

It's not a perfect episode, a little heavy-handed in parts, but boy did it resonate.

Four stars.

[Come join us tonight (November 8th) for the next thrilling episode of Star Trek! KGJ is broadcasting the show live with commercials and accompanied by trekzine readings at 8pm Eastern and Pacific. You won't want to miss it…]

![[November 8, 1968] A Diplomatic Tiger by the Tail ("Day of the Dove")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681108title-672x372.jpg)

![[October 31, 1968] How the Western was won (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Spectre of the Gun")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681031title-672x372.jpg)

![[October 18, 1968] Little monsters (<i>Star Trek</i>: "And the Children Shall Lead")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681018title-672x372.jpg)

![[October 10, 1968] Going Native (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Paradise Syndrome")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681010title-672x372.jpg)

![[September 26, 1968] Brain drain: (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Spock's Brain")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/680926title-672x372.jpg)

![[June 14, 1968] Men, Women, and Monsters (June 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680614covers-672x372.jpg)

![[April 4, 1968] Time and time again (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Assignment: Earth")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680404title1-672x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1968] I Would Advise Yas ta Keep Watching (<i>Star Trek</i>: "A Piece of the Action")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680118title-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1968] How much for that fuzzy in the window? (<i>Star Trek</i>: The Trouble with Tribbles")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680104title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 28, 1967] Stumbling Bloch (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Wolf in the Fold")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671228title-672x372.jpg)