by Victoria Silverwolf

Compare and Contrast

Two new science fiction novels that fell into my hands are similar in many ways. Both are by British writers and might be classified as action-packed adventure yarns. Each features a rather ordinary hero who gets involved in a secret scientific project of epic proportions. Both protagonists fall in love along the way. Each has a touch of satire and a cynical attitude about politics.

The main difference is that one takes place in the present and the other is set some centuries from now. Let's take a look at the first one.

98.4, by Christopher Hodder-Williams

Cover art by David Stanfield.

Our hero has just lost his job and his live-in girlfriend. He worked as a security expert at a research facility, but certain parts of it were off limits to him. A fellow claiming to work for the United Nations hires him to do some unofficial investigating of the place.

I should mention at this point that everybody the protagonist meets refuses to tell him everything that's going on. I suspect this is a way for the author to keep the reader in suspense. It's also worthy of note that the hero, who is also the narrator, casts a jaundiced eye on the world around him.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union and members of the Warsaw Pact send troops into Czechoslovakia to suppress the liberal reforms known as the Prague Spring. This part of the novel is torn straight from the headlines.

As the Cold War heats up, things get complicated. There's an accident at the facility that causes two ambulances to rush away from the place, although there's apparently only one victim. The hero runs into a mysterious woman who knows more about the situation than she lets on (like a lot of characters in the novel.) She's also suffering from some kind of disease she won't discuss. As you'd expect, love blooms.

Add in a gigantic hidden complex of underground tunnels and automated submarines. The big secret behind everything involves Mad Science at its maddest. The protagonist and a few allies battle to stop World War Three from breaking out, and we'll finally learn what the numerical title means. (I suppose it's also an allusion to George Orwell's famous novel 1984, but that's not all.)

Not the most plausible plot in the world. You have to accept the fact that there could be a secret project extending over many miles without anybody finding out about it. If you can suspend your disbelief, it's a very readable page-turner.

Three stars.

The Weisman Experiment, by John Rankine

Cover art by Richard Weaver.

Let's jump forward hundreds of years. People are rigidly assigned to different levels of society, with their jobs chosen for them. They can't even marry until the powers that be allow them to do so. There are some folks living in the wilderness outside this system. If the previous novel tipped its hat to 1984, this one owes something to Brave New World by Aldous Huxley.

Our hero works for what seems to be the planet's only news agency. His job is only vaguely described, but it seems to be some kind of editing or proofreading position.

The daughter of the boss fancies herself one of those Spunky Girl Reporters from old black-and-white movies. (That's my interpretation, not the author's.) Somehow she came across a reference to something called (you guessed it) the Weisman Experiment. This happened a few decades ago, and the government has repressed all knowledge of it.

The boss tells the protagonist to help his daughter investigate the mysterious experiment. As soon as they set out, somebody tries to kill them. Whenever they track down one of the few surviving people who remember the Weisman Experiment, that person is murdered.

The hero and the daughter (who will, of course, eventually fall in love) are separated by the powers that be before they get too far. The protagonist goes through some brainwashing to straighten him out, but it doesn't quite work.

The rest of the novel takes us to North Africa, where the hero acquires an ally. (This character is a bit embarrassing, as she speaks in an accent and ends almost all her statements with I theenk.) Next we go to an underwater facility, where he's reunited with the daughter. Eventually, we wind up at the estate of an incredibly wealthy fellow, where we finally find out what the heck the Weisman Experiment was all about.

Like the other novel, this is a fast-moving tale with something to say about the way society is set up. Worth reading once.

Three stars.

We have two short novels from very different authors, one being a promising young writer and the other one of the more reliable workhorses in the field. Neither novel is all that good, but at the very least I needed something less demanding after I had recently covered Macroscope.

Grimm's World, by Vernor Vinge

Vinge has written only one or maybe two short stories a year so far, but all of them have been interesting, if not necessarily good. Grimm’s World, his debut novel, is itself an expansion of the novella “Grimm’s Story,” which appeared in Orbit 4 last year. The novel is split into two parts, with the first being “Grimm’s Story,” which as far as I can tell Vinge did not change significantly. If I was just reviewing the first part, I would say it’s fairly good, certainly in keeping with Vinge’s other short fiction. High three to a low four stars.

Unfortunately it doesn’t stop there.

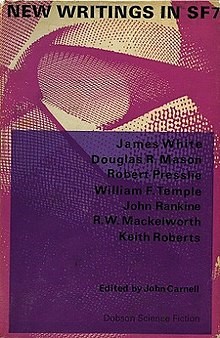

The short of it is that Svir Hedrigs is an astronomy student who gets roped into a scheme by the notorious Tatja Grimm and her crew, those who make the speculative fiction (although here it’s called “contrivance fiction”) magazine Fantasie, a publication that is so old (centuries old, in fact) that its oldest issues seem to have been lost to time, if not for maybe a handful of collectors. The world is Tu, a distant planet that, like Jack Vance’s Big Planet, is vast and yet poor in metals. (Indeed this reads to a conspicuous degree like a Vance pastiche, albeit without Vance’s sardonic humor, and thus it’s not as entertaining.) Something to think about is that characters in an SF story are pretty much never aware that they’re inside a work of SF, and indeed SF as a school of fiction is rarely mentioned, much like how characters in a horror story are often blissfully unaware (for the moment) that they’re birds in a blood-red cage. Yet in Grimm’s World, what we call speculative fiction these days is held as the highest form of literature. It’s a curious case of characters in SF basically realizing that their world itself is SFnal, and therefore the possibilities are near-endless.

Of course the scheme to rescue a complete collection of Fantasie turns out to be a ruse, with Grimm usurping the tyrannical ruler of the single big land mass on this planet, on the falsehood that she is descended from the former monarchy. It’s at this point that the first part ends, and there’s a rather gaping hole in continuity between parts, the result feeling more like two related novellas than a single work. The second part is considerably weaker. What began as a nice planetary adventure turns into something more military-focused, as the people of Tu are terrorized by a race of humanoid aliens, whom Grimm may or may not be in cahoots with. Said aliens take sort of a hands-off approach with the Tu people, provided that their technology doesn’t become too advanced (a high-powered telescope, “the High Eye,” becomes increasingly an object of fascination as the novel progresses), and also that the Tu people reproduce at a rate to the aliens’ liking. What the aliens intend to do with the human surplus is absurd and raises some questions which Vinge never answers. There’s also a love triangle (or perhaps a love square) that I found totally unconvincing, if only because Svir seems to get a hard-on for whatever woman is within his field of vision.

I liked the first part but found the second part a bit of a slog.

Barely three stars.

The Rebel Worlds, by Poul Anderson

Anderson’s writing is comfortable and comforting: rarely surprising, but often (not always) a mild stimulant that can help one during trying times. Just when I think everything might be going to shit, there’s a new Poul Anderson novel—possibly even two of them. The Rebel Worlds is short enough that it could’ve easily made up one half of an Ace Double, except this is from Signet. A few years ago we got Ensign Flandry, which saw the early days in the career of Dominic Flandry, clearly one of Anderson’s favorite recurring characters (although he’s not one of mine). The Rebel Worlds takes place not too long after Ensign Flandry, with Flandry now Lieutenant Commander and with more responsibilities, but still very much the playboy.

Hugh McCormac, a respected admiral of the Empire, is imprisoned, only to break out and go rogue, taking those loyal to him along for the ride. The prison breakout blossoms into a full-on rebellion across multiple worlds, which is a rather big problem for the Empire. Flandry, despite knowing that the Empire is on the brink of collapse and that “the Long Night” will begin soon enough, stays aligned with those in power—perhaps a sentiment Anderson himself shares, given he supports the war effort in Vietnam despite said war effort turning more sour by the week. Indeed Flandry’s seeming contradiction, between his extreme individualism and his allegiance to what he knows is a dying government, is both the core of his character and something he shares with his creator. We also know, from other Flandry stories, that the Empire will in fact soon collapse and that the Long Night, a centuries-long era of barbarism and disconnect across many worlds, will soon commence. And we know that Flandry is in no imminent danger, for better or worse. The real tension, then, lies in McCormac and his wife Kathryn, who has been taken captive by the Empire on the basis that she might cough up valuable info on her husband.

Something I admire about Anderson, despite sharply disagreeing with his politics, is that he’s evidently fond of anti-heroes (Flandry, Nicholas van Rijn, David Falkayn, Gunnar Heim), but he also sometimes concocts anti-villains, in that these characters are technically antagonists but meant to be taken as sympathetic or noble. Despite being a thorn in the Empire’s side, McCormac is basically a good man who cares about those who work for him, never mind he also loves Kathryn very much. Much less sympathetic is Snelund, a planetary governor who is horrifically corrupt, and who also wants to put his filthy hands on Kathryn while she is his prisoner; yet this man also watches over Flandry’s assignment. It should not come as a surprise then that Flandry rescues Kathryn and hides out with her on the planet Dido, which has some unusual alien life. It also shouldn’t be surprising that the two fall in love, although understandably Kathryn still cares for McCormac and isn’t eager to be swept off her feet. (I also must say Anderson tries what I think is a 19th century Southern aristocratic accent with Kathryn, and it’s a bit odd.)

So business as usual for Flandry.

The major problem with The Rebel Worlds is that it’s too short. This is a problem Anderson’s novels sometimes have, but it seems to me that scenes and maybe entire chapters that would have fleshed out the conflict are simply not here. Sure, the plot is basically coherent, but we’re far more often told about things than shown them, to the point where I wonder if Anderson was working with a deadline that he struggled with, even with his near-superhuman writing speed. It’s a fine novel that could have easily been better, with some more time.

A solid three stars.

by Cora Buhlert

A New Chancellor and a New Era

In my last article, I mentioned that West Germany was about to have a federal parliamentary election. Now, that election has come and gone and has led to sweeping political change. Because for the first time since the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, i.e. twenty years ago, the chancellor is not a member of the conservative party CDU.

Since 1966, West Germany has been governed by a so-called great coalition of the two biggest parties, the above mentioned conservative CDU and the social-democratic party SPD. The great coalition wasn't particularly popular, especially among young people, but due to their large and stable majority, they also got things done.

When the election results started coming in the evening of September 28 and the percentages of the vote won by the CDU and SPD respectively were very close, a lot of people expected that this meant that the great coalition would continue. And indeed, this is what many in the CDU and even the SPD would have preferred.

However, SPD head Willy Brandt, former mayor of West Berlin and West German foreign secretary and vice chancellor in Kurt Georg Kiesinger's great coalition cabinet, had different ideas. And so he chose to enter into coalition negotiations not with the CDU, but with the small liberal party FDP. These negotiations bore fruit and the 56-year-old Willy Brandt was sworn in as West Germany's fourth chancellor and head of a social-democratic/liberal coalition government on October 22.

Personally, I could not be happier about this development. I've been a supporter of the SPD for as long as I've been able to vote for them (sadly, I spent the first years of my voting age life under a regime where there were no elections) and I have liked Willy Brandt since his time as mayor of West Berlin. What is more, Willy Brandt is not a former Nazi like his predecessor Kurt-Georg Kiesinger, but spent the Third Reich in exile in Norway and Sweden. Of course, "not a former Nazi" should be a low bar to clear, but sadly West Germany is still infested with a lot of former Nazis masquerading as democrats. And indeed, the one blemish on the otherwise positive results of the 1969 federal election is that the far right party NPD, successor of the banned Nazi Party, managed to gain 3.8 percent of the vote, though thankfully the five percent hurdle keeps them out of our parliament.

In one of his first speeches as chancellor, Willy Brandt said he and his government want to "risk more democracy" and promised long overdue reforms. He also wants to initiate talks with East European governments to thaw the Cold War at least a little. I wish him and his cabinet all the best.

A Magical Mystery Tour: The Unicorn Girl by Michael Kurland

During my latest trip to my trusty import bookstore, I came across an intriguing looking paperback in the good old spinner rack called The Unicorn Girl by Michael Kurland. From the title, I assume that this would be a fantasy tale along the lines of The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle. The Unicorn Girl, however, is a lot stranger than that.

For starters, The Unicorn Girl is actually a sequel to The Butterfly Kid by Chester Anderson, which my comrade-in-arms Kris Vyas-Myall reviewed last year. Like Kid, it's also a book where the author and his best friend, i.e. Michael Kurland and Chester Anderson, are the protagonists.

The Unicorn Girl starts off not in a far-away fantasyland, but in a place that – at least viewed from this side of the Atlantic – seems almost as fantastic, namely a coffeehouse cum performance venue called the Trembling Womb on the outskirts of San Francisco. Our hero Michael (a.k.a. Michael Kurland, the author) is sitting at a table, trying to compose a sonnet, while his friend Chester (a.k.a. Chester Anderson, the author of The Butterfly Kid) is performing on stage, when all of a sudden the girl of Michael's dreams walks in – quite literally, because this very girl has been appearing in Michael's dreams since childhood.

Michael does what anyone would do in that situation: he gets up and talks to the girl. Turns out that her name is Sylvia and that she's looking for her lost unicorn. Michael understandably assumes that Sylvia is playing a joke on him, especially since he had addressed her in the sort of pseudo-medieval language you'd hear at a Renaissance Fair. Sylvia, however, is deadly serious. She tells Michael and Chester that she's a circus performer and that her unicorn Adolphus ran away, when they stepped off the train. There's only one problem: train service into San Francisco ceased six years before. As far as I can ascertain from this side of the Atlantic, this isn't true and San Francisco does have train service, as befits a major metropolis, all which suggests that Michael and Chester live in the future, even though their surroundings seem very much like something you could find in San Francisco right now.

When Michael and Chester ask Sylvia, what year it is, she replies "1936", so Michael and Chester assume that time travel is involved. However, the truth is still stranger than this, for Sylvia seems to have no idea where she is. True, San Francisco today is very different from San Francisco in 1936, but you'd assume that Sylvia would at least recognise the name of the city. The fact that she keeps calling California "Nueva España" is also a clue that Sylvia hails from further afield than our version of 1936.

When Michael, Chester and Sylvia head out to look for the missing unicorn, they are met by some Sylvia's circus friends: Dorothy, an attractive but otherwise normal human woman, Giganto, a cyclops from Arcturus, and Ronald, a centaur. Upon seeing this strange trio, Michael and Chester immediately assume that they are experiencing drug-induced hallucinations – as do two random bystanders. It's a reasonable assumption to make, though two people normally don't experience the same hallucinations, even if they took the same drugs. And Chester swears that he hasn't slipped Michael any drugs…

Methinks we're not in Kansas – pardon, San Francisco – anymore

Before our heroes can get to the bottom of this mystery, they split up to search for the missing unicorn, only to find a flying saucer. There is a mysterious blip and Michael, Chester, Sylvia and Dorotha suddenly find themselves elsewhere and elsewhen, namely in the early Victorian era or rather a version of it that is very reminiscent of Randall Garrett's Lord Darcy stories. I guess they should count themselves lucky it wasn't "The Queen Bee" instead.

The sojourn in the Victorian era according to Randall Garrett ends, when our heroes find themselves falsely accused of jewellery theft (and the way the true culprits accomplished those thefts is truly fascinating). During their escape, there is another blip and our heroes find themselves in World War II in the middle of a battlefield…

For most of its pages, The Unicorn Girl is a picaresque romp through time, space and dimensions. Literary allusions abound, for in addition to the Victorian era according to Randall Garrett, our heroes also briefly visit J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle Earth. It's all great fun, though eventually, there needs to be an explanation for this weirdness. And so, Michael and Sylvia, who have been temporarily separated from Chester and Dorothy, figure out – with the help of Tom Waters, a friend of Michael's and Chester's who'd disappeared earlier – that the blips always happen in moments of danger and crisis. They provoke another blip and finally land in a world that at least is aware that there is a problem with visitors from other times and universes showing up in their world, even if they have no idea why this is happening.

Turns out that all the different time lines and universes are converging, which may well mean the end of this world and any other. Luckily, there is a way to fix this issue and send everybody back to their own universe. The drawback is that solving the problem will be very dangerous. What is more, Michael, Chester and Tom on the one hand and Sylvia, Dorothy and the unicorn (with whom Sylvia has been reunited by now) on the other will return to different universes, even though Michael and Sylvia as well as Chester and Dorothy have fallen in love amidst all the chaos…

A Trippy Delight

The Unicorn Girl is not the sort of book I would normally have sought out, since I'm not a big fan of psychedelic science fiction. However, I'm glad that I read this book, because it's a true delight.

The novel is suffused with humour and wordplay, whether it's the tendency of the Victorians from the Randall Garrett inspired world to speak in very long, very complicated sentences or Michael parodying a wine connoisseur by evaluating plain water. The dialogue frequently sparkles such as when Sylvia asks, "Do you not travel to far-off planets?" and Chester replies, "We barely travel to nearby planets."

A fabulous adventure. Four stars.

![[November 16, 1969] Fun, Frivolity, and Flandry (<i>The Unicorn Girl</i> and more!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691116covers-672x372.jpg)

![[November 14, 1969] To Experiment or Not To Experiment, That is the Question. (<i>The New S. F.</i> & <i>Vision of Tomorrow #2</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Title-Card.png)

![[March 4, 1968] Everything Old is New Again (<i>New Writings in SF-12</i> & <i>Famous Science Fiction</i> Issues #4-6)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Cover-396x372.png)

![[December 4, 1967] Devaluation (<i>New Writings in SF-11</i> & <i>Beyond Infinity</i> December 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Cover-Image-672x372.jpg)

![[December 2, 1967] Women and Men (January 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/IF-1968-01-Cover-672x372.jpg)

President Johnson signing the law allowing women to rise in the ranks.

President Johnson signing the law allowing women to rise in the ranks. What are these people doing in these blobs? Art by Pederson

What are these people doing in these blobs? Art by Pederson![[March 18, 1967] From Both Sides of the Curtain (<i>New Writings in S-F 10</i> & <i>Path into the Unknown</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Banner-672x372.jpg)

![[March 12, 1967] Computerized Futures & Humanity (Out of the Unknown: Season Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Out-of-the-Unknown-2.jpg)

![[June 28, 1966] Scapegoats, Revolution and Summer <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, July 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Impulse-NW-July-1966-672x372.png)

![[April 26, 1966] Inner Space, Romance and Religion <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, May 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Impulse-NW-May-1966-619x372.jpg)

![[February 20, 1966] An Embarrassment of Riches (February Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Montage-Image.jpg)