[January's edition of the Galactoscope offers three novels in two books. Be warned — there's madness afoot!]

by Victoria Silverwolf

Double Your Pleasure, Double Your Fun

Now that you've got the Doublemint Gum jingle running through your head, allow me to explain my reason for annoying you. The Ace Double Series has been going for more than a decade, offering two novels in one. Two short novels, to be sure; some are really novellas. Others are short story collections, as we'll see in today's review. The pair of mini-books are bound in what the printing industry calls dos-a-dos. (Sounds like a square dancing term to me.) That is, each half of the volume is upside down, compared to the other half. Sometimes both parts are by the same writer, sometimes not.

Let's take a look at Ace Double M-109, featuring G. C. Edmondson's first novel, as well as several briefer pieces from the same pen.

Mister Edmondson or Señor Edmondson y Cotton?

I can come up with no better way to introduce the author than by allowing him to speak for himself, in the blurb that comes with the book in question.

I don't know how seriously to take all of that, but it certainly makes for interesting reading. I hope the novel (yes, I'll get around to it eventually) proves to be at least as fascinating.

Appetizers Before the Main Course

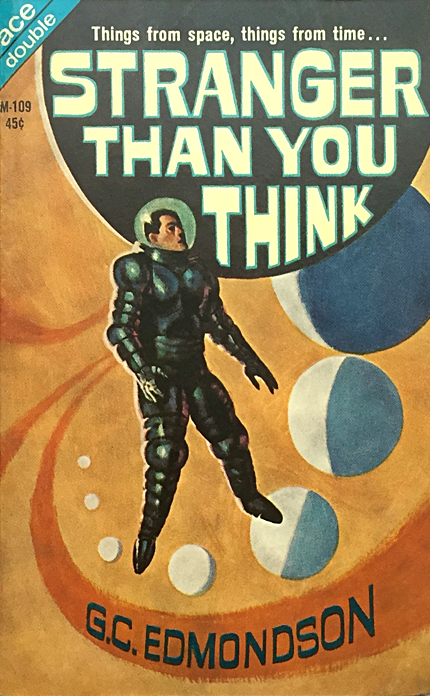

Cover art by Jack Gaughan

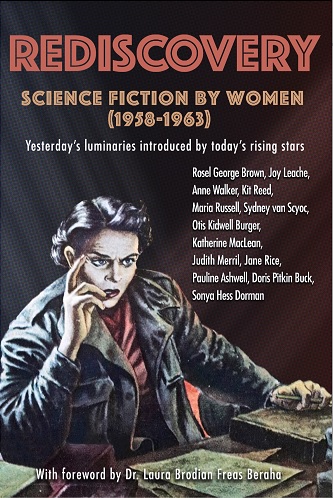

Stranger Than You Think is a collection of all the Mad Friend stories that have appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction to date. Because our Noble Host has already reviewed these tales, I won't go into detail.

Suffice to say that they all feature the narrator and his Mad Friend in rural Mexico, and deal with time travel, alien probes, reincarnation, and such things. The tone is very light, and the stories are about ten percent plot and ninety percent local color. They remind me, a bit, of R. A. Lafferty and Avram Davidson. In general, the series is inoffensive but forgettable.

The Ship That Sailed the Time Stream

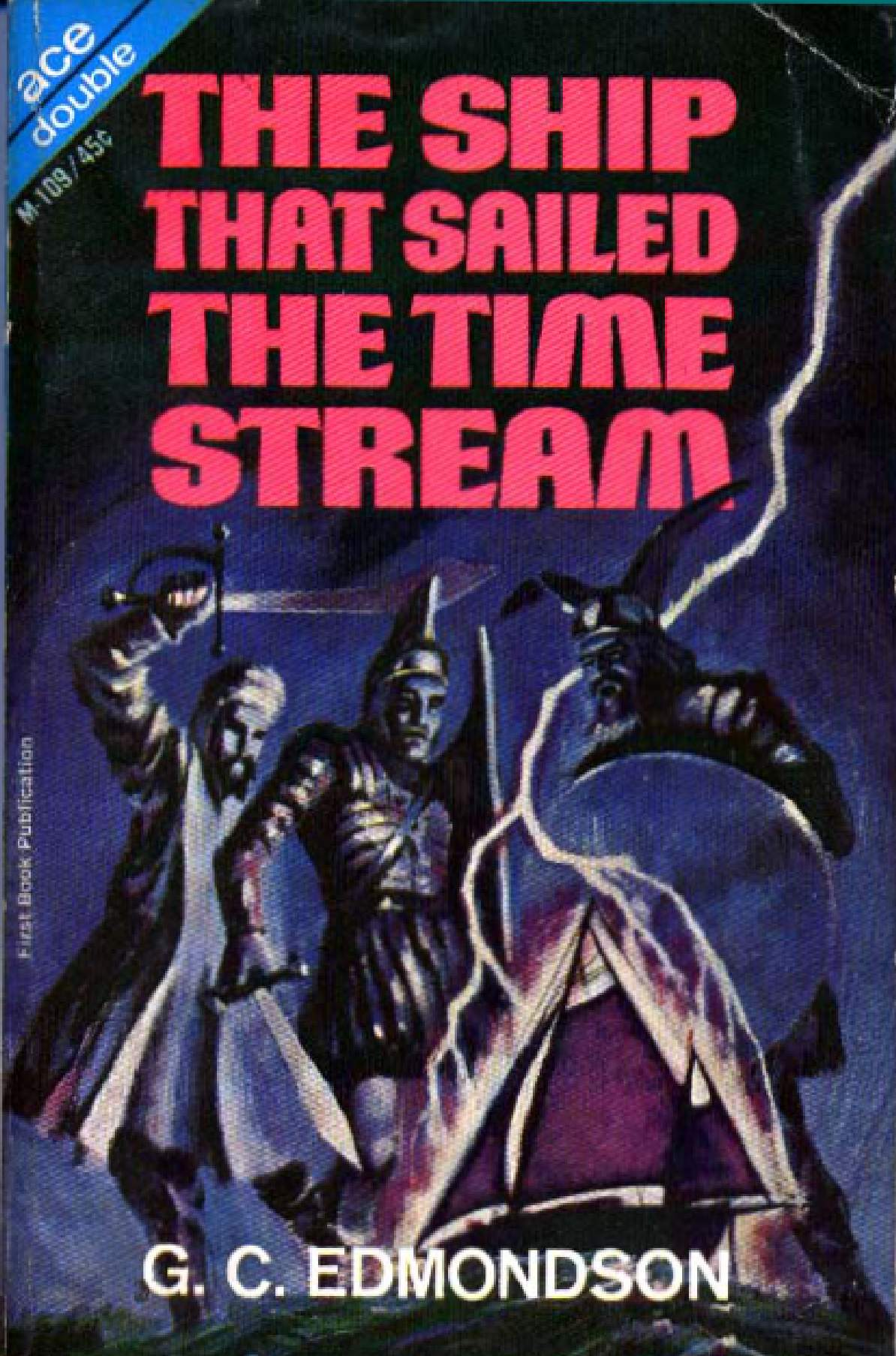

Also by Gaughan

I told you I'd get around to it.

Our hero is Ensign Joseph Rate, commander of the good ship Alice, a unique vessel in the United States Navy of the modern era. You see, Alice is a wooden sailing ship, although she also has a diesel engine for emergency use. The idea is that she can engage in countermeasures against enemy submarines without making sounds that would reveal her position.

At the moment, Alice is engaged in testing new equipment, requiring the presence of an elderly meteorologist and his young assistant. Unknown to his motley crew, Rate is also supposed to investigate criminal activities aboard her.

All of this fades into insignificance, when lighting strikes Alice at the same time the ship's cook is messing around with a new way to distill illicit booze. (Believe it or not, this plays an important part in the plot.)

Full Speed Backwards

If you've read the title of the novel, it won't come as a big surprise to discover that Alice gets zapped back in time a millennium or so, as well as leaving the warm ocean area near San Diego for colder waters, somewhere between Ireland and Iceland. A battle with a Viking raider ensues, followed by a slightly less violent meeting with a merchant ship. Among the cargo she's carrying is a Spanish Gypsy, enslaved by the Norsemen. She winds up aboard Alice, and serves as the novel's main source of sex appeal. Besides that, she's also clever and a tough cookie, so I'll give the author some credit for that.

Here We Go Again

Skipping over most of the first half of the novel, we reach a point where Rate tries to duplicate the circumstances that led to this situation. This doesn't work out very well, because Alice doesn't return to her home, but instead jumps back another thousand years, and winds up somewhere in the Mediterranean.

After encountering Arab slave traders who temporarily take control of Alice, the time travelers eventually wind up on a rocky island, populated by goats and several naked young women, who are more than willing to supply the crew with plenty of wine and other carnal pleasures. There's an explanation for what seems like a sailor's fantasy, which involves another inadvertent visitor from the future, this time the madame of a brothel/speakeasy in 1920's Chicago.

A lot more happens before we reach the end of the novel, including battles with Roman warships and the misadventures of the only religious fanatic aboard Alice, a male virgin who finds himself in intimate situations with more than one alluring lady.

Worth the Voyage?

Although it's impossible to take the novel's version of time travel seriously, the plot doesn't stop for a second, always keeping the reader's interest. As you may have guessed, there's quite a bit of sexual content, which tends to be more teasing than explicit. There's also a lot of violence, given the constant attacks on Alice by just about every vessel that meets her.

The tone of the book ranges from darkly comic to intensely dramatic, with a bit of satire in the form of the religious fanatic. This character may raise some eyebrows among readers of faith, although his version of Christianity is clearly of the extremist variety. The ending raises the possibility of a sequel, but whether such a book will ever appear is up to the tides of time.

Three stars.

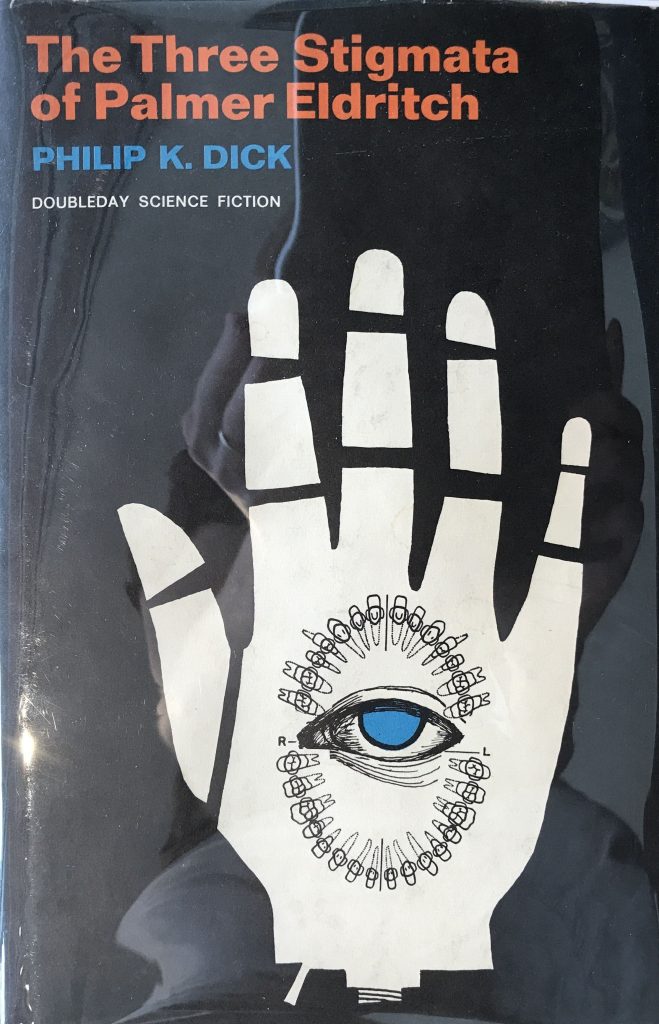

A Little Mental Illness for the New Year (The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldrich by Philip K. Dick)

by Jason Sacks

This is the fourth Philip K. Dick novel released in the last several months, and I’ve read them all. Clearly science fiction’s most surrealistic writer is in the midst of an unusually fecund period, one in which his astounding fiction seems channeled directly from the writer’s brain onto the printed page. And while that unfiltered creativity makes for fascinating reading, Dick’s latest fiction shows him to be wrestling with some intense personal issues, including dislocation and mental health concerns.

Those recent works (The Penultimate Truth, The Clans of the Alphane Moon, Martian Time-Slip and his most recently published novel, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldrich) share a lot in common with each other. All three books demonstrate a mind in constant motion, continually distracted and probing, with ideas seeming to spark from every page in a cascade which starts out as thrilling, becomes tiring, and ultimately proves to be overwhelming. Ideas, interesting and odd, bonkers and basic, philosophical and dully grounded, seem to flow from Mr. Dick as freely as the sweat which constantly seems to be on the foreheads of each and every one of his neurotic protagonists.

Eldrich starts from a template similar to his Dick’s other novels. Most Dick novels feature a neurotic protagonist, and this book is no exception. This time he is named Barney Mayerson and he is a wealthy man in a low-numbered conapt building (a major sign of status) with a great job as the New York Pre-Fash consultant at influential company P.P. Layouts. But Mayerson has problems – oh nellie does he have problems. As the book begins, the businessman wakes up with a hangover, a strange woman in his bed and, most frightening of all, a draft notice which will cause the UN to send him to Mars. That sounds like the beginning of a film noir, but as we follow Mayerson, he slips into a different sort of darkness than the doomed protagonists of our darkest films.

To help him escape the draft, Barney has purchased a robot named Dr. Smile, intended to help Mayerson avoid the draft by making him even more neurotic than he seems. But even the robot isn’t perfect; it calls him by the wrong name and doesn’t seem to pay close attention to Barney, adding to the seemingly endless list of degrading events Barney experiences in the first few pages — and far from the final humiliation he experiences in the book.

Like so many lead characters in recent Dick novels – poor doomed Norbert Steiner in Time-Slip and lovelorn, oblivious Chuck Rittersdorf in Alphane pop immediately to mind – Barney Mayerson is a confused man. He is neurotic, uncertain, perhaps mentally ill. He has tremendous problems relating to the women most important to him, especially his wife. He even gives up all hope of avoiding the draft and instead volunteers to go to Mars, simply to get away from a source of tangled neurotic pain. It is tough to spend time with Steiner, Rittersdorf or Mayerson, because they are so uncertain of themselves despite their apparent success. These are so conscious of their own flaws, their own massive insecurities, that we can understand why these feel rejected by the worlds which surround them. As readers, we want to reject them as well, want to follow characters with some measure of self-assurance, like Trade Minister Tagomi in Dick’s 1963 masterpiece The Man in the High Castle.

Taken one at a time, each of the recent Dick books provide an intriguing portrait of men whose own demons sabotage their own best aspirations. Seen together as a collection of books, it’s hard not to see some authorial autobiography flowing through these characters. After all, if Mr. Dick is writing his books so quickly, how can he avoid writing himself into his stories?

If we take that assertion as fact as part of my essay (and I would be delighted to hear counterarguments in the letters page), then Palmer Eldrich is the most frightening of all Dick’s novels so far. Because at its heart, and in the great thrust of its cataclysmic conclusion, is a break with peaceful reality that actually makes me worry about the author.

Without going too deep into the reasons why – part of the joy of this fascinating book lies in the ways Dick explores his shambolic but complex plot – Barney ends up on Mars and discovers that nearly all the Martian colonists are miserable and drug-addled. Their experience on Mars is so wretched and soul-crushing that only psychedelic drugs, shared among groups of colonists, provide a brief break from their mind-numbing lives.

Barney is responsible for helping a new drug to come to Mars, cleverly called Chew-Z, which promises better highs and more transcendent experiences. But as readers soon discover, the new drug also creates a schizophrenic experience, one in which the terrifying Palmer Eldrich comes to dominate Martian society – and much more – in a way that terrifies everyone who considers it. Eldrich is a terrifying creature, with steel teeth, a damaged arm, and an approach to the world which builds misery.

In truth, Barney Mayerson has unleashed a demon, and it’s not spoiling much in this book to say that by the end you will feel the same fear Barney and the rest of society begin to feel.

Eldrich, thus, is a deeply unsettling book, and fits Dick’s recent output in a way which makes me feel concerned for the author. It is the third out of the four recent novels to deal explicitly with mental illness (in fact, mental illness provides the central storyline of Alphane and a key secondary storyline in Martian Time-Slip). It’s intriguing that Dick sees in science fiction the opportunity to put the readers in the mindset of a man experiencing a schizophrenic break, a psychotic episode, or battling debilitating depression, but the continual presence of such ideas suggests a man whose life is also battling similar breaks.

If Mr. Dick is obsessed with mental illness, does he see that illness in himself when he looks in the mirror? And if we readers purchase Mr. Dick’s books in which mental illness takes a central role, are we aiding his therapy or abetting his continual wallowing?

Palmer Eldrich is not an easy book to read, not once it gets going and we start to realize the depths of Meyerson’s, and Dick’s problems. The plot ambles and wanders and is dense with philosophy and allusion. For a 200-page book, this is no quick Tarzan or Conan yarn. Instead, it is a deeply upsetting, deeply complex look into the disturbed psychology of both its lead character and its author. After consuming so many Dick novels all in succession, I’m craving something much lighter. Neuroses are exhausting.

4 stars

![[January 4, 1965] Madness: 2, Sanity: 1 (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650104covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 5, 1964] Steady as she goes (January 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/651205cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 19, 1964] Ding Dong (December 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641119cover-425x372.jpg)

![[November 9, 1964] Shall We Gather At The River? (January 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Worlds_Of_Tomorrow_v02n05_1965-01_Gorgon776_0001-3-672x319.jpg)

![[September 18, 1964] Split Personality (October 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640918cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1964] It's War! (The October 1964 <i>Galaxy</i> and the 1964 Hugos)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640908cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 16, 1964] Un-Conventional (August 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/640716cover-398x372.jpg)

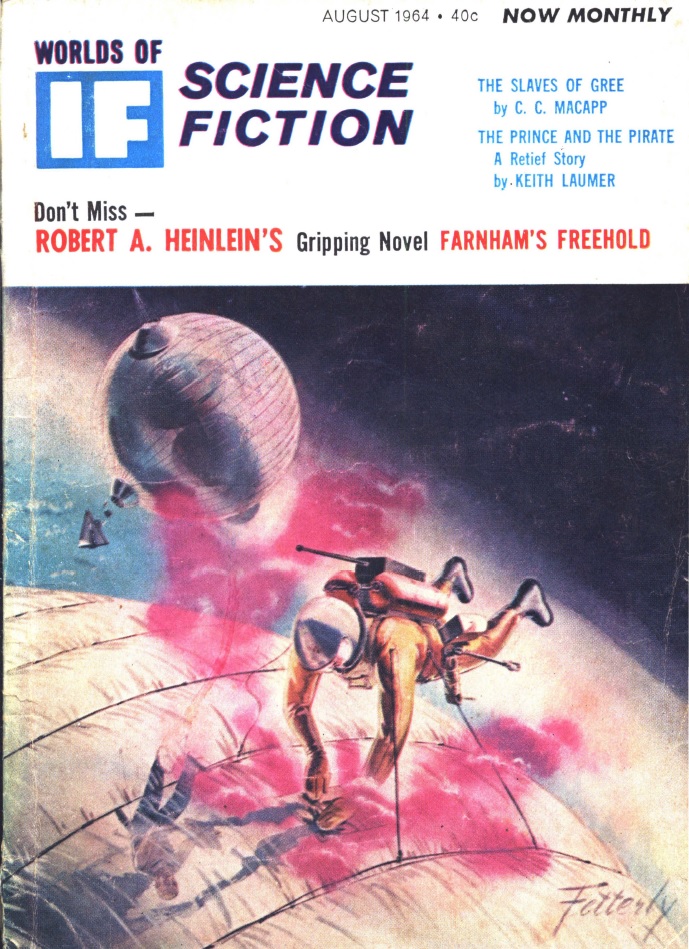

![[July 6, 1964] Busy Schedule (August 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/640706cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 16, 1964] Strangers in Strange Lands (August 1964 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/6312017cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 8, 1964] Be Prepared! (July 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640608cover-672x372.jpg)