by Gideon Marcus

Davey Jones has company

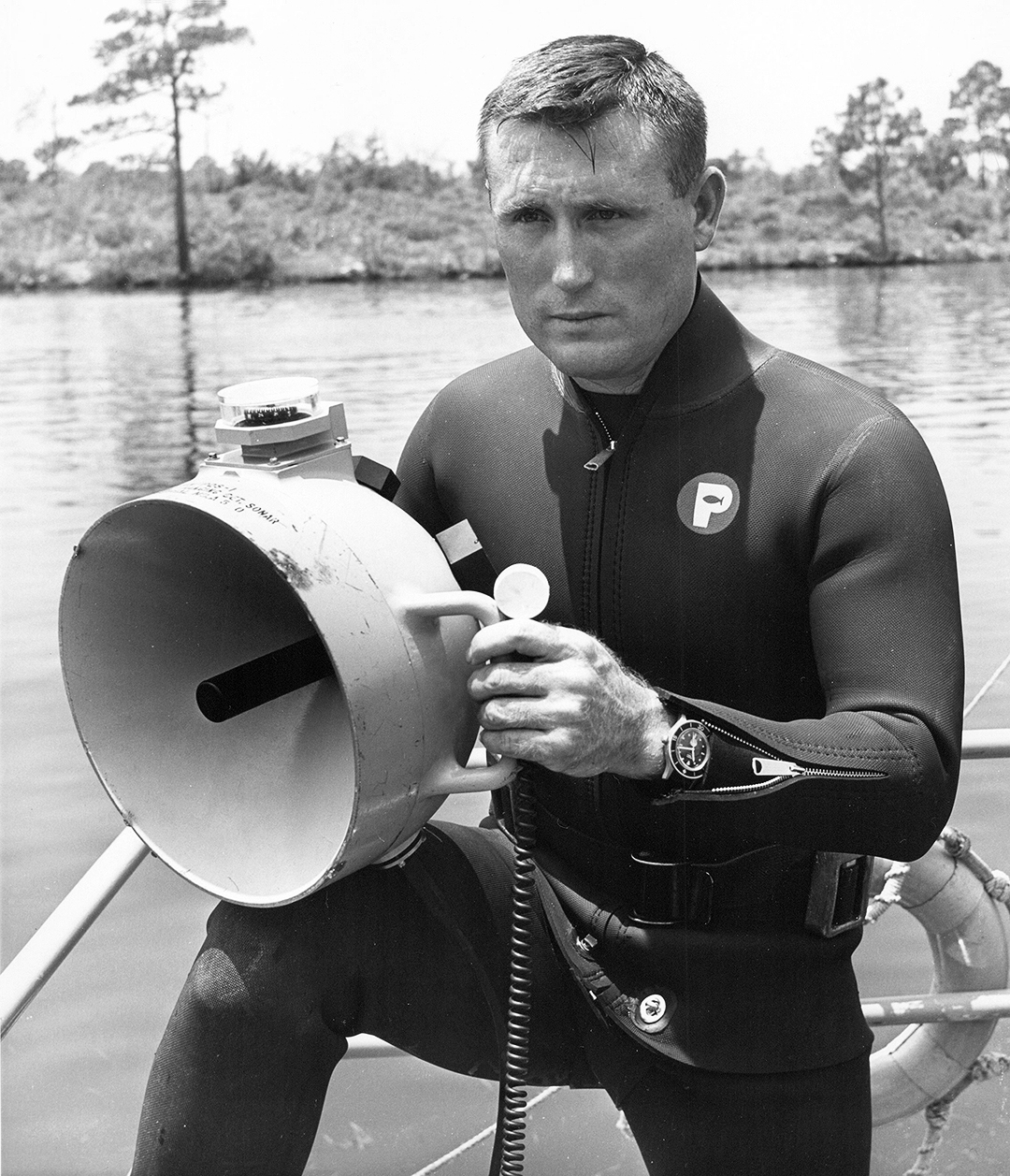

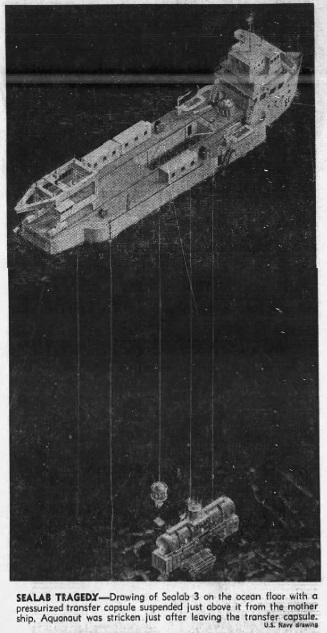

This week, the regional news has been filled with the death of a local hero. Aquanaut Berry L. Cannon, a resident of Sealab III off the coast of La Jolla, died while diving 610 feet to repair a helium leak in his undersea home.

It wasn't a matter of foul play or (so far as is currently known) an accident. The 33 year old Cannon, subject to the rigors of a deep dive and 19 times the pressure out of water, simply succumbed to a cardiac arrest. He was declared dead on arrival at the hospital.

The three other divers who had gone with him had no physical troubles. The repair effort had come shortly after the habitat had been lowered to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean pending long-term habitation by eight aquanauts. Cannon was a veteran of the second Sealab experiment, back in 1965.

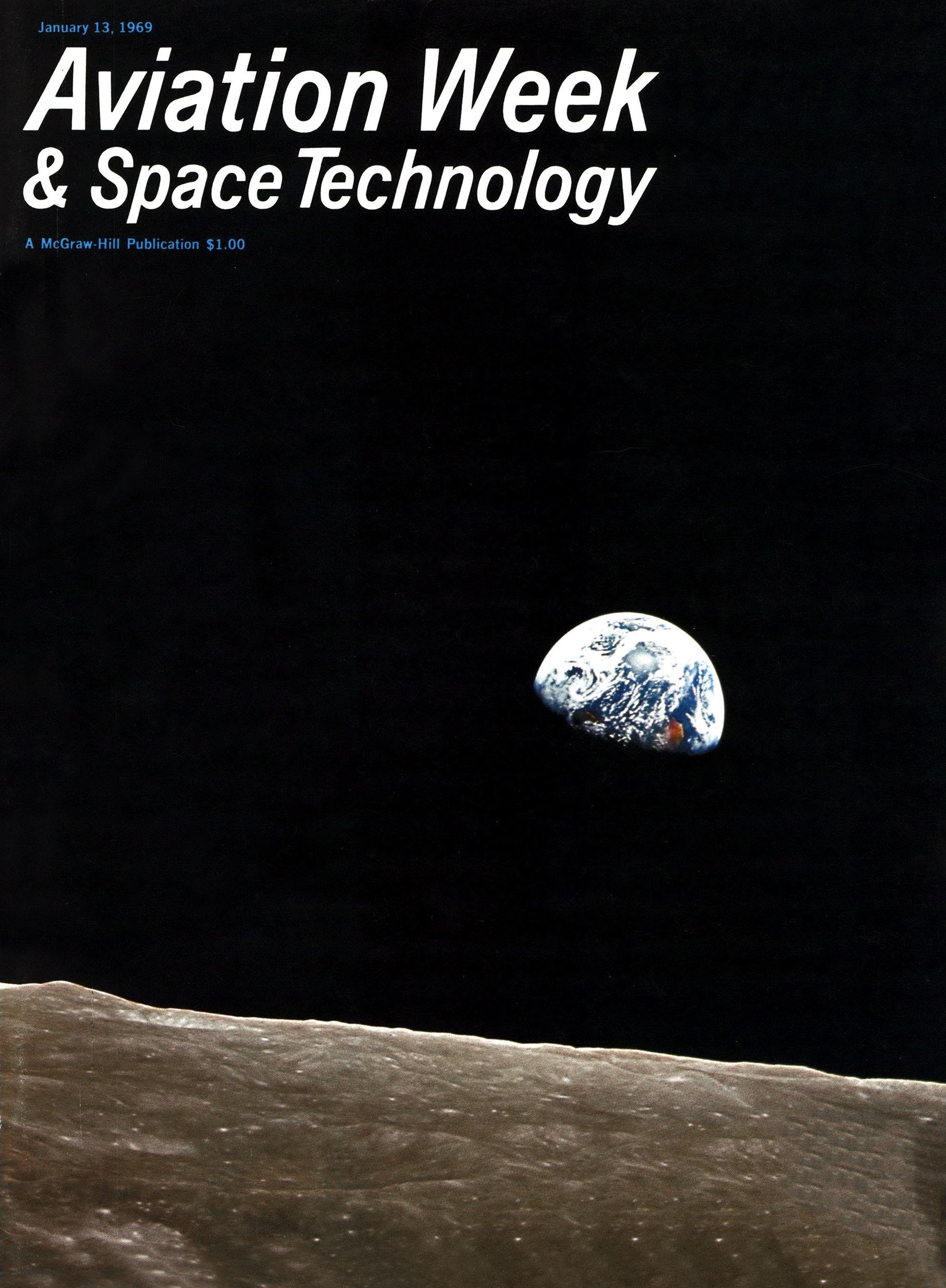

We talk a lot about the space program here on the Journey, but it's important to know that humanity is pushing at all the frontiers, from Antarctica to the sea bottom. And in all such dangerous endeavors, there are tragedies as well as triumphs. Sacrifice is part of the bargain we make for survival of the species, but it never goes down any easier. Especially for his wife, Mary Lou, and their three children…

Davy Jones has company

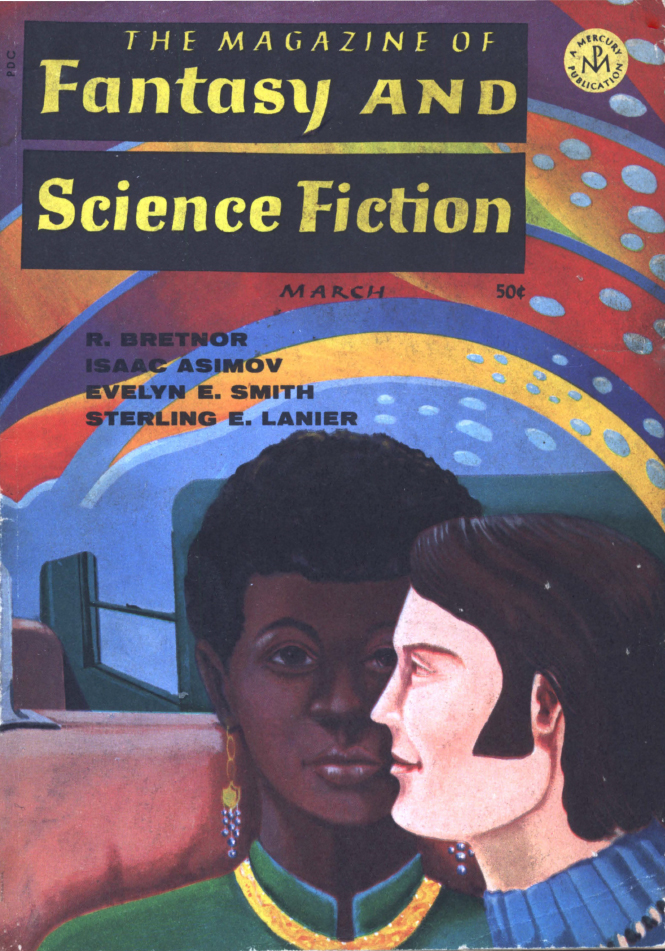

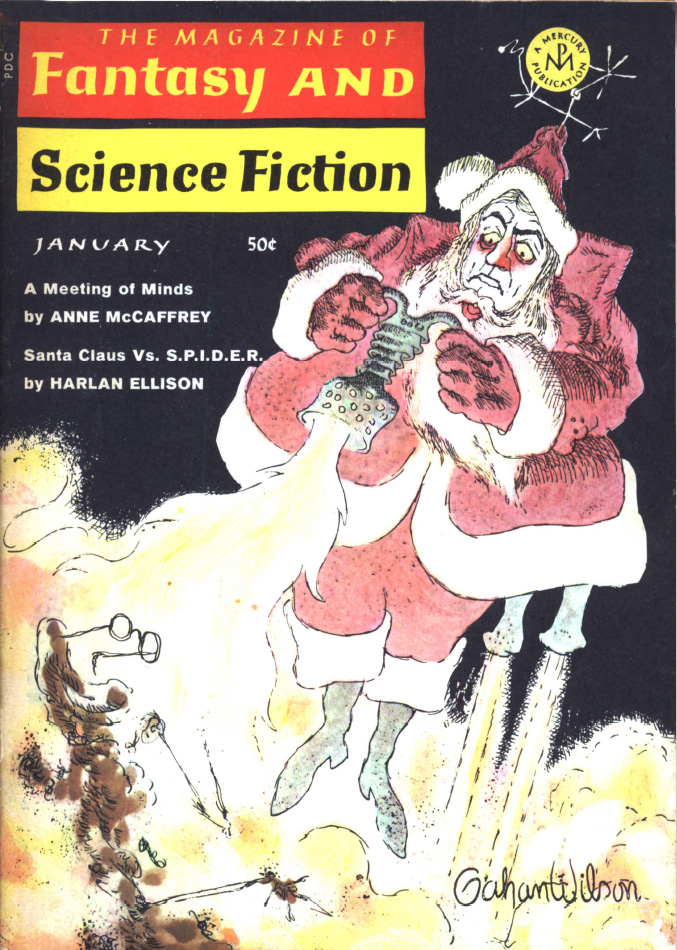

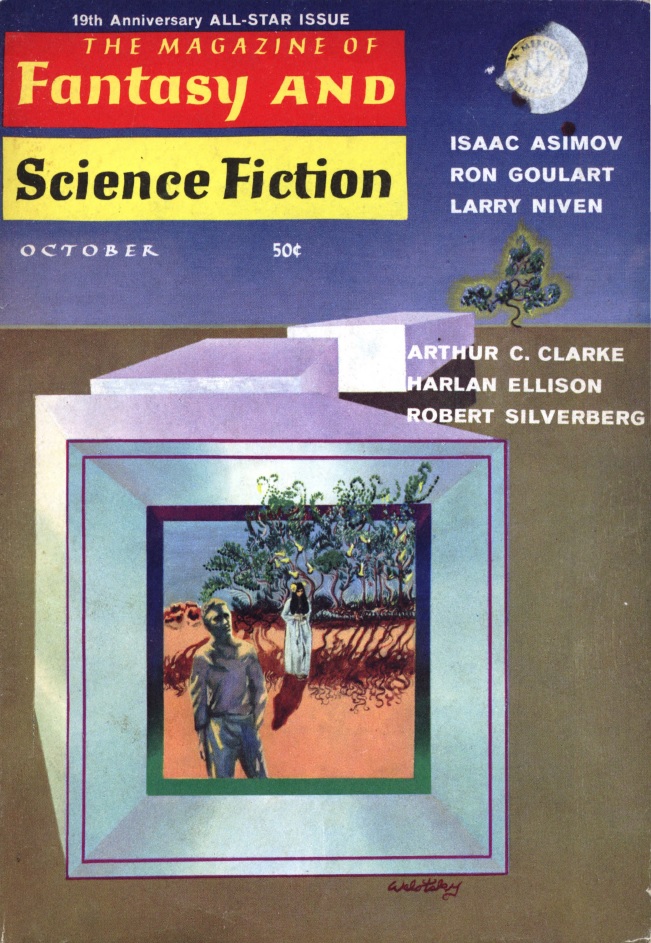

In less tragic news, the latest issue of F&SF is filled with the kind of madcap, surreal adventures you might expect to find on the (sadly cancelled) The Monkees, particularly the first tale:

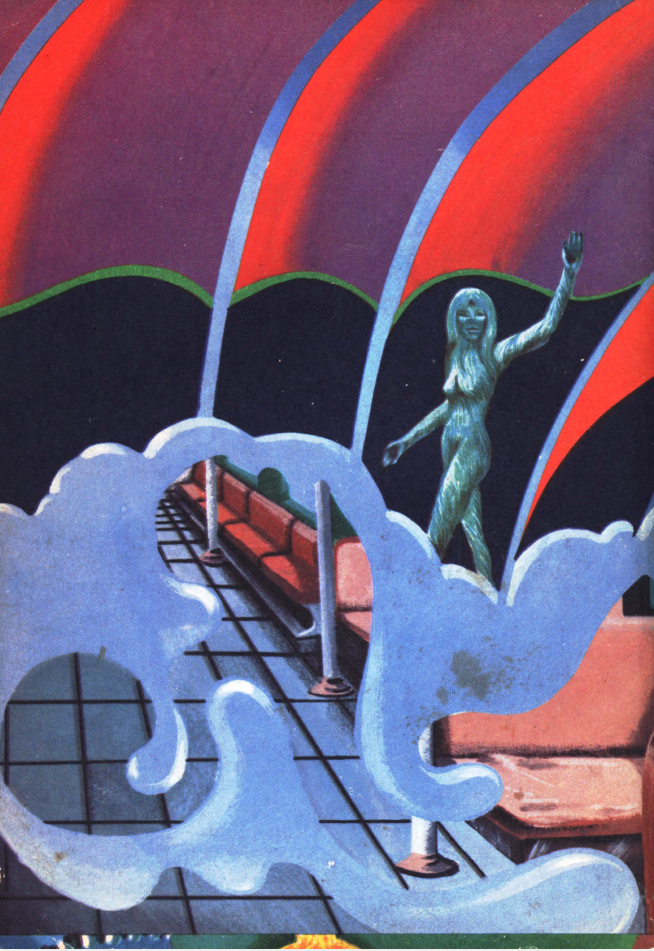

by Ronald Walotsky, illustrating the title story

Calliope and Gherkin and the Yankee Doodle Thing, by Evelyn E. Smith

Like, far out—two Greenwich Village type 17 year-olds, the Jewish "Gherkin" and his Black girlfriend "Calliope" are set up to take the biggest trip of their life. Like, they don't trip out on acid or pot, but literally are snatched for a jaunt to the stars, where they hook up with some of the sexiest green-furred cats you ever did saw.

Was it all an illusion? Or were they really summoned beyond the stars for stud duty? The plot thickens when Calliope begins to show in a motherly way…

This is the first I've seen of Evelyn E. Smith since she was a frequent star of Galaxy in the early '50s. Her chatty, droll style translates pretty well into the modern day, with her madcap, satirical melange of race relations, drug culture, and extraterrestrial high jinks. It runs, perhaps, a bit overlong, and also overdense, but it's not unenjoyable. Welcome back!

Three stars.

Party Night, by Reginald Bretnor

Carce is a scheming woman-user, all veneer and bitterness. When his multi-year attempts to seduce the woman he wants from her husband fails, he goes on a driving jag that plunges him further and further into a night determined to karmically repay him. The pay-off is horrific, though appropriate.

Typical Twilight Zone or Hitchcock stuff, but nicely presented.

Four stars.

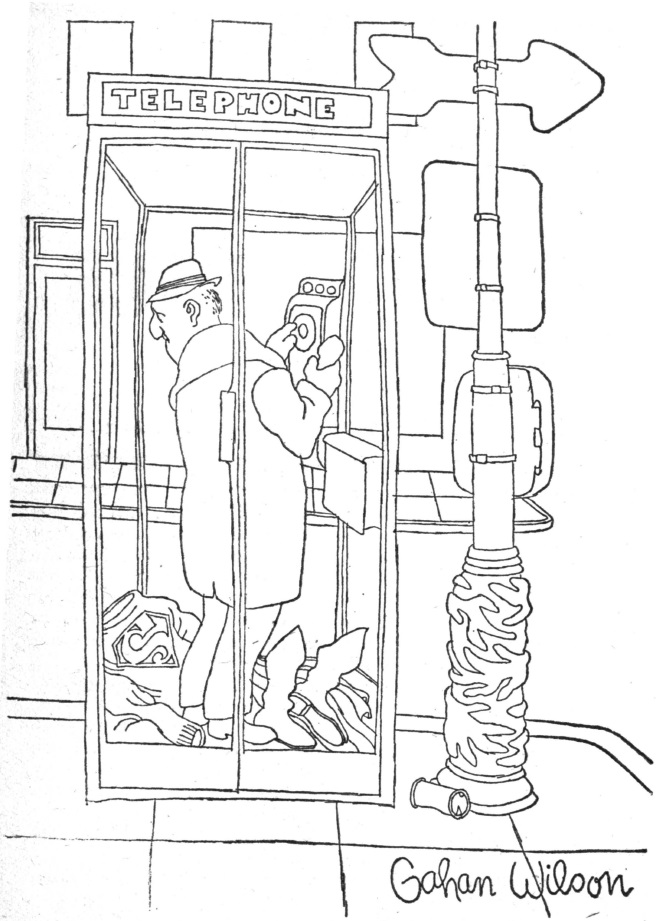

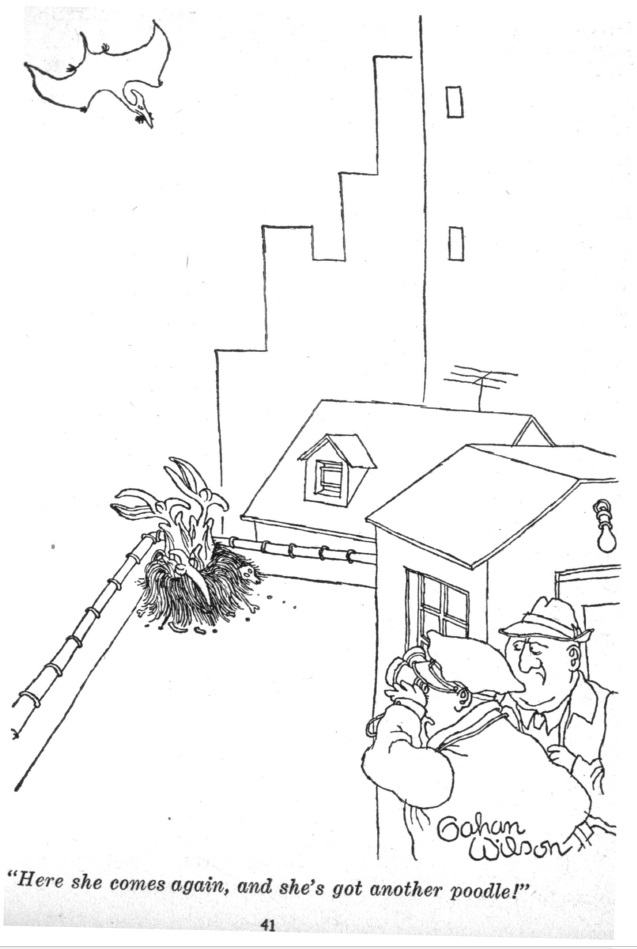

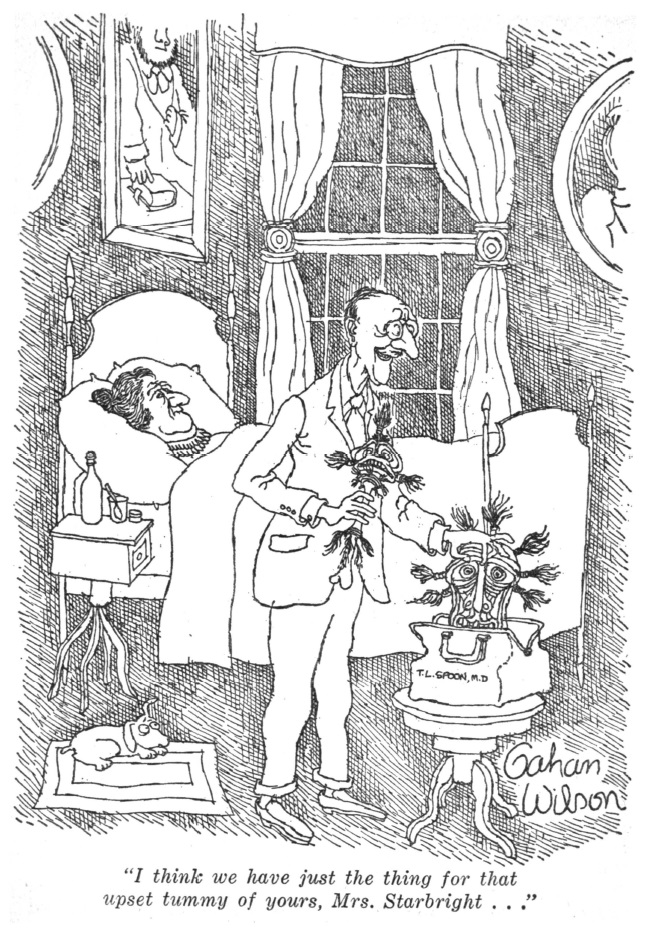

by Gahan Wilson

After Enfer, by Philip Latham

A milquetoast of a man, paralyzed by fear, decides (at the urging of his wife) to find a better job than the museum position he's been stuck in for 16 years. He is recruited to explore the Nth Dimensions with an eye toward opening up tesseractal space for colonization, the world being intensely overcrowded.

We never get no details of the trip; we just know that no one has ever managed to deal with the terror of 3D+ space before. Frankly, without that, the story is just sort of frivolous and a let down.

Two stars.

The Leftovers, by Sterling E. Lanier

The latest Brigadier Ffellowes shaggy-dog-story-told-in-a-pub-setting is the least of the three Lanier has written thus far. This time, it's about a Paleozoic race of sinister, intelligent bipeds that inhabit the southern coast of Arabia, and how the Brigadier and his Sudanese sidekick narrowly escape their pursuit.

Lovecraft was doing such stories better many decades ago. A low three stars.

An Affair with Genius, by Joseph Green

Valence is a gifted biologist, plodding and methodical. For twelve years, he has been estranged from Valerie, a volatile genius in the same field, with whom he had shared a brief but remarkable relationshop. Success tore them apart, as she got the credit for their landmark discovery, and then seemingly abandoned him for a senior professor.

So, when she reappears in his life on the desiccating planet of Tau Ceti 2 where Valence had been researching the colony life forms that eke out a bleak existence, he is shattered, even to the point of contemplating her death.

Fate intervenes in the form of a sudden sand storm, and Valence must save Valerie's life. In the ensuing moment he comes to the realization that without her, he was nothing–just a persistent technician, while Valerie had all the real talent.

But the truth is more complicated; sometimes, it takes yin and yang to make a complete unit…

This is a beautiful story. Perhaps I'm just the intended audience, but I loved it. Five stars.

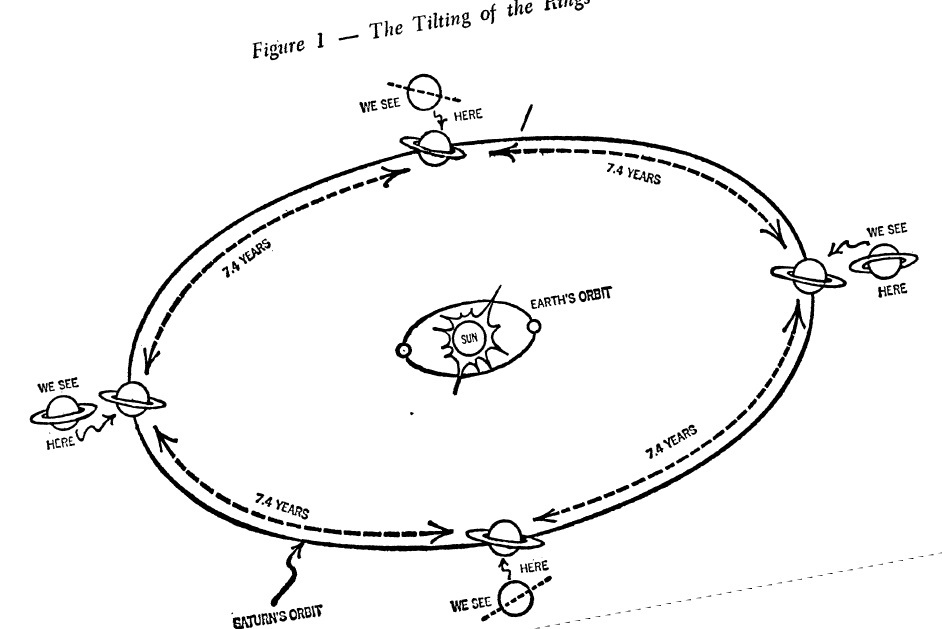

Just Right, by Isaac Asimov

The Good Doctor offers up, this month, a piece on the square-cube law—explaining why it's not possible to simply shrink or grow the scale of an object and think it will be subject to the same physical laws. He lambasts the TV show Land of the Giants in the process, as is appropriate.

It's a good article, and the final sentence is hilarious. Four stars.

The Day the Wind Died, by Peter Tate

An old man squats on his roof, in a senile dream reliving his days as an ace in World War I, planning to soar on artificial wings he has just purchased. His son Charlie, a harried weatherman, drops a mirror while shaving. His son notices that the wind around their house has abruptly stopped, and he believes his father caused it. He tells his friends.

And the plainclothes agents for the Bureau for the Investigation of Weather Incidents takes notice, certain that Charlie has stilled the wind for nefarious purposes—to ensure his father falls to his death when he takes to the sky on his wings.

Is Charlie a wizard? Who are these agents? Is this our world at all?

A surreal, rather puzzling story. I give it three stars.

Benji's Pencil, by Bruce McAllister

Maxwell, an English teacher, wakes from cold sleep two centuries hence only to find the world crammed with people and utterly lacking in color. But beauty exists as long as poetry is possible, and Maxwell makes sure that his multi-great grandson has the power of simile before the teacher is sent to the euthanasia chamber at age 70.

The story is written in a hopeful tone, but the subtext is entirely cynical. As usual, McAllister shows promise, but there is still a rawness that holds his work back from greatness.

Three stars.

Coming up for air

A good issue, this, and thankfully, no one had to risk perishing to explore these frontiers. Then again, perhaps it is prose daydreams like the ones in F&SF that drive men to explore onward. No coin is without two sides, I suppose.

Here's to future expeditions, both literary and actual, and safe travels to all who undertake them!

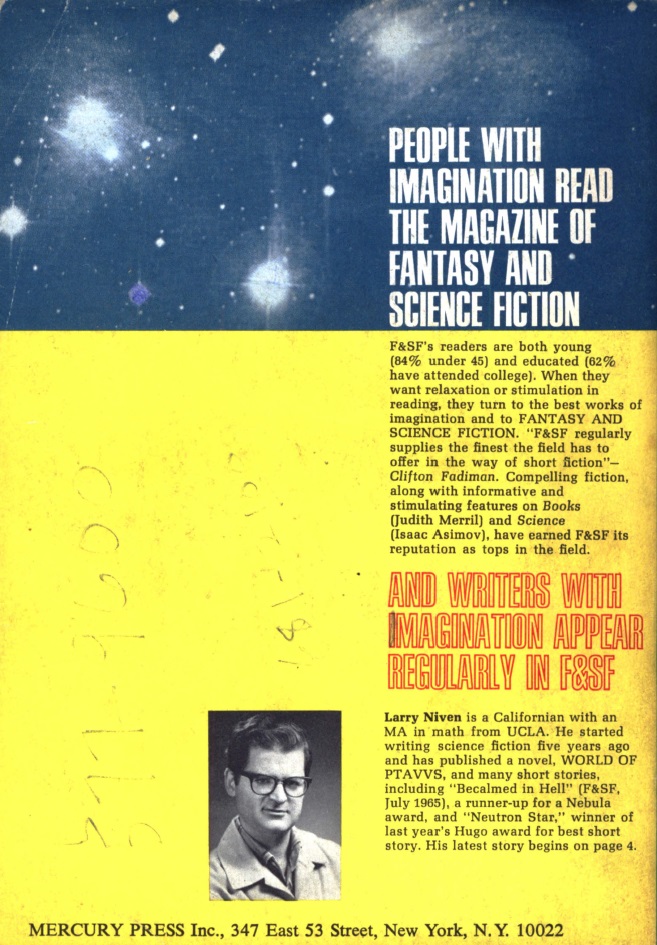

by Ronald Walotsky

![[February 22, 1969] Good and Bad Trips (March 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/690222cover-665x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1969] (February 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690118cover-663x372.jpg)

![[December 22, 1968] What wonders await? (January 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681222cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 20, 1968] Transitory and lasting pleasures (December 1968 <i>F&SF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681120cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 2, 1968] Role Models (December 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/IF-1968-12-Cover-672x372.jpg)

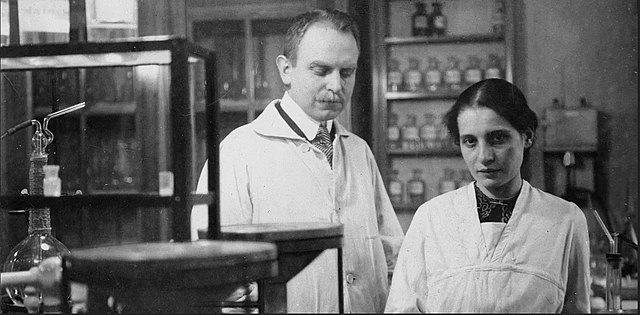

Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner circa 1912.

Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner circa 1912. Lise Meitner in 1963.

Lise Meitner in 1963. A previously unknown piece by the late Hannes Bok, probably the last new Bok cover ever.

A previously unknown piece by the late Hannes Bok, probably the last new Bok cover ever.![[October 20, 1968] Giants among Men (November 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681020cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 20, 1968] It comes and goes (October 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/680920cover-651x372.jpg)

![[August 20, 1968] A tale of two issues (September 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680820cover-659x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1968] Shades and Shadows (August 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680722cover-664x372.jpg)

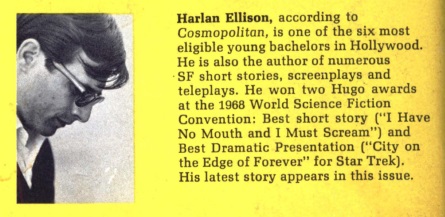

![[June 26, 1968] To far off lands (July 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680620cover-451x372.jpg)