by David Levinson

It seems like the world gets a little smaller every day. Jet planes are gradually replacing larger propeller-driven planes in the passenger market, reducing the time it takes to get from one place to another. As they become more ubiquitous even the middle class may be able to travel like the jet set. Communications satellites are making it possible for news to spread faster, and we can even see some events on television as they happen on the other side of the world.

On the other hand, the world seems to be getting bigger, too. We hear constantly about remote places where this conflict or that independence is taking place. The wealth of human knowledge is growing so fast, it’s almost impossible to keep up. Growing, shrinking, let’s look at some things that have done one or the other lately.

A long shortcut

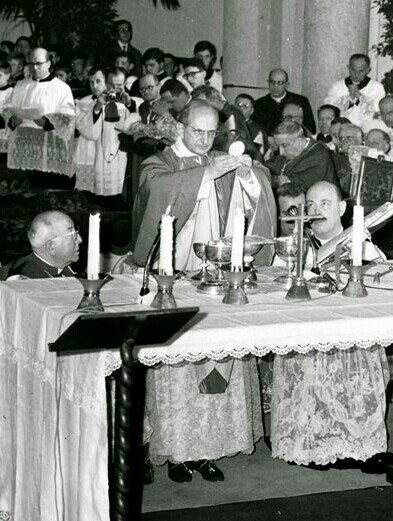

France and Italy are now closer. Not diplomatically, and it’s not conclusive proof of continental drift, but the time to travel between them has shrunk thanks to the opening of a tunnel underneath Mont Blanc. The two countries agreed on building the tunnel in 1949, but excavation didn’t begin until a full decade later, with a company from each country drilling from their own side. The excavations met on August 4th, 1962, with an axis variation of a mere 5 inches. The tunnel was inaugurated at a ceremony on July 16th, attended by French President Charles de Gaulle and Italian President Giuseppe Saragat, and opened to traffic three days later.

At 8,140 feet below the surface, the two-lane highway tunnel is the deepest operational tunnel in the world, and at 7.2 miles, it is also the longest highway tunnel, some three times longer than the previous record holder, the Honshu-Kyushu tunnel in Japan. The travel distance from France to Turin is now 30 miles shorter, and the distance to Milan is 60 miles shorter.

Presidents de Gaulle and Saragat in front of the Mont Blanc tunnel connecting Chamonix to Courmayeur during the official inauguration

Flash!

Kodak made a big splash when they introduced the Instamatic camera two years ago. Like the venerable Brownie, the Instamatic makes it easy for amateurs to take snapshots. There’s even a model with a built-in flashgun that takes so-called peanut bulbs. The problem with those is that bulbs have to be removed before you can take another shot with the flash, and they get very, very hot. Kodak, working together with Sylvania Electronics, has come up with a solution: the flashcube.

As the name suggests, it’s a cube with a mount that connects to the camera on the bottom, and four flashbulbs around the sides. Trigger the shutter, the flash goes off, the cube rotates 90° and it’s ready for another picture immediately. Plus, by the time you’ve taken the fourth picture, parts of the cube should be cool enough to touch, so you can replace it right away. This should mean lots more candid snaps and a lot less dragging everybody outside to squint into the sun at family gatherings. A big innovation in a very small package.

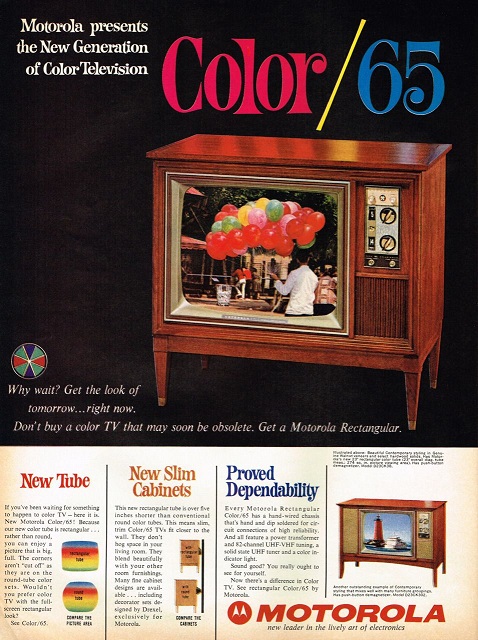

$100 is a little pricey, but there are less expensive models, and we are talking about a lifetime of memories

An electrifying performance

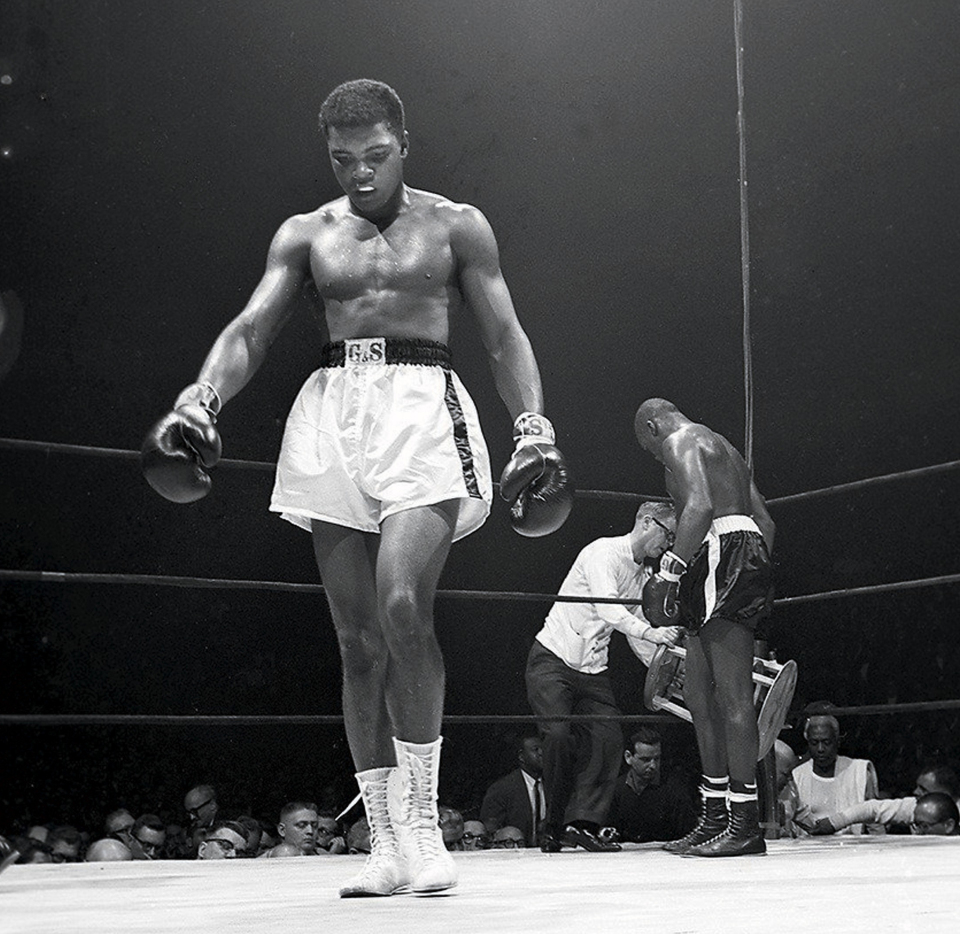

The folk world had their horizons expanded last week, perhaps to their dismay. Despite his bad boy antics off stage last year, Bob Dylan was the most eagerly anticipated act at this year’s Newport Folk Festival, but his performance was met with a chorus of boos. It seems young Mr. Dylan felt that Alan Lomax was rather condescending when introducing the Paul Butterfield Blues Band at a workshop on Saturday the 24th and decided he would play electric to prove to the organizers they couldn’t keep it out. He hastily assembled a band from a couple of members of the Butterfield Band and some others and spent Sunday afternoon rehearsing. The crowd was shocked at the sight of Dylan accompanied by an electric band, and the short set of “Maggie’s Farm”, “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Phantom Engineer” was met with both boos and cheers. MC Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul and Mary) dragged Dylan out for a quick acoustic encore of “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”. The crowd exploded and begged for another encore.

So why the booing? Ask three different people and you’ll get four different answers. Some say it was folkies mortally offended at the mere presence of electric instruments or a rock sound, others that fans were upset at the shortness of the set and the fact that the band used most of their allotted 15 minutes for tuning and switching instruments and/or poor sound quality. Some will tell you it was definitely the fans booing, others blame the press or even the organizers. We may never know the truth of the matter, but there’s no question that Bob Dylan has made another big impact on music.

Dylan with electric guitar and harmonica. Completely different from his usual acoustic guitar and harmonica. (Band not shown)

Dylan with electric guitar and harmonica. Completely different from his usual acoustic guitar and harmonica. (Band not shown)

The Mysterious Doctor X

If you drop by your local library and take a look at the Sunday New York Times for July 25th (assuming they carry it and it has already come in) and flip to the list of best sellers, you’ll see a new title, Intern by Doctor X. It is, by all reports, a rather harrowing account of a young doctor’s period of interning at a hospital a few years ago, taken from his daily journal. The names, as Jack Webb would say, have been changed to protect the innocent, and the doctor has chosen a pseudonym to further protect confidentiality. “What has that got to do with science fiction,” you ask. Well, a little bird told me that Doctor X is in fact a reasonably well-known science fiction writer. Since he has good reasons for concealing his identity, I won’t give it away, but I will say that I once thought he was a pseudonym for Andre Norton and that his last name closely resembles a different medical profession mostly practiced by women.

Another hint: It’s not Murray Leinster or James White

Another hint: It’s not Murray Leinster or James White

It’s bigger, but is it better?

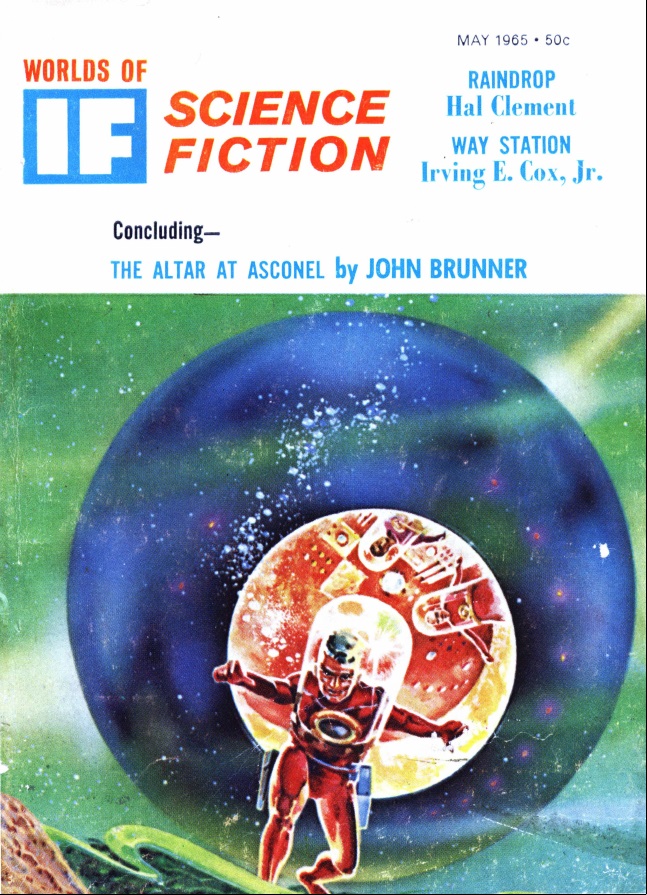

As promised last month, IF is now 32 pages longer, making it the same size as its bi-monthly sister publication Worlds of Tomorrow. Fred Pohl claimed that’s enough for two more novelettes, four or five short stories, a complete short novel, or an extra serial installment. How well did the editorial team make use of that extra room this month? Let’s take a look.

A deadly duel begins. Art by McKenna

Continue reading [August 2, 1965] Expansion and Contraction (September 1965 IF) →

![[January 4, 1966] Keep Watching the Skies (February 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/IF-Cover-1966-02-652x372.jpg)

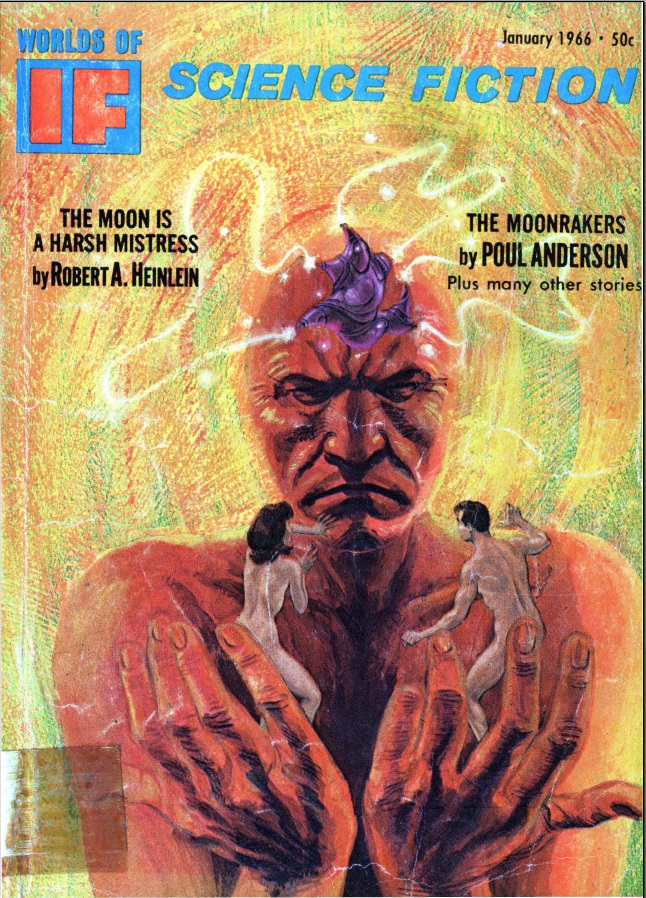

![[December 2, 1965] Superiority Complex (January 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IF-1966-01-Cover-646x372.jpg)

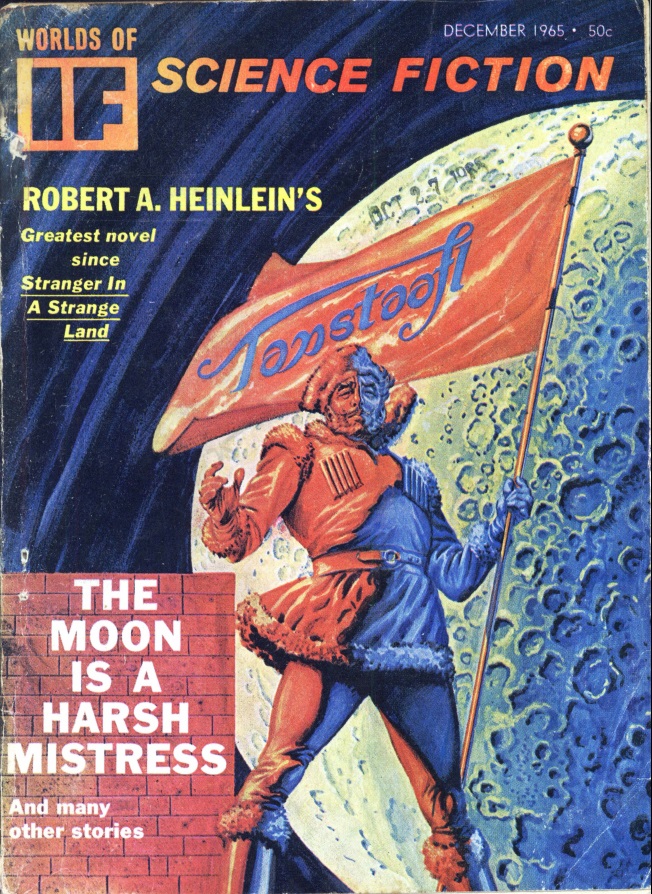

![[November 2, 1965] Revolution! (December 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IF-1965-12-Cover-652x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1965] Gimmickry (November 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/1965-11-IF-cover-645x372.jpg)

![[September 6, 1965] War and Peace (October 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IF-1965-10-cover-657x372.jpg)

![[August 2, 1965] Expansion and Contraction (September 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/IF-1965-09-Cover-654x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1965] Gallimaufry (August 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IF-cover-1965-08-649x372.jpg)

![[June 2, 1965] Heck in a Handbasket (July 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/1965-07-IF-cover-653x372.jpg)

![[May 2, 1965] FORWARD INTO THE PAST (June 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/IF-June-1965-cover-647x372.jpg)

![[April 2, 1965] SPEAKING A COMMON LANGUAGE (May 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IF-April-cover-647x372.jpg)