by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

This month I am trying to be more optimistic about the British magazines. Now that the sun is out, why wouldn’t I be? But to be honest, the last couple of issues have rather underwhelmed on the whole. That’s not to say that there haven’t been great moments but much of the material has seemed – well, predictable.

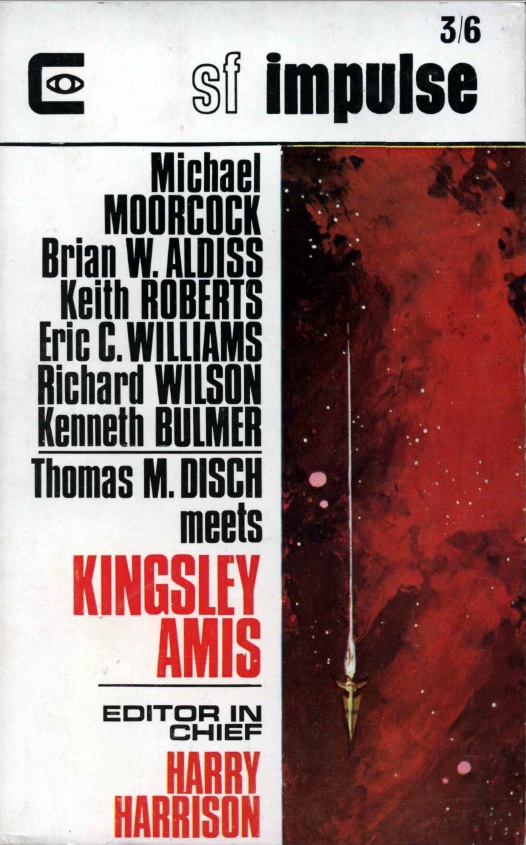

To Impulse first.

An interesting cover this month, with polymath and Associate Editor Mr. Keith Roberts illustrating the last part of his Pavane series. Where does he find the time?

After a month off, Kyril’s Editorial this month continues his recent ruminating that he doesn’t know what to write about as an Editor. It’s a sadly oft-repeated theme, and makes me think that Kyril really has lost interest in the job. The only thing of note here is that Harry Harrison’s latest novel, Make Room! Make Room! (recently reviewed by my colleague Jason HERE for Galactic Journey) will appear here from next month, which I am looking forward to.

Of more interest, the Editorial is followed by an essay by the “Guest Editorial” writer from last month, Harry Harrison. With that in mind, it shouldn’t be too surprising that the “Critique” (as it is called) rather reads as if it should be the Editorial rather than an essay. It is the first of a regular monthly essay, in which (as Kyril puts it) “…untrammelled by fear or favour, he will praise the best, trounce the worst, review current science / fantasy / fiction and cope with any reader’s letter which strikes a spark in his great soul.”

In other words, Harry is doing what an editor should do. As to be expected, the article, once again, makes good points about the state of British sf and the need to grow up, but it is nothing new. I like the fact that Harry has asked for definitions of sf, with the winner being offered a year’s free subscription. (This, of course, assumes that Impulse will last for at least a year!)

Let’s move on. To this month’s actual stories.

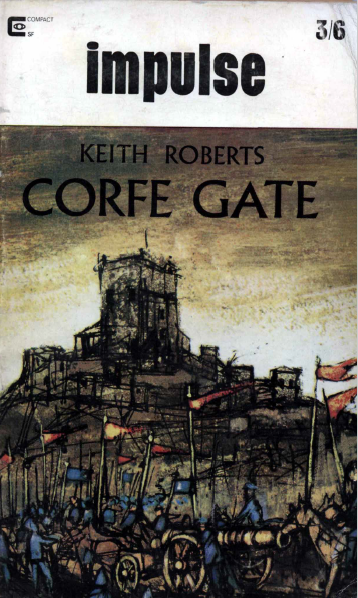

Pavane: Corfe Gate, by Keith Roberts

The fifth story from Roberts’ alternate History takes us back to a place we visited last month – Corfe Castle, which last time was the home of Robert, Lord of Purbeck and where Robert took Anne Strange. This time the hints of change made before, suggesting that we may be on the way to revolution, seem to have come true.

Several decades in the future, Corfe Gate continues this story of rebellion and change by telling the story of Lady Eleanor, who refuses to pay the tithe demanded by the Roman Catholic Church because the people of Corfe Castle would starve in order to do so. As King Charles is away in the New World, this leads to Lord Henry of Rye and Deal turning up on her doorstop ready to fight on behalf of Pope John of Rome. Eleanor refuses to yield, believing that King Charles would never allow his people to suffer. The revolution spreads, until King Charles arrives at Corfe Castle and the matter is resolved.

Around this story, much of the narrative tells us about Eleanor’s life and how she got to this point.

As the final part of this series, this is where the different elements seen so far come together. Corfe Gate is really the story of Eleanor, the daughter of Robert and Anne Strange, who were in the last story. In Corfe Gate we see the power wielded by Parliament and the Roman Catholic Church, of whom we found out about in the second story, with the semaphore system of the Royal Signallers who we found out about in the first story also playing a part. We even have the brief return of the Lady Anne, the steam tractor of the second part.

But most of all we read of a young woman in a patriarchal world determined to do their best for her people, against the forces of conservatism and inertia equally determined to crush her rebellion before it becomes something bigger.

It is a story where we are undoubtedly meant to feel for Eleanor, and it is to the writer’s credit that I did. Corfe Gate is a powerful story that caps the series wonderfully. 4 out of 5.

The OH in Jose by Brian W Aldiss

Once again, where Harry Harrison goes, Brian Aldiss follows – not the first time the two have appeared in the same issue of New Worlds or Impulse/Science Fantasy. Can we be sure they are not the same person? Nevertheless, the story is a typical piece of Aldiss whimsy – that is to say, on the mildly humorous side but with a point to make.

A number of travellers make up wildly different stories about the origin of the word “Jose” carved into a rock, before the truth is revealed. A much-needed lighter story after the darkness of Roberts’s Pavane. Another that has already been published, however. 3 out of 5.

The White Monument by Peter Redgrove

A new author. This one is subtitled “A Monologue” and is the tale of a man who, annoyed by the sound coming from his house’s chimney, creates a monument for his wife who is entombed by his efforts to fill the noisy chimney with concrete. Lyrical and experimental yet as silly as it sounds. Another story that has appeared elsewhere before – this time as a radio play on the BBC’s Light Programme. 2 out of 5.

The Beautiful Man, by Robert Clough

Another new author. Three goatherders discover skeletons in a cave, and a crucifix. A twist in the tale story that suggests that this is a post-apocalyptic world. Pretty predictable. 3 out of 5.

Pattern As Set by John Rankine

The return of an author last seen in the May 1966 issue, with the rather underwhelming story of The Seventh Moon. This time I was slightly more impressed – perhaps the shorter length plays more to John’s strengths. Mark Bowden is a pilot on the Cyborax, a spaceship on a hundred-years-long journey, where one at a time members of the crew are unfrozen to do their duty. Borden spends most of the beginning of the story lusting after teammate Dena. The story becomes more interesting when Bowden tries to defrost the next crew member to find that they have died. The end is a disappointment, in the manner of “so…it was all a dream!” 3 out of 5.

A Hot Summer’s Day by John Bell

What's this? A story about Summer, published in Summer? We’ll be getting Christmas stories in December next!

A new author, but this is a satisfactory enough tale of a day in a future London, where getting to work via private or public transport is a significant challenge. It begins with descriptions where traffic is at a standstill, riots on the London Underground are common, people are invariably late for work and the resulting stress levels make London a miserable place to be. As if this wasn’t enough, the story then piles on descriptions of overcrowded sweatiness and grumpy employers, to the point where the story ends with parts of London being razed to the ground by rioters. Seems a little extreme, but rather inevitable as the story ramps things up to its ending. It was fun to read of Tube stations being places of chaos and disorder. One for the commuters, I guess. 3 out of 5.

The Report by Russell Parker

Another new author, but a story of little consequence. Written in the form of a report, it tells of a post war world where thirteen months ago nations released nuclear weapons on each other and wiped out most cities. So far, so predictable.

The point of the story seems to be that the war seems to have started by accident – not with an attack on cities like London (if there’s any of London left after the previous story, of course!) but with a meteor strike on Norfolk! (For non-British readers, Norfolk is an area of flat, mainly rural countryside which I’m tempted to describe as a British equivalent of the Florida Everglades, if cooler.) 3 out of 5.

Hurry Down Sunshine by Roger Jones

By contrast to the chaos of A Hot Summer’s Day, Hurry Down Sunshine is a story of a supremely organised future, from another new author. In this future, the clinically clean world feels deliberately Kafka-esque, and is not helped by the point that the efficient government is run from the sidelines by the rather Dr. Strangelove-like Dr. Holzhacker, who sacrifices everything in the name of efficiency.

Towards these ends, in order to reduce mental instability in a country free of crime, Smith is promoted from anonymous office drone to be the nation’s scapegoat (an Official National Criminal), upon whom all grievances can be laid. Said scapegoat is placed on the much-maligned and mostly unused national railways, the last in existence in the world. In this manner, Smith not only fulfills his duty in comparative safety (for no one rides the train to vent their frustrations on the scapegoat) and the railways get an extra lease on life — after all, they can't be shut down while they have such an important customer on board. Our randomly selected stooge rides the rails for eighteen months, during which a Report is produced which includes Smith’s unpublished letters to The Times newspaper. This becomes a bestseller. As Smith pulls into a station, a mob of angry citizens arrived determined to make Smith pay for his ‘crimes’. But they assail the wrong train, and Smith, rather hurt at not being able to fulfill his scapegoat duty, is whisked to Bletchley.

Subdivided into sections like a J. G. Ballard story, this is another satire, like Ernest Hill’s story Sub-liminal in last month’s New Worlds – but better. It is good fun, although still rather silly. 3 out of 5.

Summing up Impulse

Well, I’m pleased to type that I generally enjoyed this one – more than last month’s anyway. Admittedly, it’s not perfect. Whilst I’m pleased to see new writers given their moment in the sun alongside the big-hitters, some of the material (again) shows inexperience and banality or even extreme and bizarre mood changes. They lack the subtlety of quality writing, although they are good efforts overall. With the exception of Corfe Gate, there’s nothing really memorable here, although they’re all entertaining enough.

And with that, onto issue 164 of New Worlds, hoping that it is better.

The Second Issue At Hand

Like last month’s Impulse, the Editorial in New Worlds is a Guest Editorial. Instead of Moorcock this month, we get his friend J. G. Ballard making another appearance. (Is it Editor’s Holiday time, I wonder? What is going on?)

Ballard being Ballard, this is not an Editorial as such but a review of a film – La Jetee, directed by Chris Marker. (Why this couldn’t be later in the issue as a review, rather than as the Editorial is a mystery.) Anyway, Ballard loved it – unsurprisingly, as it appears to be a film tailored to Ballard’s own interests. It is entirely made up of black-and-white photographs but put on film. The film is bold and experimental – and even has an sf theme.

Might be worth a look, but not for everyone – rather like Ballard's own writing!

To the stories!

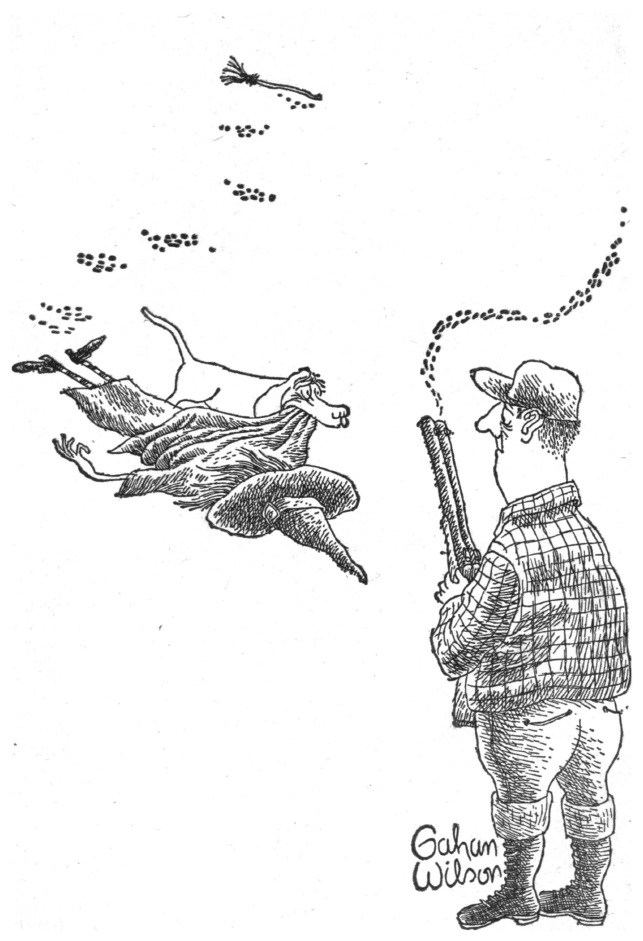

Illustration by James Cawthorn

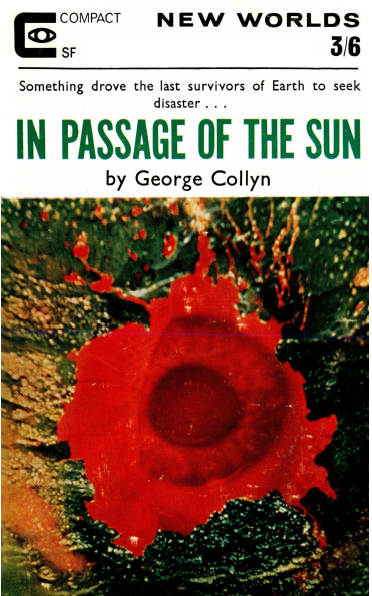

In Passage of the Sun, by George Collyn

George is a regular contributor to the magazines, both as a writer and as a critic/reviewer. This has an intriguing first line – “You can have no idea of what it was like in those last days of Earth.” – before settling into post-apocalyptic Space Opera shenanigans. Our ‘hero’ is taken from the overcrowded domes of Earth in the ongoing war between humans and the lizard-like Throngians, and is then put into a war not only between the humans and the Throngians but also a political battle between the King and other factions.

In some ways In Passage Of The Sun was old-school, old style Space Opera, in that it is really old ideas rehashed into something not terribly new.

The main difference I guess is where an old story of this type would try to show Humanity succeeding against all the odds, this one suggests little but backstabbing, meaningless slaughter and misery. The first part of the story seems to revel in grime, sweat and dead bodies – a typically British dystopian story! It did get a little better after that, but as the lead story of an issue, it is wildly uneven. I felt that it really wasn’t cover story material.

Which rather makes me worry about the quality of the rest of the issue. Are we scraping the barrel a bit, here?

A low 3 out of 5.

The Other, by Katherine Maclean

The return of an author who has had stories steadily published from the 1950’s. The Other is the story of Joey, who we discover is an artificially constructed being, and “The Other”, a voice inside Joey’s head. After a psychiatric meeting with Doctor Armstrong and Joey we find that The Other may be more than we at first expected. As expected from a veteran writer, the story is short but memorable, even if it feels like only part of a bigger story. It’s not Maclean’s best but it stands out in this issue. 4 out of 5.

Sanitarium, by Jon DeCles

A newcomer to me, though I understand he has been published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction before. A strange story about a strange future, where even sexual satisfaction is provided by the State. It is mainly about people in the Sanitarium, who are generally unpleasant. Nearly three-hundred-year-old Romf Brigham is invited by his strange neighbours to a party to celebrate Mrs. Christopher Carson’s absence for six months and becomes involved in the investigation. The story loses momentum though as we are told from the start where she is. An attempt at satire in a decadent future, which seems to celebrate decadent excess and languor. I found it pretty unpleasant. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The Way to London Town, by David Redd

Nancy arrives in Sacaradown, observes the people there and meets Walther, who collects “strange people”, who Nancy seems to be. He becomes obsessed with finding out more about eleven-year-old Nancy, and Nancy says that she wants to collect enough money to visit places earlier in time, like London before the war that destroyed it. It’s a clumsy plot device to allow the writer to fill in background. We discover that Nancy is a mutant who can travel through time at will.

I suspect that this will be the first of a series, rather like Keith Roberts’ Anita was. This shares some similarities to those stories – an unusual outsider, seemingly innocent, for example. But whereas Anita was often charming, in places this unsubtle story comes across as creepy and odd. It gets better towards the end, but by then the damage is done. 2 out of 5.

The Outcasts, by Kris Neville

One of those lyrical, allegorical stories that Moorcock loves. This one is about a Los Angeles, full of pushers and strange women. No real story to it, the writer seems to be more interested in writing interesting prose and create vivid imagery rather than have the narrative go somewhere. Not for me, I’m afraid. 2 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The God Killers (Part 2 of 2) by John Baxter

I said last month that I thought that John Baxter’s story was too provocatively titled, but that I enjoyed it. I was even more interested to read further when last month’s New Worlds heralded this part of John Baxter’s story as “bizarre”.

A quick reminder – we were told last issue of the planet of Merryland, where the people actively worship Satanism. Young David Bonython finds in his farm’s attic forbidden technology – a matter transmitter from a heretic age whose storage threatens death or torture for David, his friends and family.

Through this arrived Hemskir, a rogue Proctor wanted for offences against Federal law.

The story finished last time with David spending the night with his stepsister Samantha Padgett at some kind of Christian ritualistic orgy. When David returned to the Padgett farm the next day, he found Hemskir dead and the farm on fire.

The farm has been set ablaze by the Examiners, the local justice force who have been tipped off by Elton Penn, the leader of the Christian group. David rescues Samantha at the farm, who goes with him, albeit reluctantly, to the city of New Harbour. There they are captured by Penn, but escape. David realises that Penn is searching for the place of origin of the green crystal that is so rare, but by looking at a map he and Samantha, now lovers, sail to a research station where they find a lake of the stuff. The green crystal is malleable to their will – basically if they can think it, the crystal will turn into it – solid, liquid or gas. Penn has followed them there in a spaceship and there is the inevitable showdown.

There’s some nice descriptions of the world in decay here and some nice ideas of ancient forbidden technology that I liked, but to counterbalance this there’s also some honking howlers in prose – try “She began to cry, savagely, as if forcing grief out of her like vomit”, or even “Love and the water turned them into beautiful animals…” All in all, despite the attempts to make it worth my reading, The Godkillers is not very surprising if you’ve read Ballard’s Crystal World, nor actually very good. Disappointing. A low 3 out of 5.

The Failure of Andrew Messiter, by Robert Cheetham

Cheetham’s first story here since A Mind of My Own in December 1965. It’s another fairly predictable story of scientific experiments in inner space. Dr. Messiter and his team of Wendy Lardner and Bill Maine conduct an experiment where, in order to prove that paranormal powers such as telekinesis exist, Messiter agrees to become what is basically a brain in a body, not connected to any of the traditional five senses. This is so that the latent powers without the usual senses working can then be goaded into action and show themselves.

Over the next year, whilst love blooms between Lardner and Maine, there are no signs of life in Messiter. Maine decides to do what he and Messiter agreed they would do if there was no activity and injects a poison into the body, leaving the couple to go and pursue their affair further. The twist in the story is that Messiter is alive and aware and only just beginning to show the means of contact they wanted before he dies. It’s readable, but not without flaws, such as the awfully awkward romance. 3 out of 5.

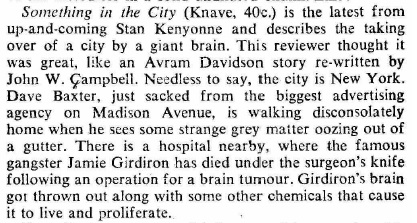

Book Reviews

A lot of reviews again this month. As ever, the reviews are colourful and entertainin,. prompted by the proliferation of new material, anthologies and reprints. As well as his Editorial/review earlier in the issue, J.G. Ballard contributes reviews of two books, Surrealism by Patrick Waldberg and The History of Surrealist Painting by Marcel Jean. As they clearly echo some of Ballard’s own ideas in his version of sf, they are, unsurprisingly, both liked.

Equally predictably, James Colvin (aka Mike Moorcock) then positively reviews in some detail J. G. Ballard’s The Crystal World, which I’ve already mentioned this month but was also serialised here a while back.

Hilary Bailey (Mrs. Moorcock to you and me) tackles the briefer reviews, covering Harry Harrison’s Plague From Space, also recently serialised in New Worlds (she likes it more than I did), Rick Raphael’s Code Three, William Tenn’s collection Time in Advance and The Eighth Galaxy Reader, all of which get generally positively reviews. However, she finds Poul Anderson’s Three Worlds to Conquer impossible to finish and dislikes his Virgin Planet enormously.

R. M. Bennett writes an essay on satirical sf, which seems to echo my own view that it is hard to write and rarely successful. Nevertheless, there are suggestions there for the reader to try.

Bill Barclay writes of new titles by a publisher admittedly unknown to me, Ronald Whiting and Wheaton. Whilst the article can come across as little more than an advertisement, there are books mentioned there that whet my appetite, including work by James White and a A Science Fiction Anthology written to commemorate the sadly-departed Cyril Kornbluth.

We still have no Letters pages this month.

Summing up New Worlds

I’m not sure why, but this month’s issue feels slightly different than usual, in its choice of content and its general tone. Is this an attempt to be different, or is it because it feels like New Worlds has had a different hand on the helm? Whilst James Colvin has made an appearance, the magazine itself seems filled with unmemorable material or stories that are just not worth shouting about. The Collyn is rather uneven, the Maclean good but not one of her best and even the John Baxter novel ends disappointingly. Has Moorcock taken his hand off the wheel? It does feel a little bit like it.

Summing up overall

So: despite my hopes, more disappointing issues this month. Not just one but both issues rather feel like there is no one at the rudder, and that the willing but exhausted subordinates have taken much of the strain. Again, they’re not bad, but there’s little that is memorable in either issue.

A tough choice then in choosing “the best”. In the end I’ve opted for Impulse again as my favourite, simply for Roberts’s Corfe Gate which is by far the best thing I’ve read this month. However neither magazine should be showered with glory this month.

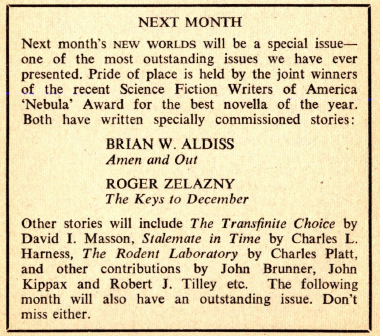

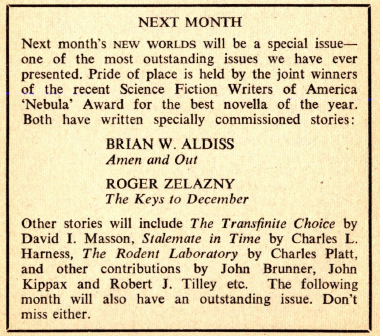

But next month's New Worlds sounds better:

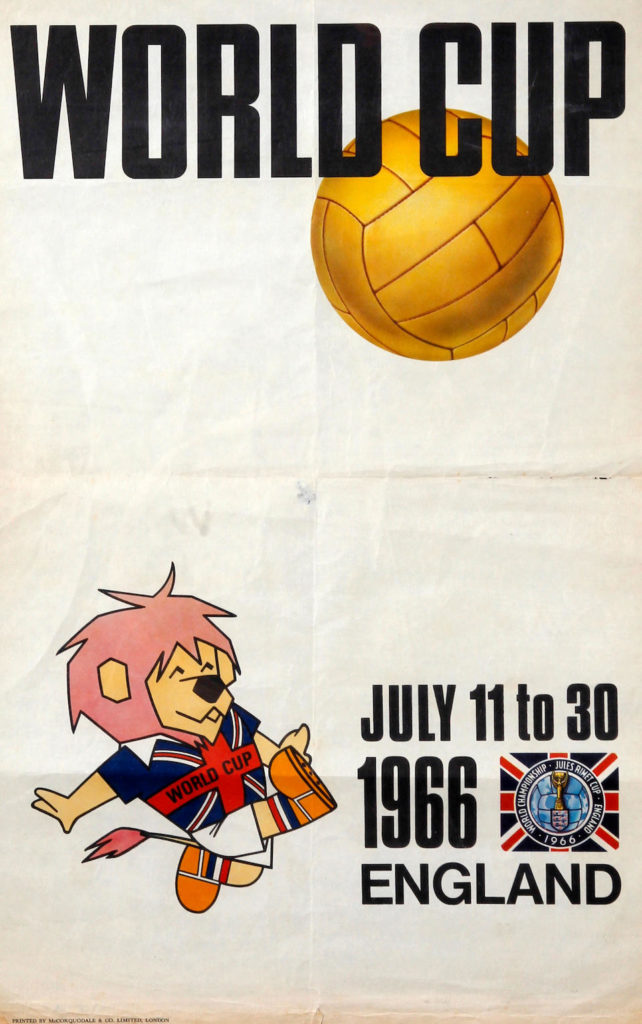

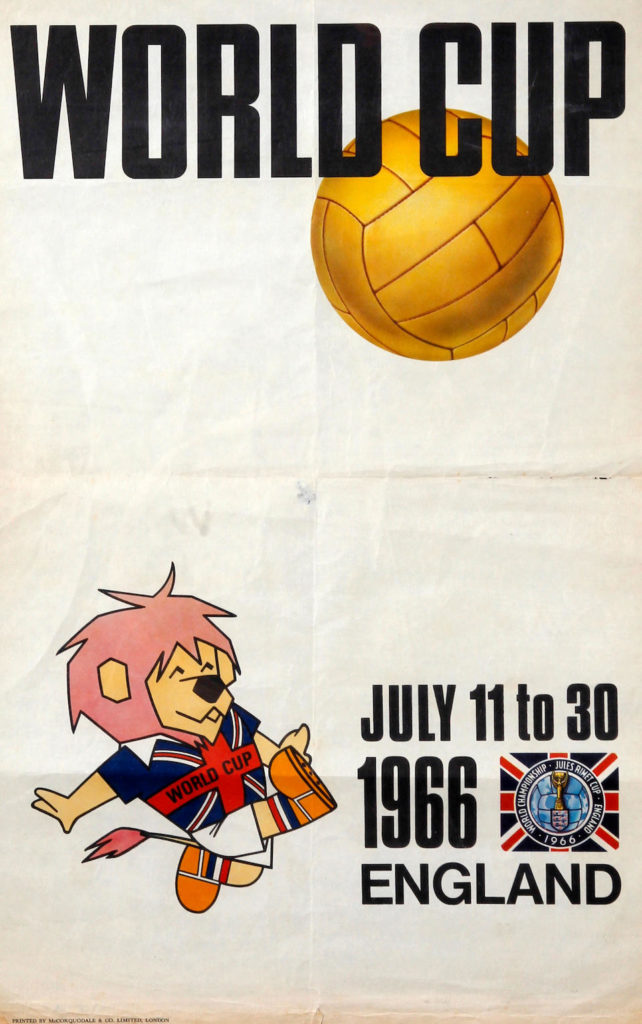

As I type this, we are about to begin a World Cup soccer tournament, with England being the host nation. Although football is not something I have much of an interest in, I feel that it would be wrong of me not to exhibit some sort of nationalistic pride on this global event. So – come on, England, etc etc.

(Moment over.)

Until the next…

![[February 24, 1970] Sex and the Single Writer: New Worlds, March 1970](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/NW-1970-3-cover-672x372.png)

![[December 24, 1969] At Last The 1980 Show: <i>New Worlds</i>, January 1970](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/NW19701-cover-672x372.png)

None of the photos I took turned out, but here's the art for the poster.

None of the photos I took turned out, but here's the art for the poster. Cover by R. Glyn Jones.

Cover by R. Glyn Jones. Illustration by Charles Platt.

Illustration by Charles Platt. Illustration by R. Glyn Jones, who gets everywhere this issue.

Illustration by R. Glyn Jones, who gets everywhere this issue. Photo by Gabi Nasemann.

Photo by Gabi Nasemann. Design by unknown artist.

Design by unknown artist. Photo by Roy Cornwall.

Photo by Roy Cornwall. Illustration by Charles Platt.

Illustration by Charles Platt. Illustration by Pam Zoline.

Illustration by Pam Zoline. Illustration by James Cawthorn.

Illustration by James Cawthorn. Photo by Roy Cornwall.

Photo by Roy Cornwall.

![[March 26, 1968] Scandal! <i>New Worlds</i>, April 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/New-Worlds-April-1968-672x372.jpg)

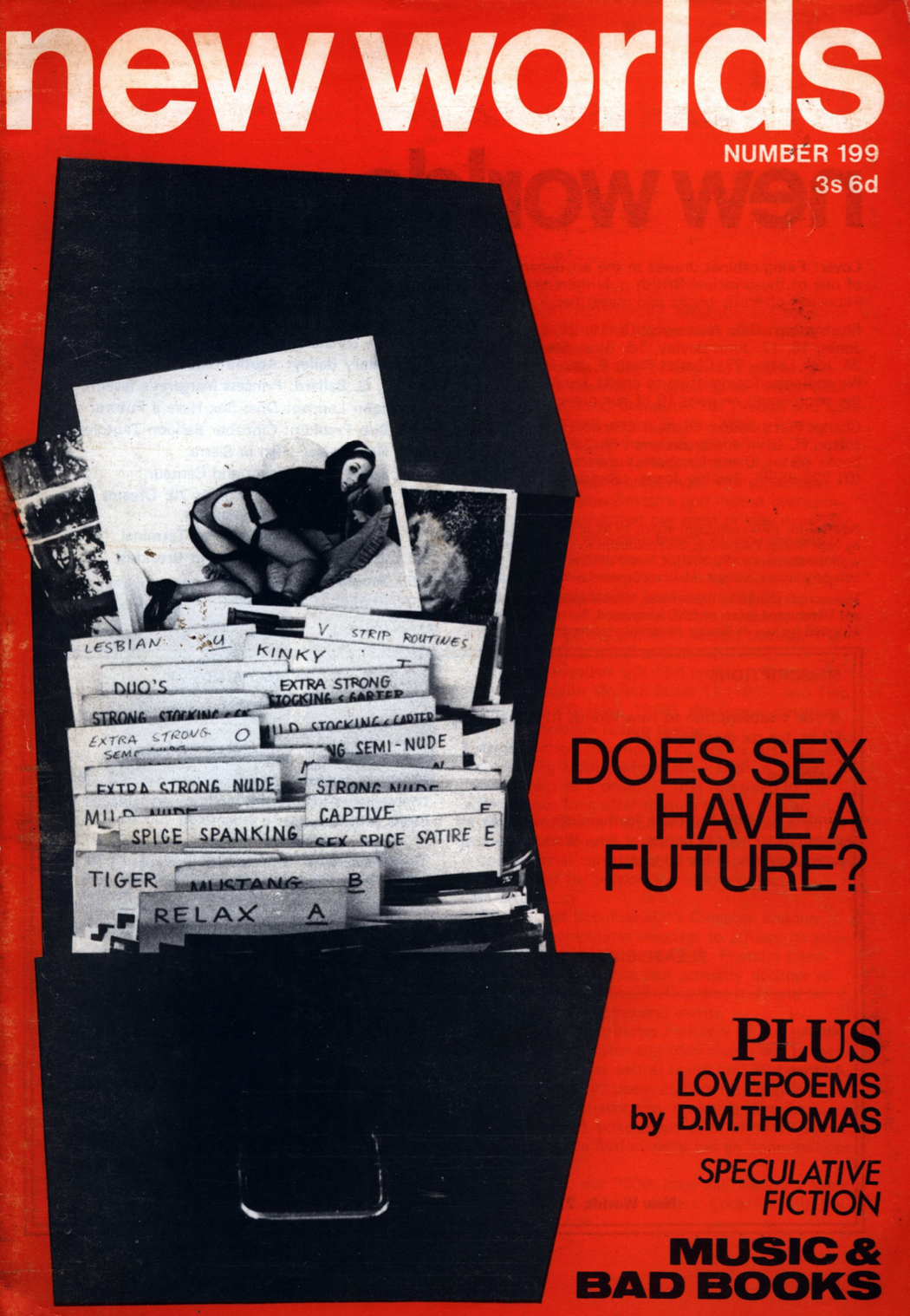

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

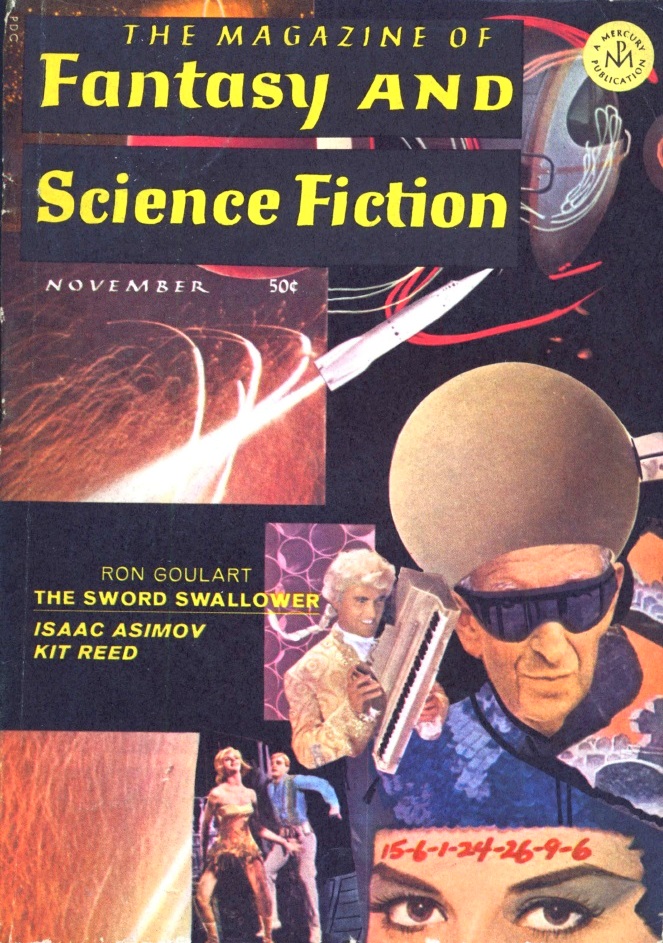

![[October 22, 1967] Equal Opportunity Employer (November 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671022cover-663x372.jpg)

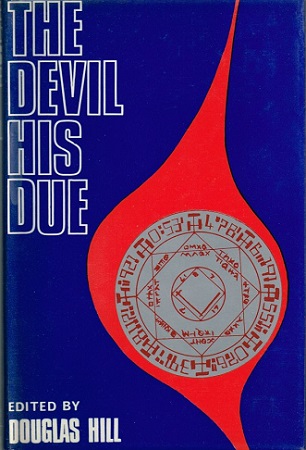

![[August 6, 1967] A Dark Future (<i>The Devil His Due</i> by Douglas Hill)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Devil-His-Due-2-306x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1966] White Boats, Whales and Disch, <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, December 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Dec-1966-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by Unknown Artist

Illustration by Unknown Artist

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[September 28, 1966] Garbage and Aliens (October 1966 <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[August 28, 1966] Messiahs and Resignation (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, September 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1966] Scapegoats, Revolution and Summer <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, July 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Impulse-NW-July-1966-672x372.png)

![[October 26, 1965] Mythology and Multiple Earths <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, November 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/nw-sf-November-1965-672x372.jpg)