by Victoria Silverwolf

Burning Curiosity

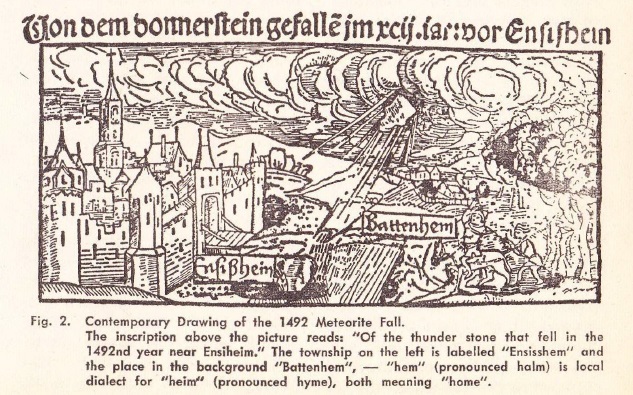

It's probably just my morbid imagination, but it seems to me that the most intriguing, if horrifying, event in recent days was the demise of Doctor John Irving Bentley earlier this month. The elderly physician was reduced to a pile of ashes (except for part of one leg) in what some people are calling a case of spontaneous human combustion.

The scene of the fire. Notice the large hole in the floor caused by the flames. I have deliberately avoided sharing more gruesome photographs.

Church Music

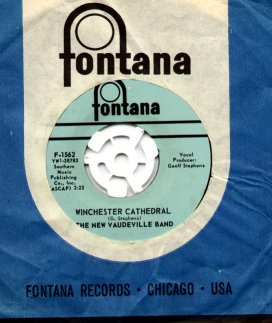

After that piece of news, it's a relief to turn to a piece of light entertainment. The unique novelty song Winchester Cathedral by some British folks calling themselves the New Vaudeville Band, currently at the top of the American music charts, is a deliberately old-fashioned number. It sounds like something Rudy Vallee might have offered in the 1920's, complete with singing through a megaphone and a finishing chorus of oh-bo-de-o-do.

Rumor has it that the song was recorded by session musicians hired for the occasion, and that the band was hastily put together when it became a hit.

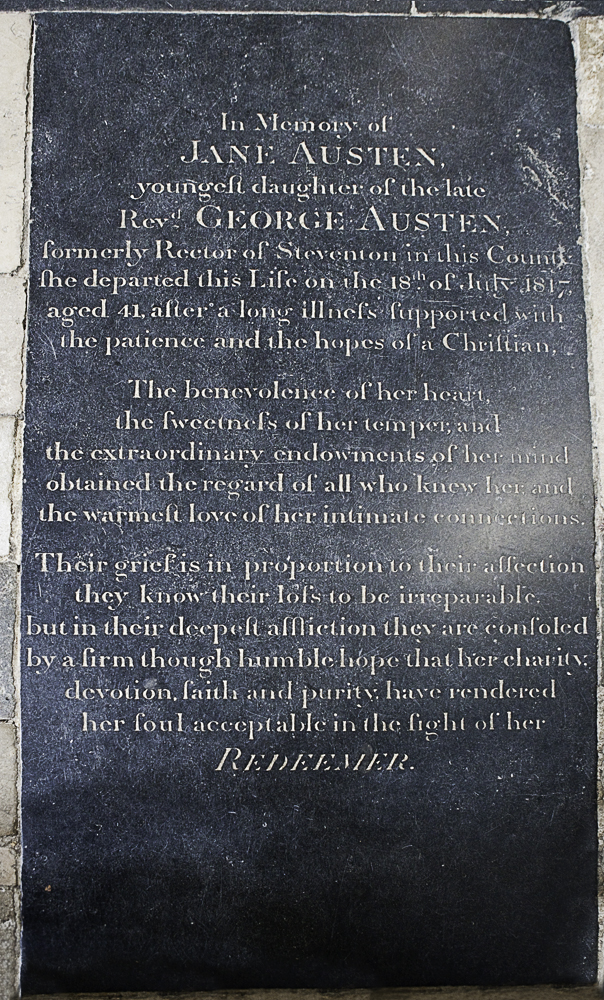

Well, that got me to thinking about all the folks buried in Winchester Cathedral. (There's that morbid imagination at work again.) The most familiar one — to me, at least — is the great author Jane Austen.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a dead woman in possession of a good reputation must be in want of a lengthy epitaph.

Gore on the Pages

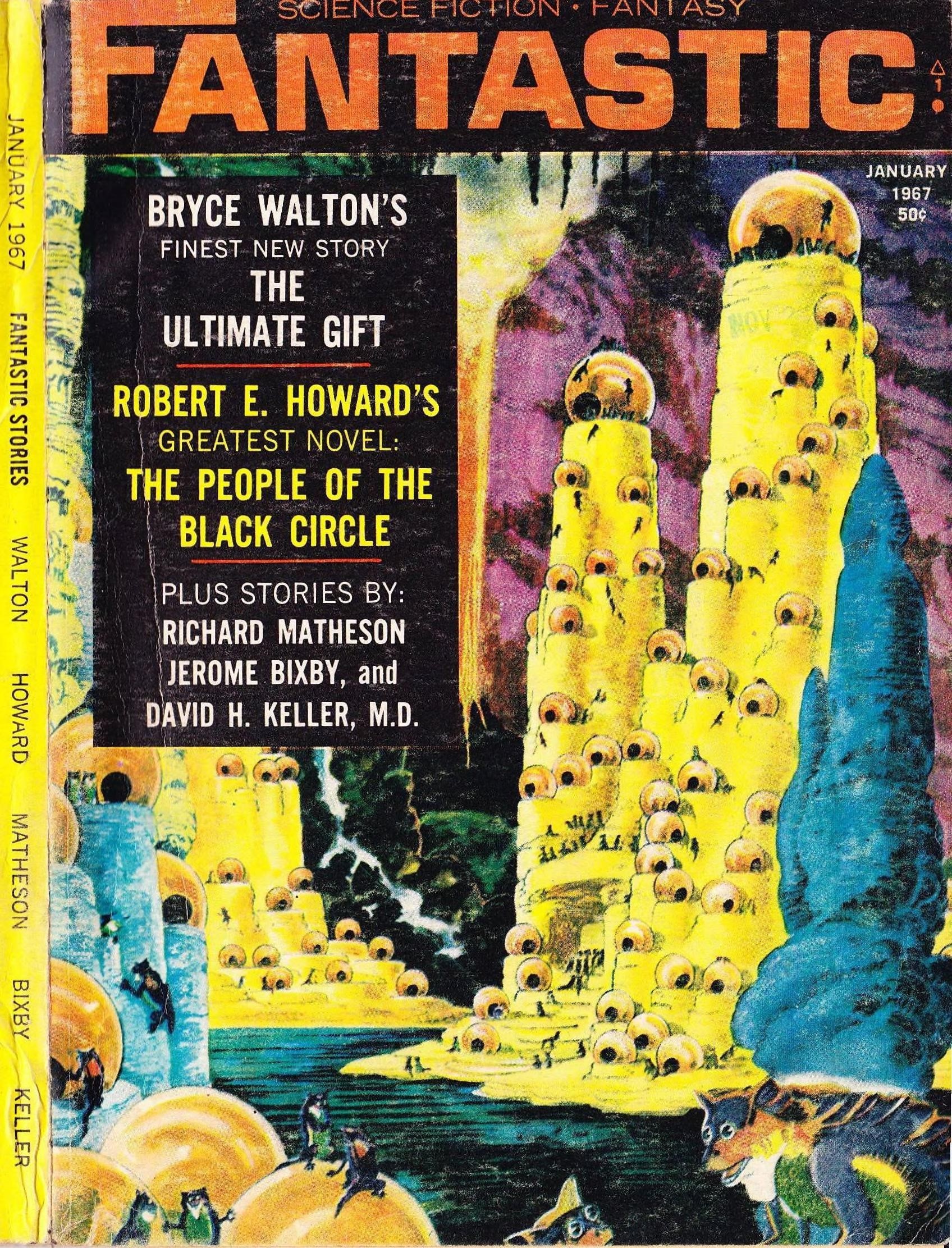

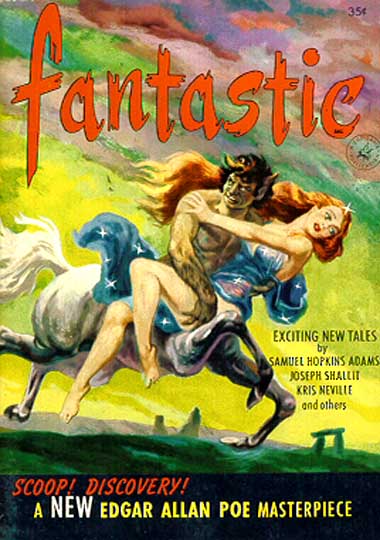

Given my grim mood, it's appropriate that the

latest issue of Fantastic is full of violence, horror, and bizarre manipulations of the human body.

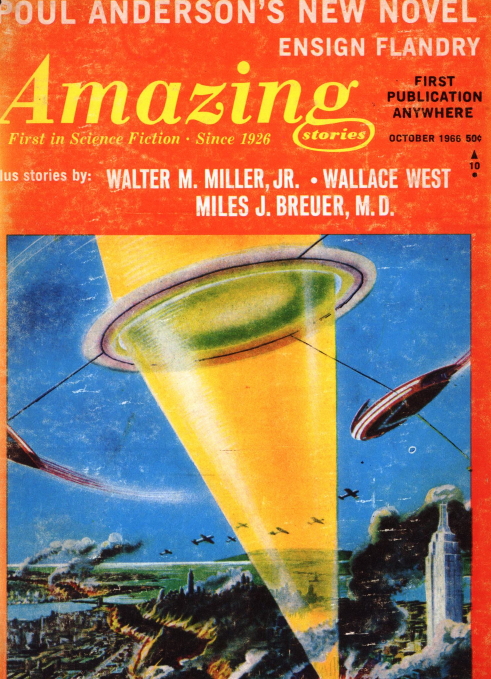

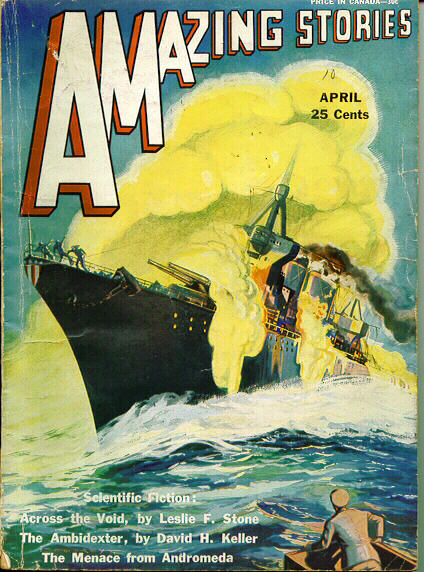

Cover art by Frank R. Paul, stolen from the back cover of the March 1941 issue of Amazing Stories.

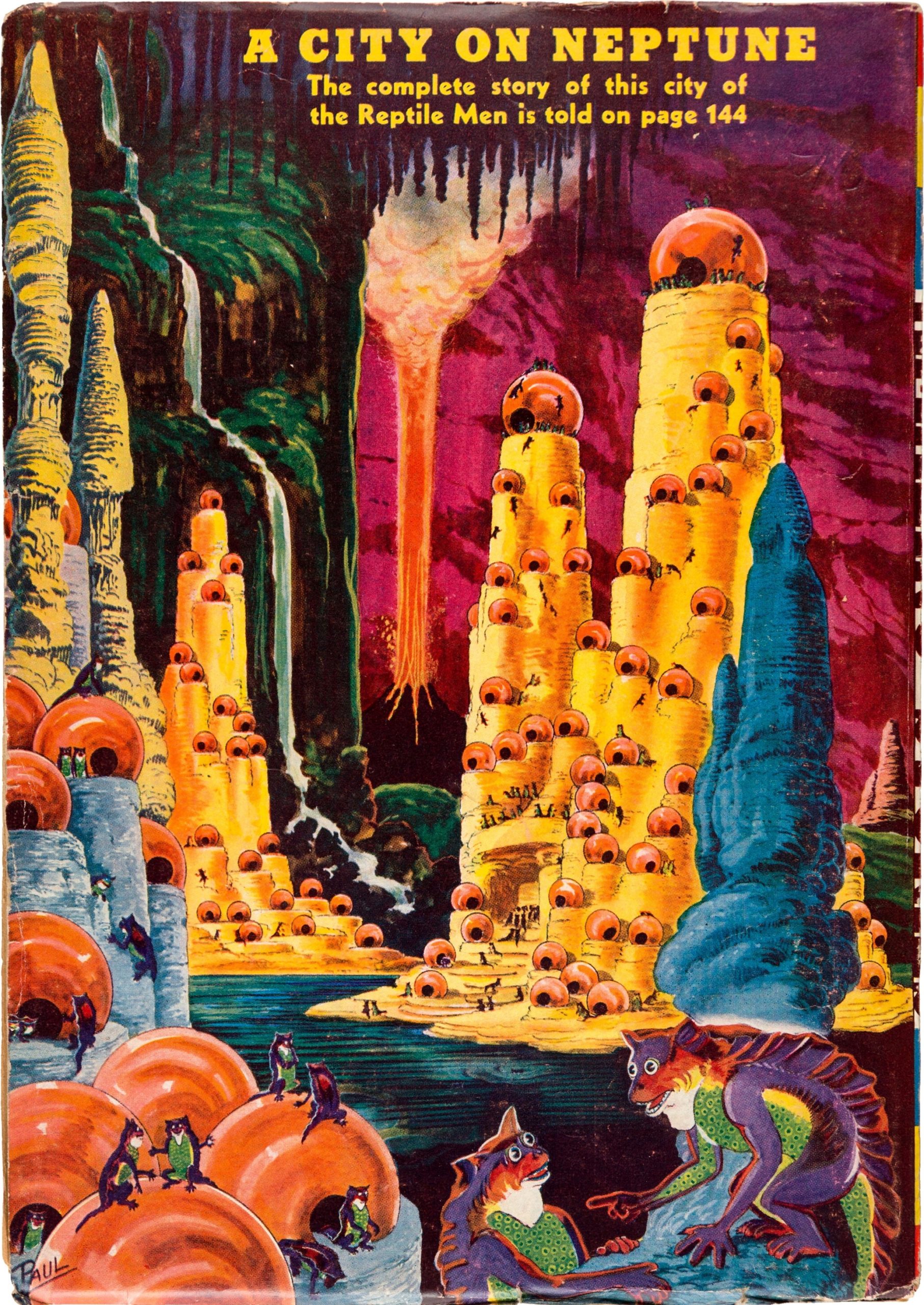

The original, with brighter colors. The Reptile Men (no women?) are cute.

The Ultimate Gift, by Bryce Walton

We begin our journey into the macabre with the magazine's only original work.

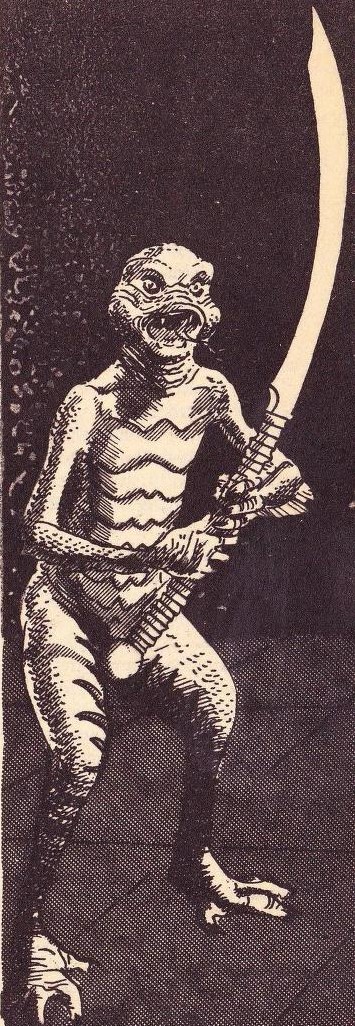

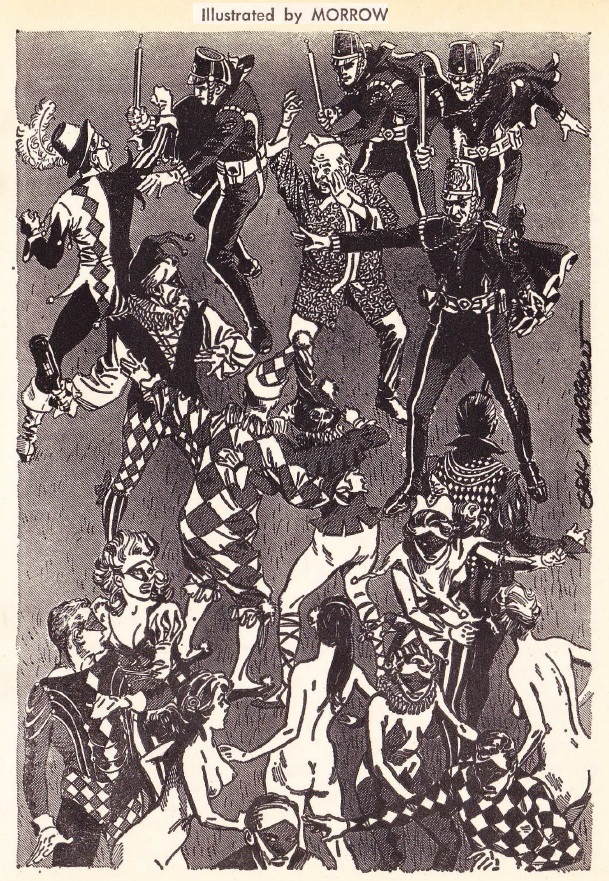

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

Aliens arrive at the Moon. They seem ready to conquer the world, but are hesitant about humanity's ability to put up a fight. They allow envoys to pay a visit, but kill them for some unknown violation of protocol. The dying words (thoughts, really, but let's not get into that subplot) of the most recent victim lead to an unusual choice for the next diplomat.

The so-called Basket Man was born without arms or legs. After years of misery, he winds up as a sideshow freak, making use of advanced technology to move around and manipulate things. In his bitterness, he refuses to have artificial limbs attached to his torso. A representative from the United Nations, based on the hint noted in the paragraph above, convinces him to acquire robotic arms and legs, and to head to the Moon to meet the aliens.

The fact that they're reptilian, sort of like the creatures on the cover, is relevant.

A little knowledge of zoology may lead you to predict the reason for the aliens' violent reaction to their visitors. As you may have guessed from my description, this is a ghastly little story, with a particularly disquieting scene near the end. It has a certain raw power, I suppose. Given the infamous thalidomide tragedy of not so many years ago, the premise may strike many readers as being in poor taste.

Two stars.

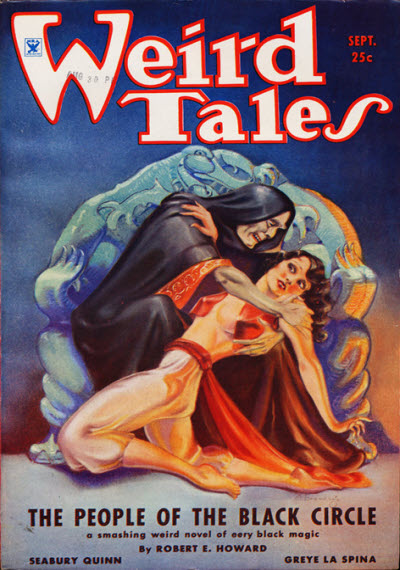

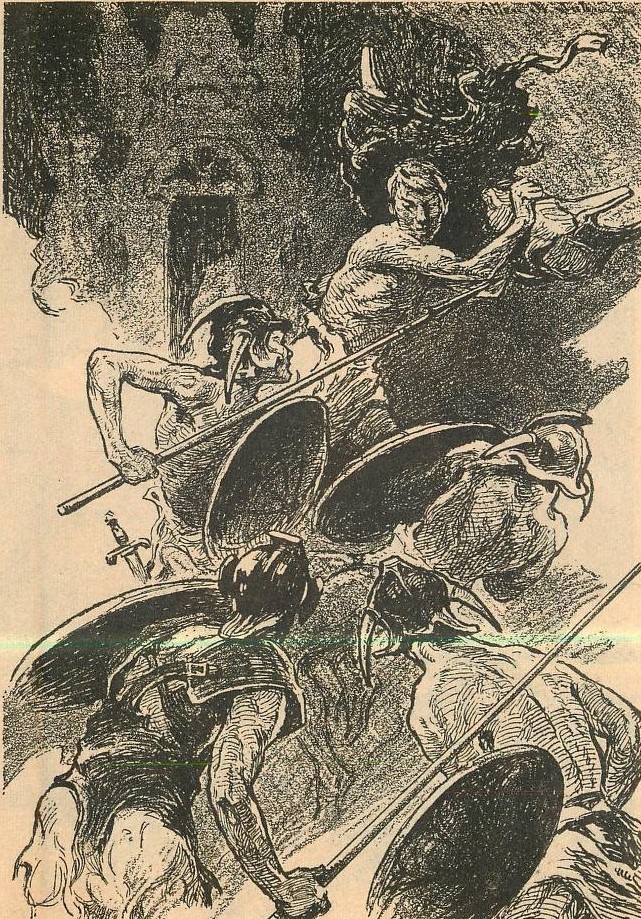

The People of the Black Circle, By Robert E. Howard

Dominating the issue is a bloody sword-and-sorcery adventure, featuring a hero who seems to be making a comeback of sorts. This novella was originally serialized in three parts, in the September, October, and November 1934 issues of Weird Tales.

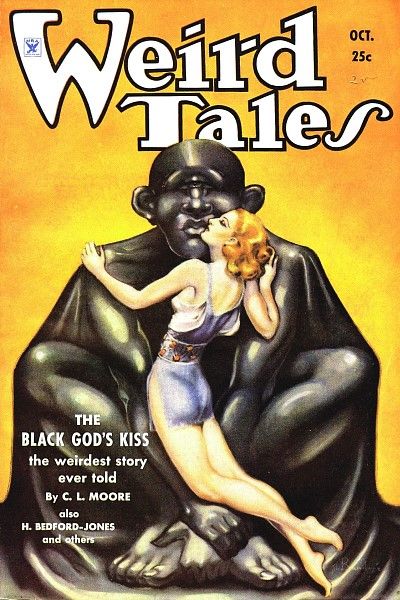

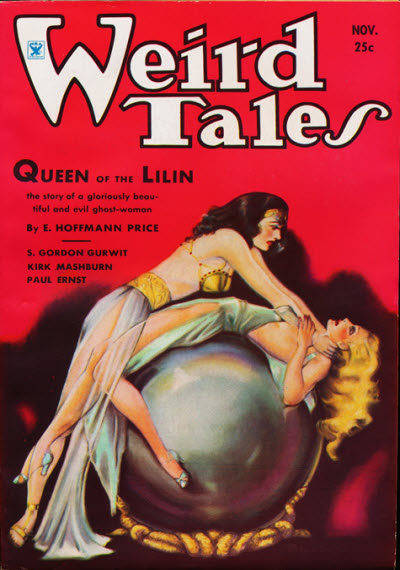

All cover art by Margaret Brundage.

Brundage often painted scantily clad young ladies for the magazine.

Two scantily clad young ladies.

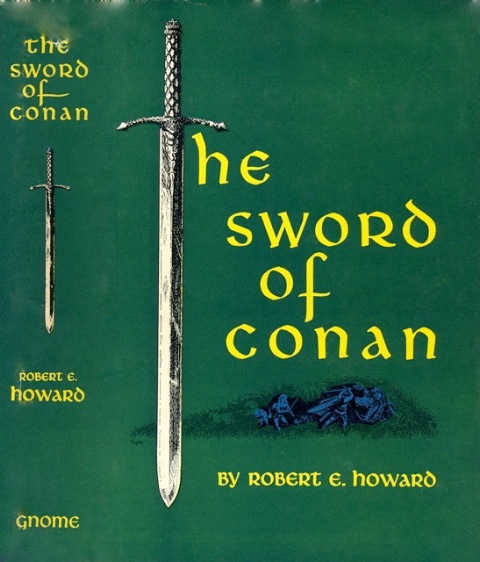

Before I get into the story itself, let me talk about the revival of interest in Robert E. Howard and his most famous creation. The tales of Conan were left in the yellowing pages of old pulp magazines until specialty publisher Gnome Press starting collecting them in several volumes.

Cover art by David A. Kyle. The novella under discussion appears in this book, number two in the Gnome Press series, from 1952.

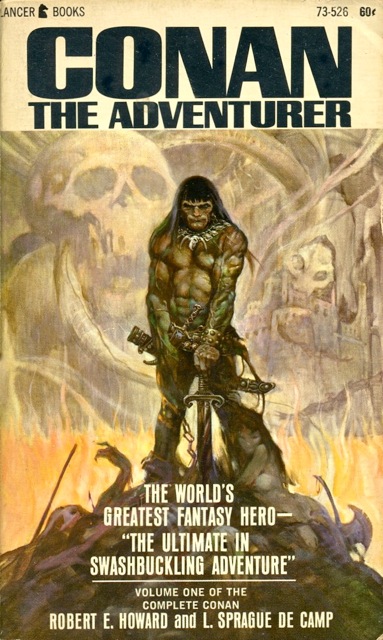

Earlier this year, the story appeared in a paperback collection. (It should be noted here that L. Sprague de Camp completed some of Howard's unfinished works about Conan.)

Cover art by Frank Frazetta.

The setting is an imaginary ancient past. There are clues that this takes place in a fantasy version of the Afghanistan/Pakistan/India region. (Some of the hints are a bit too obvious, such as a chain of mountains called the Himelians.) We begin with a king whose soul is about to be stolen by evil sorcerers. Rather than allow this to happen, he orders his sister to kill him.

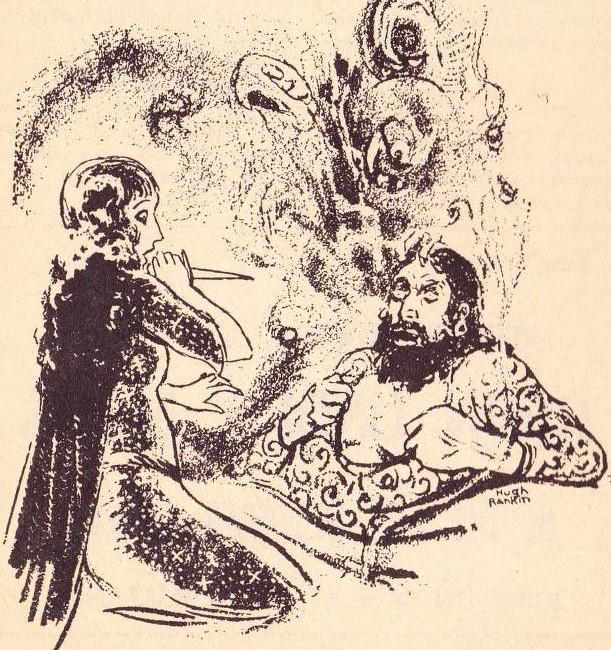

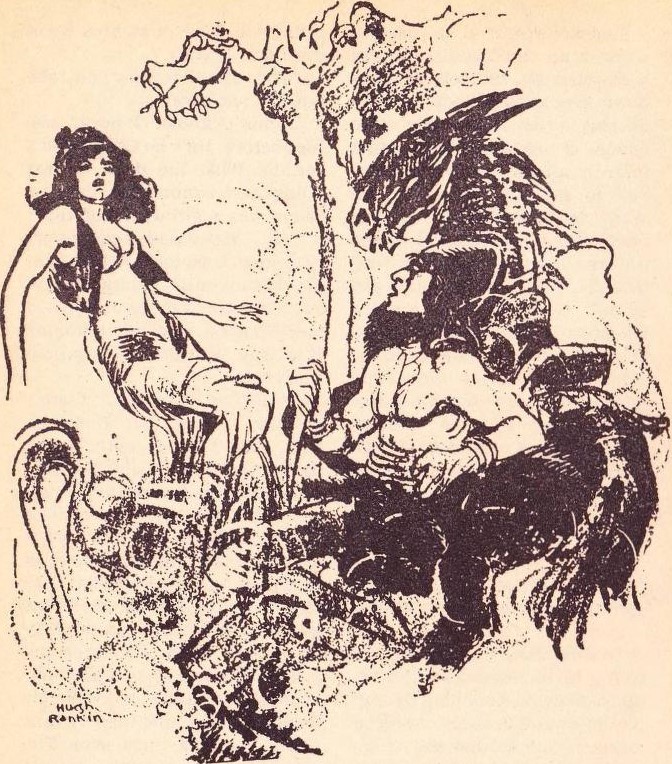

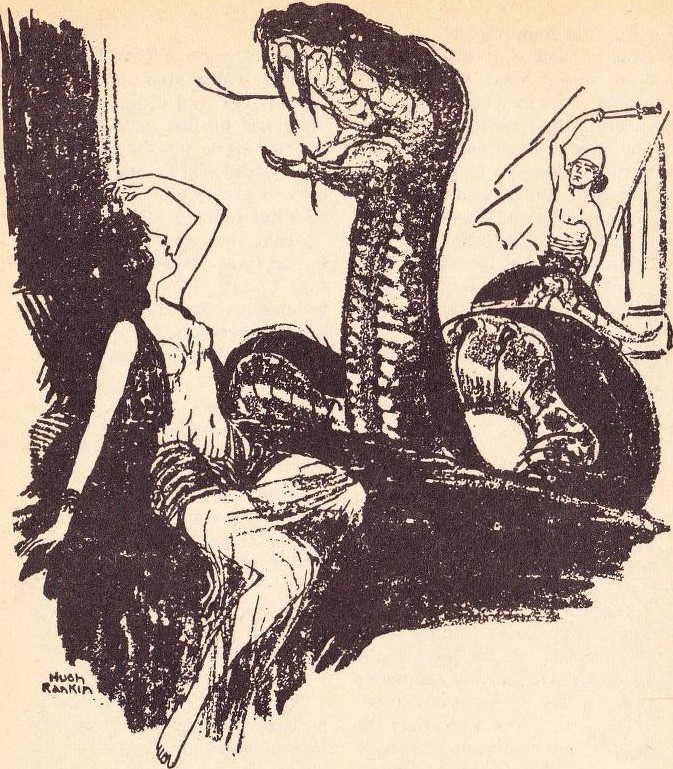

Illustrations by Hugh Rankin.

This opening scene is just a hint of the carnage to follow. The plot is a complex one, with various factions scheming against each other, betrayals, allies becoming enemies, and foes forced to work together. Frankly, I had some trouble following it. In brief, the sister wants to force Conan, now the leader of a group of hill people, to wreak revenge on the sinister forces that attacked her brother. This involves several of his men who have been taken prisoner by another realm. (It's complicated.)

Instead, Conan kidnaps the sister, hoping to exchange her for the freedom of his men. This plan is ruined when a sorcerer, betraying the dark forces for whom he was working, works with the sister's disloyal servant on their own scheme to rule the land, which results in the death of Conan's men. (I said it was complicated.)

Conan, his captive, and a horse.

After a whole bunch of wild adventures, with plenty of killings, the pair wind up at the mountain where four powerful sorcerers dwell, along with their less powerful minions and one ultra-powerful sorcerer. By this time, the sister's hatred for Conan has turned to love, just in time for her to be kidnapped from her kidnapper, if you see what I mean.

One of the many torments to which the sister is subjected.

I hope this gives you some idea of the breakneck pace, non-stop action, and frequent plot twists in this story. I lost count of how many people are slaughtered by sword or magic. (At one point, Conan acquires a magic item that protects him from deadly sorcery. This seems awfully convenient.) There are even battle scenes, with hundreds or thousands of warriors massacring each other.

There's plenty of weird magic as well, which may be the most interesting part of the story. I was particularly impressed by the floating cloud on which the four sorcerers travel.

Howard had an undeniably important influence on sword-and-sorcery fiction, and his imitators continue the tradition. (Brak the Barbarian, created by John Jakes, comes to mind.) The raw intensity of Howard's style and the bloodthirstiness of his plots aren't for all tastes. Personally, I prefer the wit and elegance of Fritz Leiber's tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

Three stars.

The Young One, by Jerome Bixby

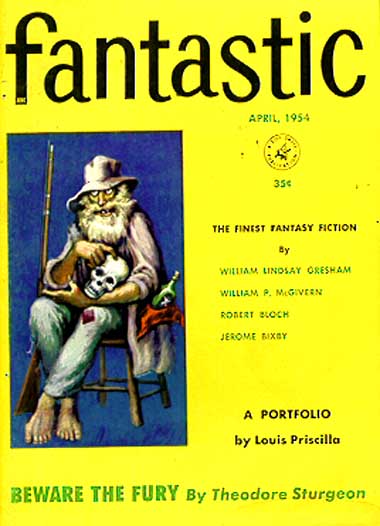

From the April 1954 issue of the magazine comes this supernatural yarn.

Cover art by Augusto Marin.

Jerome Bixby is probably best known to SF fans for his chilling tale It's a Good Life and the memorable episode of Twilight Zone adapted from it. He has also dabbled in screenwriting, coming up with the kind of B movies I enjoy, such as It! The Terror From Beyond Space.

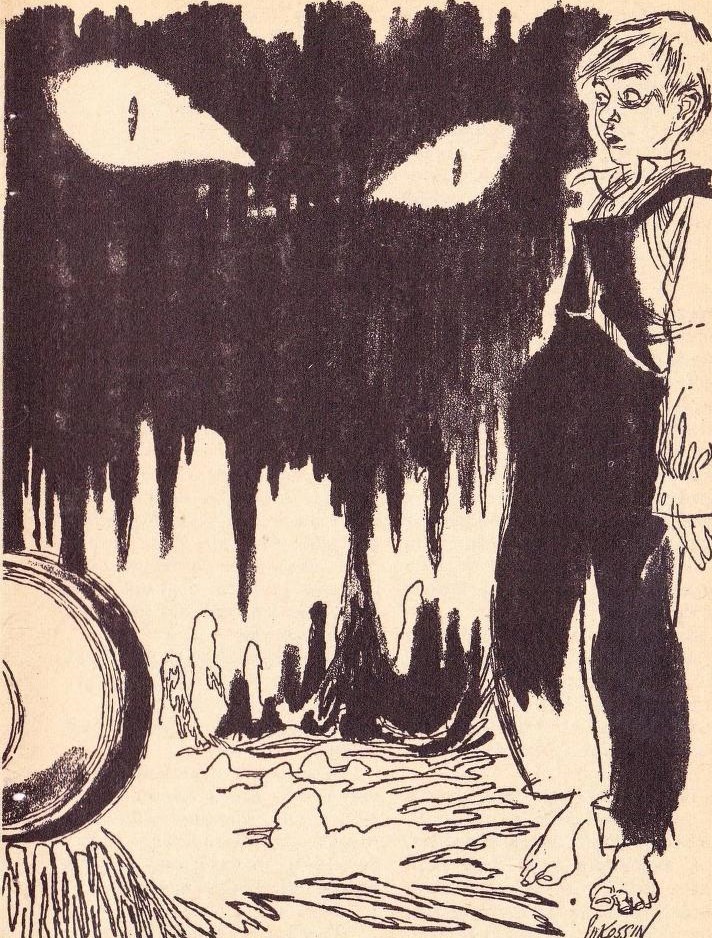

Illustration by Sanford Kossin.

A young boy meets a fellow his own age, newly arrived in the United States from Hungary. He seems nice enough, but all animals hate him. What's even stranger is that his parents eat raw meat and have very sharp teeth. (You can already see where this is going, can't you?)

The immigrant boy says he absolutely has to be back home before seven at night. The American kid tricks him by taking him into a cave, then pretending to be lost, so the Hungarian lad can't return until after his strict curfew. You can probably guess what happens.

It's an decent story, if predictable. (The exact way the plot is resolved may be a little bit unexpected.) The description of the cavern is intriguing, if nothing else.

Three stars.

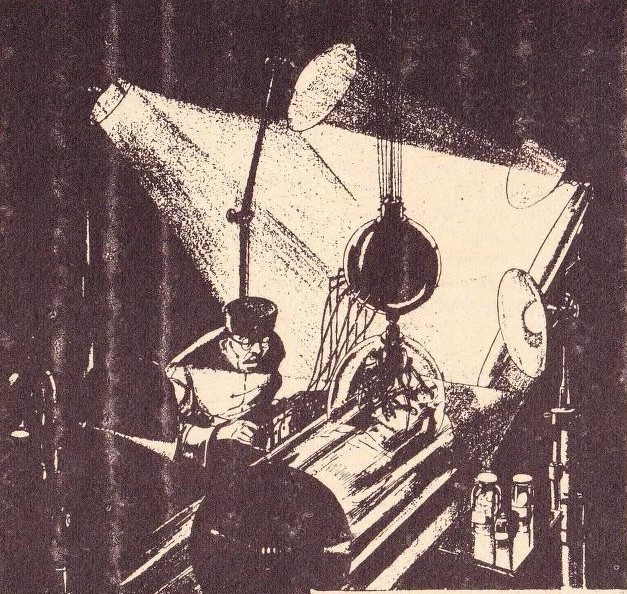

The Ambidexter, by David H. Keller, M.D.

This Kelleryarn comes from the April 1931 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Leo Morey

The world's two greatest surgeons, one American and one Chinese, have a meeting. The American has a brain tumor, so he wants the Chinese physician to remove part of his brain and replace it with part of a brain from another person. Can you guess that this is going to go very badly wrong?

Illustration by Leo Morey also.

This tale of Mad Science reminds me of old horror movies, the kind that show up on Shock Theater. In particular, the transplant theme brings to mind things like Mad Love, although that was about hands and not brains.

The partial brain transplant concept is unique, as far as I know, and Keller's background as a physician makes the crazy idea seem somewhat plausible. The character of the Chinese surgeon reeks of the old Yellow Peril stereotype, unfortunately. Replace him with, say, Boris Karloff and you might have the basis for a decent black-and-white chiller. I don't think the censor would care for the ghastly ending, however.

Two stars.

Mad House, by Richard Matheson

The January-February 1953 issue supplies this reprint.

Cover art by Robert Frankenberg.

Like Bixby, Matheson is associated with Twilight Zone and has written screenplays for feature films. His movies are too many to list, but a couple worth mentioning are the Jules Verne adaptation Master of the World and The Last Man on Earth. (Apparently Matheson wasn't happy with this version of his novel I am Legend, so he used the pseudonym Logan Swanson for his share of the screenwriting credit. I actually thought it was pretty good.)

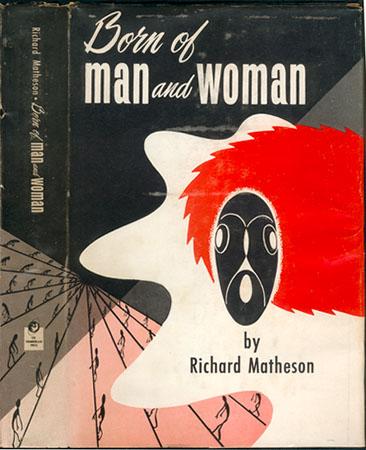

As with Howard's novella, Matheson's story has already been reprinted in a couple of collections. The first one is named after his first published story, already considered a classic.

Cover art by Mel Hunter.

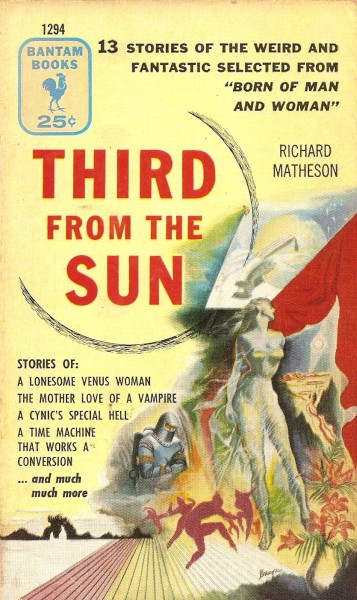

The second one is sort of a reduced version of the first one, omitting some stories.

Cover art by Charles Binger.

This psychological horror story features a frustrated writer who ekes out a living as a poorly paid instructor of literature. He's nearly always boiling over with anger about his inability to be published, lashing out at his students and just about everyone else. Fed up with his rage, his wife leaves him.

Illustrations by Bill Ashman.

He also fights a daily battle with inanimate objects around the house. They seem to be conspiring to harm him. An acquaintance — he can't be called a friend, given the fact that the main character is as nasty to him as he is to everybody else — suggests that the house is sort of absorbing his anger.

Chaos ensues.

Like other stories in this issue, it leads to a blood-soaked conclusion. It's also similar in that it's pretty predictable. The best part of it is the author's style, full of short, rage-filled sentences that really get you into the main character's head. That's not a very nice place to be, of course.

Three stars.

Worth All That Suffering?

The magazine ends with this appropriately macabre anecdote, which I offer without comment.

I don't believe it. Oh, wait a minute, that was a comment, wasn't it? Sorry about that.

Not a great issue, although a bare majority of the stories were at least worth reading. The Conan story is of historical importance, anyway. I suppose the magazine would be enjoyable enough if you happen to be in a situation where you need to be waiting around.

Cartoon by somebody called Salame, from the same issue as the Matheson story.

[Join us tonight for the next episode of Star Trek — airing at 8:30 PM Pacific and Eastern!]

![[December 8, 1966] Flesh and Blood (January 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Fantastic_v16n03_1967-01_0001-4-672x372.jpg)

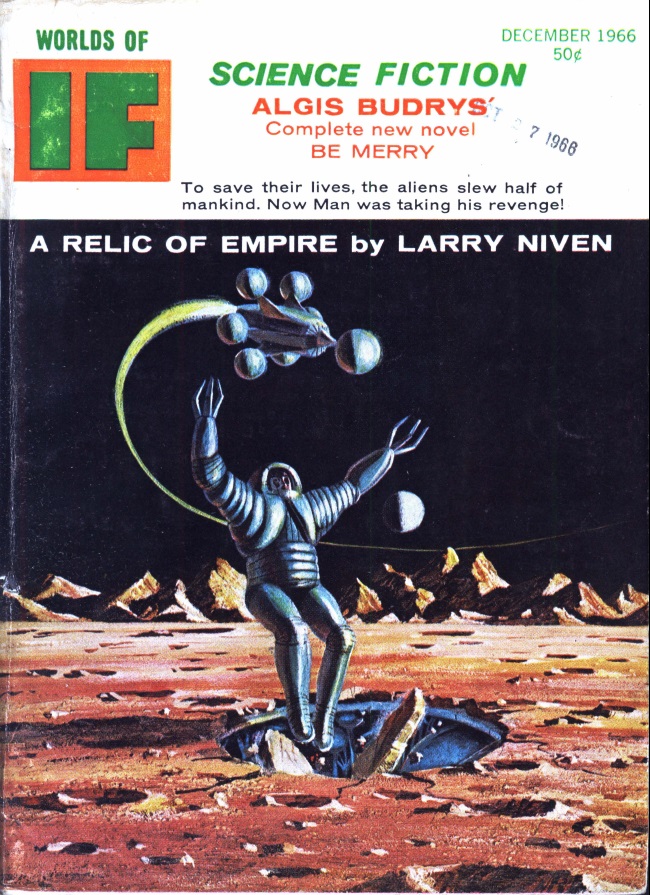

![[December 2, 1966] Mixed Bags (January 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IF-1966-12-Cover-665x372.jpg)

![[November 24, 1966] Middling (December 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)</big></b>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/amz-1266-cover-503x372.png)

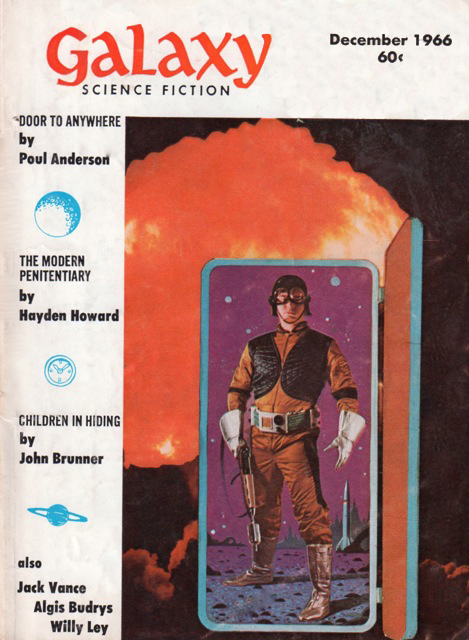

![[November 12, 1966] A Family Tradition (December 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661112cover-469x372.jpg)

![[November 6, 1966] Starting Over (December 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IF-1966-11-Cover-650x372.jpg)

![[October 16, 1966] Only the Lonely (November 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/fantastic_196611-3.jpg)

![[October 10, 1966] Let's Take A Trip (November 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v04n02_1966-11_0000-2-672x313.jpg)

![[October 2, 1966] At Heart (November 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IF-1966-10-Cover-646x372.jpg)

![[September 14, 1966] All the Old Familiar Places (October 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660912cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1966] The Bare Hardly-Essentials (October 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)</big></b>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/amz-1066-cover-491x372.png)