Today is the LAST day you can nominate for the Hugos. Please consider voting for Galactic Journey for Best Fanzine. And here are all the other categories we and our associates are eligible for this year!

by John Boston

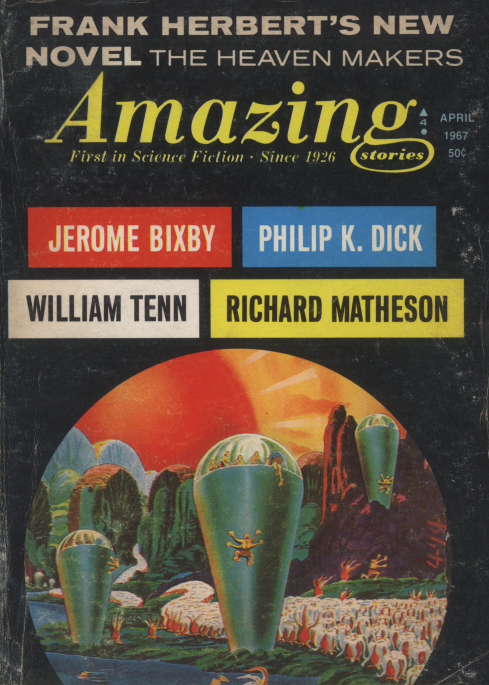

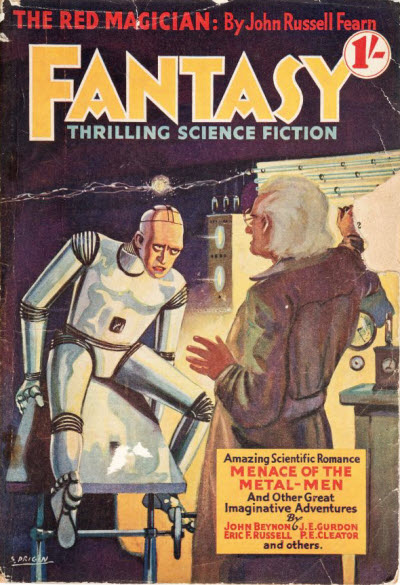

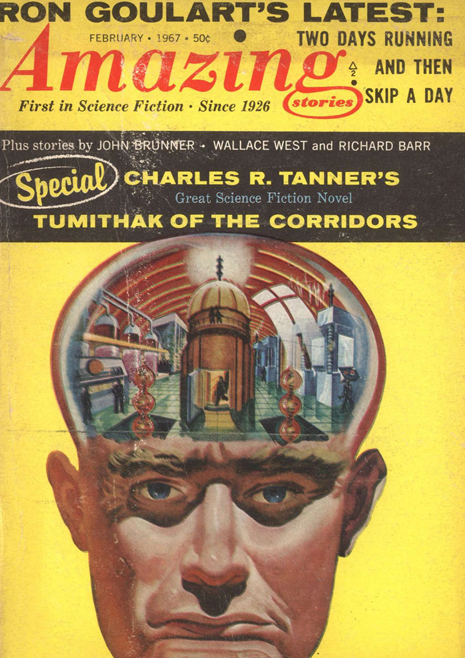

The April Amazing splashes an impressive array of marquee names on the cover: Hugo winners Frank Herbert and Philip K. Dick, the well-remembered sardonic satirist William Tenn, and Richard Matheson and Jerome Bixby, famous not only from the printed page but from celebrated Twilight Zone episodes made from their stories. The once prominent David H. Keller, M.D., is relegated to the inside of the magazine.

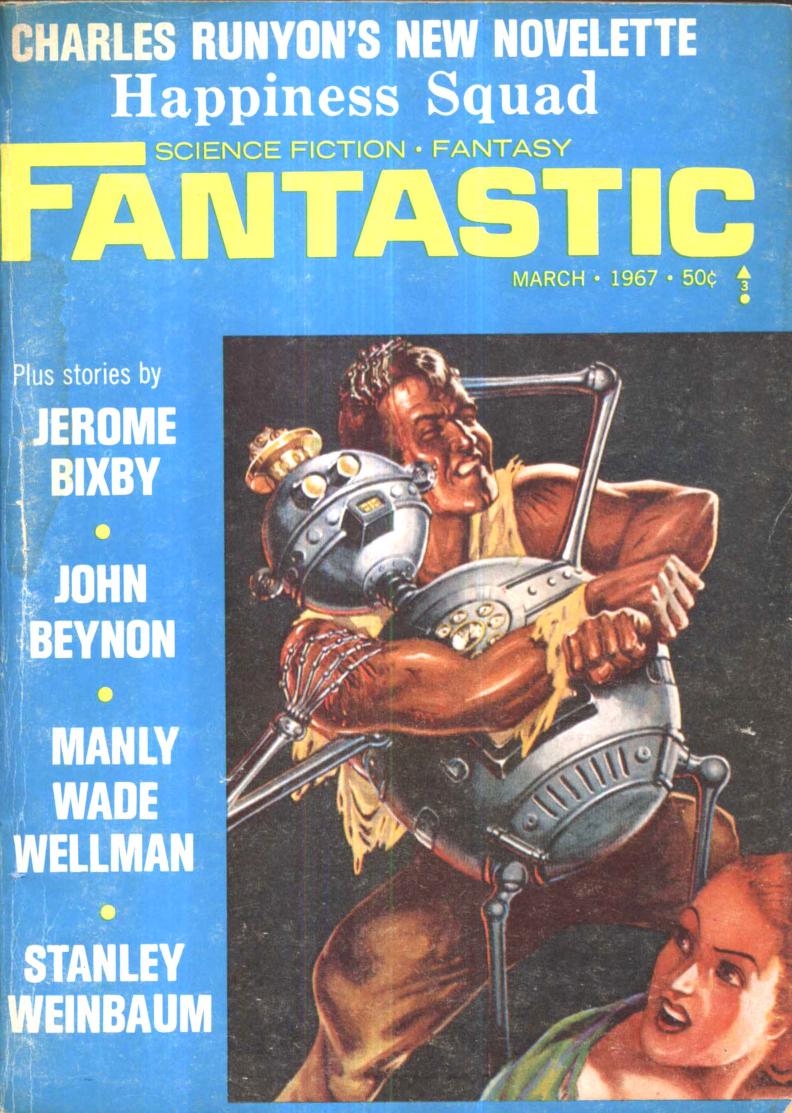

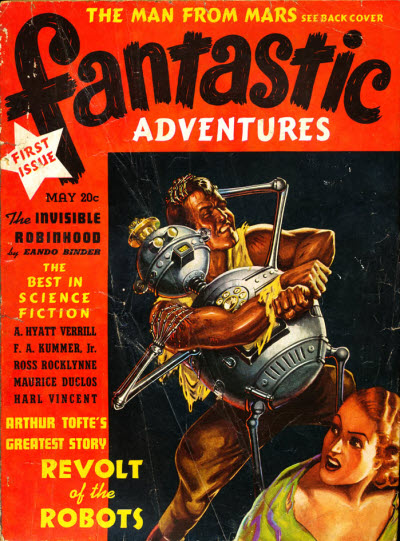

by Frank R. Paul

This blaze of celebrity serves to distract from the cover itself, which looks like it emerged from one of Frank R. Paul’s off days, though that is partly the fault of the present editorial regime; the picture is drastically cropped from its first appearance on the back cover of the July 1946 Fantastic Adventures, where it was considerably more impressive, though still far from the artist’s best.

This is one of the magazine’s accidental theme issues; I can’t speak for the serial yet, but the majority of the short fiction is at least partly preoccupied with domesticity, its meaning and its travails.

The Heaven Makers (Part 1 of 2), by Frank Herbert

by Gray Morrow

Frank Herbert’s The Heaven Makers is a two-part serial, and as usual I will wait for the end before commenting. The blurb says it “offers the chilling hypothesis that all the world really is a stage with each of us . . . its players.” How many times have we read that one? To be fair, new ideas are scarce these days, and treatment is all; it’s not the meat, it’s the motion, as a salacious old blues song has it. A quick glance at the first page reveals the dense and turgid writing for which Herbert has become known. To be fair (again), his virtues sometimes take longer to announce themselves than his faults.

The Last Bounce, by William Tenn

by Henry Sharp

William Tenn’s The Last Bounce, from the September 1950 Fantastic Adventures, is a remarkably bad story for the writer who at the time was several years past the classic Child’s Play and whose almost as well-known Null-P was a few months away. It’s a tale of stellar exploration, complete with mystery planet, deadly monsters, scientific mumbo-jumbo, and clichéd characters and dialogue. There’s even an embarrassing spacemen’s anthem, which shows up more than once. And domesticity (or its absence) rears its head! There is considerable musing about Why Men Risk All to Brave the Unknown and Why Their Women Put Up With It and Wait for Them. It would be nice to be able to read this as satire, but I can’t convince myself. More likely, Tenn made a barroom bet that he could write the most hackneyed piece of tripe he was capable of and some editor would buy it. You win! One star.

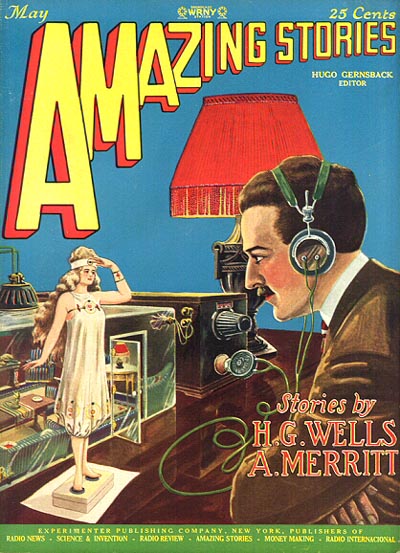

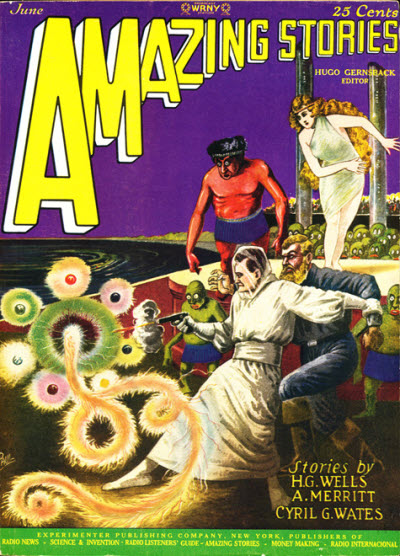

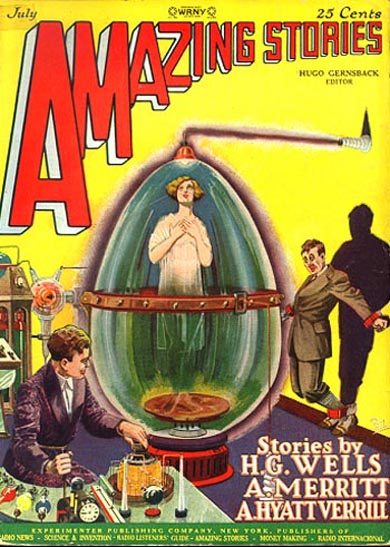

A Biological Experiment, by David H. Keller, M.D.

David H. Keller, M.D., is here with A Biological Experiment, from Amazing, June 1928—his third published story. The blurb says, correctly, that it anticipates 1932’s Brave New World. (You know the one about tragedy and farce? Here it’s the other way around.) Here is a veritable epic of domestic relations. Like Keller’s first story, Revolt of the Pedestrians, this one posits an extreme departure from our natural (well, familiar) social arrangements followed by a drastic reaction and restoration of the traditional. Unfortunately there’s entirely too much talk here, and the action that follows it is cartoonish.

by Frank R. Paul

In the far future everyone is sterilized at an appropriate age; marriage is “companionate,” easily terminable, and babies are made in factories and provided to couples who apply for and obtain the necessary permit. But Leuson and Elizabeth, a couple of young rebels, want to go back to the old ways. Why? Because no one is happy! Love has disappeared from the world!

So says Leuson, towards the end of a seven-page monologue. (Elizabeth says, midway through: “Tell me again why they are not happy. I have heard you tell it before but tell me again. I want to hear it out here in the wilderness where we are alone—together.”) Leuson has stolen some books from the Library of Congress, where he works, to learn the history and how to survive the old-fashioned way. The happy couple elopes (a word Leuson discovered in his research) to live happily in a mountain cave, along the way capturing a goat to milk. Unfortunately, far from modern medicine, Elizabeth dies in childbirth (good idea, that goat). Along the way it has been revealed that this was a covertly sponsored rebellion; the couple’s parents have subtly nudged them along towards this destiny.

And now, the plan’s consummation, at the annual meeting in Washington of the National Society of Federated Women! “Five thousand leaders of their sex had gathered for the meeting and every woman in the nation was listening to the proceedings over the radio.” Leuson appears, carrying a basket, and reprises his seven-page lecture. “On and on he talked and as he talked there arose in the hearts of the women who listened a strange unrest and hunger for something that had once been their heritage.”

And at the end of this spiel . . . “He reached down into the basket and, picking up his daughter, held the baby high above the heads of the five thousand women and showed them a baby, born of the love of a man and a woman in a home.” The finale: “And as they marched down Pennsylvania Avenue, the women of the nation cried in unison: ‘Give us back our homes, our husbands, and our babies!’” Fade to black.

Whew! Two overripe stars, barely.

Little Girl Lost, by Richard Matheson

Richard Matheson’s Little Girl Lost (Amazing, October/November 1953) is a capable potboiler, efficiently recycling with stock characters a stock plot of the 1940s and ‘50s—domesticity upended by the weird and threatening. Young Tina disappears in her living room; her parents Chris and Ruth can hear her but not see her or figure out where she is. What to do in the wee hours with an invisible child but call Chris’s friend Bill, “an engineering man, CalTech, top man with Lockheed over in the valley.” Bill quickly susses it out: “I think she’s in another dimension.” (Later, he adds, “probably the fourth.”) Meanwhile, in the spirit of the times, Ruth is more or less continuously hysterical.

by Ray Houlihan

And so is the dog, but to better effect. He’s whining and scratching to be let in, and when he is admitted—to keep from waking the neighbors—he runs straight to the dimensional hole the people can’t see, and now little Tina has company. Soon enough, Chris blunders partly into the hole, grabs kid and dog, and Bill pulls him out by his legs, which are protruding into our dimension. Domestic tranquility is restored, and they switch the couch and the TV so if anything goes through again it will be Arthur Godfrey. It’s facile and economical, and perfectly fashioned for TV; it made one of the better Twilight Zone episodes five years or so ago. Three stars.

by Bernard Krigstein

Philip K. Dick’s Small Town (Amazing, May 1954) is equally domestic, but not quite as domesticated, as the Matheson story. Here, the strains of a bad marriage exacerbated by an oppressive job burst out into the larger world. Verne Haskel doesn’t get along with his wife, hates his job, and finds comfort only in his basement, where, starting with an electric train layout, he has built a scale model of the entire town and tinkers with it constantly. As his frustrations build, he begins tearing things out of his faithful representation and remaking the model town, culminating in ripping out Larson’s Pump & Valve, the site of his torment, stomping it to pieces, and replacing it with a mortuary. And, of course, it turns out reality (or “reality”—this is after all PKD) now conforms to the fruits of Haskel’s tantrum—and things end with a suggestion (this is after all PKD) that there’s a higher power than Haskel keeping an eye on things.

Three stars, more lustrous than Matheson’s to my taste.

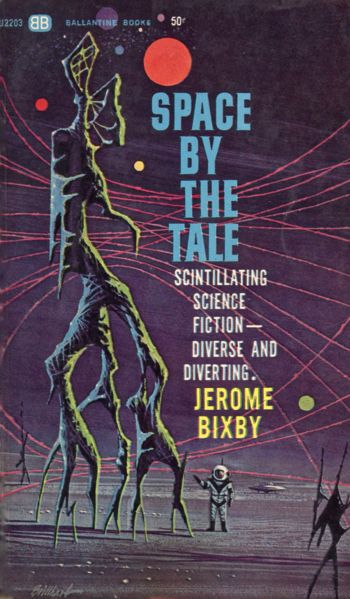

Angels in the Jets, by Jerome Bixby

by Paul Lundy

The issue winds up with Jerome Bixby’s Angels in the Jets (Fantastic, Fall 1952). At least one person likes this story; Frederik Pohl anthologized it in his 1954 anthology Assignment in Tomorrow. I disliked it when I read that book, and it hasn’t improved much since. Intrepid space explorers land on an inviting planet; one crew member is inadvertently directly exposed to its atmosphere, which renders her psychotic; she contrives to expose everyone else; and the protagonist, who has been out exploring while all this was going on, returns to the prospect of living in isolation as long as his bottled air holds out, or giving up, joining the crowd, and becoming psychotic right away. (Not much domesticity here, except for the hints of the deranged social order, or disorder, emerging among the psychotics.) A story that starts out at a dead end and consists of reaffirmations that it’s a dead end is not much of a story to my taste. But at least it’s well written. Two stars.

Summing Up

Hey, it's been worse in this bottom-of-the-market magazine. We have pretty readable and competent stories by Dick and Matheson and an amusing bad period piece by Keller, balanced against lackluster pieces by Tenn and Bixby; and the brooding prospect of Frank Herbert at length looms over it all as final judgment is postponed. Redemption? Maybe. To paraphrase generations of disgruntled baseball fans: Wait till next issue.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[March 14, 1967] Family Matters (April 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/amazing-apr-1967-cover-489x372.png)

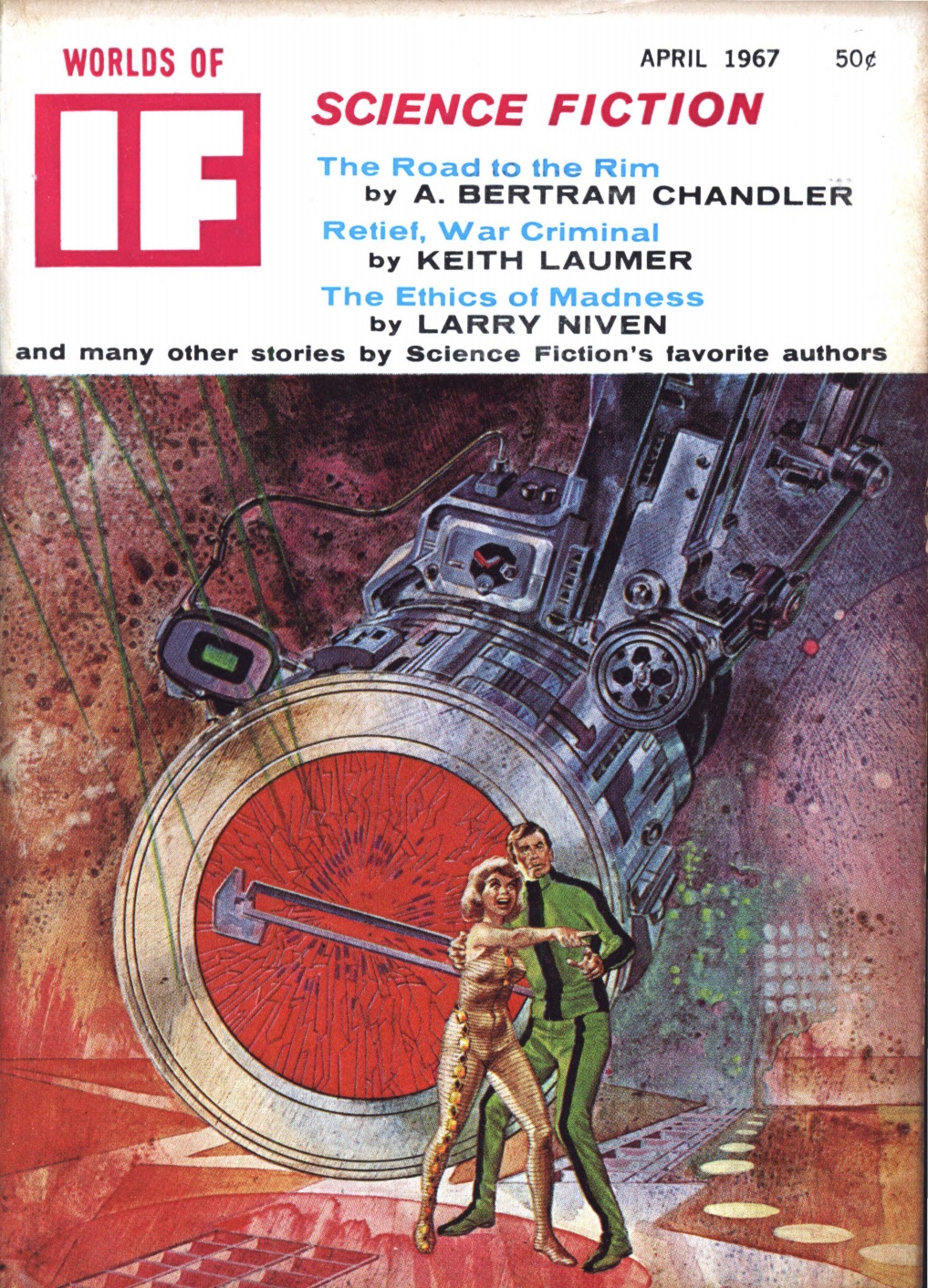

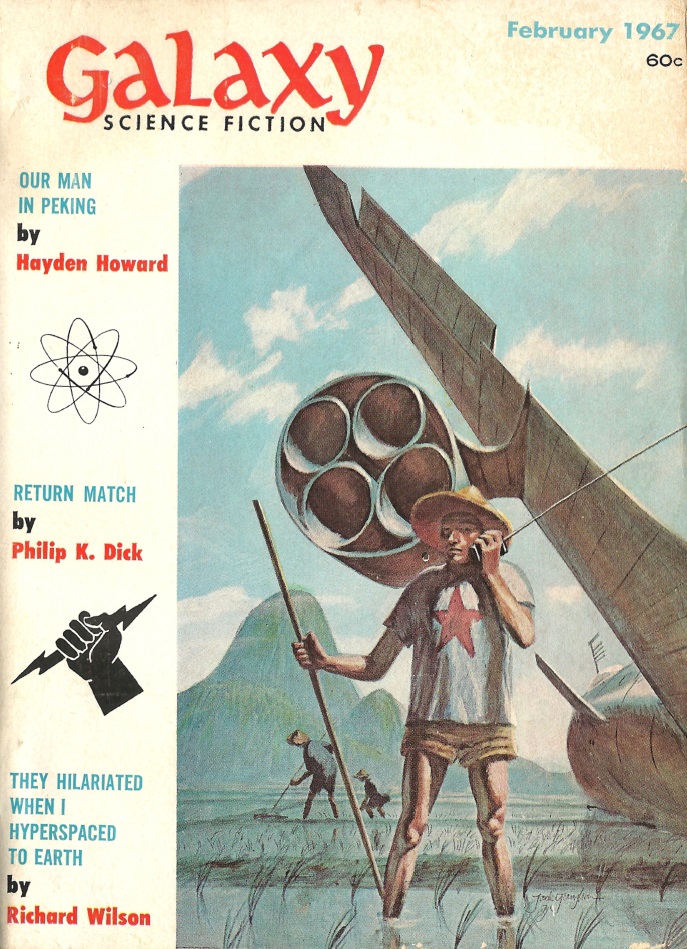

![[March 10, 1967] Mediocrités, Slayer of Magazines (April 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670310cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1967] Mediocrities (April 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IF-Cover-1967-03-672x372.jpg)

![[February 12, 1967] All's Fair in Love and War (March 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Fantastic_v16n04_1967-03_LennyS-cape1736_0000-2-672x324.jpg)

![[February 4, 1967] The Sweet (?) New Style (March 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IF-Cover-1967-02-full-672x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1967] Off to a Good Start (February 1967 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v04n03_1967-02_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[January 10, 1967] Return to sender (February 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 6, 1967] Happy Anniversary (February 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/amz-0267-cover-465x372.png)

![[January 2, 1967] Different perspectives (February 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/IF-Cover-1967-01-672x372.jpg)

![[December 20, 1966] Above and beyond (January 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i> and a space roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661220cover-656x372.jpg)