No man is an island; but without conventions, the moat can be pretty broad.

Humans are social creatures. Most of us have a natural desire to share our passions with others. When we read (or watch) science fiction and fantasy, we are receiving a broadcast from an author, but the communication stops there. If we want to discuss the experience, we need to find fellow fans.

There are many ways to do this. You can take out an ad in the newspaper's personal columns. You can join a local fan group, either public or privately sponsored. These venues let you find nearby fans, and many clubs have become formidable associations.

But if you want to meet fans from all over, or change your relationship with your favorite authors from a one-way experience into a face-to-face dialogue, there is no substitute for the convention.

The father of all science fiction conventions is the annual World Science Fiction Convention, at which the Hugo awards are announced. This year, it will take place in Pittsburgh from September 3-5.

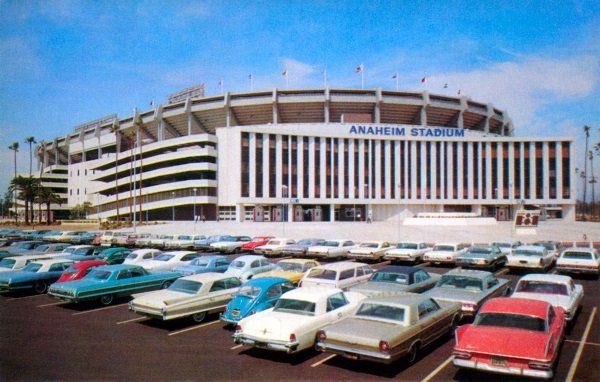

There are lots of smaller conventions, however. For instance, there recently was a small affair in Anaheim called "Wondercon" whose focus was comic books, science fiction, and animated films. Anaheim is very close to my home town of San Diego, so we decided to make a family weekend it.

It was a jolly time. Being a small convention, the folks were very energetic and creativity abounded. My daughter hawked mimeographed copies of her home-grown comic book, which the professional writers at DC purchased with gusto. My wife dressed as the Bat-Woman (of recent prominence in the Batman comics); she pulled it off quite well! I perused fanzines, expanded awareness of this column, vigorously discussed the ramifications of copyright and trademark laws, and gawked at the well-crafted costumes.

Genre great Robert Heinlein was not in attendance, but a fan circle devoted to him was there leading a blood drive. I also met up with the family of the late great Edgar Rice Burroughs, who fretted about the upcoming ACE paperback reprintings of the master's works. Apparently, ACE will not be paying royalties (the original works having fallen out of copright).

Without further ado, here is my slew of photographs from the convention. My apologies for the blurriness—it is my first time working with color film.

Attendees:

Rose Tyler

Peggy Carter

Amy Saunders (who is an excellent artist; contact her for some excellent comics-inspired and science fiction prints!)

As Anaheim is the home of Walt Disney's theme park, Disneyland, Disney costumes were popular:

Historical dress was also common:

Who doesn't like Captain America?

And, of course, Superman!

The Author, himself

By the way, the Wisconsin Democratic Primary is today. My bet is on Hubert Humphrey. After all, he is for all intents and purposes, the state's third Senator. I can't imagine an East Coast upstart like Jack Kennedy winning more than four of the ten delegates, no matter what the over-enthusiastic polls are predicting.

—

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.