by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

An interesting month for the Brit magazines, as there seems to be changes going on – again. More of which later, but I’m going to change convention this month and start with New Worlds, simply because it arrived first!

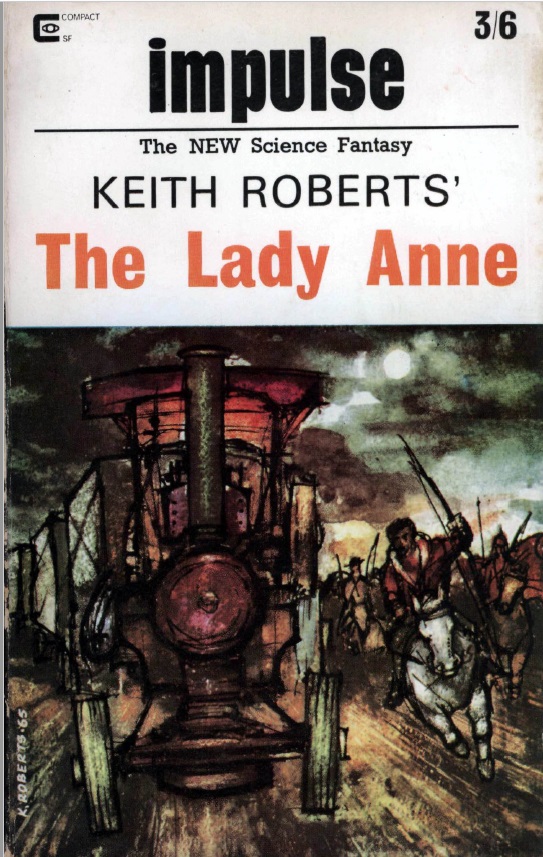

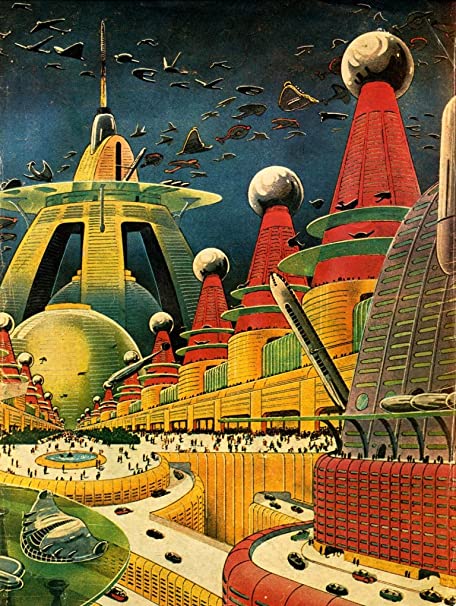

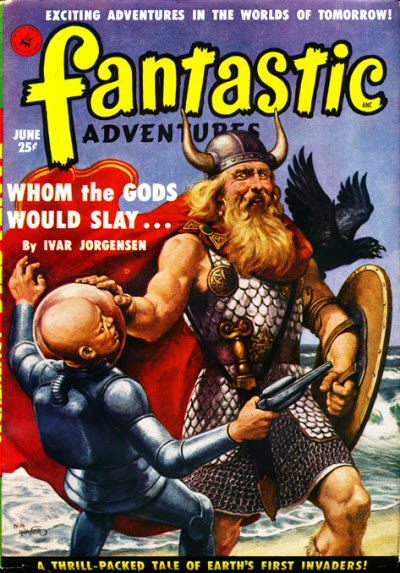

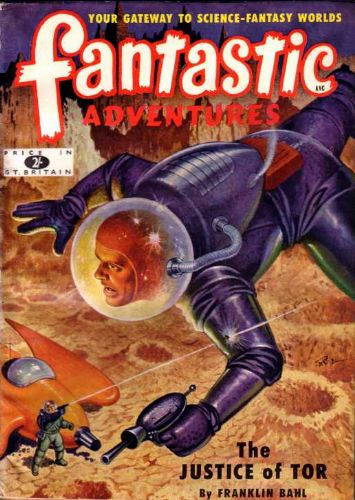

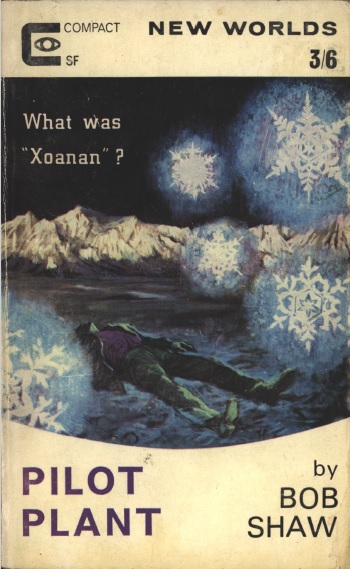

Terrific cover by Keith Roberts

The magazine is here.

Having had time off from writing the Editorial for a couple of months, editor Mike Moorcock’s back and clearly on a mission. His Editorial this month sets out his stall from the beginning as it once again tackles the often-taboo subjects of sex and religion in SF.

Regular readers will know that really this is actually nothing new – Moorcock’s mentioned these topics before, and often. My first review of New Worlds was of an issue with the Harry Harrison story The Streets of Askelon in it, which is mentioned here as an example of a controversial story. However, this time the stories are being used to provoke ‘head-on’, with Mike baldly stating in this Editorial that he is out to shock – ”… we anticipate a certain response to the stories in this issue…” .

Do they really shock, though? Whilst there are undoubtedly aspects that will be surprising and even be actively disliked by some readers, most of the stories cover themes and ideas already touched upon in both New Worlds and SF Impulse in recent months. The Streets of Askelon was published four years ago, and there have been similarly controversial stories since. (Langdon Jones's story I Remember, Anita is also mentioned, which I thought I hated, but actually liked!) In the last few issues there has been a regular trend of stories with a religious element to them, usually not positive, although at least they are often looking at it from a different angle.

Anyway, with the proverbial stall set, let’s get to the stories!

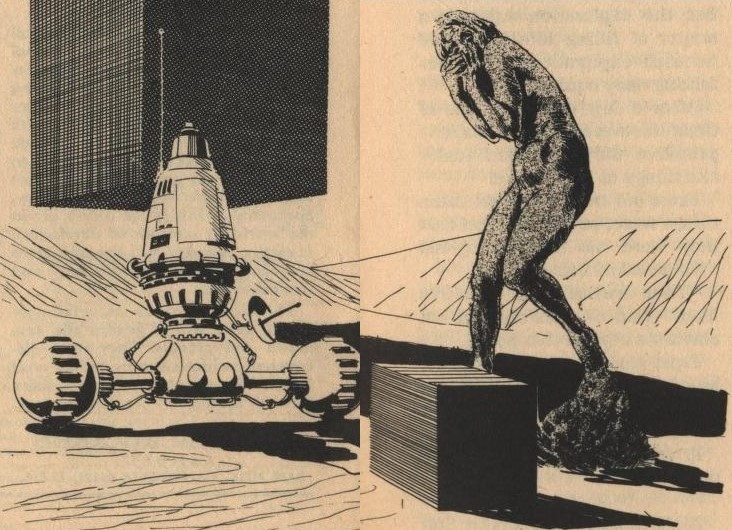

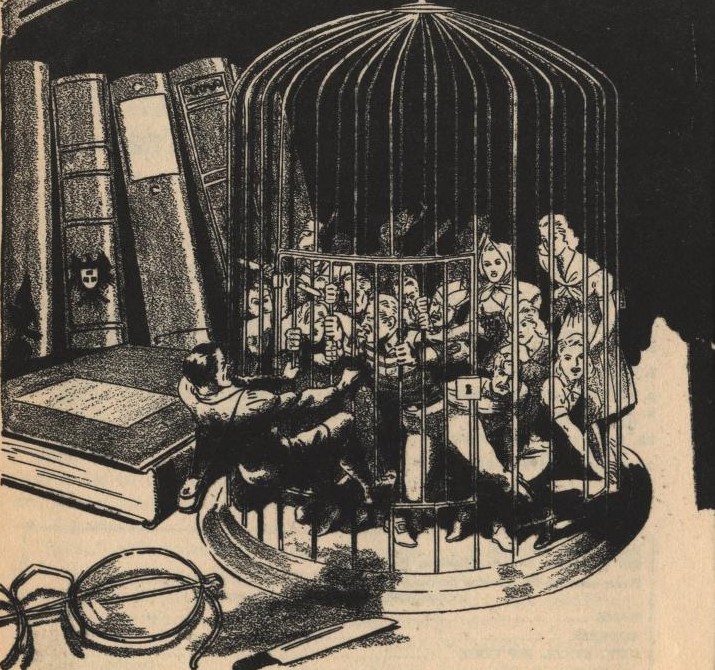

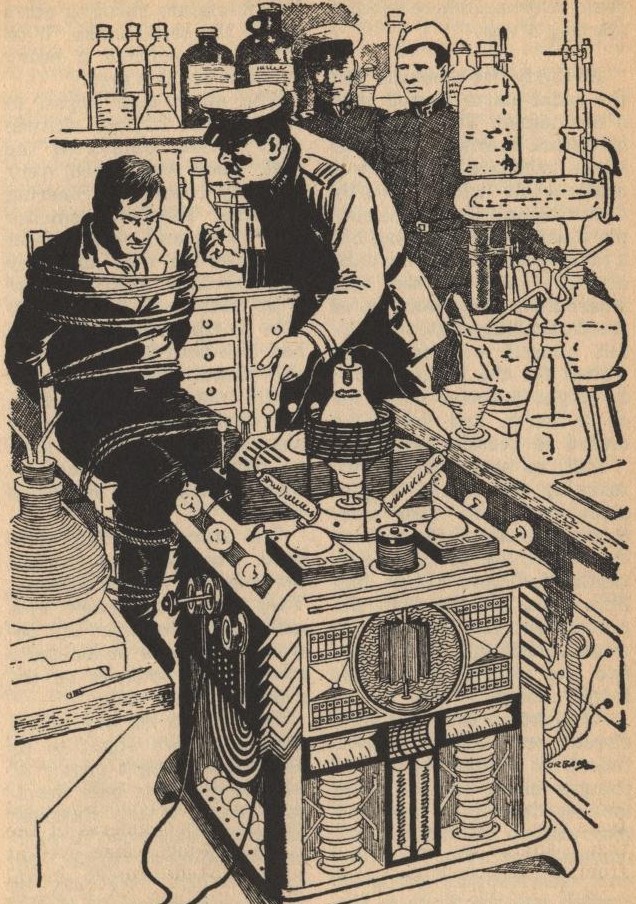

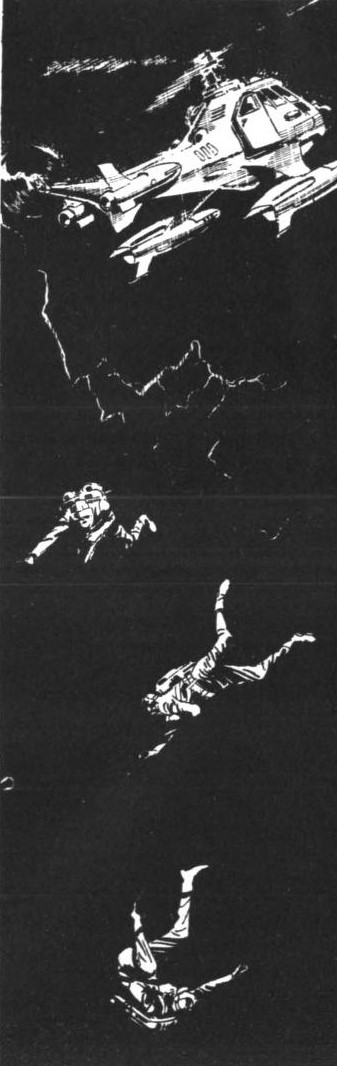

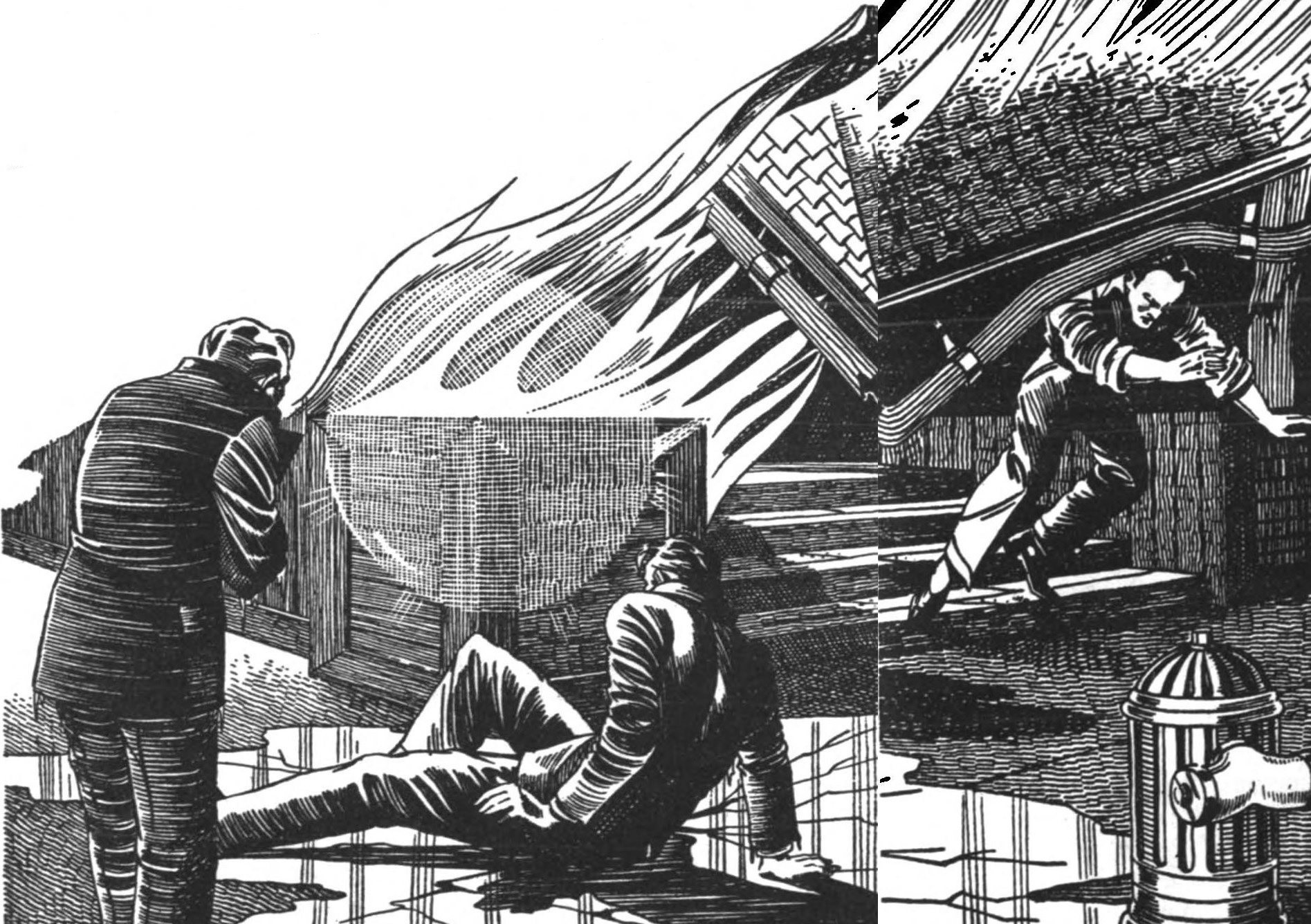

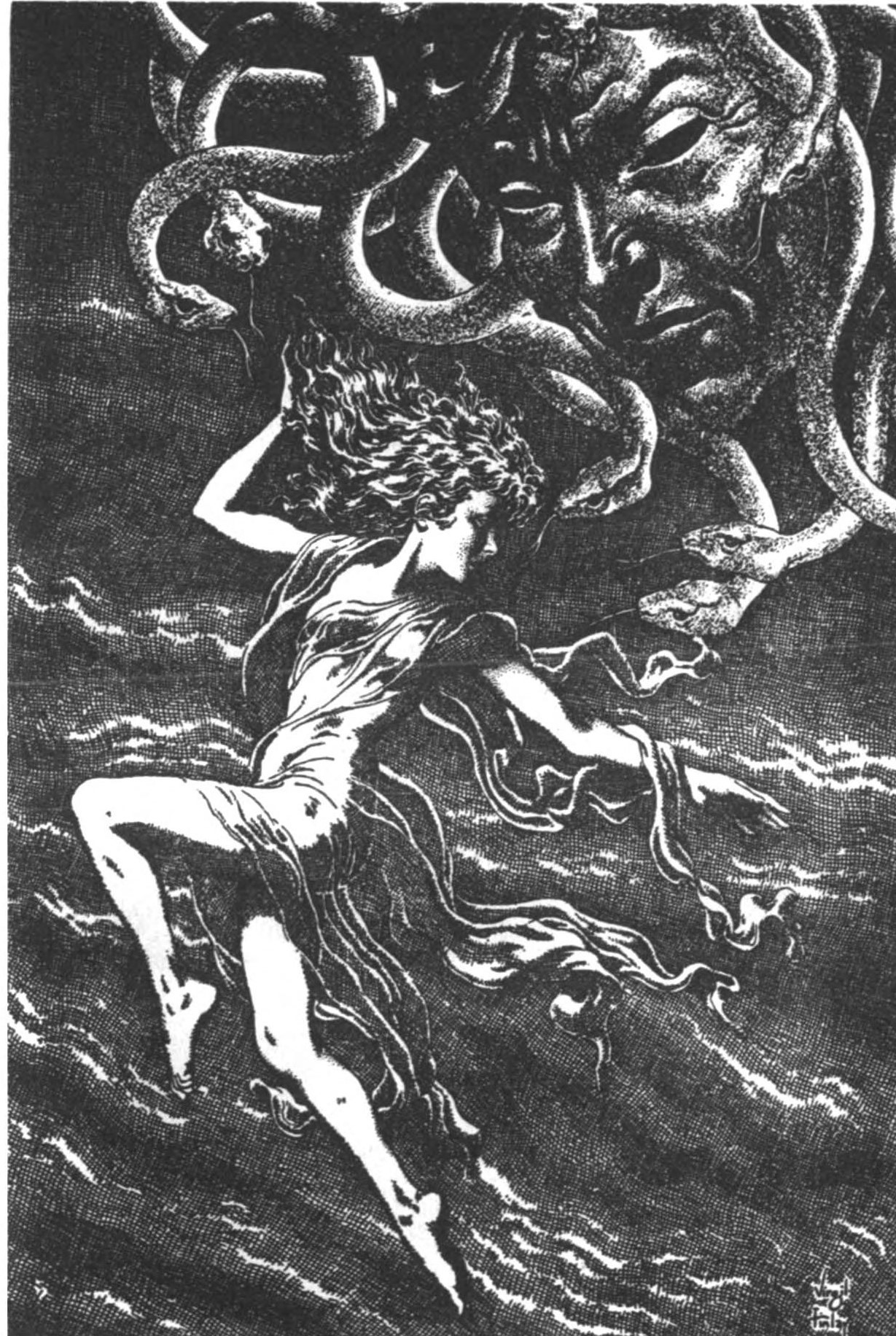

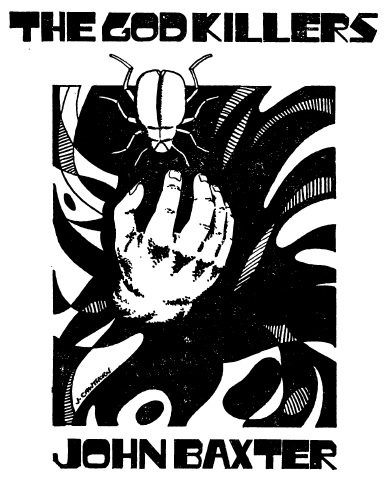

Illustration by James Cawthorn

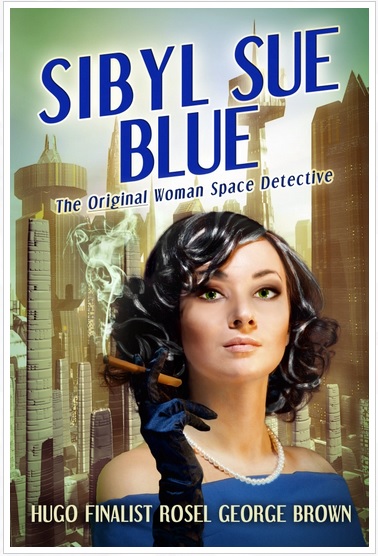

Behold, The Man, by Mike Moorcock

And to the big story of the month, given a dramatic cover by Keith Roberts. (I know I have been quite dismissive of some of Keith's previous covers, but this one I really like.)

Some may regard the story as deliberately provocative, a sensation-piece written with little purpose other than to gain attention and sales by means of creating outrage. The sort of thing that if it were in the newspapers would generate that “Did you read that?” response, followed by the outcry which then gets others to read it.

Personally, I am much more forgiving. If you’ve read any New Worlds or Impulse over the last year or so, you will find the main religious theme of this story there already.

Time-travelling Karl Glogauer lands in 29AD aiming to find the Nazarene Jesus Christ. He meets John the Baptist, and eventually Jesus. To Gloghauer’s horror, he finds that the Jesus he encounters is not the one expected from the Scriptures but instead a gibbering imbecile. Reluctantly Karl realises that he must take on the role and the responsibility and become what people in the future expect Jesus to be, even though he knows what will happen to him.

Having berated New Worlds for the clumsy story Look On His Face last month which covered similar ground, it would be easy to do the same here, but for the fact that this is a much superior tale. The character is nuanced, the story engaging and most of all surprisingly respectful towards the idea of religion. Although religion is undoubtedly central to the story, it also looks at loyalty, responsibility and duty, as well as the effect of symbolism and idolism on a mass of people to create a memorable story. I suspect that this is a story that will be remembered for a long time, even outside of the initial outrage. Another 5 out of 5. (That’s two in two months… a worrying habit!)

That Evening Sun Go Down, by Arthur Sellings

And then back to Earth with a bump. Another appearance of a regular author here, though one who’s rarely impressed me. That Evening Sun Go Down begins with something written in the style of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange before telling us it is another – yes, another post-apocalyptic tale. Space-filler, sadly. 3 out of 5.

Signals, by John Calder

A new name to me. The story of a scientist with a scientific discovery of “interatomic communication”, based around the atom, but instead of telling it like it would be in an Asimov story this keeps veering into talk about sex, which fits with the brief of the magazine but to me feels tacked on, presumably in an attempt to be controversial. Not really sure whether this is meant to be parody, but in places it does feel like it. 2 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

A Taste of the Afterlife, by Charles Platt and B. J. Bayley

This is an intriguing one, as a collaboration between two regulars. Platt is now recognised by the magazine as “Designer”, I see. The story is set in the future as Fairweather, our narrator, is given an assignment in some future Cold War – installations have been destroyed, apparently by some sort of interference beam or covert saboteurs, and it is his job to discover the cause. To do this, Fairweather must exist in the Afterlife, which involves killing him in order to travel there. An intriguing idea, but it all boils down to being James Bond-type stuff. It does sound a little like the movie Fantastic Voyage, which I gather was just released in the US – Jason has talked about it already. The novel is reviewed in SF Impulse this month, more of which later. 3 out of 5.

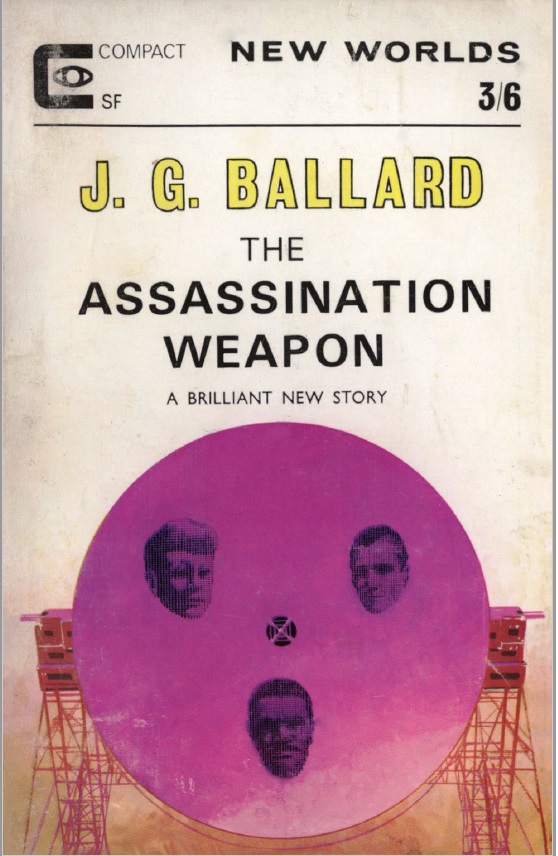

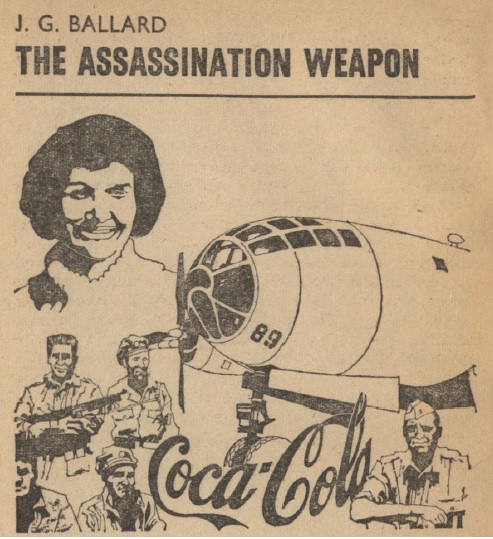

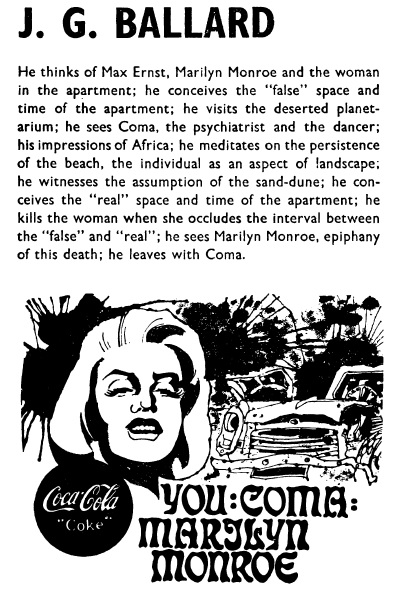

The Atrocity Exhibition, by J. G. Ballard

And on to a big-hitter with the return of J. G. Ballard. The title alone suggests that we’re back in Ballard-territory. Bleak, disparate, odd, memorable, peppered throughout with references to cultural and religious icons – the Madonna, Nagasaki, Elizabeth Taylor, Garbo. Really defies explanation, but this feels more like a return to form after the last couple of lack-lustre efforts. Nearly as good as the Moorcock story for me, although I am starting to feel that what once was startlingly original in style is now a little tired. 4 out of 5.

Another Little Boy, by Brian W. Aldiss

What! Another Aldiss story?

Interestingly, this one has an introduction from Aldiss that explains that it was inspired by a previous story by J. G. Ballard. Whilst I’m never a fan of authors having to explain their story, this one actually is not bad, and gives a whole new meaning to that phrase “Make Love, not War!” as in the future the commercialisation of sex and industrialisation of contraception has created a quite-different society to what we have now. Determined to celebrate the beginning of this enlightened age, the characters decide to re-enact the dropping of an atom bomb over Nagasaki. Sounds barmy – and it is! – but you can never accuse Aldiss of writing the same thing over and over. Silly, but entertaining. 4 out of 5.

Invaded by Love, by Thomas M. Disch

And talking of love, here’s another story involving it. Although he has been around a while, I think that this is my first read of material from another American who like Roger Zelazny is making waves with his New Wave stylings. This one fits Moorcock’s theme this month as it tackles religious belief head on and adds to this a drugs element. In the story an alien preacher arrives on Earth, attempting to sign humans up to his Universal Brotherhood of Love. As part of this the alien offers little yellow pills which eliminate violence and feelings of anger. As more and more people globally take the drug, war is eliminated but it also leads to unintended results such as world-wide famine as humans refuse to slaughter animals as well.

There is some resistance. An attack by the human resistance on the alien’s orbiting spaceship simply leads to the arrival of an alien fleet, which there is now no urge to attack. Eventually the world succumbs to this alien invasion.

This is a surprisingly dark tale, which reminded me a little of Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, without quite so much of the hectoring, or perhaps Arthur C Clarke’s Childhood’s End. Am sure Philip K Dick is writing similar stuff too, of whom more in a moment. The idea that invasion occurs not through war but by peace is an intriguing one. At times the story is a tad unsubtle, but overall, the story is quite impressive – I expect to read more from this promising writer. 4 out of 5.

Book Reviews

After his skewering of Goddard’s film Alphaville last month, John Brunner returns to criticise novels this month by exploring the work of Philip K Dick, who I’ve mentioned already this month.

As PKD is regarded as one of the New Wave of writers, perhaps unsurprisingly Brunner is also a fan of all of PKD’s work and as a result this month’s analysis is less eviscerating and more complimentary. It is well explained and detailed with an exhaustive list of novels mentioned at the end. Putting my cards on the table, I must say that personally Dick is an author I admire but not love. I generally prefer his short stories to his novels, but this article might even get me to try some of those PKD novels I haven’t tried yet.

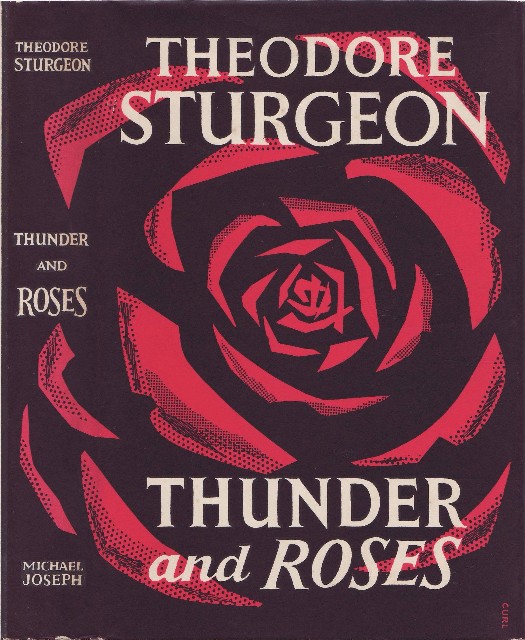

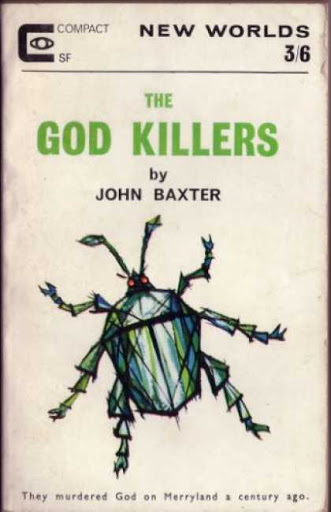

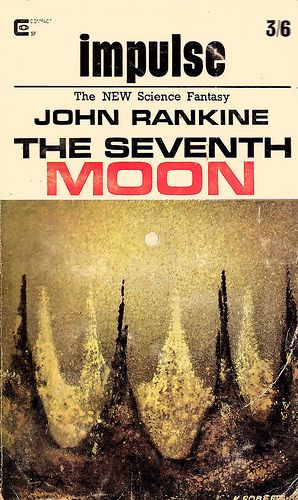

James Cawthorn then covers a trilogy of books all dealing with planetary exploration. This includes Hal Clement’s Close to Critical, John Rankine’s Interstellar Two Five and Trivana 1 by R. Cox Abel and Chas. Barren. He also reviews John Carnell’s New Writings in SF 8 and a couple of Compact SF publications (the publisher of this magazine coincidentally), including The Deep Fix by a certain James Colvin.

Lastly, Hilary Bailey reviews lots of items in brief this month. This includes Night of Light by Philip Jose Farmer, Bow Down to Nul by Brian Aldiss, Henry Kuttner’s Fury, Merril and Kornbluth’s Gunner Cade, Clash of Star Kings by Avram Davidson and rather weirdly, a non-fiction book The Family and Marriage in Britain by Ronald Fletcher. Well, I guess that it fits in with the theme of sex in the issue!

There are no Letters pages this month. It’ll be interesting to see how the mail-bag fills after this determinedly controversial issue.

Summing up New Worlds

I said last month that I thought New Worlds was one of the best for a long time. This one is, if anything, better. The Moorcock story is most memorable, but then the rest of the register – Ballard, Aldiss – is not too shabby either, and Disch is particularly impressive if a little unsubtle. The Editor’s insistence on including new names is still admirable, but also means some expectedly lesser efforts, but even there I have read worse. A very good issue overall, even if it is not as controversial as the Editor would like us to believe.

The Second Issue At Hand

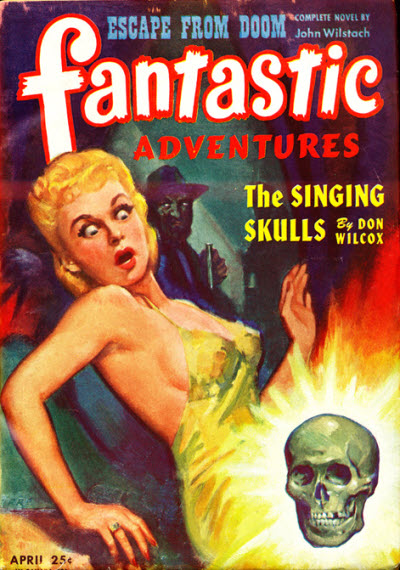

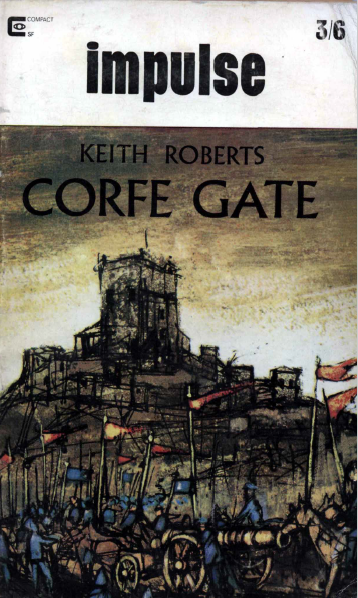

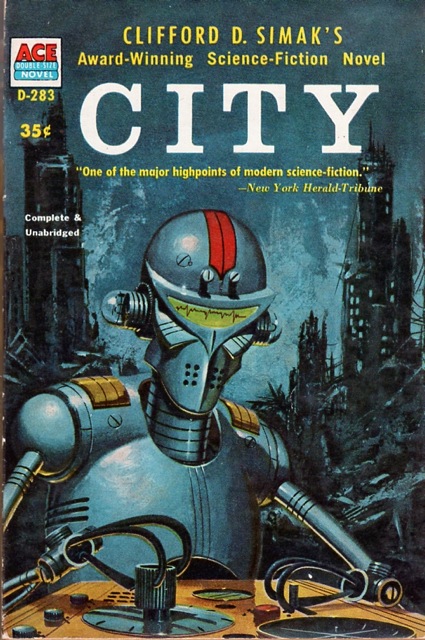

Another cover by Keith Roberts

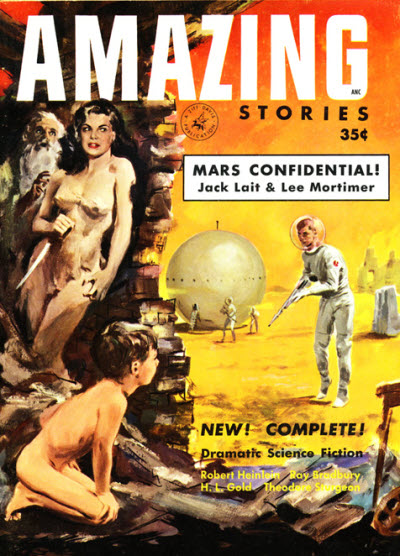

And after all that hullabaloo, let’s go to SF Impulse. Here there’s also controversy, as editor Kyril Bonfiglioli is stepping down. His editorial is short and brief – I’ll show it here.

Must admit, I felt that this was on the cards, although I expected the ending would be a little more graceful. I have said in recent issues how much Kyril seemed to be treading water, and this might explain it. Or perhaps it was the title-change to SF Impulse last month that was the last straw.

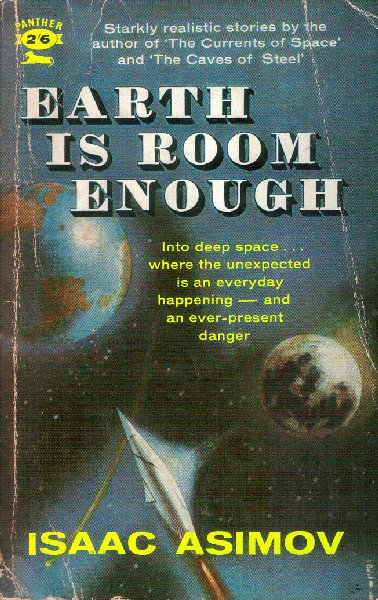

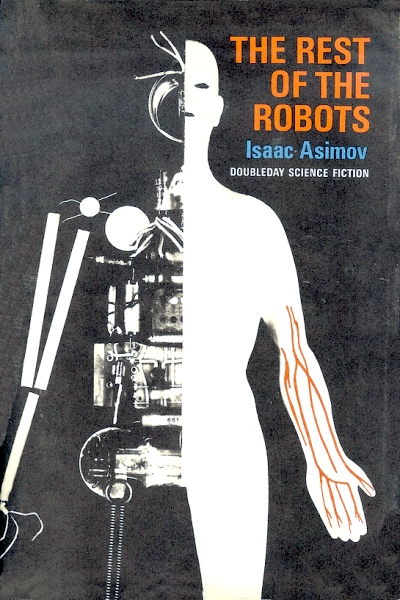

Harry Harrison in his new Editor role writes in Critique of the novelisation of the movie Fantastic Voyage, which I’ve already mentioned this month. He’s not a fan of the novelisation, although he is keen not to place blame solely with the “good doctor” Asimov.

An odd one, which is partly science fiction horror and partly allegorical, I think. A strange lily plant grows in the North Sea, and Jalovec, a scientist, is sent to a nearby oil rig to determine what it actually is. It seems that the plant is telepathic and generates emotional responses in those humans around it. When the plant’s effect spreads to Britain, catastrophe ensues. I did wonder if this was a take on the social drugs movement and “flower power”. At a more visceral level it reads like a psychedelic version of Day of the Triffids.

I was more intrigued by the claim at the top on the banner that Boyce’s last story, George in the June issue of Impulse was popular, as I didn’t like it. But then what do I know? I’m not sure I love this one, either. 3 out of 5.

Martians at Dick’s End by Daphne Castell

Good to see the return of a female regular here, but as the title suggests, the story is a parody. Martians crashland near a remote farm at Dick’s End – cue lots of low-level sniggering – and the narrator tells of how their blacksmith grandfather and his fellow villagers help the Martians fix their ship. In the meantime these white furry aliens acclimatise by speaking with quotes from television, and learn pub games like shove ha’penny.

As I’ve said before, these either work for you or they don’t. For me, they usually don’t, although this one I found gently amusing. I must admit that it does bring a degree of levity after the rather po-faced Boyce story, although it would never happen in The Archers (a British radio soap opera, been running about 15 years now). 3 out of 5.

Timothy, by Keith Roberts

And the return of the ever-so-busy Mr. Roberts, who seems to be keeping the magazine going almost solo at the moment. Many will be pleased at the return of Keith’s Anita, the naughty teen witch of many a previous issue.

Personally, the Anita series has varied in quality for me – usually depending on how much Anita’s Granny is in the story – but they are often entertaining. This latest story tells of Timothy, a scarecrow Anita made last Spring and who she has now decided to bring to life. As expected, chaos ensues when Timothy falls in love with her. It reads rather like a British version of Disney’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice from Fantasia. Light and inoffensive, but might just satisfy the demand for more Anita stories. 3 out of 5.

The Writing Man by M. J. P. Moore

A new name to me here. It is one of those experimental stories that reads as a stream of consciousness until the twist at the end, which I saw coming from a long way away. It’s been done before, perhaps too many times. 2 out of 5.

Audition by Fred Wheeler

A new name. A mercifully short story.

Jodrell Bank receives a communication from space, which it replies to. Other countries then attempt their own responses, which leads to the killer last line. (Not.) More filler. As a brief story it reads more like a joke told in a pub. It is OK but you’ll never remember it once you’ve finished the magazine. 2 out of 5.

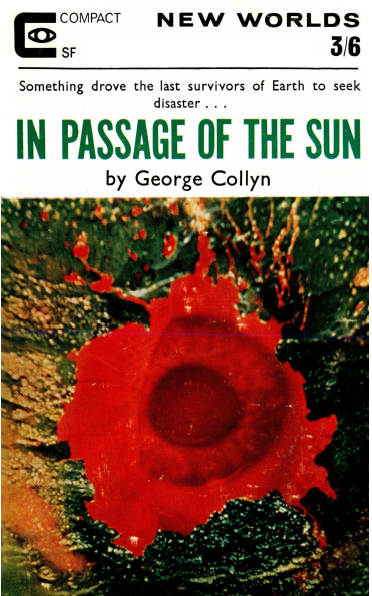

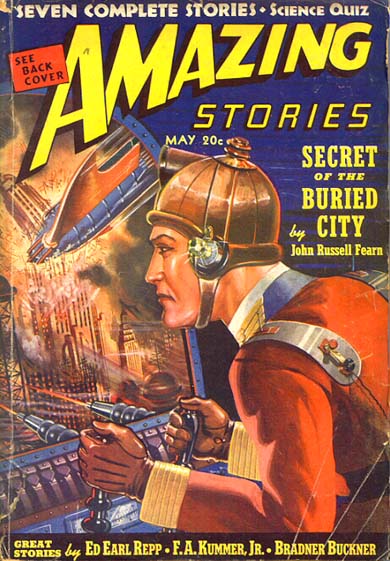

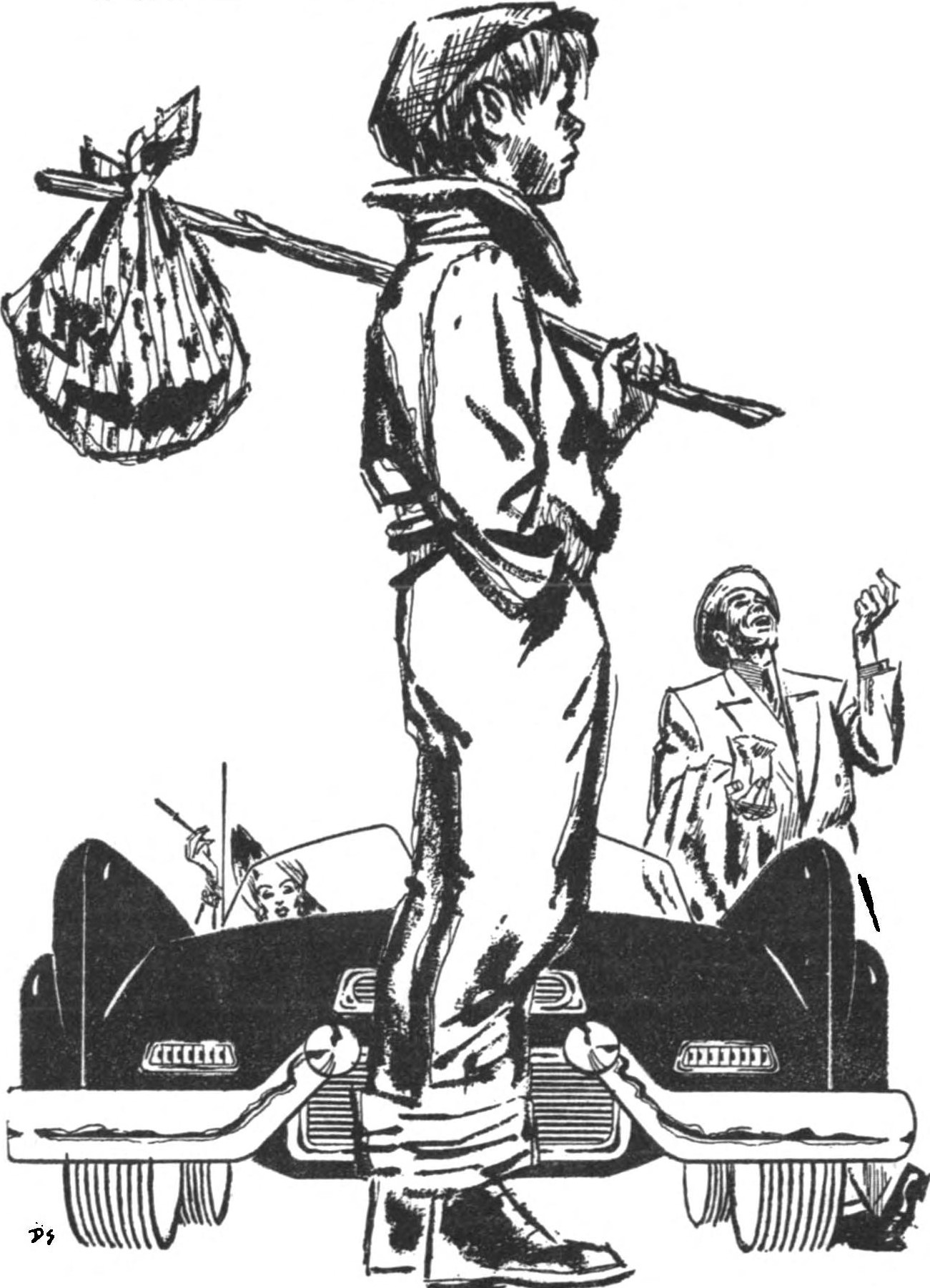

Make Room! Make Room! (Part 2 of 3), by Harry Harrison

Last month, I gave the first part of this a 5 out of 5 rating, something I don’t think I’ve ever done before. Admittedly, whilst it is basically a detective story set in a future dystopian setting, I was impressed by the nuanced characters and the descriptions of shabbiness and squalor in a world of overcrowded excess, crime and with a lack of resources.

This time around, Police Detective Andy Rusch is still investigating the death of crime boss “Big Mike” O'Brien. However, his relationship with O'Brien’s mistress Shirl has become complicated to the point where she moves in with Andy and his older friend Sol. The perpetrator of the crime, teenager Billy Chung, leaves the city and escapes to the decrepit Brooklyn Navy Yard where he meets Peter. Peter is another vagrant who is convinced that the world will come to an end at the oncoming millennium, but despite this the two find solace in looking after each other.

The story is still bleak. Much of it is about the situation around Andy and Shirl, which shows us unremitting squalor and decay. Whilst the O'Brien investigation is ongoing, it seems to take a step back here for the story to concentrate on other aspects. None of the characters come out of this well, yet their reasons for being like this in a dog-eat-dog world are clear.

I was interested to see if the story maintained its high score from last month, and I’m pleased to say that mainly because of the vivid imagery it still does. So again, 5 out of 5. We still have the murder to solve in the final part – I am interested to read how this one ends.

Summing up SF Impulse

This is not a bad issue. It could have been Kyril’s attempt to throw in anything left in the slush pile, but under the steering hands of Keith Roberts, it’s not that different to normal. Which raises the question of how long Roberts has been doing this for, with Kyril taking the credit.

In short, it’s another middle-mark issue overall, with some very good (e.g. the Harrison) and some not to my tastes. It’s not a disaster, which it could have been, but it is clear that there’s some filler here. My response is tempered by the fact that I realise how much hard work is going on behind the scenes to get an issue – anything like an issue – out on time.

Summing up overall

With everything going on this month, it perhaps shouldn’t be too much of a surprise for me to suggest that New Worlds is the significant ‘winner’ this month. Like Harrison’s novel for SF Impulse last month, the Moorcock story alone is almost enough to guarantee a win, but to which is also added a Ballard and an Aldiss which I thought were superior fare. More importantly, New Worlds shows a coherence and a quality that SF Impulse seems to lack. It is perhaps not surprising, though. It’ll be interesting to see if future issues of SF Impulse alter much with the change in management.

Until the next…

![[August 28, 1966] Messiahs and Resignation (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, September 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)

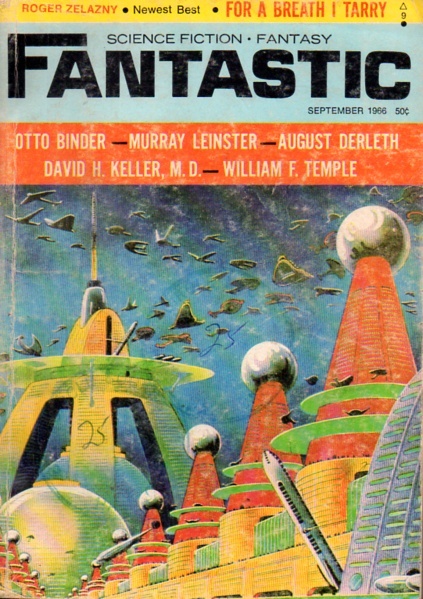

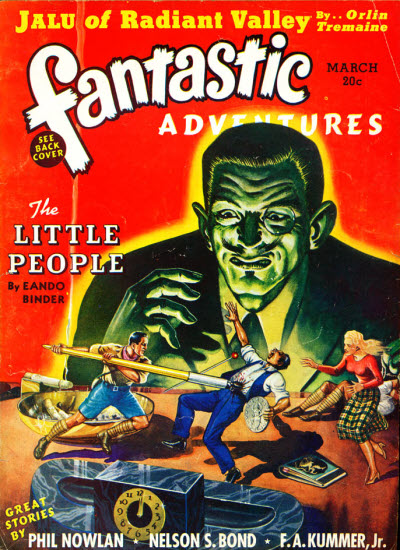

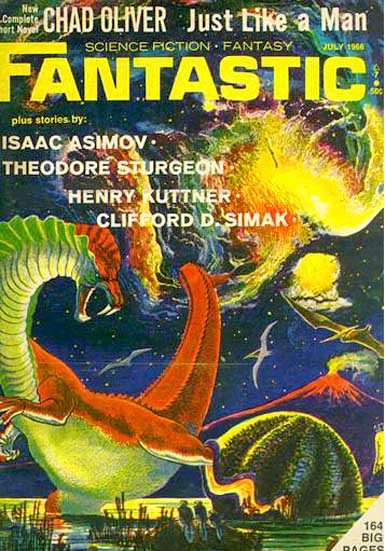

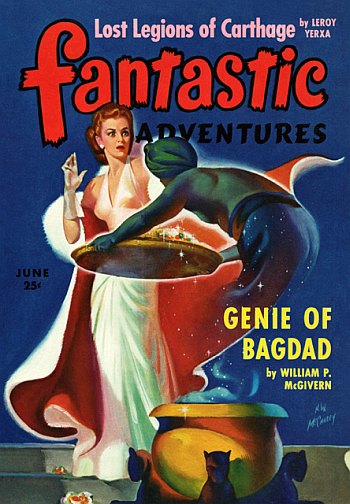

![[August 10, 1966] Dollars and Cents (September 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/FANTSEP1966-3.jpg)

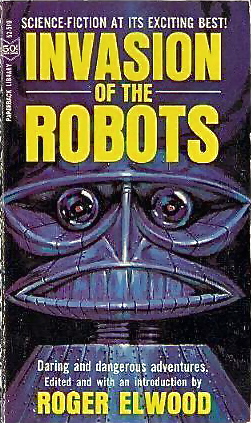

![[July 28, 1966] Cat People and Overpopulation (<i>SF Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, August 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Impulse-NW-Aug-66-672x372.jpg)

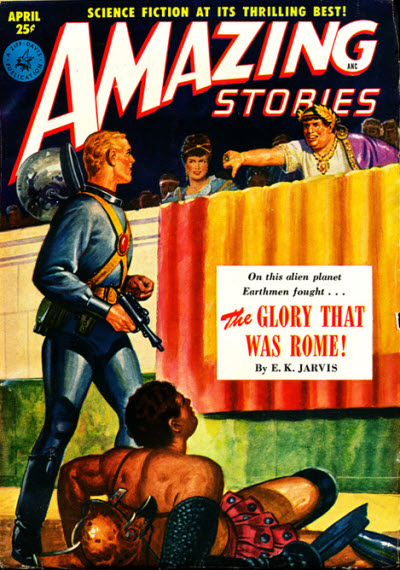

![[June 28, 1966] Scapegoats, Revolution and Summer <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, July 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Impulse-NW-July-1966-672x372.png)

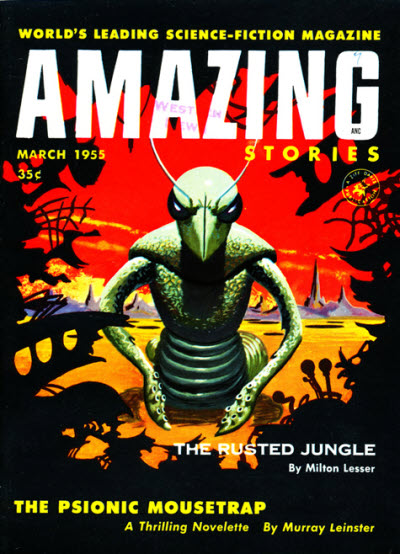

![[June 10, 1966] Summer Reruns (July 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/fantastic_196607-2.jpg)

![[May 24, 1966] Hatchetmen, Marilyn Monroe and God Killers (<i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, June 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Impulse-New-Worlds-June-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[April 26, 1966] Inner Space, Romance and Religion <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, May 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Impulse-NW-May-1966-619x372.jpg)

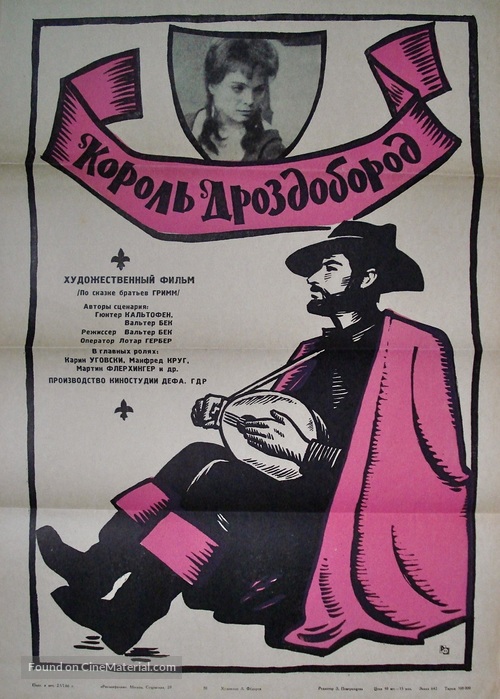

![[April 10, 1966] A Fairy Tale from the East: <i>King Thrushbeard</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/02-junger-Reiter-Manfred-Krug.jpg)

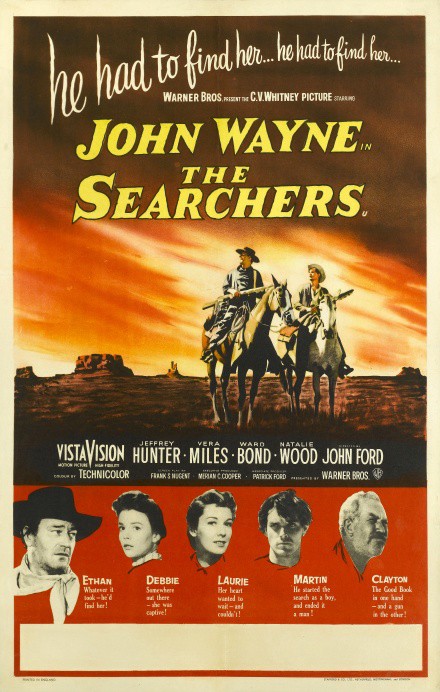

![[April 8, 1966] Search Parties (May 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Fantastic_v15n05_1966-05_0001-4-672x372.jpg)

Here's a picture of Representative Ford and wife Betty on a recent fishing trip, so you'll recognize him if his face shows up in the news in times to come.

Here's a picture of Representative Ford and wife Betty on a recent fishing trip, so you'll recognize him if his face shows up in the news in times to come.

![[March 26, 1966] Steam Tractors and Ballardian Mind Games <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, April 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Imp-New-Worlds-April-1966-672x372.jpg)