by Cora Buhlert

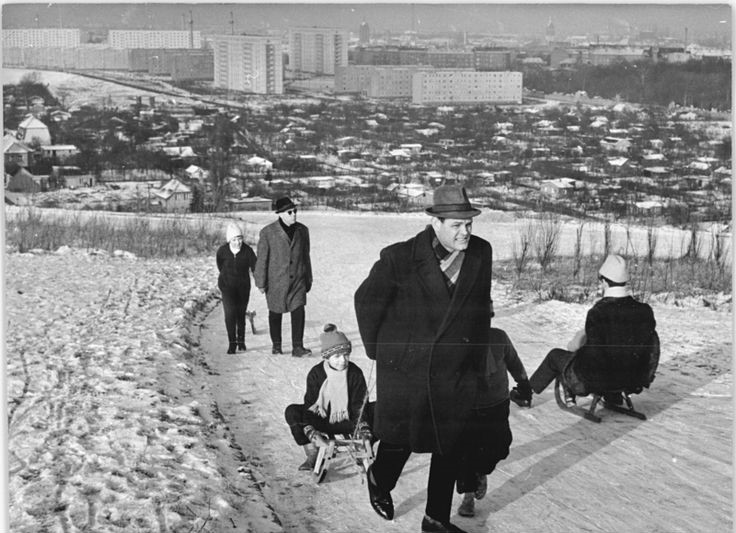

Winter in the City and the Park

It's cold a wet February here in my hometown of Bremen, but the first signs of spring are already visible and audible in the form of the red and white pavilions and the shouts of the barkers of the Bürgerpark tombola.

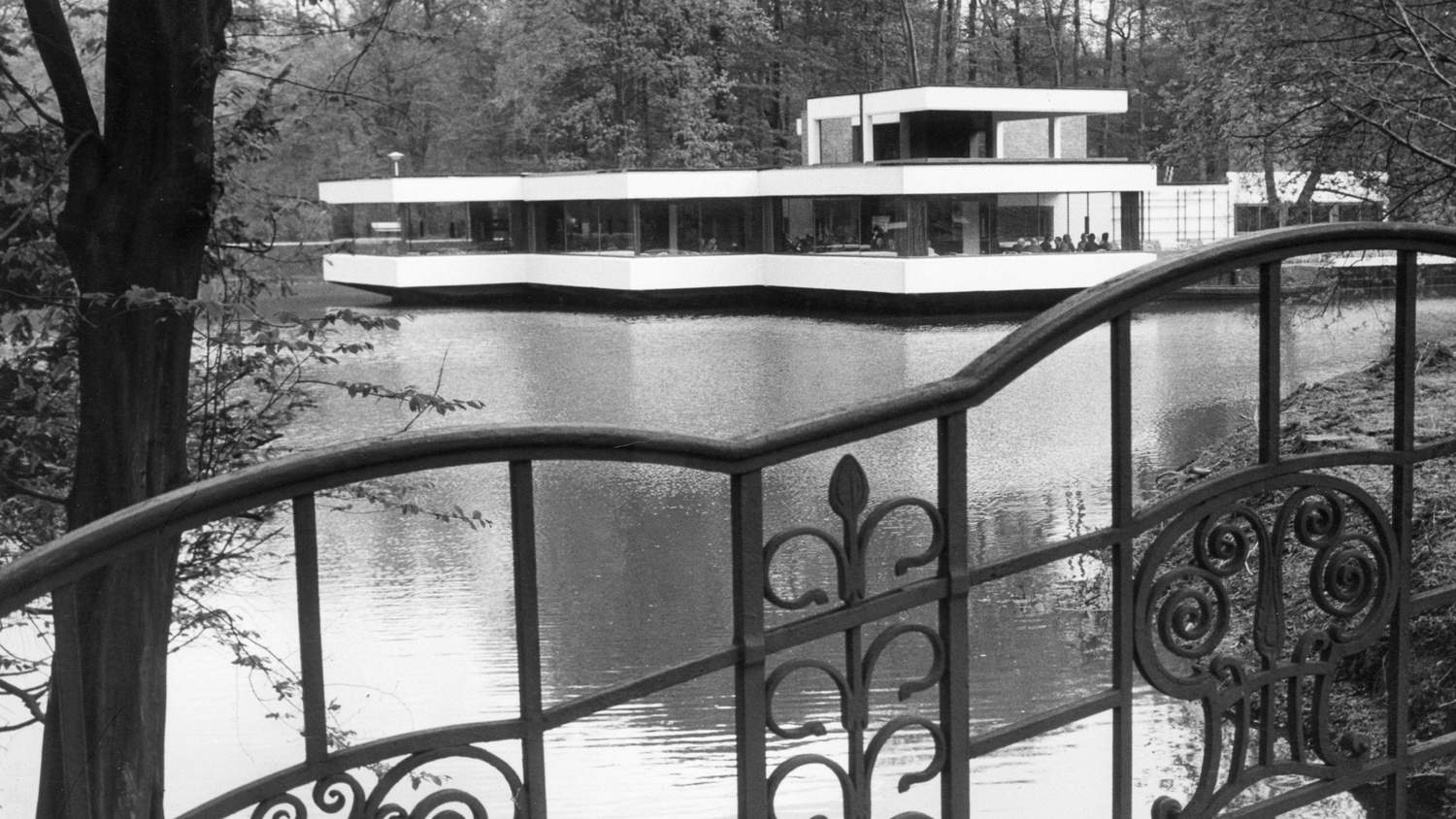

The Bürgerpark (citizen's park) is a roughly 200 hectare big park in the heart of Bremen, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. The park contains several lakes, a luxury hotel, a restaurant, a coffee house, a theatre, a small zoo as well fountains, bridges, benches, statues and lots of beautiful scenery. Beloved by the people of Bremen, the upkeep of the park is financed almost entirely by donations as well as the Bürgerpark tombola, a charity raffle that has been going on every year since 1953 in the late winter and early spring.

Whenever I chance to find myself in the city center at Bürgerpark tombola time, I inevitably buy a few tickets. After all, it's for a good cause and you can win some great prizes such as cars, holiday trips, sports tickets or cruises. Though so far, all I won was a packet of rice.

More from the Cimmerian Barbarian

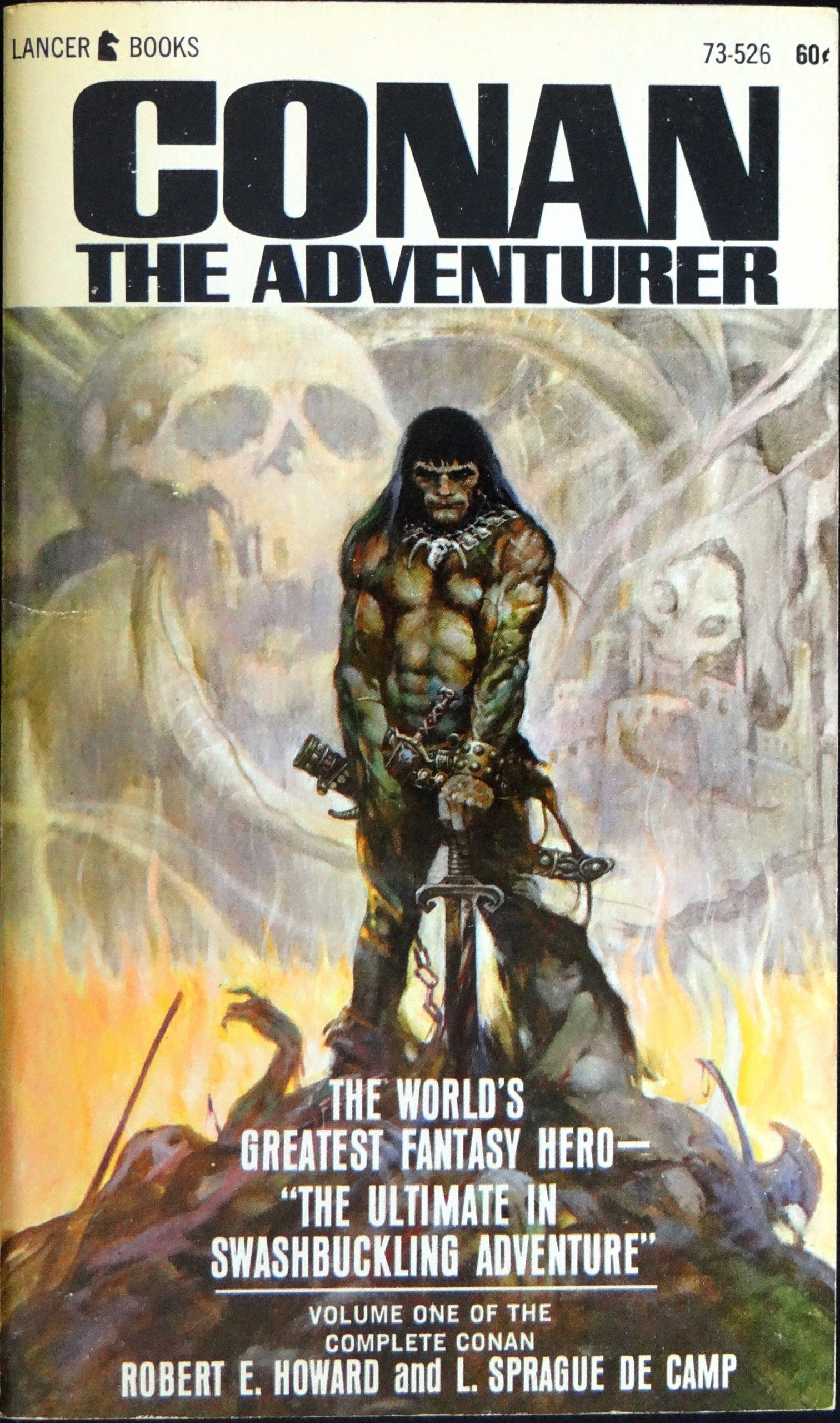

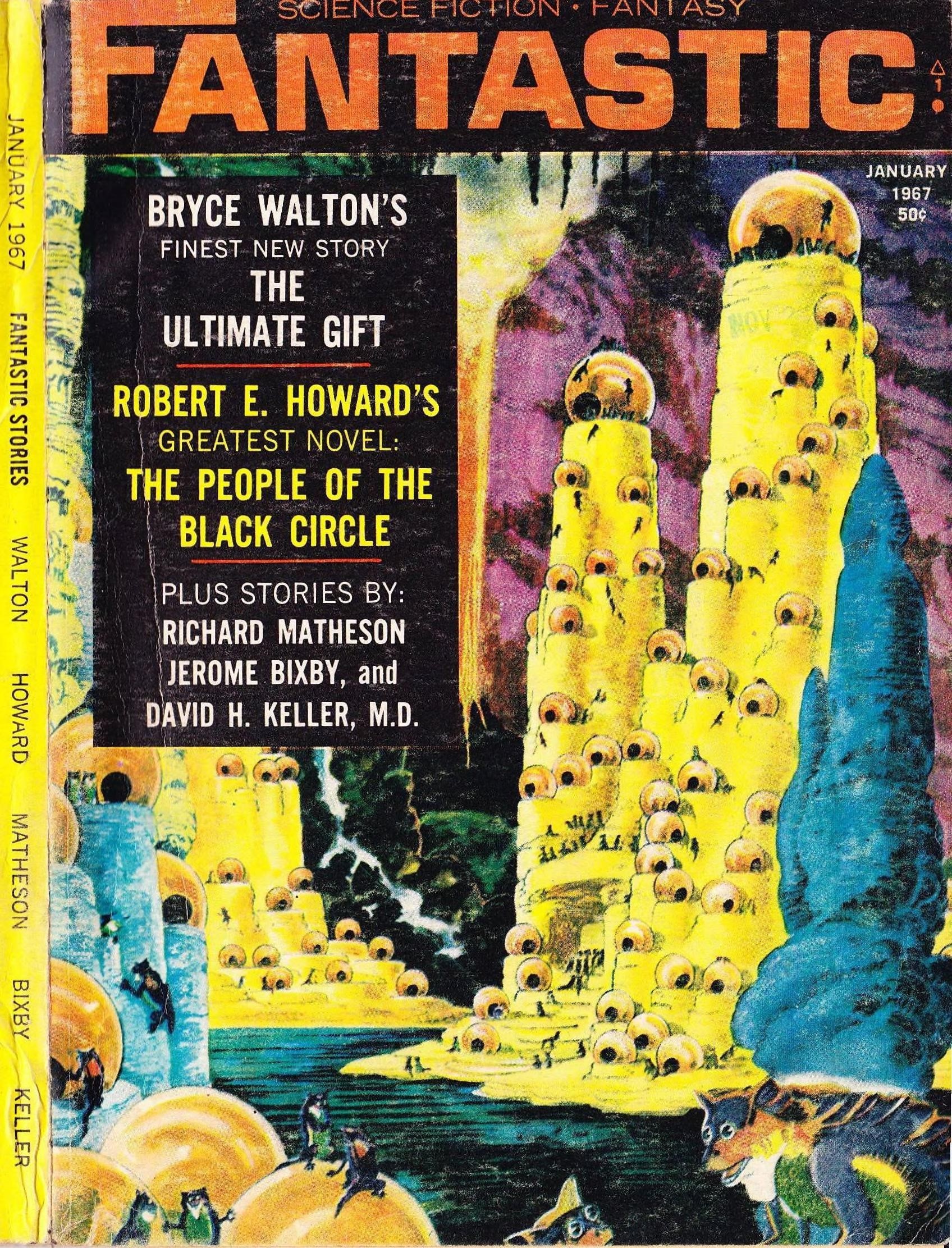

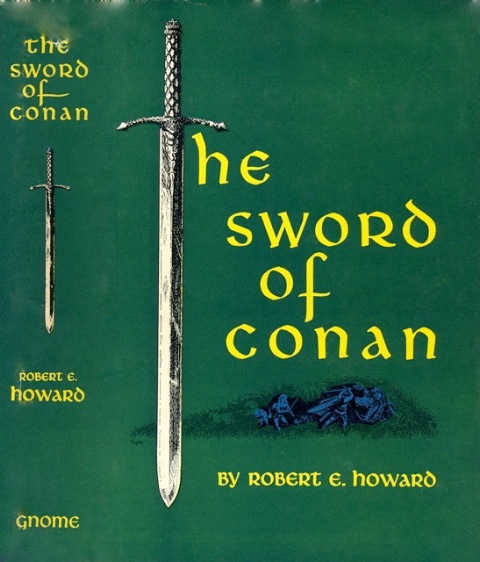

But even though I only won an underwhelming prize from the Bürgerpark tombola, I did hit the reading jackpot this month with yet another great collection of Robert E. Howard's Conan stories from the 1930s courtesy of Lancer Books.

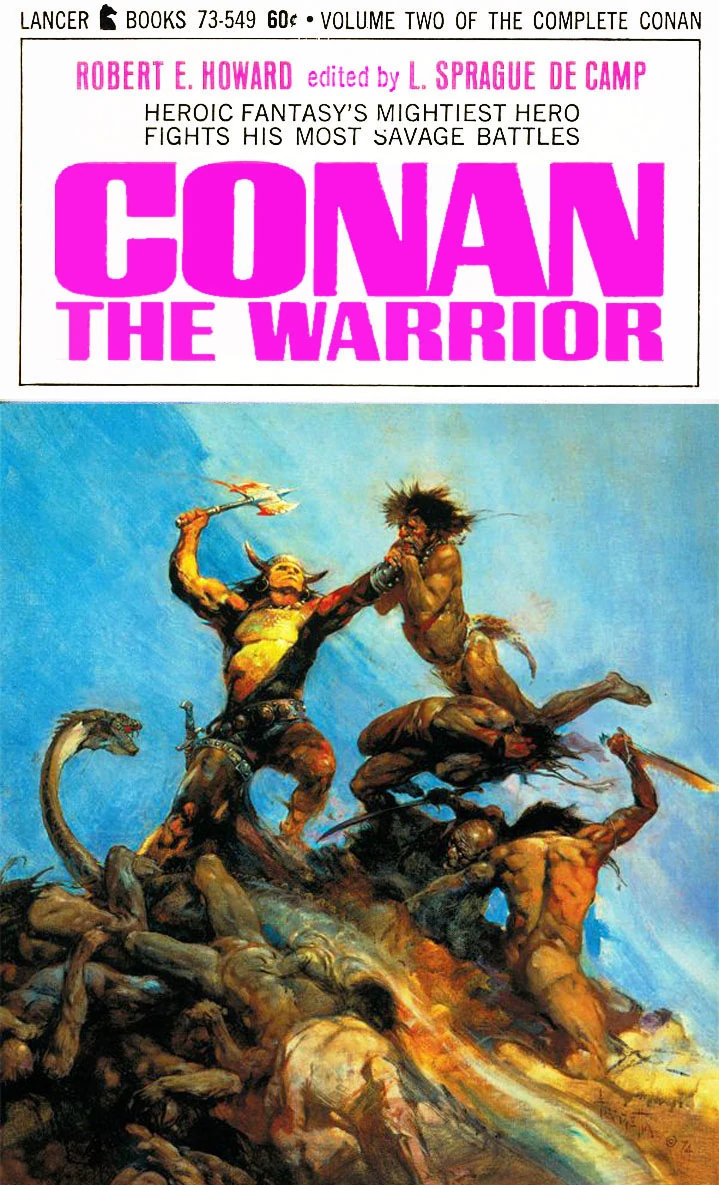

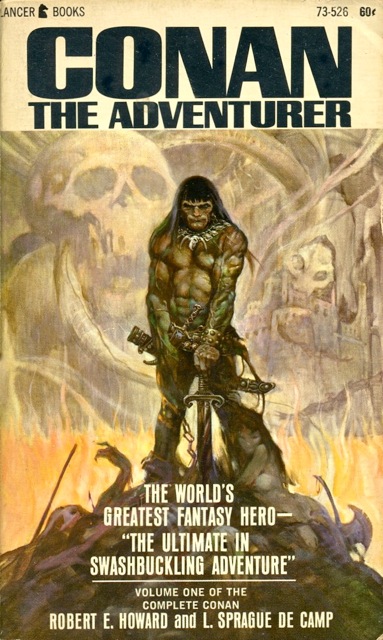

After Conan the Adventurer, which I reviewed last month for the Journey, I cracked open the purple edged pages of the follow-up collection Conan the Warrior with a mix of excitement and apprehension. For while I was happy to spend more time with the Cimmerian, I was also worried that this collection would be a let-down, compared to the high quality of the previous installment.

However, I need not have worried, because Conan the Warrior is even better than Conan the Adventurer, collecting one good and two excellent stories.

Red Nails

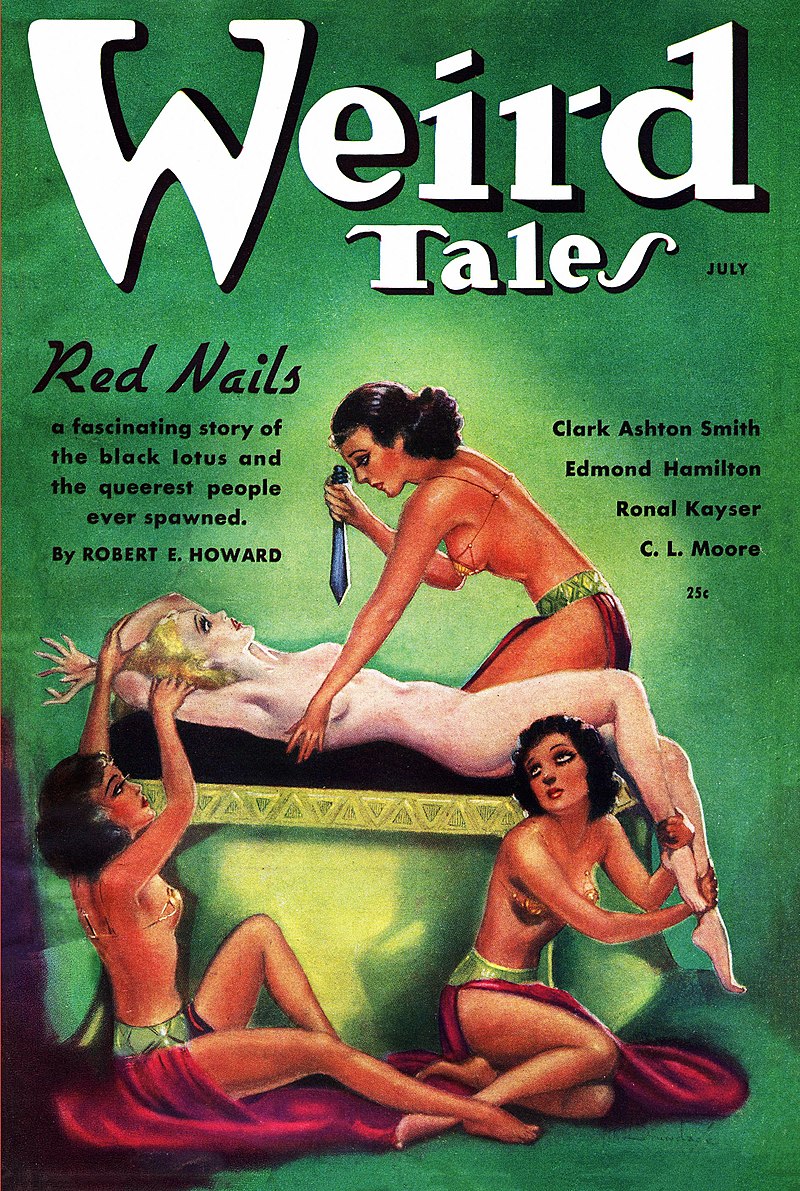

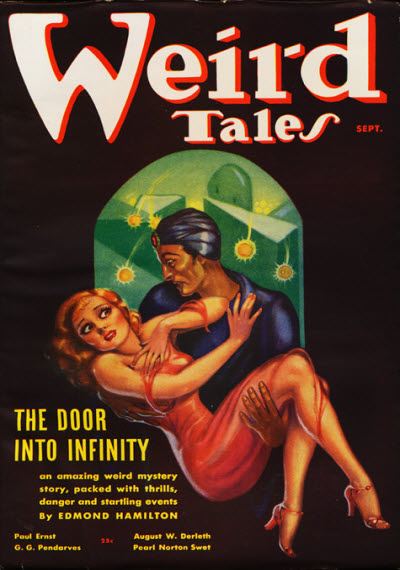

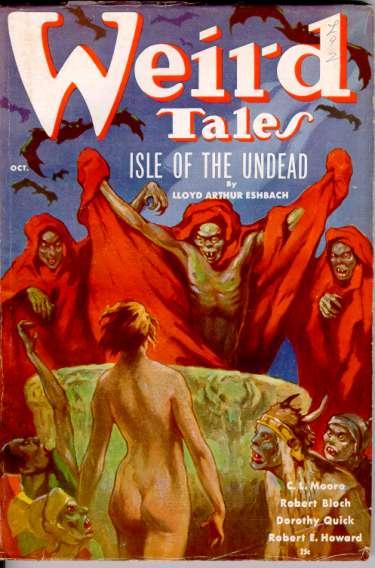

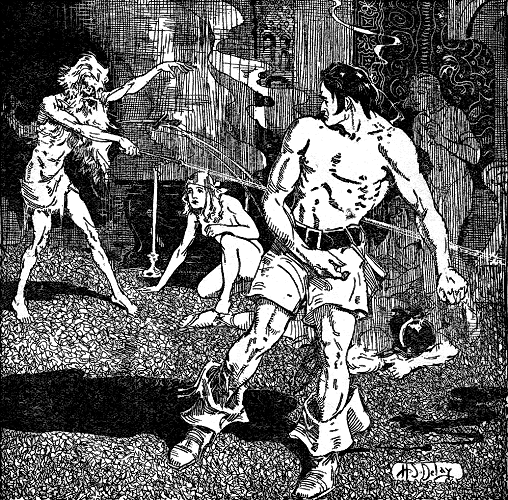

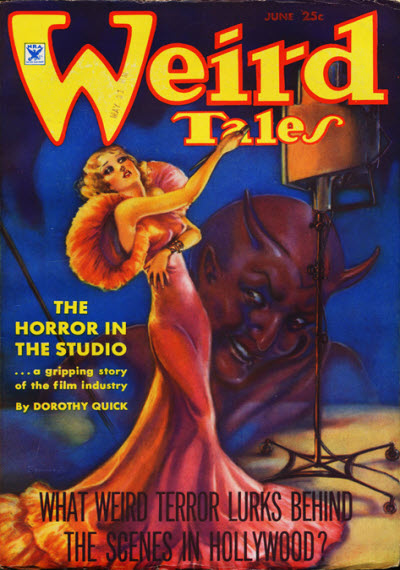

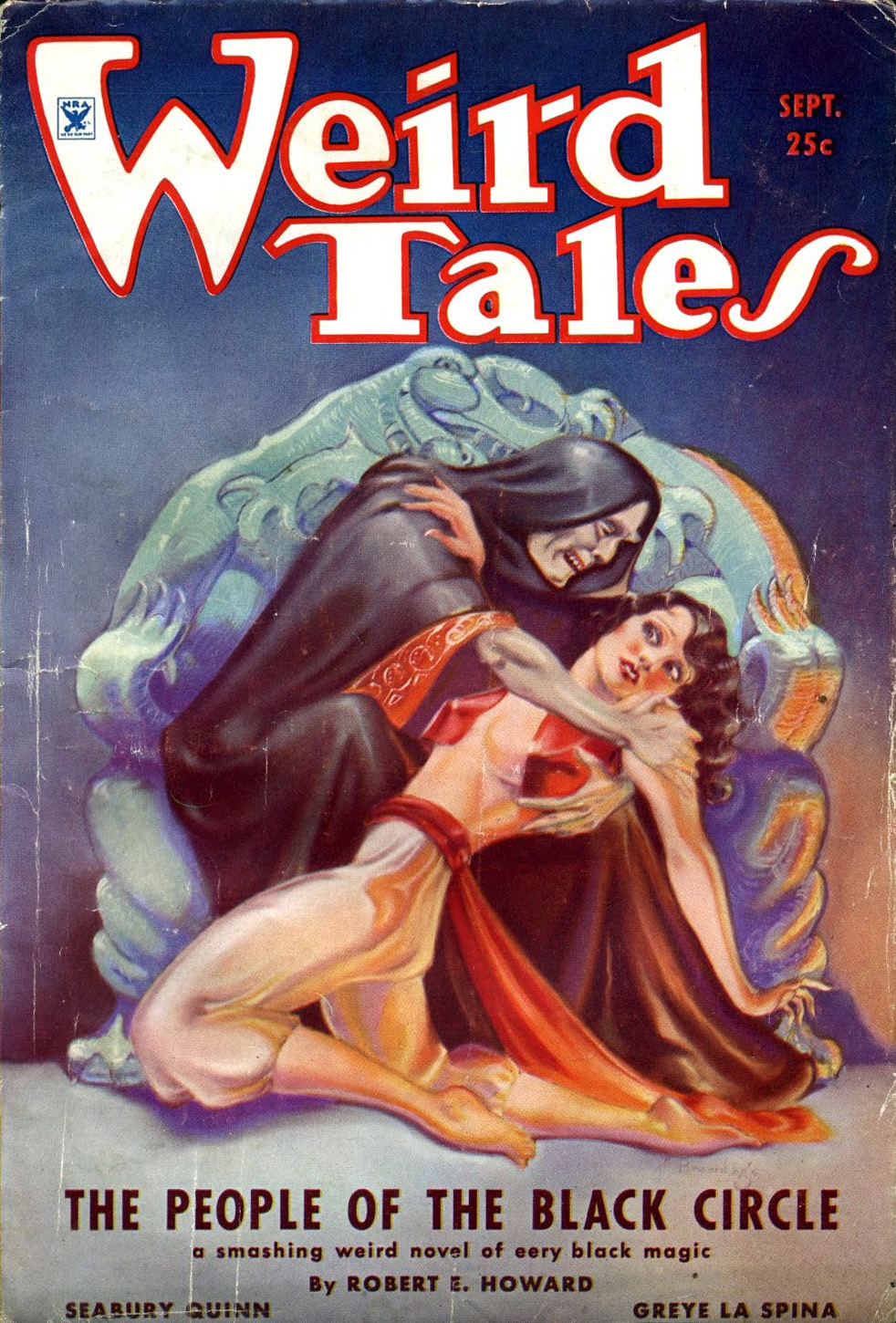

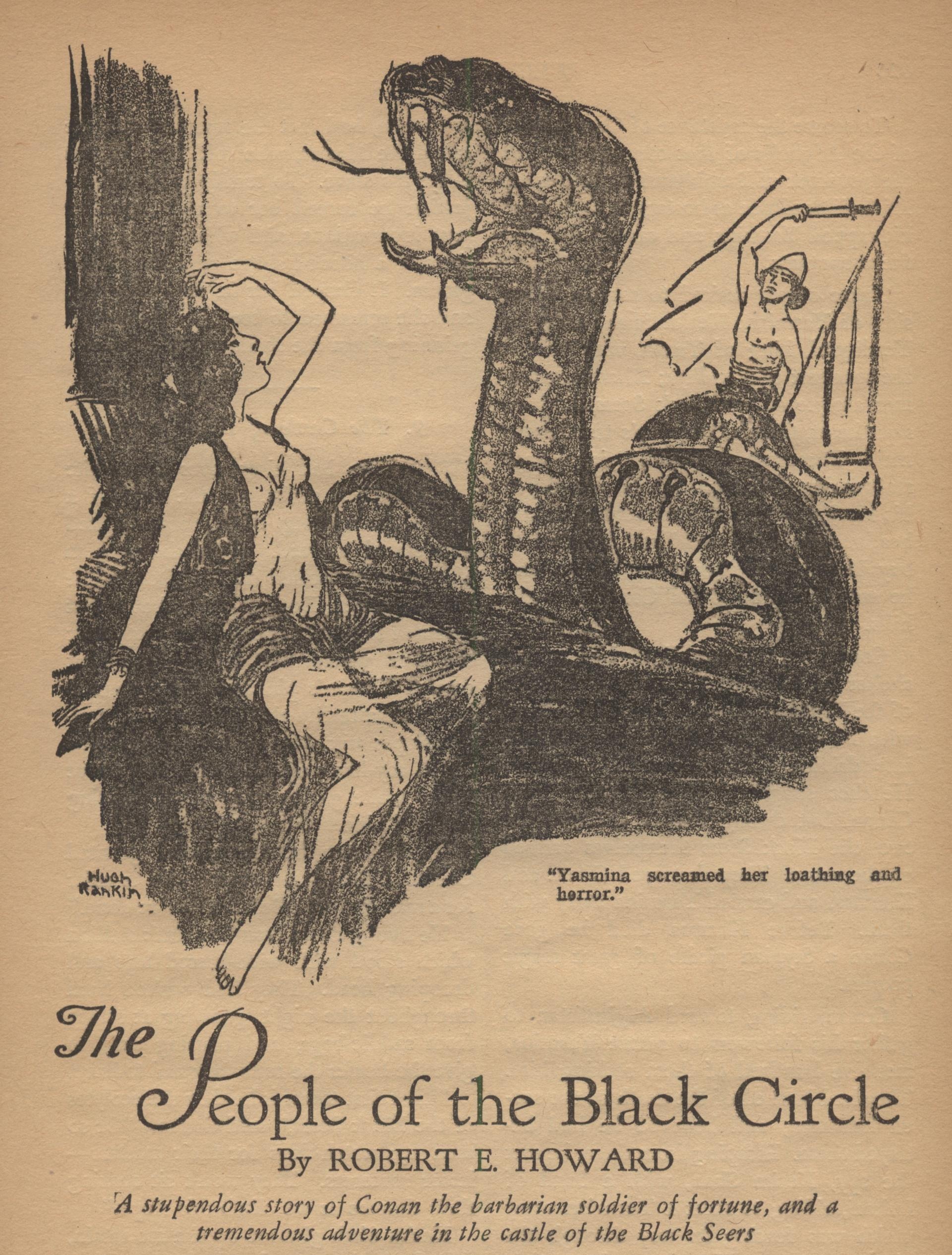

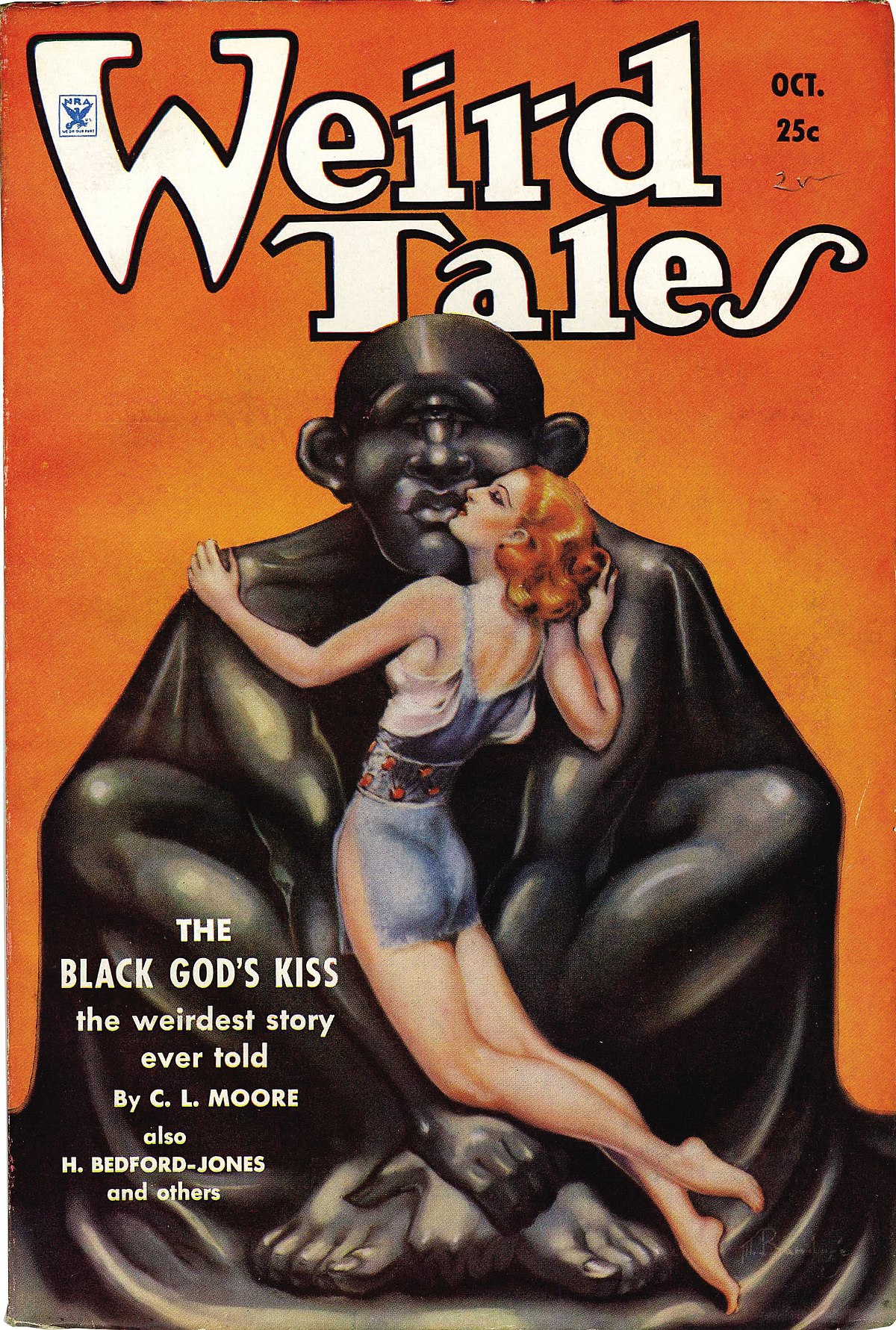

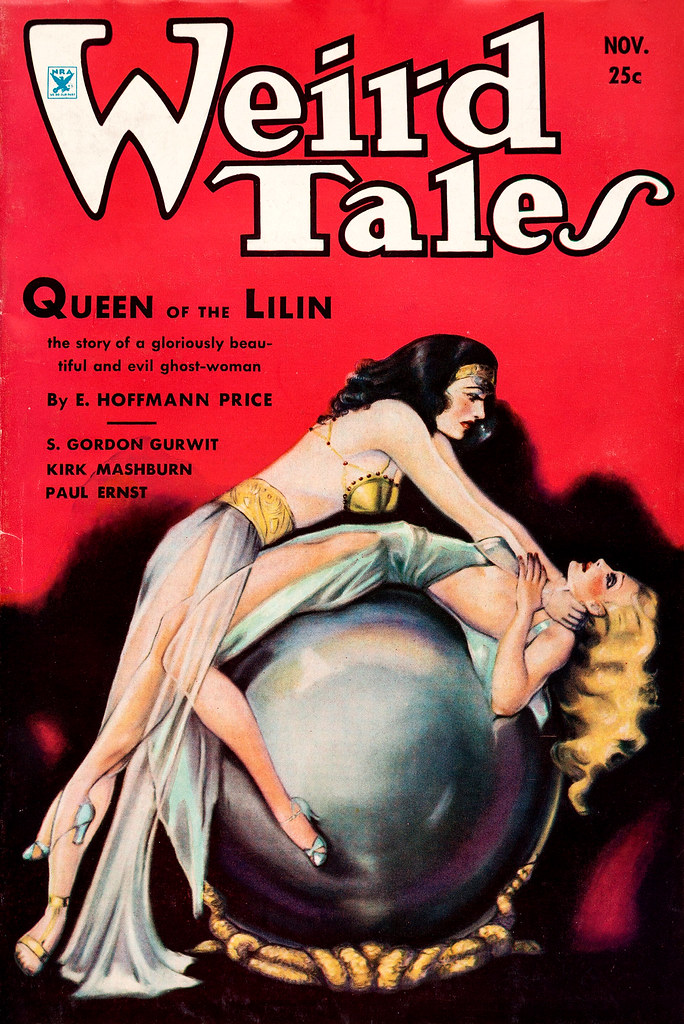

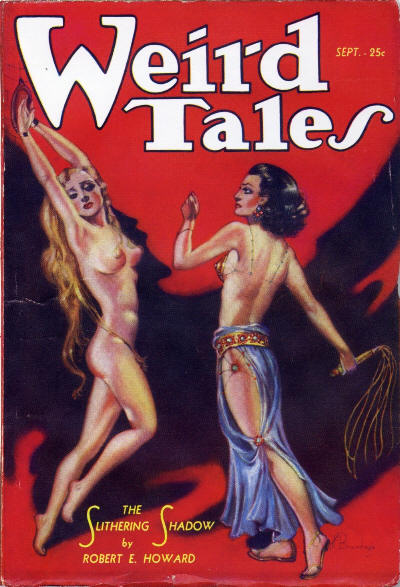

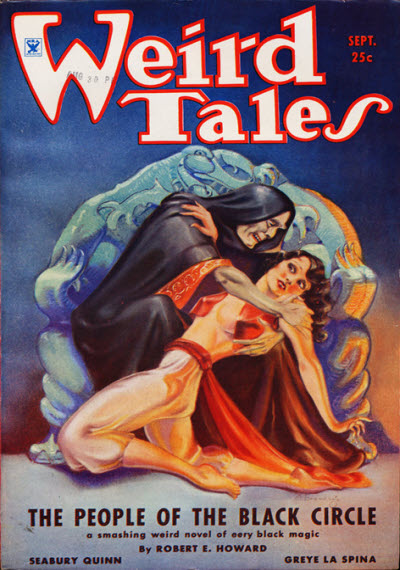

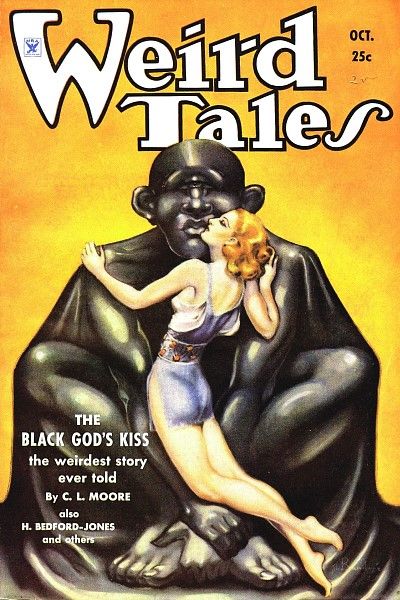

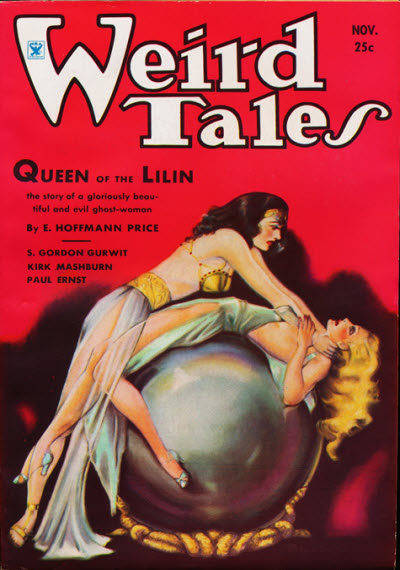

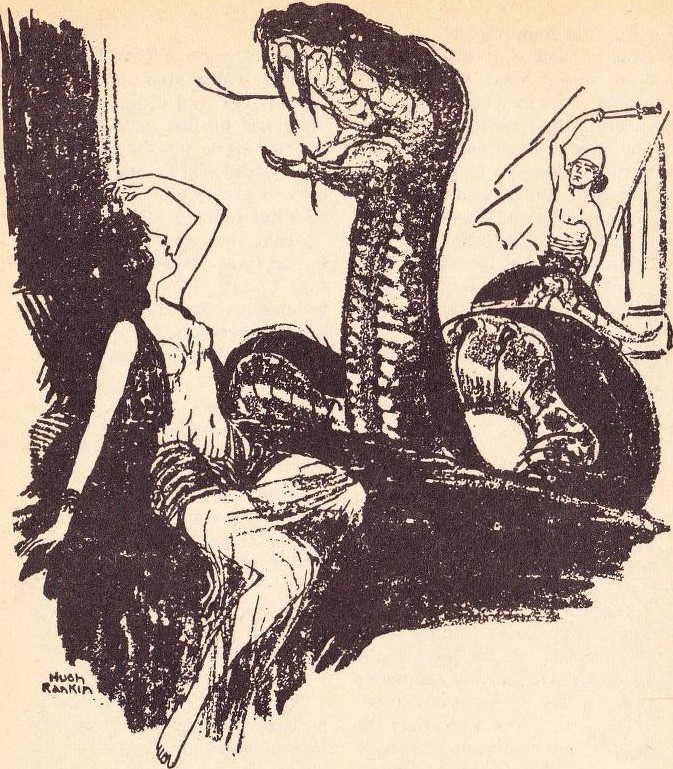

The novella "Red Nails" was serialised in Weird Tales from July to October 1936 and has the distinction of being the last Conan adventure that Robert E. Howard completed before his untimely death in 1936. And what an adventure it is.

Once again, the story opens not with Conan, but with another character, Valeria of the Red Brotherhood, a female pirate and mercenary, who had to go on the run when she killed an officer of the army in which she had enlisted, after he tried to rape her. Now Valeria makes her way through the uncharted jungles of the Hyborian Age equivalent of Africa. Unbeknownst to Valeria, Conan, who served in the same mercenary army, has fallen for Valeria and followed her into the jungle, quietly dispatching any other pursuers.

Valeria is a marvellous character, a warrior woman who is Conan's equal in many ways. "Why won't men let me live a man's life?" Valeria laments at one point. "That's obvious," Conan replies with an appreciative look at Valeria's body. Robert E. Howard is usually considered a writer of masculine fiction and Conan is clearly a man's man, but I was pleasantly surprised by the variety and competence of the female characters in these stories. Not every women in these stories is as impressive as Valeria or Yasmina from "The People of the Black Circle", but they are all characters with personalities and lives of their own and every one of them is given a chance to shine.

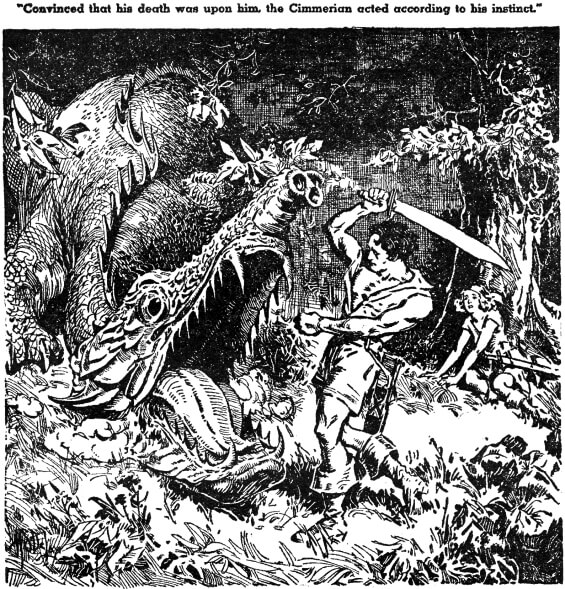

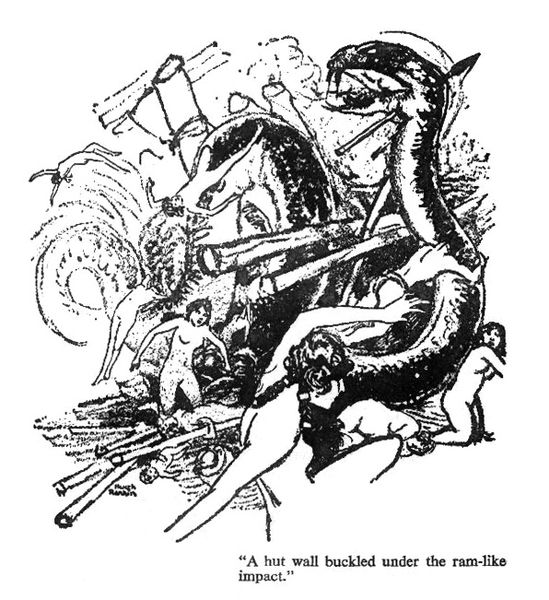

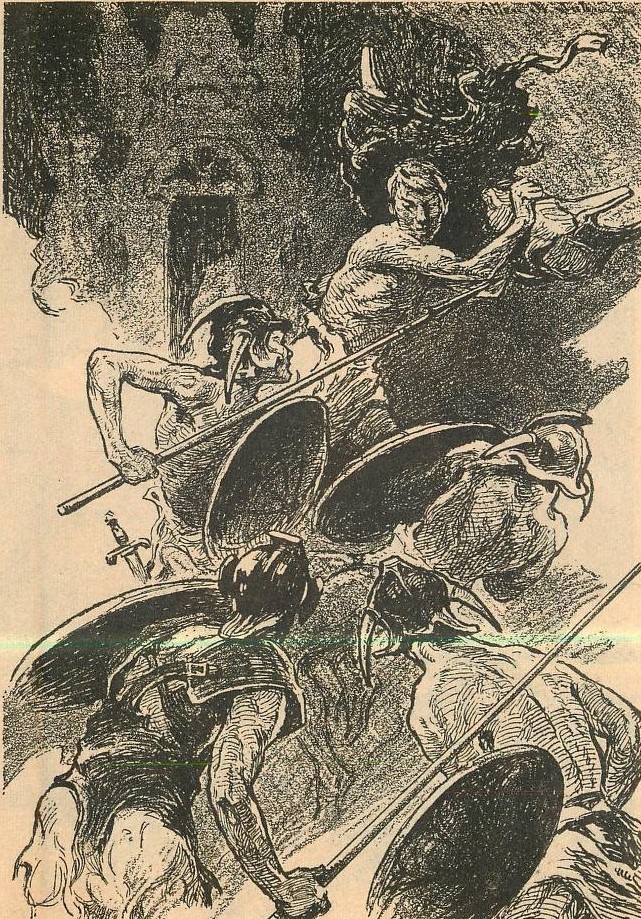

At first, Valeria is not too pleased to see Conan, but this quickly changes when Valeria and Conan find themselves pursued by what they call a dragon, but which twentieth century readers will quickly recognise as a dinosaur who has survived the extinction of its brethren. Now I was not expecting to see Conan and Valeria fighting a dinosaur, but my inner ten-year-old who loved dinosaurs was delighted.

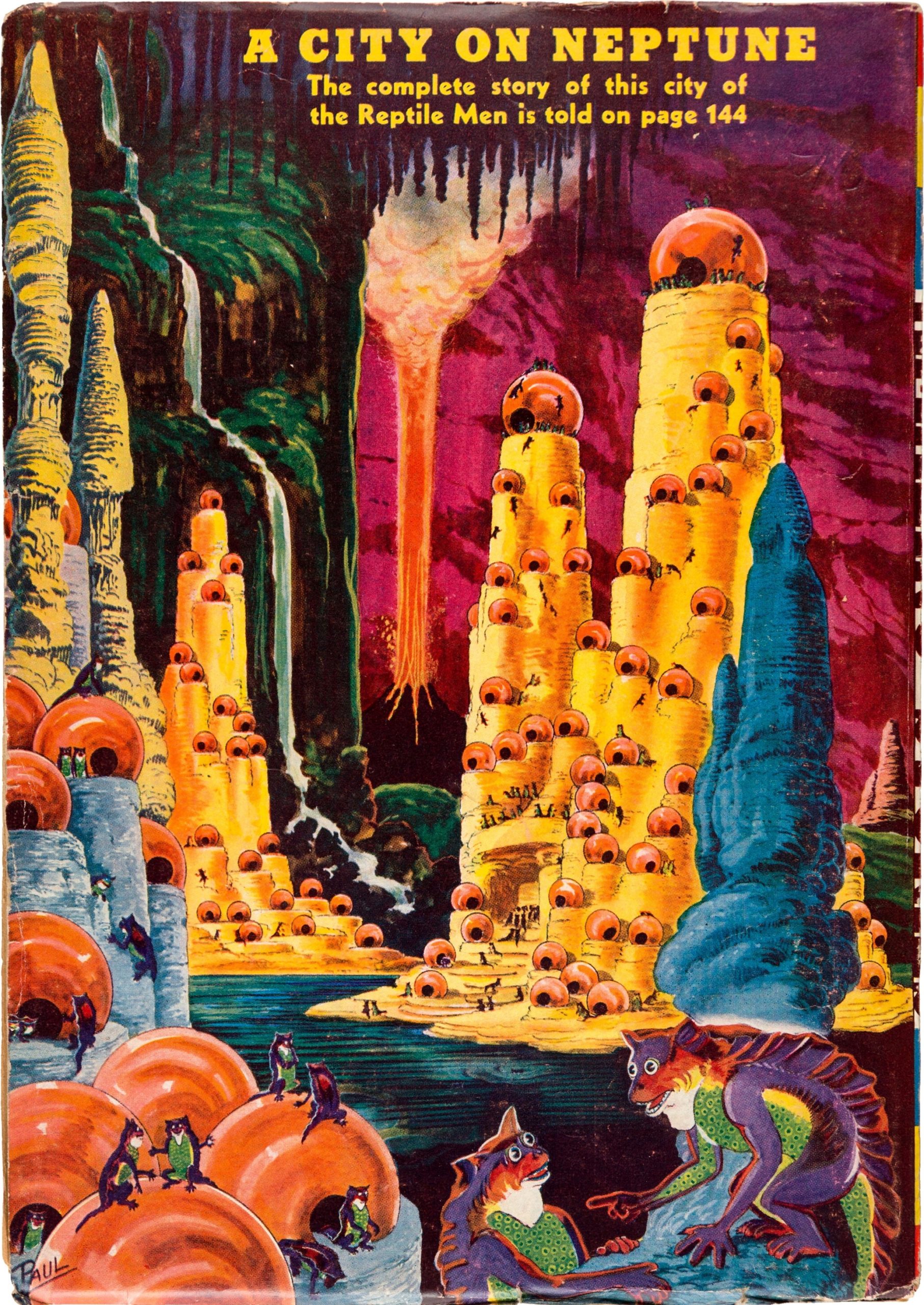

Together, Conan and Valeria manage to kill the dinosaur, but fearing there might be more in the jungle, they flee into the desert, where they spot yet another mysterious and seemingly abandoned city on the horizon. However, Xuchotl, which is not so much a city but a giant enclosed maze, is far from abandoned. Instead, it is home to two rivalling factions who are engaged in a generations long blood feud to the exclusion of all else. The title refers not, as I had initially assumed, to women's fingernails, but to copper nails which are hammered into a column to keep a tally of enemies killed.

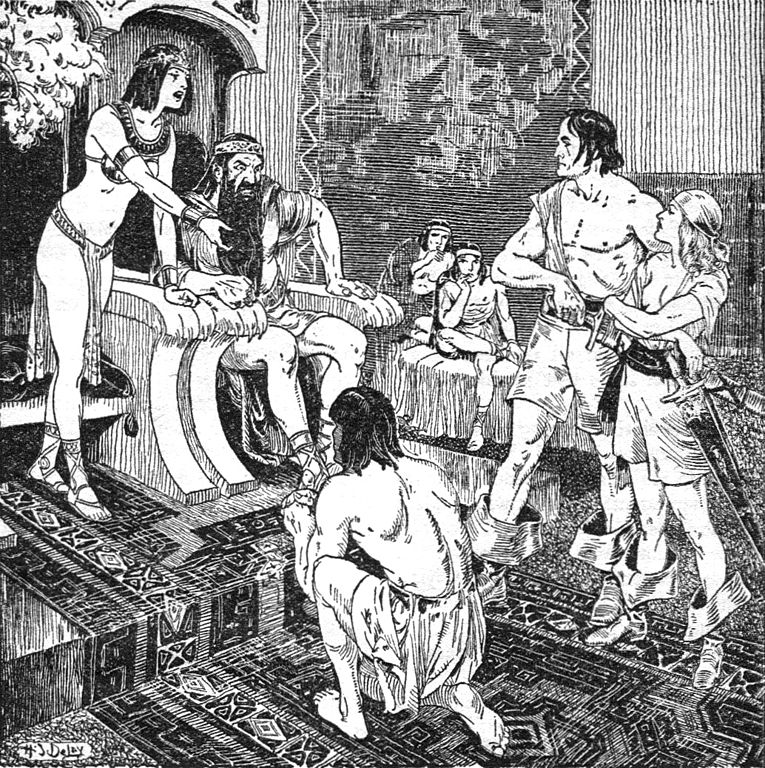

In spite of their best efforts, Conan and Valeria cannot avoid getting dragged into that feud. But other dangers lurk in Xuchotl as well, including a treacherous king, a vampiric queen with an unsavoury interest in Valeria and a mad sorcerer.

Robert E. Howard clearly enjoyed writing stories about mysterious cities in the desert inhabited by drugged out or otherwise insane inhabitants and monsters both human and supernatural, since no less than five of the seven stories in these collections include a variation on this theme. "Red Nails" is the best of these and it almost seems as if the previous stories were practice runs for this one.

Howard also contrasts the madness and inhumanity of Xuchotl's inhabitants and their endless feud with the warmth and humanity of both Conan and Valeria. There is a wonderful moment where Conan's interrupts the pompous King Olmec's victory speech with a gruff "You'd best see to your wounded." We also see Conan and Valeria taking care of each other and treating each other's injuries. Fantasy fiction rarely pays attention to the physical cost of battle, but the Conan stories repeatedly show that characters, including Conan, can and will be wounded. Robert E. Howard's father was a Texas country doctor, so Howard knew a thing or two about injuries.

Another amazing (and very bloody) adventure with a heroine who's Conan's match in every way. Five stars.

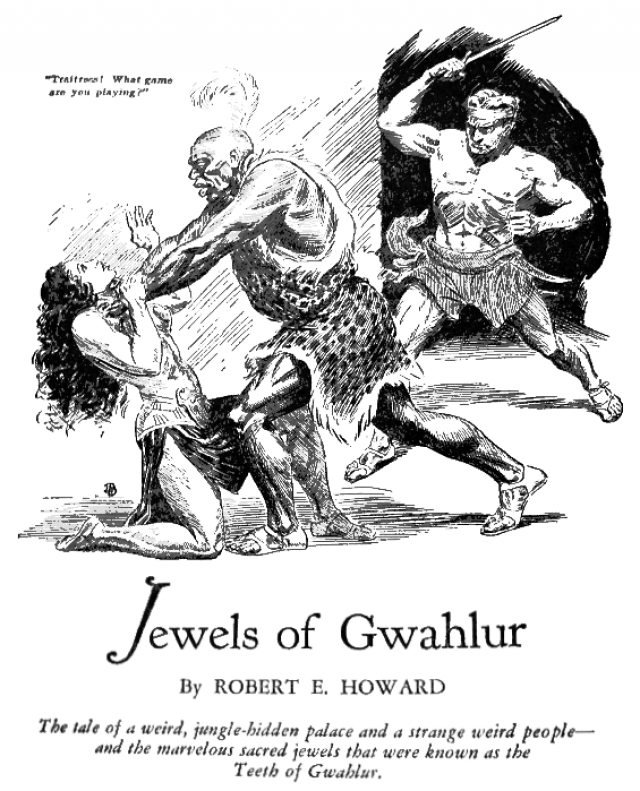

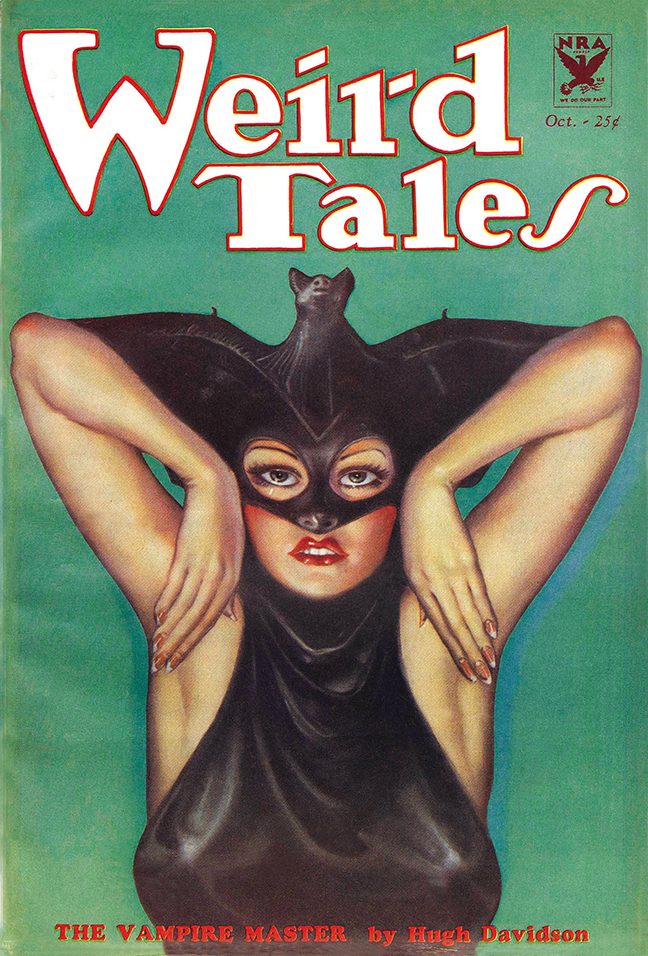

The Jewels of Gwahlur

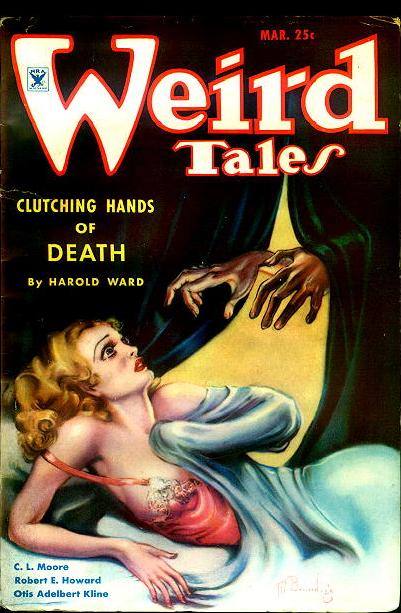

This novelette appeared in the March 1935 issue of Weird Tales and finds Conan still (or once again) in Africa, climbing the sheer walls of a cliff surrounding the ruined city of Alkmeenon. Inside this city, there rests a legendary treasure of priceless jewels known as the Teeth of Gwahlur.

Conan is eager to get his hands on this treasure and has ingratiated himself with the King of Keshan in order to steal the jewels, which happen to be sacred to the people of Keshan.

However, Conan isn't the only one who's after the jewels. There's also his rival Thutmekri and his accomplice, the fake oracle Muriela. Furthermore, the city of Alkmeenon once again is not nearly as deserted as everybody believes, but is still being stalked by the monstrous servants of its former masters.

So far in this collection, we've seen Conan the mercenary, Conan the warlord and Conan the pirate. This story adds a new dimension to the Cimmerian and gives us Conan the con man, who is literally running a long con to get his hands on the jewels. The city of Alkmeenon, located in the center of what a modern reader will recognise as an extinct volcano, is a very evocative setting. Though unfortunately, the descriptions of the black characters who appear in the story are once again dated and no longer appropriate to the civil rights era. The heroine Muriela is no Valeria either, but closer to the stereotype of the clinging and whimpering damsel.

A fun heist story starring Conan. Four stars.

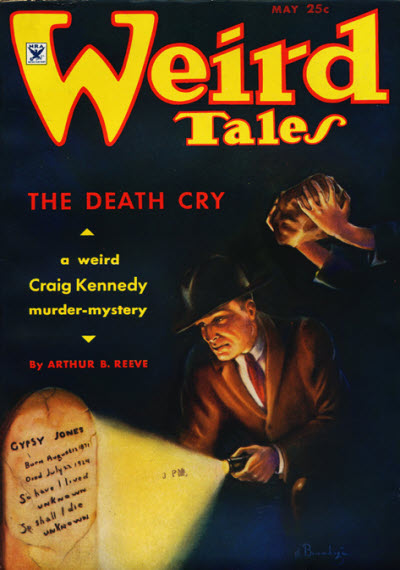

Beyond the Black River

This novella was originally serialised in the May and June 1935 of Weird Tales and is set on the northern edge of Aquilonia, the Hyborian age equivalent of France and also the kingdom Conan will eventually come to rule. Aquilonia has recently expanded its borders northwards into the wilderness inhabited by the barbarian Picts. The Picts are understandably not happy about this.

The historical Picts were a people who lived in what is now Scotland during the late Roman era and the early Middle Ages. Little is known about them and so Howard uses a lot of poetic licence to turn his version of the Picts into analogues for American Indians, setting up a frontier conflict. The Picts are very much depicted as offensive stereotypes here, though Howard also wrote several stories chronicling the struggles of a Pictish chieftain named Bran Mak Morn with the Roman Empire, where the Picts are portrayed in far more sympathetic light.

Once again, the novella opens not with Conan, but with a young man named Balthus who has come to Aquilonia's newly opened frontier, lured by promises of cheap and abundant land. However, Balthus quickly encounters the Picts and is saved by none other than Conan, who has come to Fort Tuscelan to serve as a mercenary. Since Conan's homeland Cimmeria borders on Pictish territory (though the Cimmerians and the Picts are ancestral enemies), the Fort's commander puts Conan's wilderness skills and knowledge of the enemy to good use by sending him on scouting missions.

Conan is convinced that Aquilonia's expansion plans will eventually fail, when the various Pictish tribes rally together to kick out the invaders. After all, that was what the Cimmerians did when Aquilonia attempted to annex their territory. Balthus has heard stories of that legendary battle for the Aquilonian Fort Venarium and asks Conan if he was there. "Yes," Conan says and calmly tells Balthus that he fought on the Cimmerian side as a fifteen-year-old. So Conan fought the very people at the age of fifteen that he will come to rule as a king some twenty-five years later and sees absolutely no contradiction in this.

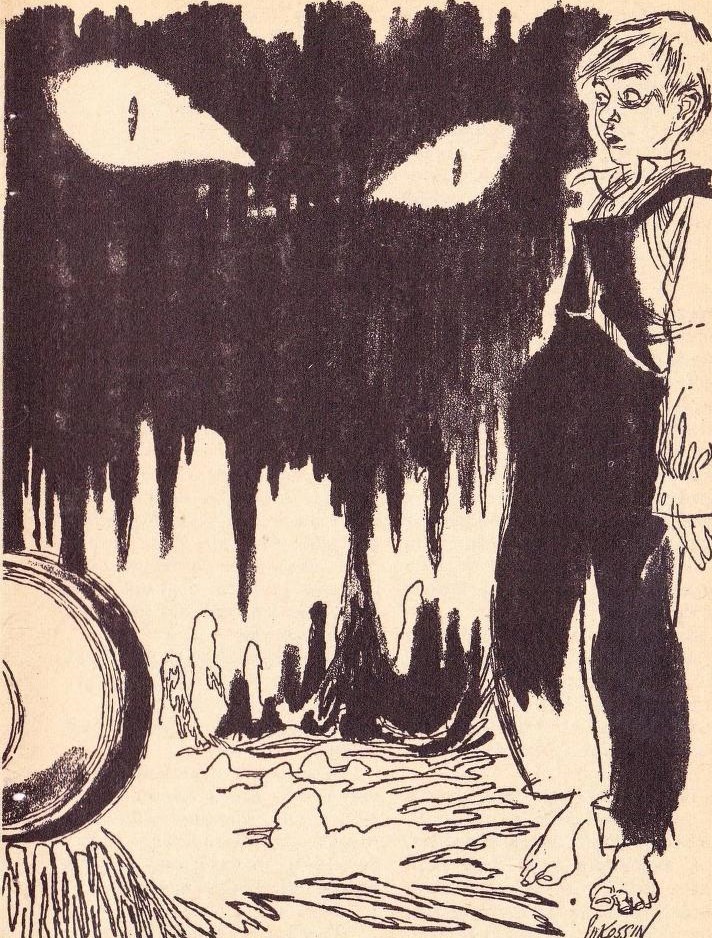

Conan's prediction proves to be accurate, for the Pictish wizard Zogar Sag has rallied the tribes and is gearing up for an assault on Fort Tuscelan. Conan and a party of scouts, including Balthus, sneak into Pictish territory to take out Zogar Sag. But they are ambushed and only Conan and Balthus survive. However, the attack on Fort Tuscelan has already begun and all Conan and Balthus can do is to warn the Aquilonian settlers, so they can flee before they are slaughtered.

Of all the Conan stories I've read so far, this one is the bleakest, since it literally ends with everybody except for Conan dead. This includes Balthus who makes a heroic last stand together with a feral dog named Slasher to allow the settlers to escape to safety.

Now I'm very much not a dog person and Slasher, who went feral after the Picts murdered his owner and now takes revenge on the slayers in his own fashion, is very reminiscent of the slobbering and barking menaces that chased after me behind much too low fences when I rode my bicycle to school as a kid. That said, Slasher is a marvellous character in his own right and the mix of total savagery towards the Picts and affection towards Balthus rings so true that I wonder if Howard owned a dog. I'm not someone who cries at movies or books and managed to sit through all of Doctor Zhivago without shedding a single tear. However, the heroic sacrifice of Slasher and Balthus made even me misty-eyed.

"Beyond the Black River" also showcases Howard's versatility, since he plops Conan into what is basically a western. And considering Howard grew up in Texas at a time when the so-called Old West was still within living memory, it seems only natural that he would draw on the frontier era in his fiction.

To someone from West Germany, the Old West is just as exotic as the Hyborian Age. Nonetheless, I connected to this story, because I noticed many parallels between the Cimmerians and later the Picts kicking the Aquilonians out of their respective homelands and my own ancestors, led by the Cherusci chieftain Arminius, kicking the Romans out of Northern Germany in the battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.

"Beyond the Black River" also ends with what is probably one of Howard's most famous lines: "Barbarism is the natural state of mankind. Civilization is unnatural; it is a whim of circumstance… And barbarism must always ultimately triumph!"

A bleak and grim story that will stick in your mind for a long time. Five stars.

A Multi-faceted Barbarian

So far, I have read a few of the Conan stories in scattered reprints in magazines and collections as well as two of Lancer's new paperback collections and I'm struck by the variety of settings and themes in the stories that Robert E. Howard wrote about this character. But even though the various stories reveal different aspects of the Cimmerian, Conan always remains recognisably the same character.

Those who have heard of Conan, but have not read the actual stories featuring him, inevitably cite Conan's violence, his physical strength and his womanising as his most notable characteristics. Nor are they wrong, because Conan is clearly a violent man. Those at the receiving end of his sword or his fists usually deserve their fate, but it's also difficult to overlook that Conan outright murders the pirate captain Zaparavo in "Pool of the Black One" to take over his ship and also murders a rival in "Drums of Tombalku" to usurp his position.

A lot of people also think that Conan is stupid, an illiterate Barbarian, big of muscle and small of brain. They could not be more wrong, because the Conan depicted by Robert E. Howard is actually a very intelligent man. He speaks, reads and writes multiple languages. He is a also a brilliant military strategist and tactician and – at least in "The Jewels of Gwalhur" – a clever con man.

As for the womanising, like many men, Conan does think with the dangly bit on occasion. In "Red Nails", Conan literally walks across half a continent in order to go after and protect the woman he has fallen for.

In the seven stories collected in Conan the Adventurer and Conan the Warrior, Conan is without female companionship in two of the stories and with a different woman in the each of the remaining five. And even though most Conan stories end with Conan walking off into the sunset with his current lover, the woman in question is usually nowhere to be seen in the following story. This is a pity, for while some of the female characters in these stories are insipid non-entities like the woman clinging to Conan's leg on Frank Frazetta's cover for Conan the Adventurer, Conan is also paired with some remarkably strong women like Valeria from "Red Nails" or Yasmina from "People of the Black Circle".

But then, Conan is extremely charismatic. He may be a loner and wandering outlaw for much of his career, but Conan never has problems persuading people to follow him. In "Drums of Tombalku", Conan goes from prisoner marked for death to leader of the warriors who have captured him within the space of a few days. And in "Pool of the Black One", Conan steals the crew of the pirate captain Zaparavo from under his nose by gaining their loyalty. Even though those stories haven't been reprinted yet, it's easy to see how Conan will wind up becoming King of Aquilonia, the very country whose warriors he helped to kick out of his native Cimmeria at the age of fifteen.

Though for Conan, loyalty is not a one way street. In fact, the most notable of Conan's traits that appears in story after story is his deep loyalty towards friends, lovers, comrades in arms and people he feels responsible for. In "People of the Black Circle", Conan's main goal throughout the story is freeing the seven of his men who have been captured by the authorities of Vendya. Nor will Conan abandon the people he has adopted, even after they try to kill him. And when one of his friends is killed, as happens in "Drums of Tombalku" and "Beyond the Black River", Conan swears bloody vengeance on the killers.

Closely linked to Conan's deep loyalty towards people he feels responsible for is a trait that is not often brought up in connection with a violent Barbarian warrior, namely his compassion. For these stories demonstrate again and again that Conan deeply cares about people, whether it is his budding friendship with Balthus and Slasher in "Beyond the Black River", his protectiveness towards Valeria in "Red Nails" or Conan freely foregoing the great treasure he has been chasing after for the entire story in order to save a life at the end of "The Jewels of Gwalhur". Indeed, it is when pitted against a merciless and utterly inhuman opponent, whether it's the wizards of Mount Yimsha in "People of the Black Circle", the blood-mad inhabitants of Xuchotl in "Red Nails", the apathetic pleasure seekers of Xuthal in "The Slithering Shadows" or the murderous Pictish warriors and wizards in "Beyond the Black River", that Conan's humanity shines most brightly.

Now that Lancer is reprinting all the stories, you owe it to yourself to get to know the real Conan, this fascinating and multi-faceted character that Robert E. Howard created more than thirty years ago.

Three fabulous tales of the Cimmerian Barbarian. Five stars for the collection.

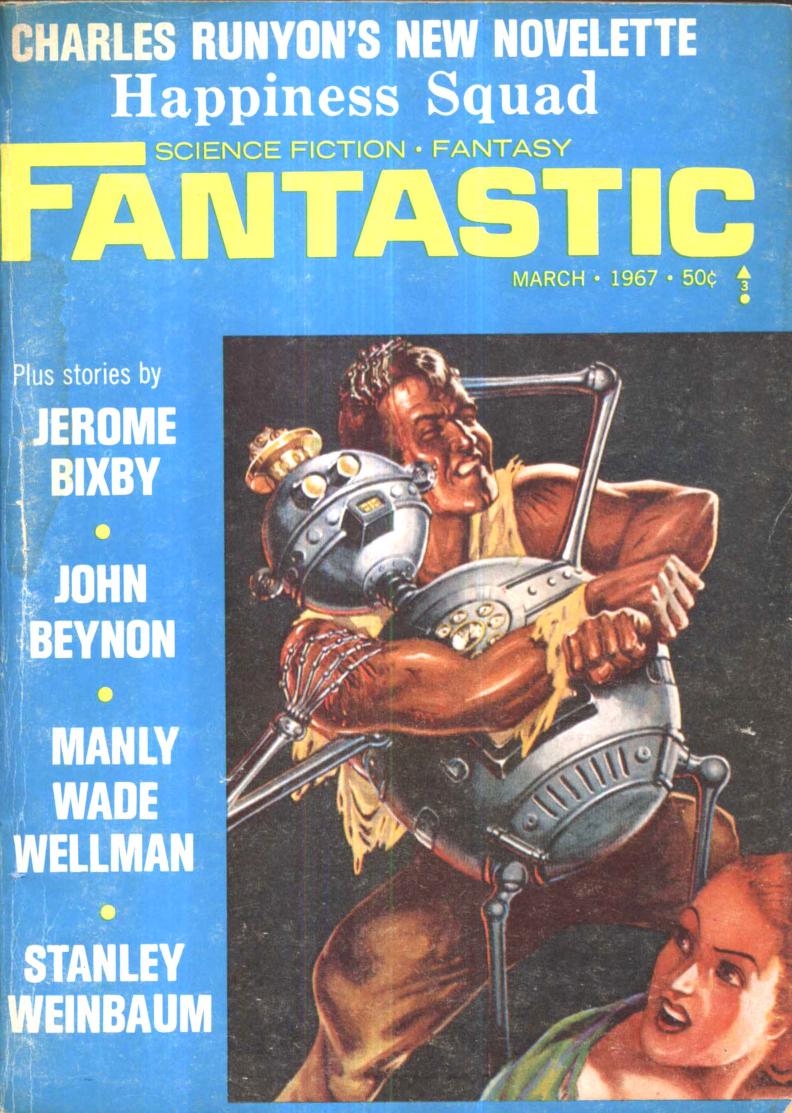

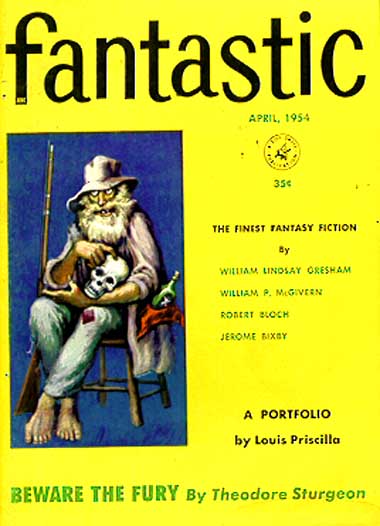

![[February 12, 1967] All's Fair in Love and War (March 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Fantastic_v16n04_1967-03_LennyS-cape1736_0000-2-672x324.jpg)

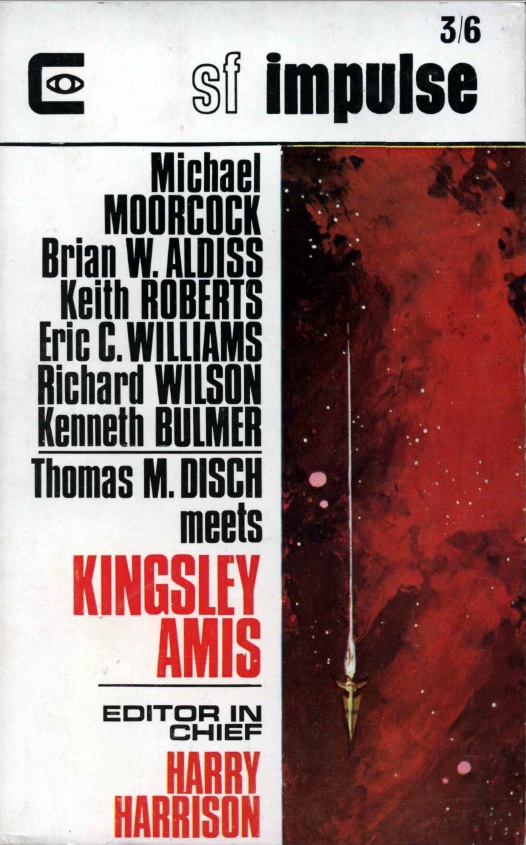

![[January 24, 1967] Absenteeism and Making Do <i>SF Impulse</i>, February 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/SF-Impulse-Jan-67-672x372.jpg)

![[January 22, 1967] The Return of the Cimmerian: <i>Conan the Adventurer</i> by Robert E. Howard](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/14539434635_ea7488eae9_o-672x372.jpg)

![[December 28, 1966] Ice Worlds, Telepathic Martian Mice and Echoes (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, January 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/New-Worlds-Impulse-Jan-67-1-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[December 8, 1966] Flesh and Blood (January 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Fantastic_v16n03_1967-01_0001-4-672x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1966] White Boats, Whales and Disch, <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, December 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Dec-1966-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by Unknown Artist

Illustration by Unknown Artist

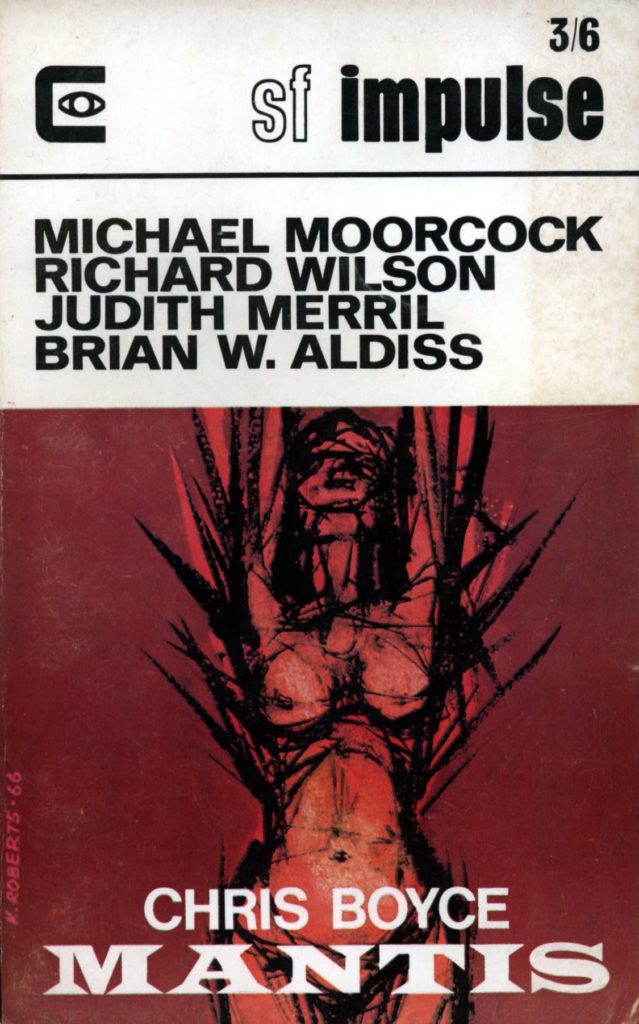

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[October 24, 1966] Birds, Roaches and Rings, <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, November 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-November-66-672x372.jpg)

![[October 16, 1966] Only the Lonely (November 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/fantastic_196611-3.jpg)

![[September 28, 1966] Garbage and Aliens (October 1966 <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)