by David Levinson

A paper dragon

Back in April, I wrote about a border skirmish between the Soviet Union and China. That wasn’t the end of the matter. The Soviets went on a minor diplomatic offensive, trying to get India to join an alliance against China and to pull North Korea back into the Soviet orbit. Violence flared up again in August on the Terekty River on the border between the Sinkiang region of China and the Kazakh SSR. As in April, both sides accused the other of crossing the border.

Rumor has it that Soviet Foreign Minister Alexei Kosygin attempted to contact the Chinese government in an effort to calm tensions and reopen negotiations on the border. His efforts were reportedly rudely rebuffed by Chairman Mao. At the funeral of Ho Chi Minh in early September, the Soviet and Chinese delegations went out of their way to avoid being in the same room with each other, even attending the funeral at different times.

When Kosygin left Hanoi on September 11th, his plane was denied entry into Chinese airspace, forcing a long detour. But while the plane was refueling in India, Kosygin was informed that the Chinese were ready to talk. He promptly flew to Peking, where he and Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai met at the airport. They agreed to reinstate diplomatic relations and reopen talks on the border.

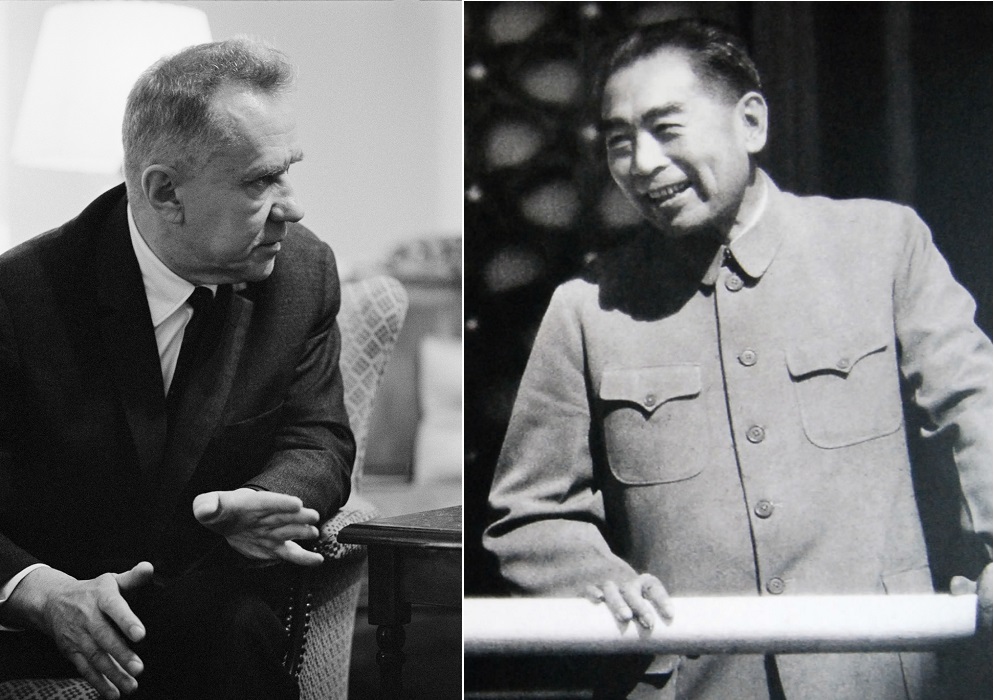

l. Soviet Foreign Minister Alexei Kosygin, r. Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai

l. Soviet Foreign Minister Alexei Kosygin, r. Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai

Despite that, Mao continued to ramp up his hostile rhetoric towards the Soviets. China also began moving large numbers of troops north to the border regions. That was followed by two unannounced nuclear tests at the end of September, most notably China’s largest detonation to date (3 megatons) on the 29th. The very next day, Chinese Defense Minister Lin Biao put the armed forces on the highest level of alert.

And then on October 9th, Mao blinked. China announced that they would no longer claim territory annexed by Tsarist Russia over the last 300 years through “unequal treaties.” The only concession demanded is that the Soviet Union acknowledge that the treaties were unfair. The status quo has been restored, and the only result of six months of high tension is several ulcers and a huge sigh of relief around the world.

Love among the ruins

Love runs through most of the stories in this month’s IF. Not as a romantic theme, but rather as an examination of the ways in which it affects the events of the stories and is in turn affected by events.

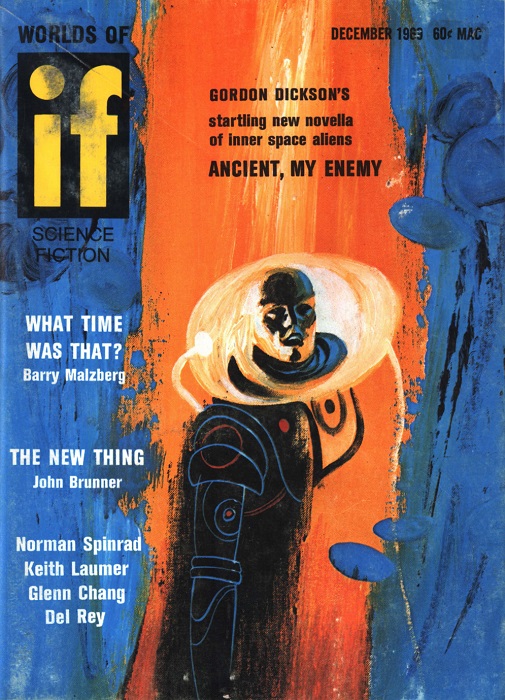

Vaguely suggested by Ancient, My Enemy. Art by Gaughan

Vaguely suggested by Ancient, My Enemy. Art by Gaughan

Continue reading [November 2, 1969] Love and Hate (December 1969 IF)

![[November 2, 1969] Love and Hate (December 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/IF-1969-12-Cover-505x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1969] There was a ship (November 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Venture-1969-11-Cover-480x372.jpg)

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage.

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage. Art by Tanner

Art by Tanner![[October 2, 1969] Darkness, Darkness (November 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IF-1969-11-Cover-503x372.jpg)

King Idris from a couple of years ago.

King Idris from a couple of years ago. Libya’s new Prime Minister, Soliman Al Maghreby.

Libya’s new Prime Minister, Soliman Al Maghreby. This month’s cover depicts nothing in particular. Art by Gaughan

This month’s cover depicts nothing in particular. Art by Gaughan![[September 4, 1969] <i>Plus ça change</i> (October 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/IF-1969-10-Cover-487x372.jpg)

Penelope Ashe, in part, with the cover model superimposed.

Penelope Ashe, in part, with the cover model superimposed.

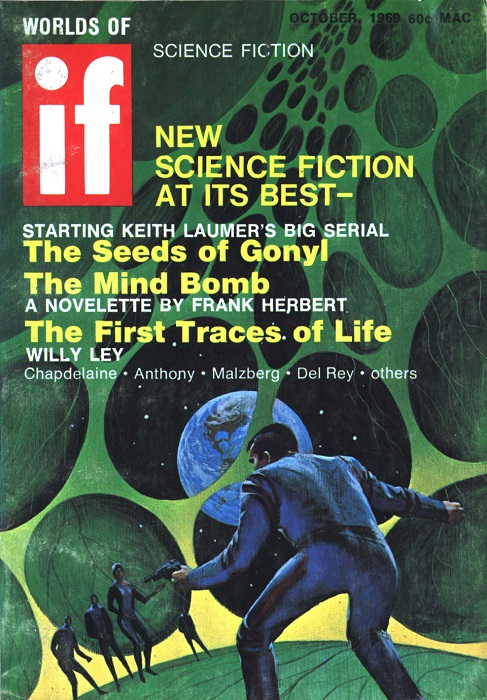

Supposedly for Seeds of Gonyl. If so, it’s from later in the novel. Art by Gaughan

Supposedly for Seeds of Gonyl. If so, it’s from later in the novel. Art by Gaughan![[August 2, 1969] Specters of the past (September 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/IF-1969-09-Cover-494x372.jpg)

Salvadoran President and General Fidel Sanchez Hernandez inspecting the troops.

Salvadoran President and General Fidel Sanchez Hernandez inspecting the troops. A robot carrying off a fainting human woman. It’s not as old-fashioned as you might think. Art by Chaffee

A robot carrying off a fainting human woman. It’s not as old-fashioned as you might think. Art by Chaffee![[July 2, 1969] Merging streams (August 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Venture-1969-08-Cover-543x372.jpg)

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner![[June 2, 1969] The ever-whirling wheel (July 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IF-1969-07-Cover-495x372.jpg)

Art credited only as couresy of Three Lions, Inc. but actually by German artist Johnny Bruck.

Art credited only as couresy of Three Lions, Inc. but actually by German artist Johnny Bruck.![[April 12, 1969] A New Venture (May 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Venture-1969-05-Cover-494x372.jpg)

The first and last covers for the first run of Venture. Art in both by Ed Emshwiller

The first and last covers for the first run of Venture. Art in both by Ed Emshwiller This singularly unattractive cover is by Bert Tanner.

This singularly unattractive cover is by Bert Tanner.![[April 6, 1969] The Weight of History (May 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IF-1969-04-Cover-500x372.jpg)

A map showing the location of Chenpao/Damansky Island

A map showing the location of Chenpao/Damansky Island Chinese soldiers pose with their captured Russian tank

Chinese soldiers pose with their captured Russian tank The cover illustrates Groovyland and is credited as courtesy of Three Lions, Inc., but see below

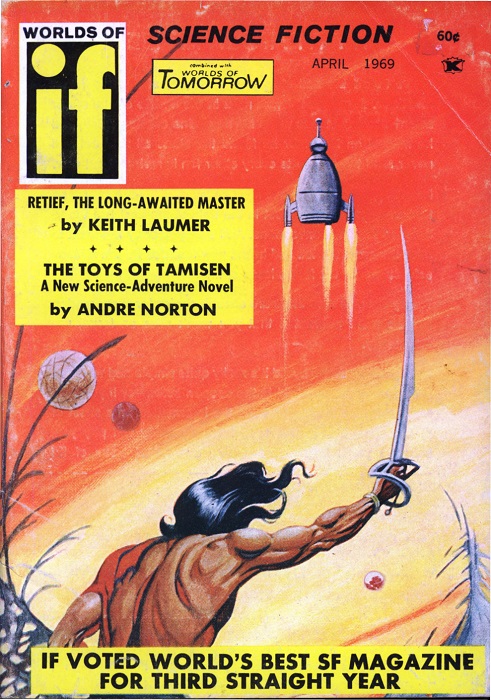

The cover illustrates Groovyland and is credited as courtesy of Three Lions, Inc., but see below![[March 2, 1969] Dreams and reality (April 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/IF-1969-04-Cover-491x372.jpg)

Ayub Khan greets LBJ in Karachi in 1967.

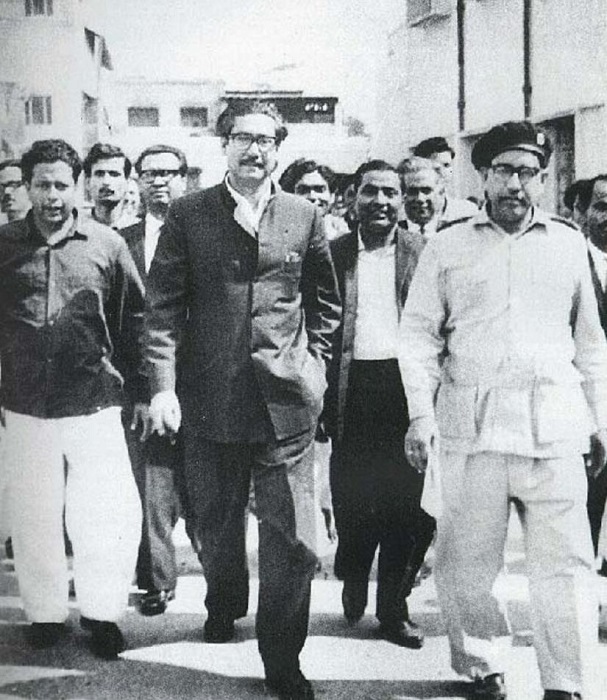

Ayub Khan greets LBJ in Karachi in 1967. Sheikh Mujib (center) emerges from prison.

Sheikh Mujib (center) emerges from prison. Like I said, swords and spaceships. Art by Adkins

Like I said, swords and spaceships. Art by Adkins