by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

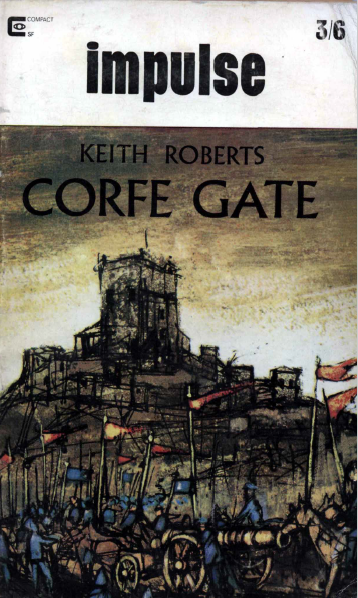

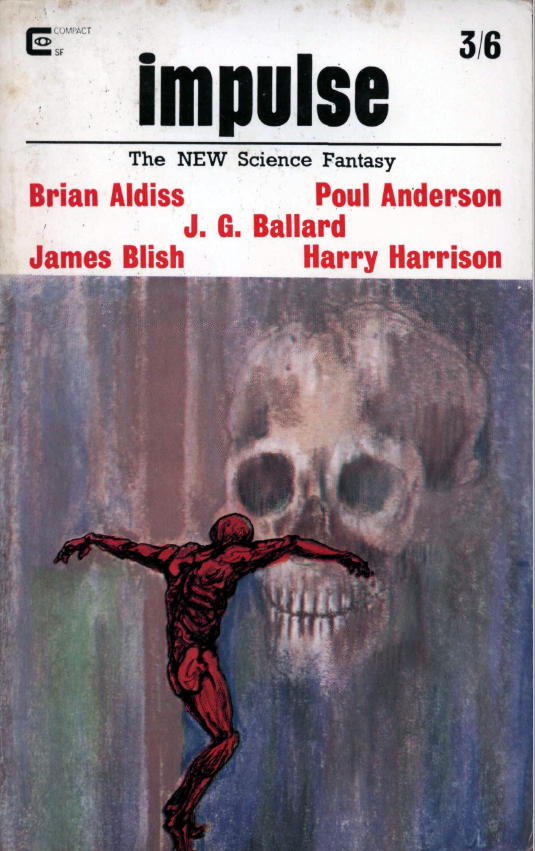

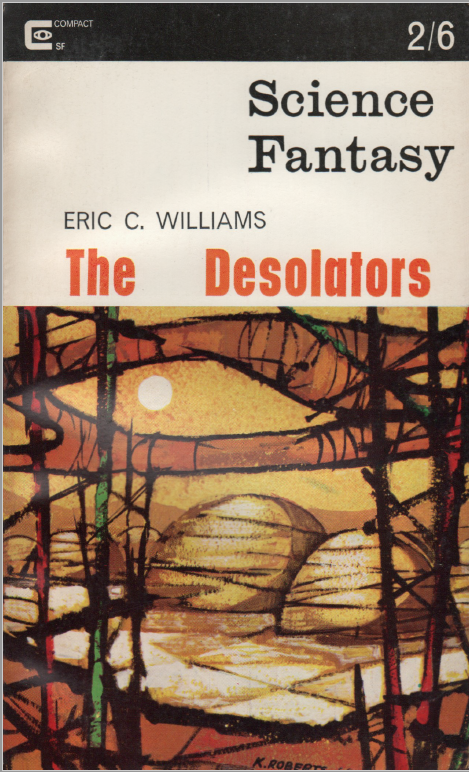

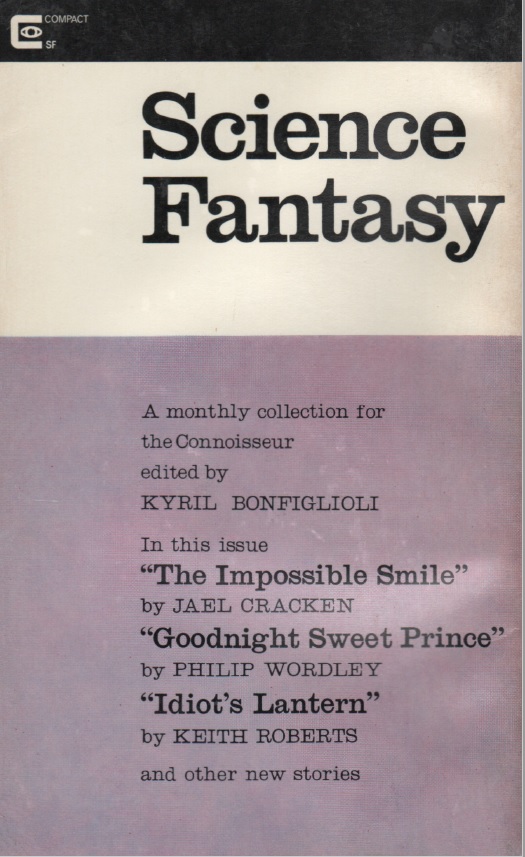

This is a particularly exciting time with the British magazines this month. After the announcement of the end of Science Fantasy in the February issue, we now have Impulse, “The NEW Science Fantasy”, as it says on the cover, and a bigger, bolder, thicker New Worlds – albeit with a shilling rise in the price of each.

Do I get extra value for my extra two shillings a month? I’m looking forward to finding out.

Well, the cover of the new Impulse is interesting. There’s nothing like selling yourself with a roster of names on the cover – and the list is impressive, admittedly. The cover artwork is reasonable too. Gone are the Keith Roberts covers (more about him in a moment) to be replaced with a rather unusual cover by “Judith Ann Lawrence”, though we may also know her as Mrs. James Blish.

As Kyril points out in his as entertaining as ever Editorial, there is even a theme to the issue, that of “Sacrifice”. Sounds intriguing.

To this month’s actual stories.

The Circulation of the Blood, by Brian W. Aldiss

We start this issue with the return of one of the current and most vocal exponents of the New Wave, Brian Aldiss. Clem Burke is an oceanologist who has returned to his tropical idyll to meet his wife and son after spending six months investigating ocean currents. We discover over the course of the story that he and his team have discovered a new virus carried by microscopic copepod that seems to imbue immortality upon the creatures who ingest it.

This is typical Aldiss, in that the story that at first reads as if it is a travelogue of tropical islands. It could almost be published in any magazine. However this is Aldiss, and what the author then does is reveal a science-fictional element gradually, by which time of course the reader is hooked. What we end up with is a world on the edge of major irretrievable evolutionary change from which there is no going back.

Brian would hate me for saying this, as he’s not a fan of the author’s writing, but to me this one felt like it had a touch of the John Wyndham “global catastrophes" about it, although it leaves the reader wondering “What happens next?” at the end. It is about what would be the consequences of what will happen when this secret discovery is revealed to the world, and the effects afterwards, on society, on relationships and on the world’s ecology. A good start. 4 out of 5.

High Treason, by Poul Anderson

From a story that’s rather British in tone to a stridently American tale. Edward Breckenridge is a space pilot currently imprisoned and on trial for treason. The reason is that he was the commander of an attack force given the job in a last ditch effort of wiping out the enemy’s home planet, but who took an alternative decision, sacrificing his own family and career to do so.

I have always thought of Poul as a right-wing writer, and consequently this story is something I didn’t expect. To begin with it reads like a typical sf Space Opera tale from the States, with its roots in Doc Smith’s Lensmen, all about honour and loyalty, but then takes a left turn into the unexpected.

It shows us that when difficult choices have to be made, the answer is far from simple and leaves us with the moral dilemma – would you, faced with a relatively benign enemy, make the same decision?

Whilst the tone of the story is what I would expect in the American magazines, this one is a tale that I don’t think you’d find in Analog. Surprising. 4 out of 5.

You and Me and the Continuum, by J.G. Ballard

And then from a story that appears at first to be traditional to one that is most definitely not. If Aldiss is often seen as “the voice” of New Wave, then here is perhaps the group’s leading exponent, making a welcome return to the British mags.

Ballard has set himself quite a challenge here, as the banner suggests: “The theme of sacrifice led me to think of the Messiah, or more exactly, the second coming and how this might happen in the twentieth century.”

Written in that typically fractured, disjointed manner, the disparate pieces together make up a story which doesn’t quite reach its lofty ideals yet must be admired for its ambition. Deliberately provocative, ambitiously subversive, the story is filled with phrases that remain in the memory after the story has been read. One where the parts may be greater than the sum of the whole. 4 out of 5.

A Hero’s Life, by James Blish

The banner on this one tells me that for the first time this is the first original piece published in Britain from this American author (admittedly living in Britain). I’m sure that you will know him for his Cities in Flight series of stories if nothing else, although I know him more for his literary criticism as much as his fiction writing.

It is a strange story about a poisoner on a Romanesque planet where being a traitor is a valuable trade. As a traitor Simon de Kuyl is given untouchable status, but he is about to have his twelve days of grace expire. The story is about how he manages to use his wits to survive, finding himself playing a complex game with the planet’s leaders. Lyrical, a bit grim, one that seems to combine Samuel Delany’s style of grimy underworld writing and when de Kuyl is tortured produces stream of consciousness gibberish with more than a touch of the lyrical Jack Vance. It’s ambitious, but feels a little like it’s trying too hard. 3 out of 5.

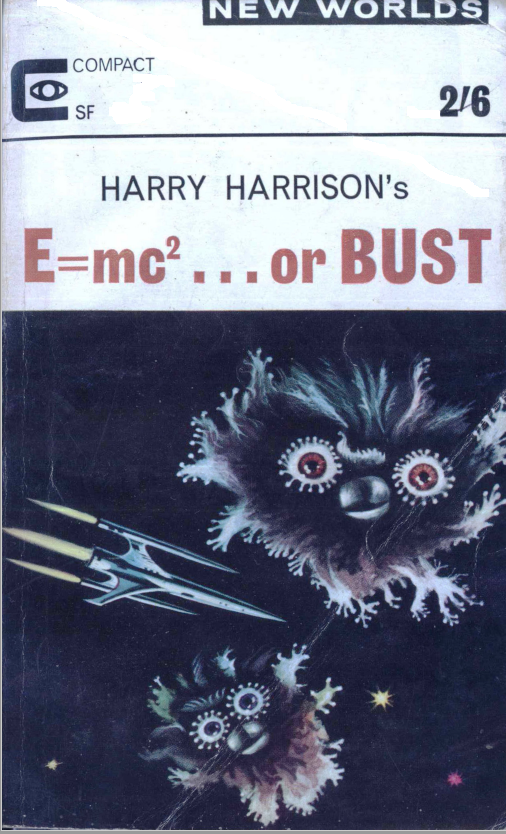

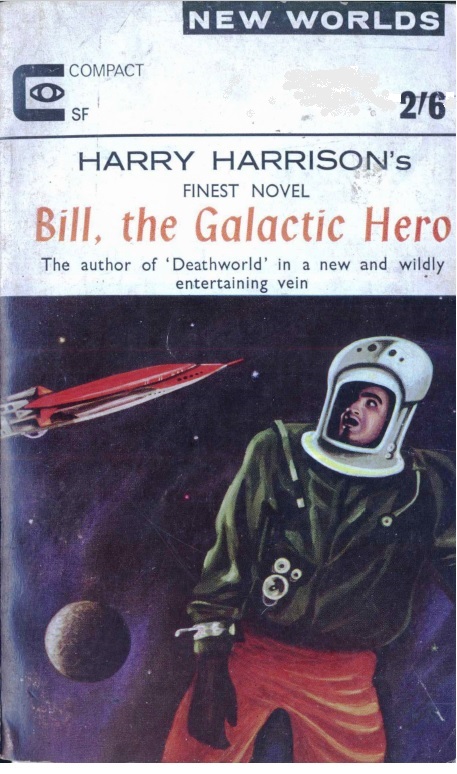

The Gods Themselves Throw Incense, by Harry Harrison

Friend and colleague of Mr. Aldiss, here’s another name that seems to be forever in the British magazines at the moment. This time Harry is into Space Opera mode, but not the farce of Bill, the Galactic Hero (thank goodness!), but instead a darker, more visceral story.

The explosion of the spaceship Yuri Gagarin leads to a motley trio of survivors in an emergency capsule. With oxygen running out and rescue unlikely for at least a few weeks, the story is how they survive – which means that one of them needs to make the ultimate sacrifice in order for the others to live. A story which examines what could really happen when people are put under significant life-changing stress. Like Poul Anderson's story this month, this is not a story of honour or glory, nor is it particularly pleasant, but it is memorable. 3 out of 5.

Deserter, by Richard Wilson

Continuing the theme of sacrifice, Richard’s story tells of William Leslie, a soldier who with an impending war coming, marries Betty. The couple are immediately separated, because – wait for it! – it’s a war of the sexes! Bill deserts to meet Betty, and does so, but is then arrested and sent for a court-marshal. It all seems a little silly. Not the best story in the issue. 2 out of 5.

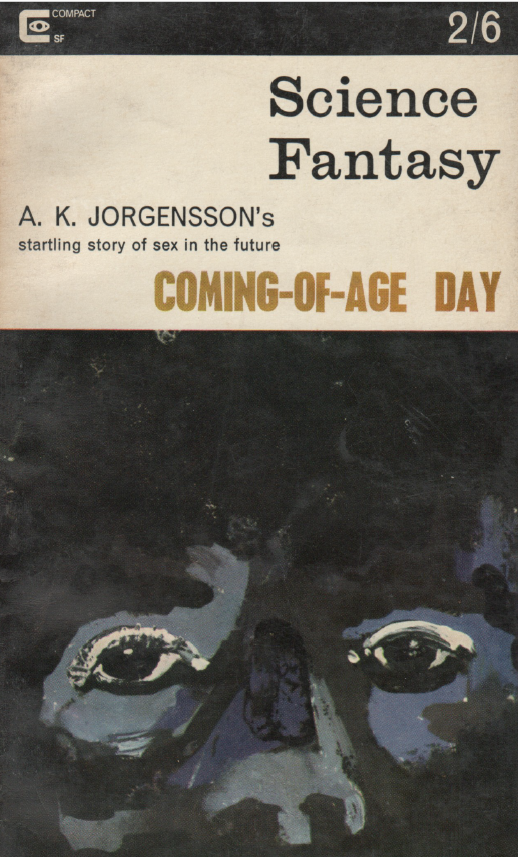

The Secret, by Jack Vance

Having mentioned the lyrical American Hugo-winning author already, here he is, with a coming-of-age story. Rona ta Inga lives in idyllic tropical paradise with food, shelter and all the company he could want. However, one day as the oldest of the group, he, like many of his friends and predecessors before him, feels the urge to sail away to the West, where he discovers "the secret" and his innocent child-like life is changed. It’s a one-trick tale, but well done. Precise wordage mingles with metaphor. 3 out of 5.

Pavane, by Keith Roberts

This is the first of what I believe will be many stories spread over the next few months, and something a little different from Mr. Roberts, who in this same issue we are told has taken on the responsibility of assistant editor.

Pavane is an alternate history where Elizabeth I was assassinated in 1588. As a result, Protestantism has not taken hold in England and Roman Catholicism still dominates the world. With the Roman Catholic view of science being one of suspicion, and innovation supressed, inventions have not as developed as they have been here today. Although it is still the 1960’s, here we have Keith’s descriptions of this strange new-yet-old world which runs a feudal system and where communication is not through telegraph or radio (electricity not invented) but by flags.

The story is focussed upon the duties of Rafe Bigland, a signaller whose job is to pass semaphore flag messages down the line to the next semaphore station in a distinctly more rural England. It shows us Rafe’s job at a semaphore station and through a bit of history how he got to this prestigious position. Think of it like a particularly British Lord Darcy story.

I’m not sure where it is going – presumably we will discover more in later stories set in the same world – but I enjoyed the worldbuilding and the sense of timelessness that pervades this slower pace of life. There is a deliberately shocking ending, which I guess does fit with the overall theme of the issue. 4 out of 5.

Summing up Impulse

Well, this one hits the ground running. What a superior issue! Impulse covers an impressive range of story. From Space Opera to alternative history to New Wave, each story this month combines this impressive variety of styles from a host of well-known authors to create an all-star issue. There’s little I didn’t like about this one. I particularly enjoyed the Aldiss, the Poul Anderson and the Keith Roberts, though if I had to pick a weak story it would probably be Richard Wilson’s Deserter, which was a little overwrought.

We seem to have started well. Can this month’s New Worlds compete?

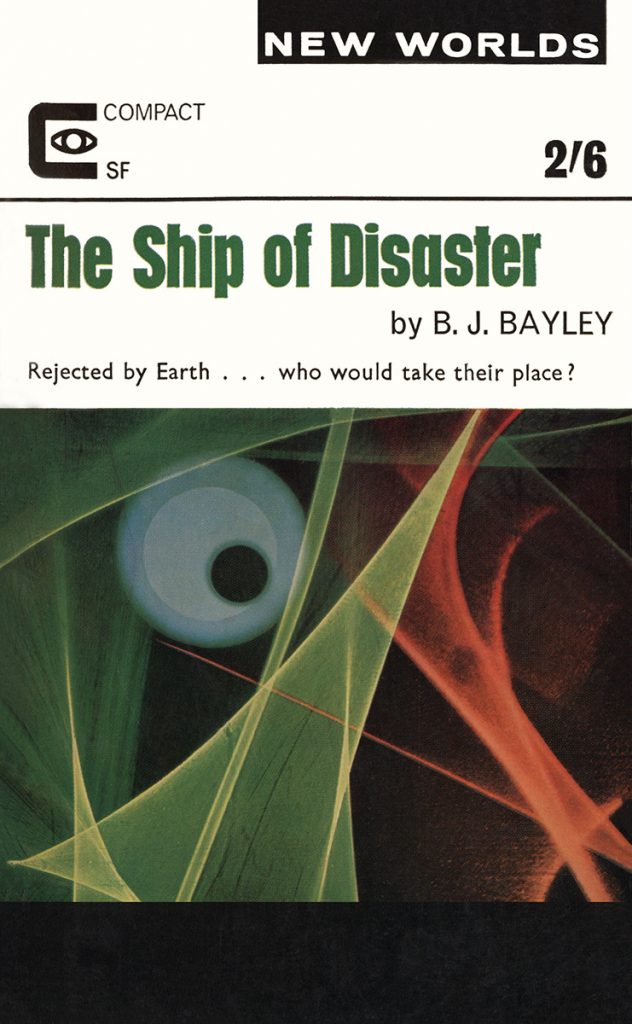

Onto this month’s New Worlds

The Second Issue At Hand

After last month’s rally against the old guard, this month Mike Moorcock is attempting that perennial theme of trying to summarise what Science Fiction means to him and how fans can make it matter. It’s a nice summary for all those jumping on board at this point, but I’ve read similar before.

To the stories!

Illustration by James Cawthorn

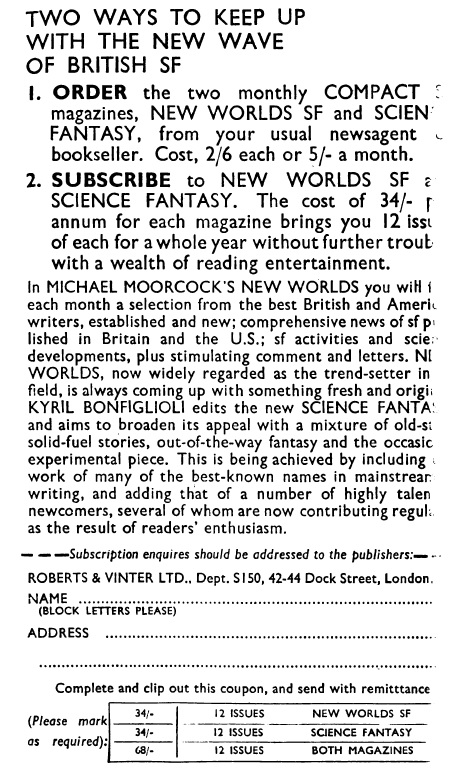

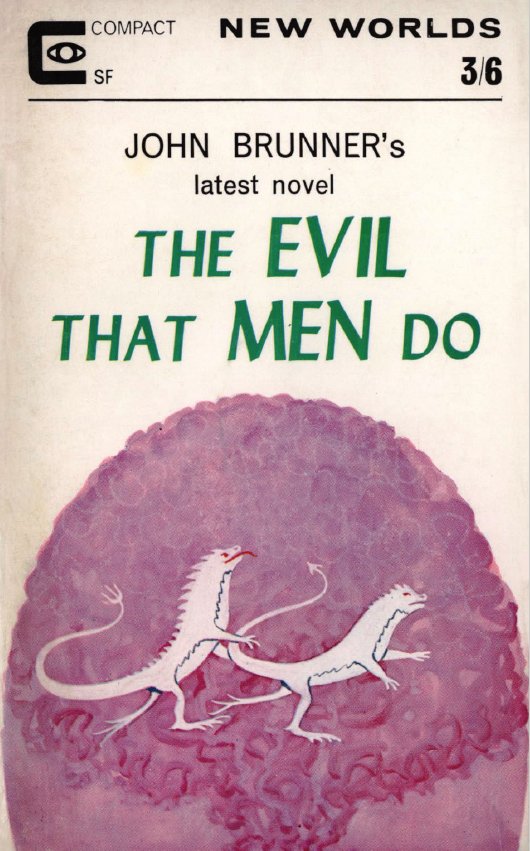

The Evil That Men Do (Part 1), by John Brunner

I think we’ve had a bit of resurgence with John Brunner in the magazines of late. I was under the impression that even with the use of various pseudonyms, the magazines had lost him to the US magazines and writing novels, but in the last few months we’ve had stories (The Warp and the Woof Woof, last month) and non-fiction articles (Them As Can, Does in the January 1966 issue) in these pages, and now a novel split into two parts. This is different though in that it is less science fiction and more of a horror novel.

Godfrey Rayner’s party-piece is that he is a hypnotist, although he really uses the skill as a psychological tool. When persuaded to perform at a party, he does so reluctantly, to find the quiet young girl Fey Cantrip is upset by the process. Whilst not Rayner’s intended participant, Fey goes into a trance and talks of a nightmare involving a white dragon. When Rayner discusses what has happened with his psychiatrist friend Dr. Laszlo, they are surprised to find that Laszlo has a patient in Wickingham Prison who has recounted what sounds like the same dream (and the reason for one of the silliest covers I've seen on New Worlds lately.)

Lots of setting up here, which reads well but then just as the story gets going, it stops. What is the connection between the two dreamers and why are they having identical dreams? We’ll find out next month. This is OK, and reads easily, but as this is something with more of a Fritz Leiber / Weird Tales vibe about it, it’s not typical Brunner, and I would argue not his best. Kudos for trying something different, though. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by Douthwaite

The Great Clock, by Langdon Jones

One of the points that’s surprised me lately in New Worlds is that Langdon Jones manages to pull a double shift. Not only is he the Assistant Editor, but he’s managing to create a line of intriguing fiction as well. They haven’t always worked for me, but I can’t deny that they are usually quite ambitious both in style and content. This one’s another allegorical one, about a naked man who finds himself giving his life’s service to the working of a giant clock. I get the idea that it is probably about the passage of time and the uselessness of spending an entire life giving service to a machine. Some nice descriptions of the workings of this enormous edifice, but in the end it seems rather pointless. It wouldn’t happen inside Big Ben, now, would it? Weirdly, it rather made me think of the film Metropolis. 3 out of 5.

From ONE, by Bill Butler

A poem, from a new name to the magazines. It’s about burning animals and dinosaurs. Marks for effort, but it doesn’t stir me to any kind of emotion. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Psychosmosis, by David I. Masson

And another story from who is probably my favourite ‘new’ author of the moment – this is his third story in three successive months. Again, this story is quite different, this time set in some kind of primitive cultured society.

To begin with, it is about a death in a tribal village, which leads to a naming-feast and much partying. However, in the aftermath Nant, one of the husbands is missing, followed by his newly-renamed wife Mara (once named Nira) in something referred to as a “double-vanishing.” We discover that they have passed over into The Inside, a realm where the village cannot see or hear them.

We then have two worlds – the first, the Faded lands of The Hard of Hearing, which is a harsh and difficult life with a language to match, whilst those who have passed over to The Inside, the Invokers, have a life of relative pleasure and luxury, which is again reflected in the language.

Returning to the land of the Hard of Hearing there is a boar hunt. Tan is regarded as a hero for surviving and killing many animals. However, like Nant and Mara before, when he goes to find his girlfriend Danna it seems that she has gone missing. He searches for her, eventually dies and passes over to the Inside where he meets all of his friends again, including Danna.

As is often the case on a first read of Masson's stories, I’m not quite sure what it all means. All the story really does is depict two opposing societies – is it an allegory for Heaven and Hell, for example? – but it is entertaining enough. as Masson manages to indulge in his love of language to depict the differences in society and lifestyle. The second tribe are, according to the author, ‘saved’, whilst the others are doomed, as shown by the last sentence.

Not sure that this one entirely works for me, but it is still impressive. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by Douthwaite

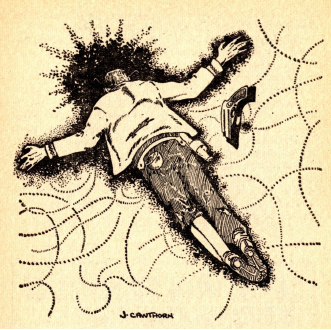

The Post-Mortem People, by Peter Tate

Another new name to the magazines, or at least me. A strange tale of men and women who go around literally rubber-stamping dying people with their time of death in order to allow organ harvesting. The latest in another depressing dystopian setting, this one is typically sombre and actually rather unsettling. 3 out of 5.

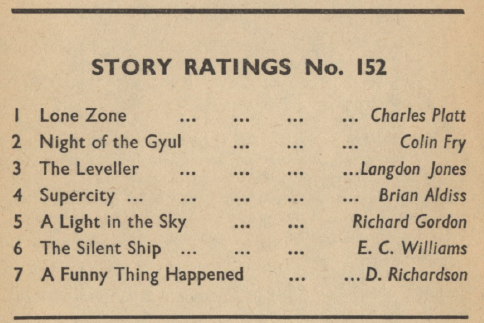

The Disaster Story, by Charles Platt

Charles’s presence in the magazine in recent months has been a constant, with often well-received stories and entertainingly grumpy reviews in New Worlds. The Disaster Story is an attempt by the author to become deliberately more Ballardian, beginning with the statement “This is an attempt to isolate and express the ingredients which endow a distinct type of science fiction with unusual appeal.”

Well, they do say that imitation is the best form of flattery and if so then Ballard should be pleased. There’s nothing like ambition, but whilst The Disaster Story echoes Ballard in its visually dramatic and lyrical imagery and like some of Ballard’s tales is made up of short, discordant paragraphs, it is not as good as Ballard. Compare with Ballard’s story in this month’s Impulse and this is weaker, though a brave attempt. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

For A Breath I Tarry, by Roger Zelazny

I mentioned how much I enjoyed Roger’s writing when I reviewed Love is an Imaginary Number in the January 1966 issue of New Worlds. It seems that Mike Moorcock is similarly impressed, as here’s another story. I think that this one is just as good, if not better. It is a post-apocalyptic tale about Frost, who is a sentient computer created by Solcom, with dominion over half of the Earth. Over ten thousand years, Frost has taken on a hobby – that of studying Man, even though Man has long gone. At the South Pole there is the Beta-Machine, created by Solcom to work in a similar way over the Southern Hemisphere. Solcom now watches over both of them from space.

Opposing Solcom is Divcom and The Alternate, a computer system originally meant as a back-up to Frost and The Beta that through a chance accident to Solcom has also been activated. The two systems have spent the last few thousand years trying to remove the other – Frost claiming that the Alternative should not have been made operative in the first place, Divcom claiming that Solcom has been damaged and needs replacing. Over time this has created a somewhat uneasy but stable peace.

When Mordel, a robot created neither by Solcom or Divcom, strikes up a conversation with Frost, they find that they have a common interest – to study humans. This leads to Frost and Mordel examining a human relic – a book on Human Physiology – and then sharing of ideas on what is the nature of Man. This leads to Frost becoming determined to attain Manhood, and much of the rest of the story is about how far it goes towards that.

This story of god-like machines wanting to comprehend and even become like Man is thoughtful and well written and shows that Roger is writing material that is setting the standard across the Atlantic. I wouldn’t be surprised to see this one nominated for Awards in the next few months. Robots with personalities and a conscience – I wonder what Asimov would make of it? 4 out of 5.

Illustration by Douthwaite

Phase Three, by Michael Moorcock

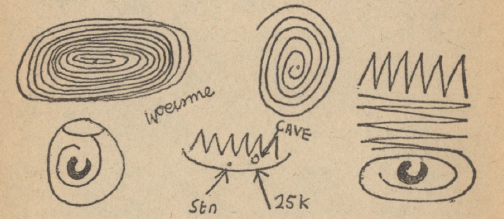

Nice to see the editor as author again. This is the third Jerry Cornelius story (having first been seen in issues 153 and 157). Moorcock mixes cultural references with pagan mythology and strange happenings in time through the actions of his action-hero and his side-kick, Miss Brunner. (Where has Cornelius's wife gone to, I wonder?) This time Jerry goes to Scandinavia to try and find his brother Frank who appears to be “in a bad way” following the events of the previous story. Frank leaves a strange map:

which Jerry and Miss Brunner use to track Frank down, to a place with secret Nazi constructions in some variant of the Hollow Earth theory. In terms of the bigger picture, it all seems to be connected to the super-computer mentioned in the last story.

Wildly imaginative, if supremely improbable, the rattling pace almost covers up the fact that this is an extract of a novel soon-to-be-published. As an extract, it doesn’t make much sense. But then that may be the point. 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews

We start with a big-hit reviewer this month. J.G. Ballard takes up the mantle and reviews The Childermass, Monstre Gai and Malign Fiesta by Wyndham Lewis. Must admit, I always confuse Wyndham Lewis with the already-mentioned-this-month John Wyndham, he of The Day of the Triffids fame, but Ballard makes a good case for reading Wyndham Lewis.

James Colvin, the Editor-by-Another-Name, tackles the paperbacks. He reviews J G Ballard’s story collection The Fourth Dimensional Nightmare in some detail before going onto a very brief mention of Isaac Asimov’s latest British releases.

Keeping that literary viewpoint he then reviews Steppenwolf by Herman Hesse and Jorge Luis Borge’s Fictions which, as expected, is regarded as “sublime”, and then Ray Cummings’s Tama of the Light Country for a bit of contrast. (As an old pulp story it does not fare well.)

Lastly Colvin mentions, but actually does little more than list, a number of Philip K Dick recent publications, stating at the end that they are “much, much better than most sf published recently.”

Like Moorcock, not content with just having a story in this issue, Assistant Editor Langdon Jones, under the heading Rose Among Weeds reviews The Rose by Charles L. Harness. It sells the book well, although as it is published by the same publisher as this magazine, I did cynically wonder whether it masquerades as subtle promotion. Given the reviewer’s usual sense of scorn (so-British!) I hope not.

There are no Letters pages this month.

Summing up New Worlds

In an appropriate moment of serendipity, the back cover subtly points out that this is the 160th issue and the first to have 160 pages. I have been quite positive about the changes in New Worlds in recent months, but the extra space seems to have reenergised the magazine even further. The weaker spots for me are the Brunner and the Platt, but even they are not bad, just eclipsed by the Zelazny and the Masson, both of which are excellent. The range is broad, and perhaps not for everyone, but if I was to point out an issue that epitomises the changes that sf has experienced in the last couple of years this would probably be it. From intangible horror to post-apocalyptic dystopia and decay, from culture bending satire and even a search for meaning, from Ballard-esque imagery to poetry, it is, dare I say it, a diversely classic issue. Moorcock’s editorial summing this up forms the impressive structure upon which current sf can be exhibited.

Summing up overall

Difficult choice this month. Both magazines seem to have benefitted from the extra space more page-age provides. I think that both editors have pulled out all the stops and produced better than average issues – I hope that it lasts. Impulse has hit the ground running, and I liked the the fact that both issues have managed to combine quality writing from both British and American writers to create a varied issue. Overall, I liked more of Impulse than I did New Worlds, but the Zelazny story in New Worlds is perhaps the best I’ve read this month.

So: Impulse has the edge, although – and I say this very rarely – in my opinion both issues are worth reading this month – despite me being two extra shillings down on the deal.

This is a wonderful sign for the future of sf here in Britain. What is also great is that comparing what we get here with what you get in the USA, the difference to me is quite apparent. Absolutely nothing wrong with that – in my mind, a broad genre is a sign of strength, not weakness. We really do seem to be entering some sort of new Golden Age.

To reflect this – next month, more Ballard in New Worlds!

Until the next…

![[July 8, 1966] South Pohl (August 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660708cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1966] Scapegoats, Revolution and Summer <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, July 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Impulse-NW-July-1966-672x372.png)

![[February 22, 1966] A New Age? <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, March 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Impulse-NW-March-1966-672x372.png)

![[November 26, 1965] Plagues and Unicorns <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, December 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Sciene-Fantasy-NW-December-1965-672x372.jpg)

![[October 26, 1965] Mythology and Multiple Earths <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, November 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/nw-sf-November-1965-672x372.jpg)

![[September 26, 1965] Allegory and Mythology <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, October 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/sf-nw-october-1965-672x372.png)

![It’s (Nearly) All About Aldiss [August 22, 1965] <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, September 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Nw-Sciene-Fant-Sept-1965-672x372.png)

Illustration by Douthwaite

Illustration by Douthwaite Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[August 20, 1965] Look both ways (September 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/650820cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 28, 1965] Aldiss, Harrison, and Roberts, Inc. (August 1965 <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650728cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 26th 1965] Mind Control, Aldiss and Time Travel (<i>New Worlds and Science Fantasy, June 1965</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650526coversnew-672x372.jpg)

Appropriately dark art for a dark story. Art by Douthwaite.

Appropriately dark art for a dark story. Art by Douthwaite.