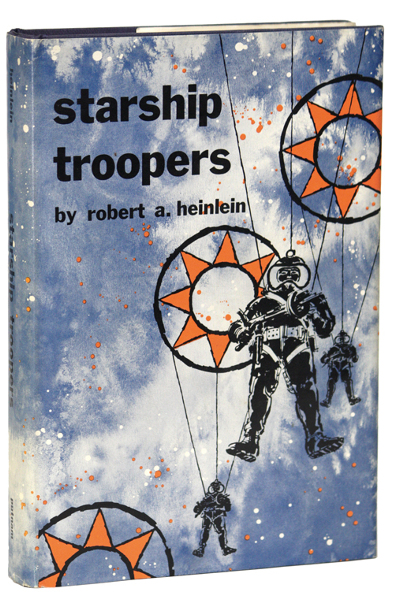

It is common practice for serials published in science fiction digests to get turned into stand-alone novels. Not only does this constitute a nice double-dip for publishers and authors, but it offers the writer a chance to polish her/his work further. Sometimes, the resulting product ends up something of a bloated mess. In the case of Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, the novelization of Starship Soldier (which appeared in F&SF a couple of months ago), the opposite is the case. Heinlein’s expanded story has turned a flawed gem into a masterpiece.

Left virtually intact are the first two acts as presented in F&SF. Johnny Rico is a bright but rather callow youth who joins the "Mobile Infantry" without much forethought. After an intense and vividly portrayed Basic Training, Rico becomes versed in the art of combat from within a suit of powered armor with enough power to destroy a 20th Century tank company. He then goes off to fight an interstellar war against the "Bugs," a hive-mind race of Arachnoids, and their co-belligerents, the humanoid "Skinnies." There is precious little depiction of combat, however, with the exception of a well-executed first chapter (Basic Training is described in flashback).

It was all well done, but the serial just sort of ends without much resolution or pay-off. The novel includes a full third act wherein Rico is involved in a mission to capture one of the Bug "brains" for interrogation/experimentation purposes. This is what the novel needed, and I have to wonder if Heinlein intended it to be there all the time, but was limited by space constraints. It makes the book a must-have, and it is possibly the best thing Heinlein has written to date.

Of course, there is a bit more of the jingoistic, even Fascist pro-militarism speeches issuing from the mouths of various officers and professors. I imagine a number of impressionable young folk will be motivated to enlist after reading the book. I can only hope that we don't fight any major wars over the next decade or two, though so long as the minute hand on the F.A.S. Doomsday Clock remains at two minutes to Midnight, that seems wishful thinking.

Then again, so long as there are just 120 seconds to Armageddon, the next major war is likely to be very short.

Note: If you like this column, consider sharing it by whatever media you frequent most. I love the company, and I imagine your friends share your excellent taste!

P.S. Galactic Journey is now a proud member of a constellation of interesting columns. While you're waiting for me to publish my next article, why not give one of them a read!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.