[This month's Galactoscope features a trio of books by two authors filled with riproar and comic-style adventure. We think you'll enjoy this foray into the past…and future!]

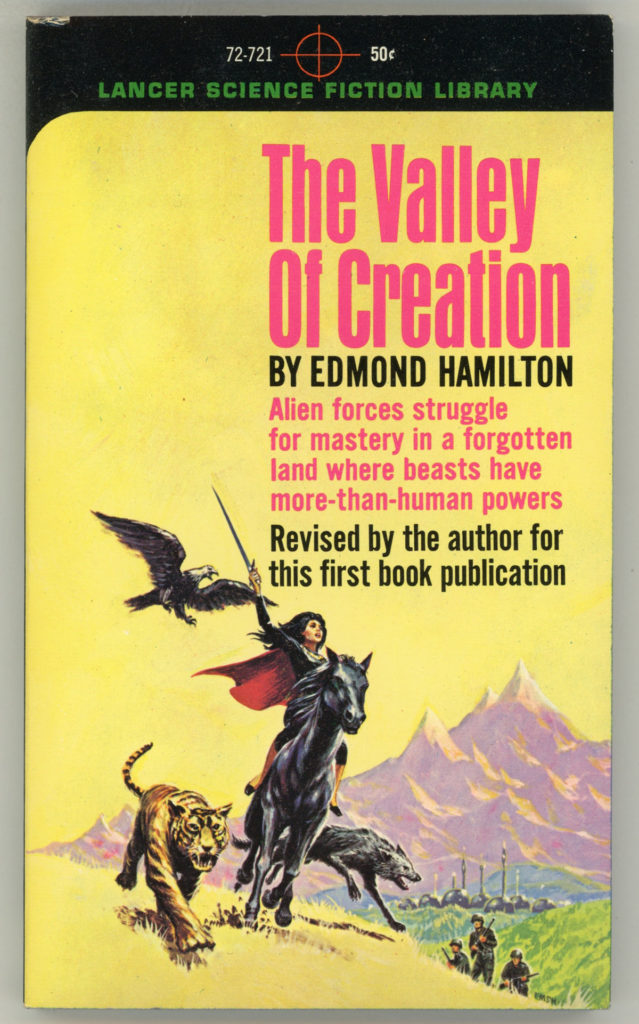

The Valley of Creation, by Edmond Hamilton

by Cora Buhlert

Captain Future was the first science fiction I encountered, therefore I will always have a soft spot for Edmond Hamilton. And so I was happy to find a new Edmond Hamilton novel in the spinner rack of my local import bookshop, even if The Valley of Creation is quite different from Captain Future. The latter is space opera, the former is an earthbound adventure in the style of the "lost world" stories that were popular around the turn of the century.

The Valley of Creation follows the adventures of Eric Nelson, an American soldier of fortune (as he euphemistically calls himself) who got stuck in Asia after the Korean war. Together with a motley multinational crew of mercenaries – a Dutchman, an Englishman, a Chinaman and a fellow American (and a black man, at that) – Eric is fighting in the Chinese civil war, offering his guns and skills to whatever local warlord is willing to pay.

But Eric and his merry band of mercenaries are in a tight spot. Their latest employer is dead, the People's Liberation Army is encroaching and the mercenaries are about to find themselves on the wrong end of a firing squad. Luckily, a man called Shan Kar shows up and hires them to fight his private little war in a hidden valley in the Himalayas, far from the reach of the PLA. A hidden valley where platinum worth millions is just lying around for the taking.

If you're reminded of James Hilton's novel Lost Horizon at this point, you're not alone. Alas, L'Lan, the titular valley, is no peaceful Shangri-La. It is a troubled paradise, where the conflict between Shan Kar's faction, the Humanites, and their enemies, the so-called Brotherhood, is about the escalate.

You'd think that a group calling themselves the Humanites would be the good guys. But you'd be wrong, because the Humanites are bigoted supremacists. The Brotherhood, on the other hand, is committed to equality between humans and non-humans. Non-humans in this case meaning sentient and intelligent animals, who happen to be telepathic as well.

Shan Kar hopes that the mercenaries and their modern weapons will turn the tide in his favour. But their attempt to infiltrate the Brotherhood's stronghold quickly goes wrong. Eric is taken prisoner and finds himself at the mercy of the Brotherhood. As "punishment", he has his consciousness transferred into the body of a wolf via quasi-magic technology.

Forced to literally walk in the paws of his enemy, Eric realises that he is fighting on the wrong side and vows to aid the Brotherhood against his former comrades. And just in time, too, because – quelle surprise – Eric's surviving mercenary pals reveal themselves to be murderous thugs willing to do anything in order to get to the platinum.

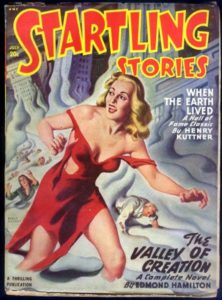

The Valley of Creation is an action-packed science fantasy adventure that feels like a throwback to the pulp era, probably because it is. For The Valley of Creation is an expanded version of a story first published in the July 1948 issue of Startling Stories. This has caused some anachronisms, e.g. at one point Eric remarks that he has been in Asia for ten years, which would set the story in 1960. However, the Chinese Civil War and the annexation of Tibet and the East Turkestan Republic, which are the reason why Eric and his comrades are in the Himalayas in the first place, happened in 1949 and 1950, i.e. shortly after the story was originally published.

The Valley of Creation is an action-packed science fantasy adventure that feels like a throwback to the pulp era, probably because it is. For The Valley of Creation is an expanded version of a story first published in the July 1948 issue of Startling Stories. This has caused some anachronisms, e.g. at one point Eric remarks that he has been in Asia for ten years, which would set the story in 1960. However, the Chinese Civil War and the annexation of Tibet and the East Turkestan Republic, which are the reason why Eric and his comrades are in the Himalayas in the first place, happened in 1949 and 1950, i.e. shortly after the story was originally published.

The chapters that Eric spends in the body of a wolf are the highlight of the novel, for Hamilton makes a serious attempt to describe what the world would look, smell and feel like through the senses of a wolf. The other animals are characters in their own right as well, though the Brotherhood's commitment to equality between man and beast is undermined by the fact that their hereditary leader is human. But then, making the leader anything other than human would have been problematic, considering the plot requires Eric to fall in love with his beautiful daughter.

One can view the novel as a plea for animal rights. Or one can view it as an analogy for racial equality – after all, Eric muses at one point that equality between humans and animals seems as natural in L'Lan as equality between different races is in the outer world. That's an optimistic statement to make even in 1964, let alone in 1948. Furthermore, the Chinese mercenary Li Kin is a wholly sympathetic character, in a genre that is still all too often suffused with yellow peril rhetoric. Another member of the mercenary band is a black man, but unfortunately he is the main villain.

An entertaining novel that's well worth reading, even if it belongs to an earlier era of science fiction. 3.5 stars.

Outside the Universe, by Edmond Hamilton

by Jason Sacks

As the Journey’s resident comic book fan, I try to broaden my understanding of the industry’s creators by checking out some of their text-only work. This month brought two novels by prominent comic book writers. The contrast between the two works is strong.

First up is Outside the Universe by Edmond Hamilton, an Ace reprint of Hamilton’s final Galactic Patrol book. First published in a quartet of 1929 Weird Tales pulps, alongside work by Robert E. Howard, August Derleth, and — I kid you not — Lois Lane — Hamilton’s epic tale of titanic space battles, courageous heroes and intergalactic alliances is a breathless, often overwhelming weird tale.

Written in a long-winded style which reads like Hamilton was desperate to allow the words to tumble from his typewriter lest they find a stray period, Outside the Universe is a wild and wooly journey which involves a million-ship battle between a mighty galactic empire and evil space serpents. Battles are enormous and seemingly endless, and space seems filled with astonishing dangers which imperil every space ship which passes through them. Our heroes and villains fight their ways through bizarre radiation clouds and unexplained hot areas, stars arranged geometrically and people transformed into statues.

It’s a humdinger of a tale, a rousing yarn which throws the reader from cliffhanger to cliffhanger with scarcely a moment to catch their breath — unless they stop to diagram one of the hundreds (thousands?) of 50-word sentences in this book. Hamilton seems to have never internalized the idea of varying sentence length to keep his readers engaged. Perhaps this is an artifact of 1920s pulp writing, but I found I couldn’t keep focus on this book for too long without desperately getting impatient for a quick breather from all Hamilton’s verbosity.

Hamilton moved to comics, where he often wrote for his friend Mort Weisinger on the Superman family of comics. Notably, Hamilton's run on the "Legion of Super-Heroes" tales in Adventure Comics is well known for its breakneck pace — “a new planet every page”, as one critical wag labeled it — and complete paucity of characterization. Apparently Mr. Hamilton changed little as he aged, as this early work reflects those tendencies. Outside the Universe is a hoot but this story has no teeth.

Rating: 2.5

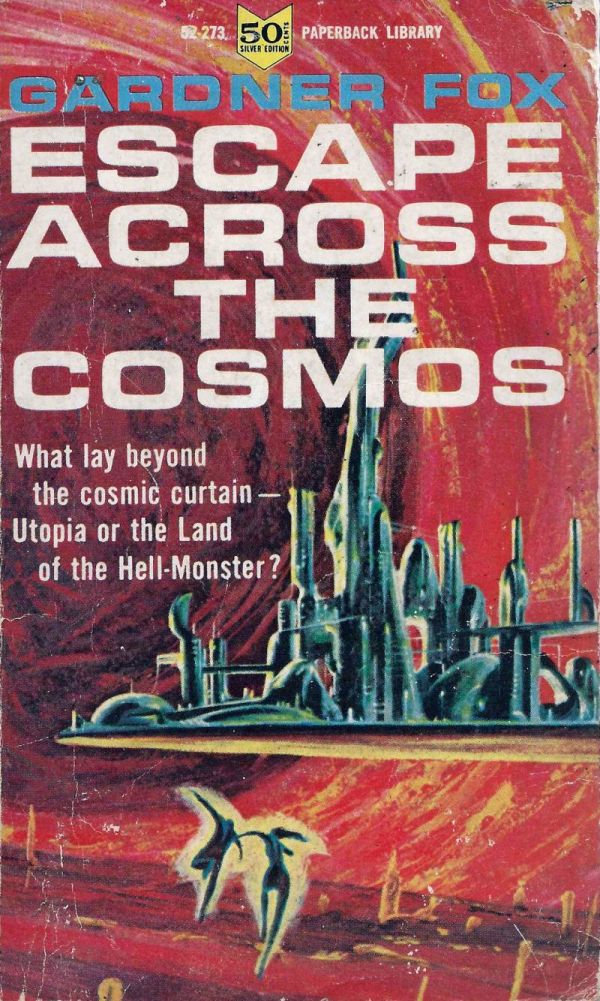

Escape Across the Cosmos, by Gardner Fox

Meanwhile, Gardner Fox has released his newest through the Paperback Library. Escape Across the Cosmos reads at times like a print version of Mr. Fox’s comic book work. In this volume, he delivers a novel about a kind of extradimensional space superhero.

That’s appropriate for the man who has written many classic tales for National Comics’ heroes line, including the memorable “Flash of Two Worlds”, in which the super speedster met his cross-dimensional counterpart. In fact, rumor has it that Fox will be assuming the reins on Batman later this year, taking over the moribund Batman and Detective Comics titles from a team which includes Edmond Hamilton.

Escape Across the Cosmos is the tale of Kael Carrack, a war-ravaged man whose body has been rebuilt to be nearly indestructible. His silicon skin, cybernetic strength and superhuman abilities are urgently needed to defeat the dreaded Ylth’yl, a Lovecraftian monster from another dimension who has killed nearly everybody of importance in his dimension and who hungers to transport his evil to our dimension. In fact, as the story unfolds, it seems Kael has a special connection to the evil creature, one which may save — or doom — our dimension.

In contrast with the Hamilton novel, Fox doesn’t squander characterization for adventure. He takes pains to show readers Kael’s confusion and allows us to become willing and excited participants in the hero’s journey to self-realization. As he and we do so, Kael finds true romance with a human woman, grows into a more perfected version of himself. It will betray any surprises to say that Kael begins to fulfill his destiny by the end of this short book.

This short novel is a clever, quick read. It shines in comparison with Hamilton’s overcrowded prose, as Fox takes pains to allow the reader to move ahead at his own pace. I would have loved to see more depth on the hero and his universe, but perhaps we’ll learn more about him at some point in the future when Fox delivers a sequel in one form or another.

Escape Across the Cosmos reads like an origin story for a new superhero, and for all I know Kael may appear in the pages of National’s Showcase try-out book in the next several months. Maybe Kael will be their next great sci-fi hero. I would certainly welcome him in my comics stack each month.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[June 18, 1964] Bad Comic Book Style and Good Comic Book Style (Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/158064-672x372.jpg)

![[May 26, 1964] Stag Party (Silverberg's <i>Regan's Planet</i> and <i>Time of the Great Freeze</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640526books-672x372.jpg)

![[May 24, 1964] The Darkest of Nights… ( <i>June 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640528Darkest-book-club-1964-423x372.jpg)

![[May 16, 1964] A Mirror to Progress (Chester Anderson and Michael Kurland's <i>Ten Years to Doomsday</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640516cover-595x372.jpg)

![[May 6, 1964] The Predicament: <i>Transit</i> by Edmund Cooper](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640506transitamazon-375x372.jpg)

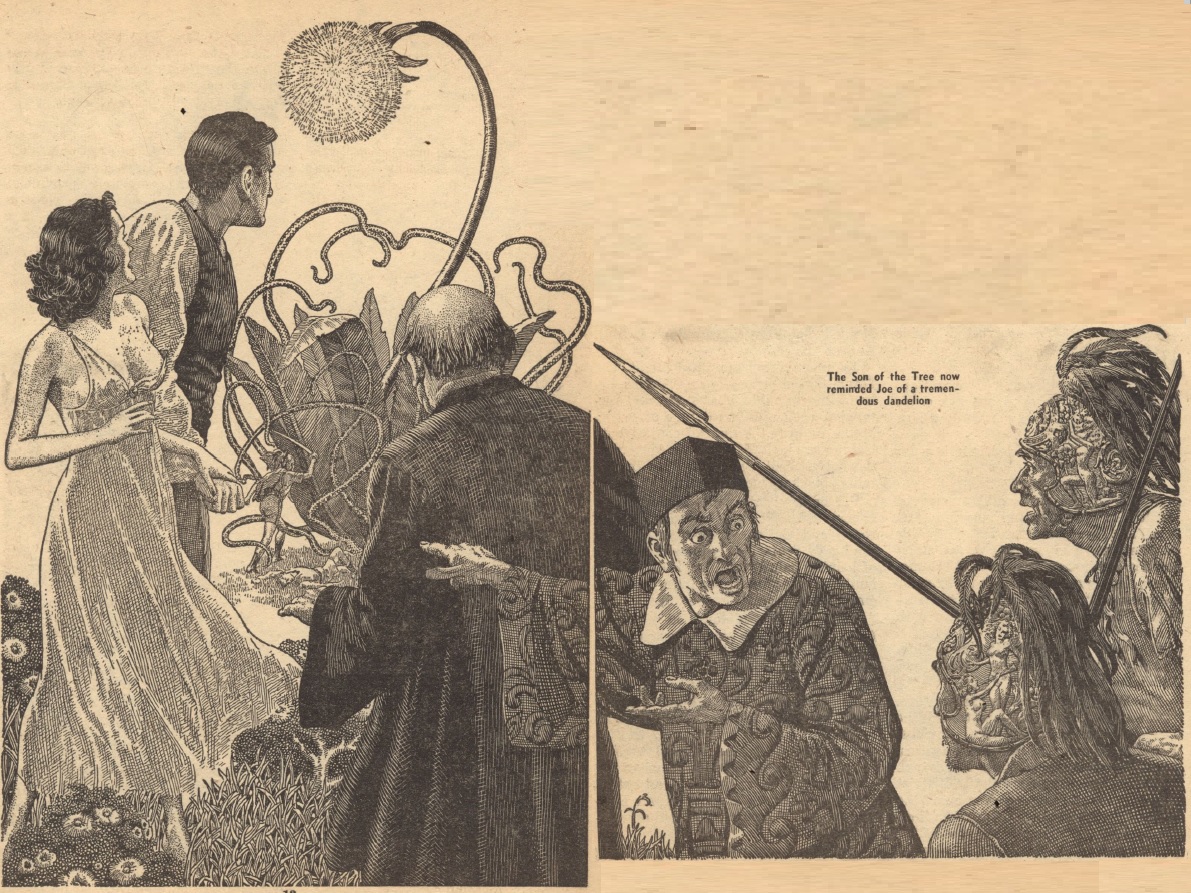

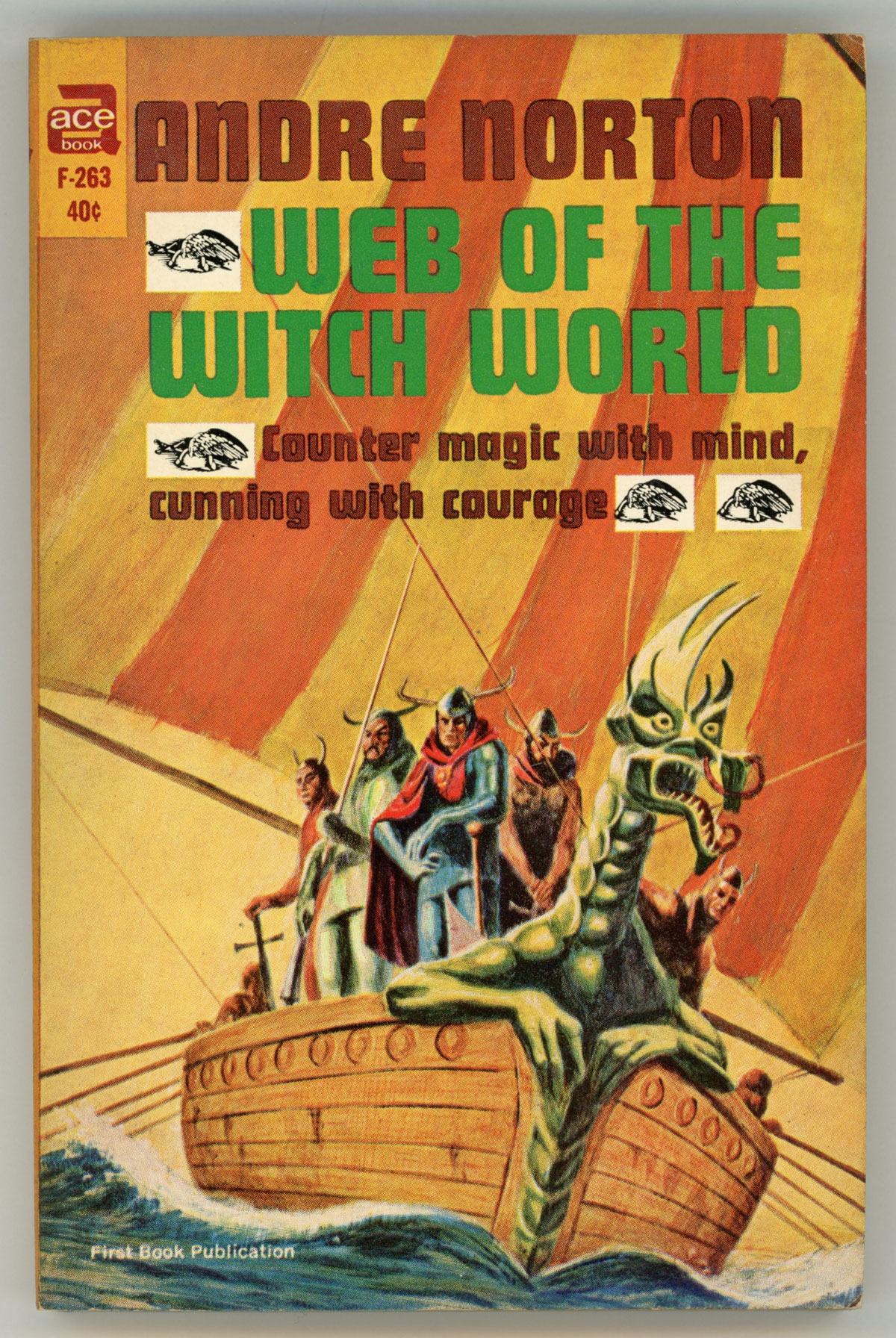

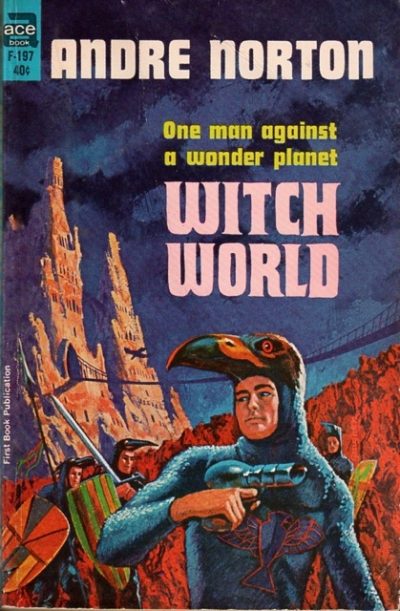

![[April 16, 1964] Of Houses and World Building (Jack Vance's The Houses of Iszm/ Son of the Tree and Andre Norton's Web of the Witch World)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640416double-640x372.jpg)

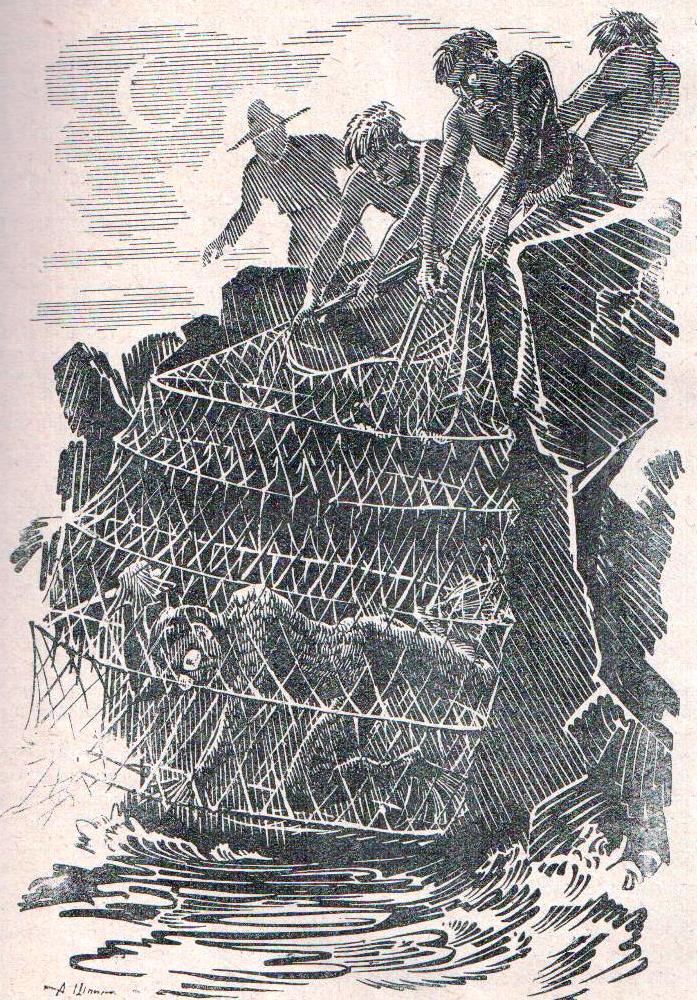

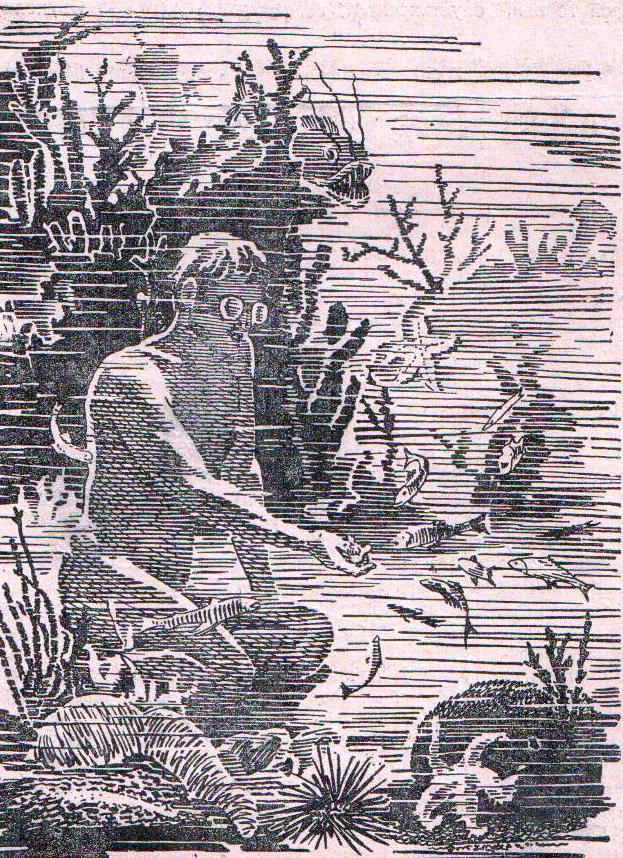

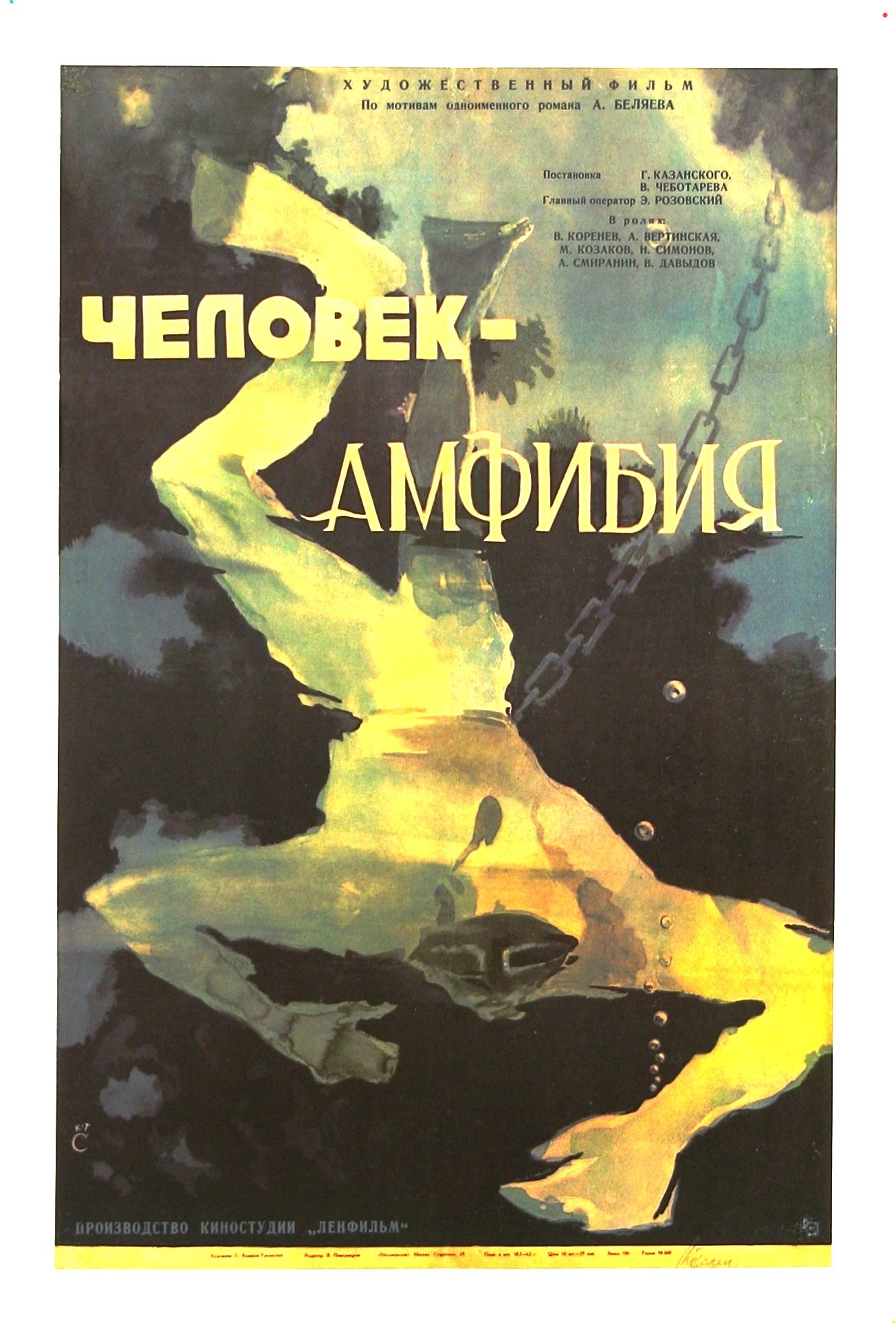

![[Apr. 4, 1964] A taste of brine (the book and movie, <i>The Amphibian</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640403AM_1-672x372.jpg)

![[March 29, 1964] Five by Five (March Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640329marooned-1-417x372.jpg)

![[January 26, 1964] Sophomoric (Laurence M. Janifer's <i>The Wonder War</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640126cover-465x372.jpg)

![[January 10, 1964] Journey to the Stars, Journey into the Self (<i>Starswarm</i>, by Brian Aldiss)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640110cover-672x372.jpg)