by Gideon Marcus

A week is a long time in politics

The British Prime Minister Harold Wilson is fond of noting that a lot can change in just seven days. In American politics, the last seven days have witnessed a lifetime of tumult.

It was just last year that President Johnson was polling in the 70s. When Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy, stand-offish, brainy, tepid in his commitment, took to the field last November, few took his insurgent, Anti-Vietnam-War campaign seriously. Least of all, President Johnson, who did not even apply to be on the ballot in New Hampshire's primary, scheduled for March 12.

Then the Tet Offensive happened, giving lie to the idea of slow but steady progress in Southeast Asia. The Credibility Gap between the populace and the President became a canyon, and when the dust had settled, Senator McCarthy had garnered just 230 votes less than LBJ in the year's first Democratic primary.

Just a few days latter, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who had last year demurred from running, referring anti-war supplicants in McCarthy's direction, decided to throw his hat in the ring. The Democratic insurgency has become a full-on party civil war.

Johnson's complacence reminds me of Georges Ernest Boulanger, who in January 1889 was elected deputy for Paris and seemed on the verge of leading a personal coup against the Third Republic. But on the fateful day of January 27, when the crowds roamed the streets and chanted his name, the would-be despot was nowhere to be found. Turned out he had missed his moment, lost in the arms of his mistress rather than under arms with his supporters.

Who knows where all this is headed? It just goes to show that even the most promising candidate can fail for lack of sufficient focus on the goal. And this leads me into discussion of this month's issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

by Bert Tanner

Burned batch

Have you ever been careless in the kitchen, not so much as to ruin dinner, but to render it far less palatable than it could have been? All of the stories this month are missing something. Their imperfection lies in missing some quality, or in some cases, an overcooking of sorts. The result is a handful of ideas that could have been good in others' hands, or perhaps with more expert editing, or more time and care in production.

Flight of Fancy, by Daniel F. Galouye

After a long hiatus, the author of the brilliant Dark Universe returns to the pages of science fiction with this, probably the best piece of the issue.

Frank Proctor is an ad man, miserable in his career and his life, shackled to a beautiful woman who insists on tormenting him with affair after affair. But he stubbornly refuses to divorce her, knowing it means financial ruin. His only solace is his recurrent dreams in which he has the ability to fly. He knows it is a stress reaction, but at least it is a moment's surcease.

A greater balm arises: at a company beach party, Frank falls asleep by the shore and immediately begins to soar in his dream. While apparently still in slumber, he meets a lovely young lady, who also possesses the ability to fly. Happily, she is still there when he wakes, and he assumes he must have been sleeping with his eyes open for her to infiltrate his sleep.

Of course, romance is inevitable. But what of his Frank's scheming wife, and will the pictures she took of him and his new love put him over a barrel? The ending is ultimately a happy one, if a bit pat.

This is a well-crafted and vivid story. My only real issue is it feels a bit like wish-fulfillment, and I have to wonder if Galouye just went through a messy divorce.

Four stars.

Dead to Rights, by R. C. FitzPatrick

Crime boss Angelo Amadeo is rubbed out by his second. When the instrument of Angelo's death turns stoolie, the second's devotees enlist a surgeon to recall Angelo to life, reasoning that if Angelo is not dead anymore, then he never could have been murdered.

The problem is, Angelo's body is brought back to life, but the soul inside is most definitely not his. Instead, the reborn inhabitant preaches love of fellow man and everlasting life in the adoration of God.

You can see where this is going.

Too much effort is made to make this a "funny" piece, and the conclusion is obvious from the start. Two stars.

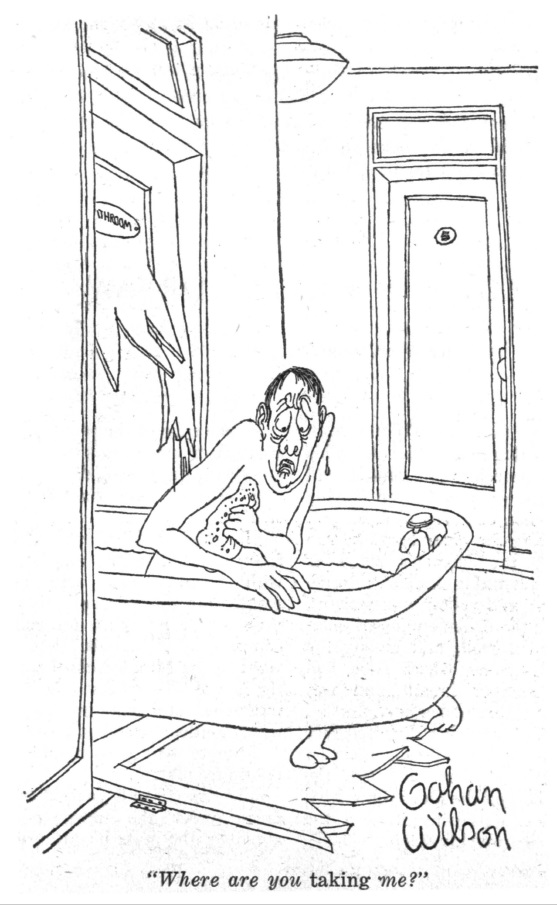

by Gahan Wilson

Without a Doubt Dream, by Bruce McAllister

Antonio and his lovely wife, Alba, wake up one day to find their pine-ensconced villa suddenly surrounded by endless desert. Worse, the insinuating sands are slowly creeping in, destroying all that they touch. Antonio reasons that only his psychic ability is shielding them, but his doubt in the same talent is causing him to lose the battle.

McAllister describes this all in an earnest, somber tone, and he successfully captures the feeling of a pair of foreign protagonists. However, the piece ends rather abruptly, and without a great deal of evolution of the story. Moreover, the tone is a bit too one-dimensional.

Thus, for this third piece by this promising, 19-year old author, I give three stars.

Demon, by Larry Brody

Pinchok, a simple blue-collar worker who happens to be the denizen of another plane, is summoned to Earth in a pentagram by a would-be three-wisher. When Pinchok turns out to be rather useless as a genie, the summoner decides maybe Pinchok should devote his talents to crime…for the benefit of the human, of course.

The concept of demons just being aliens in another dimension, and the art of demonology more a kind of kidnapping (with the implication that it might work the other direction, too, with humans becoming the demons) is an intriguing premise.

This tale, while pleasant enough, just doesn't do enough with it, however. Three stars.

The Superior Sex, by Miriam Allen deFord

William, an astronaut, finds himself the newest member of an all-male harem, subject to an imperious and beautiful mistress. He cannot recall how he got there, but he can recall being from a world dedicated to the principle (if not the assiduous practice) of equality between the sexes. Thus, he rankles at his new role, and in an interview with his mistress, exclaims that he would rather die than live subjugated.

Of course, the truth of his situation is more complex than it first seems.

This is almost a great story. DeFord, an ardent women's libber before the phrase was coined, has a promising message in this piece that is then muddled by its ending. Too bad.

Three stars.

The Time of His Life, by Larry Eisenberg

One of science fiction's few writer/scientists offers up this tale of a middle-aged scientist resentful of forever being in the shadow of his Nobel-winning father, who covets his son's wastrel youth. Said elder has now invented a kind of time travel, but it ages or youthens the traveler rather than sending him elsewhen. In the end, both father and son get what they want.

A decent Twilight Zone-esque piece. Three stars.

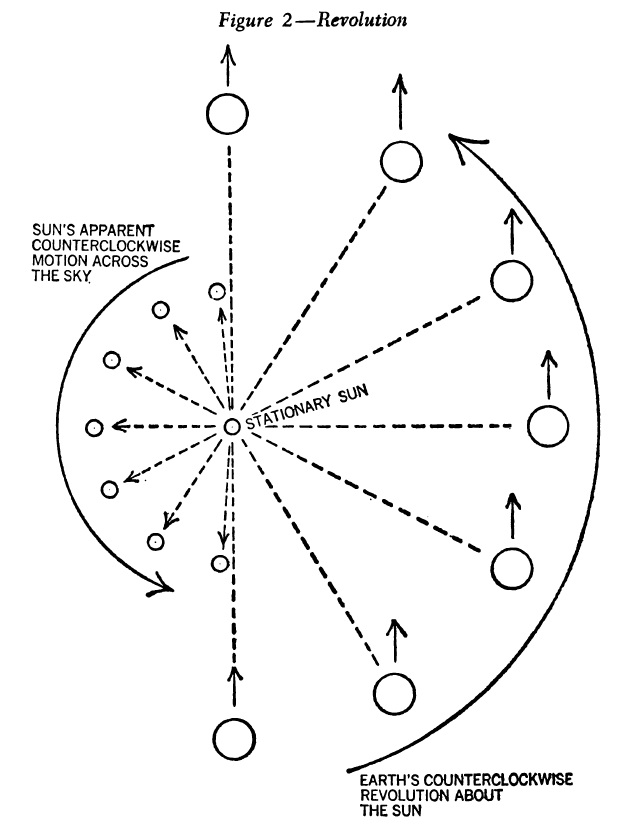

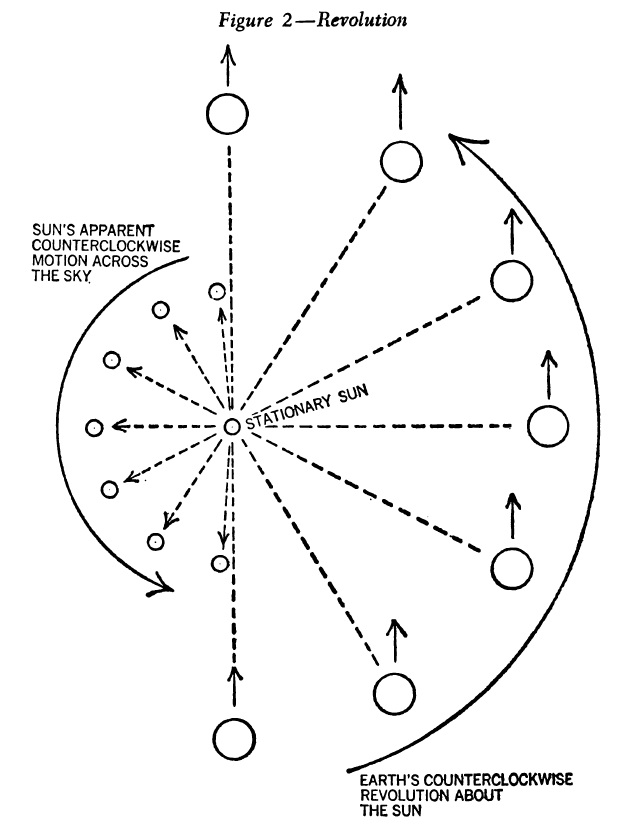

The Dance of the Sun, by Isaac Asimov

This month, the good Doctor discusses the phases of the inner planets with respect to the Earth. He also notes that Dr. Richardson had done a similar piece for Analog a few months back. Frankly, I was more impressed with Richardson's; I found Asimov's dry and difficult to follow. And astronomy was my major!

Two stars.

Muscadine, by Ron Goulart

Mr. Muscadine is an android programmed to produce great books. The secret to his success is the idiosyncrasies fundamentally coded into his electronic brain. But as his eccentricities spin out of control, his agent finds himself conspiring with the android's programmer toward a drastic solution.

Goulart can write well, and he can also write funny. He does neither here. Two stars.

Final War, by K. M. O'Donnell

Finally, an anti-war piece in the vein of Heller's Catch 22. It features a Private Hastings, a war-addled First Sergeant, and an indecisive Captain, whose unit spends three days a week capturing a forest, three days a week being driven from the forest, and Mondays resting. What follows is the usual silliness of war, including friendly fire, endless red tape, and general insanity.

Harrison did it MUCH better in his Starsloggers. This one meanders for way too long in a singular vein. Two stars.

Expected results

With a limp offering like this, it's no surprise that this issue ends up on the wrong side of three stars. It's a shame. Joe/Ed Ferman's mag is often one of the frontrunners in the field. But with a month like this, I suspect Mercury Publishing is going to have an upset when compared against its competitors for April 1968.

Luckily, science fiction is an endless primary, and a month is a very very long time.

</small

</small

![[July 20, 1970] The Goat without Horns…among other things (August 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700720fsfcover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1970] Matters of conscience (August 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Venture-1970-08-Cover-486x372.jpg)

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.![[April 14, 1970] Take this spaceship to Alpha Centauri (May 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Venture-1970-05-Cover-475x372.jpg)

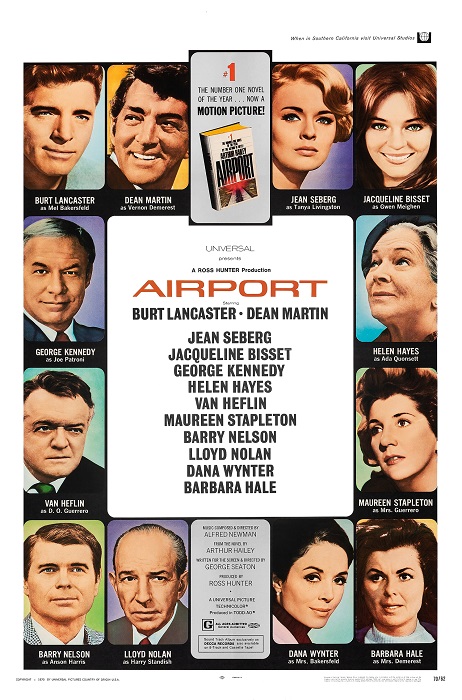

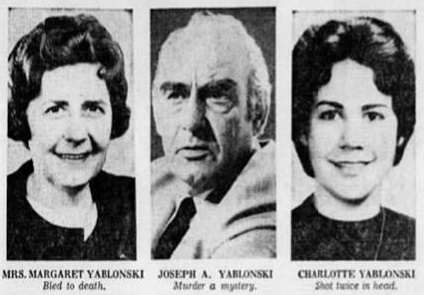

You probably know who most of these people are.

You probably know who most of these people are. I’m still not sold on Tanner’s covers, but this one is better than most. Art by Bert Tanner

I’m still not sold on Tanner’s covers, but this one is better than most. Art by Bert Tanner![[January 14, 1970] Root Rot (February 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Venture-1970-02-Cover-483x372.jpg)

A not very representational image for Laumer’s new story. Art by Bert Tanner

A not very representational image for Laumer’s new story. Art by Bert Tanner![[October 20, 1969] There was a ship (November 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Venture-1969-11-Cover-480x372.jpg)

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage.

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage. Art by Tanner

Art by Tanner![[July 2, 1969] Merging streams (August 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Venture-1969-08-Cover-543x372.jpg)

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner![[April 12, 1969] A New Venture (May 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Venture-1969-05-Cover-494x372.jpg)

The first and last covers for the first run of Venture. Art in both by Ed Emshwiller

The first and last covers for the first run of Venture. Art in both by Ed Emshwiller This singularly unattractive cover is by Bert Tanner.

This singularly unattractive cover is by Bert Tanner.![[March 20, 1969] Going through the motions… (April 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/690320cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 20, 1968] Missed opportunities (April 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680320cover-666x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1967] Field trips (June 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670520cover-449x372.jpg)