by Gideon Marcus

Hail the Sun God

Summer has officially begun.

On June 21, 1965, the northern hemisphere of Earth enjoyed its longest period of daylight (while in Australia, poor fellow traveler, Kaye Dee suffered through the longest night). The Summer Solstice is an event that once had great religious significance, but as the Mosaic religions spread across the globe, celebration of the day waned.

Today, with the rise of neo-druidism (the North American version of it having been related in articles by Erica Frank), the Solstice has once again become a holy day. And 1965's was particularly special: as the Fraternal Order of Druids gathered around Stonehenge, they were treated to the first uncloudy sunrise in 13 years.

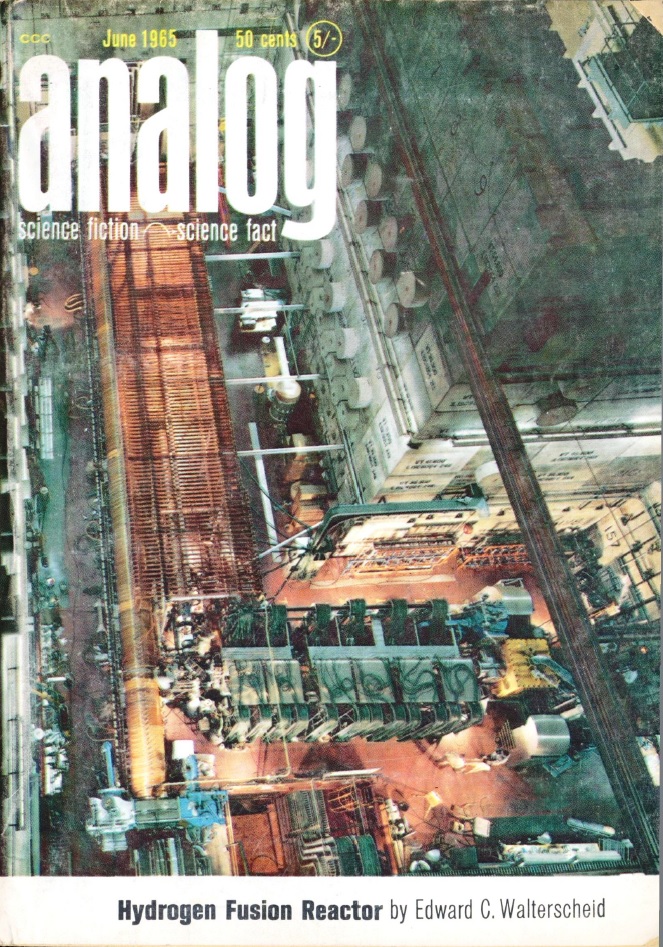

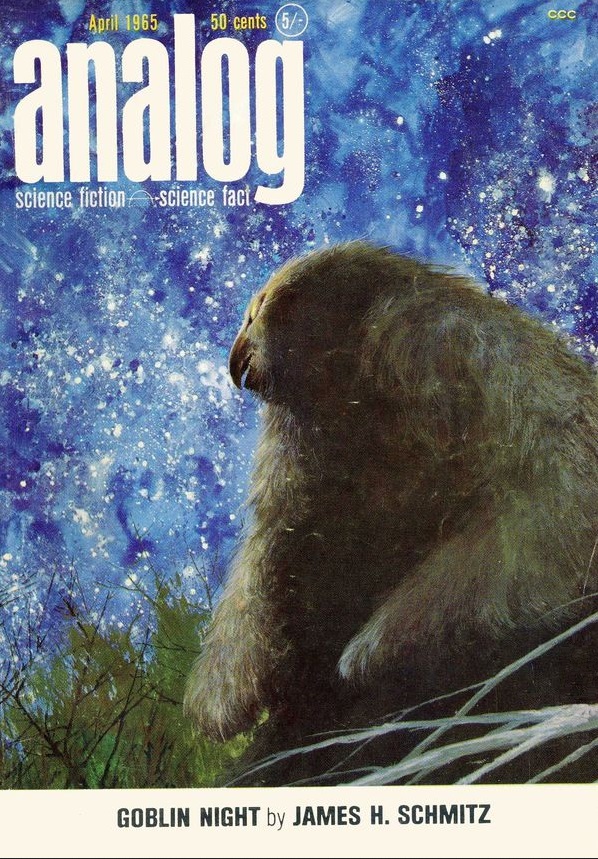

With such an auspicious sign, one might expect that June (July cover date) would be a good one for science fiction magazines. Instead, what we got was a dreary muchness that was more akin to the overcast skies of prior Solstices. And no magazine more exemplifies this drabness than this month's Analog:

Noonday Overcast

by John Schoenherr

Trader Team (Part 1 of 2), by Poul Anderson

by John Schoenherr

Poul Anderson is the Cepheid variable of the science fiction genre: he pulses from brilliance to dullness with regularity. In the midpoints, he produces competent but longwinded stuff like the Van Rijn tales, which detail the exploits of a canny Terran trader trying to enhance his fortune in the Galactic "Polesotechnic League."

Trader Team features David Falkayn, a young cadet we last saw in the mediocre Three-Cornerned Wheel. Thanks to the ingenuity he displayed in that story, Falkayn has been tapped to be Van Rijn's apprentice, his first mission to open up trade on the backward planet of Ikrananka.

The story starts crackingly, introducing the four members of the crew of the Muddlin' Through: Falkayn, the young Captain; Chee, a furry, imprecation-throwing female from planet Cynthia; Adzel, the gentle saurian neo-Buddhist from Woden; and "Muddlehead", the ship's computer. The ship has been in virtual quarantine for several weeks as no representative of the planet's local feudal state will approach them.

Then, in the midst of an intense poker game, Falkayn espies a beautiful woman soldier fleeing from a troop of Ikranankan cavalry. He saves her and brings her aboard ship only to discover that he has given aid to a fugitive of the very polity he is trying to establish relations with!

So far so good, but the next thirty pages are a drag. There's some nice scientific worldbuilding, in which we learn Ikrananka is a one-face planet, that Stepha (the saved soldier) is one of the third generation of spacewrecked humans who now, as a race, hire themselves out as mercenaries, and that Ikrananka would make a nice planet for trade if only its disparate fiefdoms could be unified.

But the story itself meanders in that wordy, shaggy dog style that Poul defaults to when he's on autopilot. The scene in which Adzel gets roaringly drunk and then implicated in a human insurrection is played for laughs, but it's just tedious. When Chee is captured, too, the reaction it elicits is a yawn rather than concern.

And if I have to read another line about what Falkayn thinks of Stepha's physical form, I'll throw the book against the wall. It'd also be nice to see more non-romantic female characters in general (though I will concede that Chee being female is a step in the right direction).

A low three stars.

In the Light of Further Data, by Christopher Anvil

by Kelly Freas

Data is an Anvil story in a Campbell-edited mag, so caveat emptor.

And your caution is justified. Data is a story in newspaper article excerpts of two intersecting threads. The first is the development of a miracle tissue regrowth process that quickly recruits millions of patients seeking replacements for lost teeth. The second is the battle between a professor who asserts that science is the foundation of truth, and the religious community who pushes back on the assertion.

In the end, said professor cheerfully gets a new mouth of choppers, just as it's determined that there is a fatal flaw in the regrowth technique. The punchline is he quits science and becomes a missionary.

The moral, I assume, is that those eggheads don't know everything. It's certainly a philosophy Campbell has flogged to death.

Anyway, it's a dumb story. Two stars.

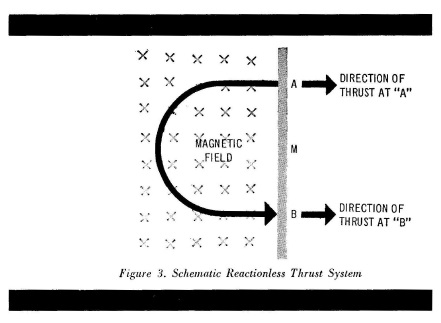

Hands Full of Space, by Stephen A. Kallis, Jr.

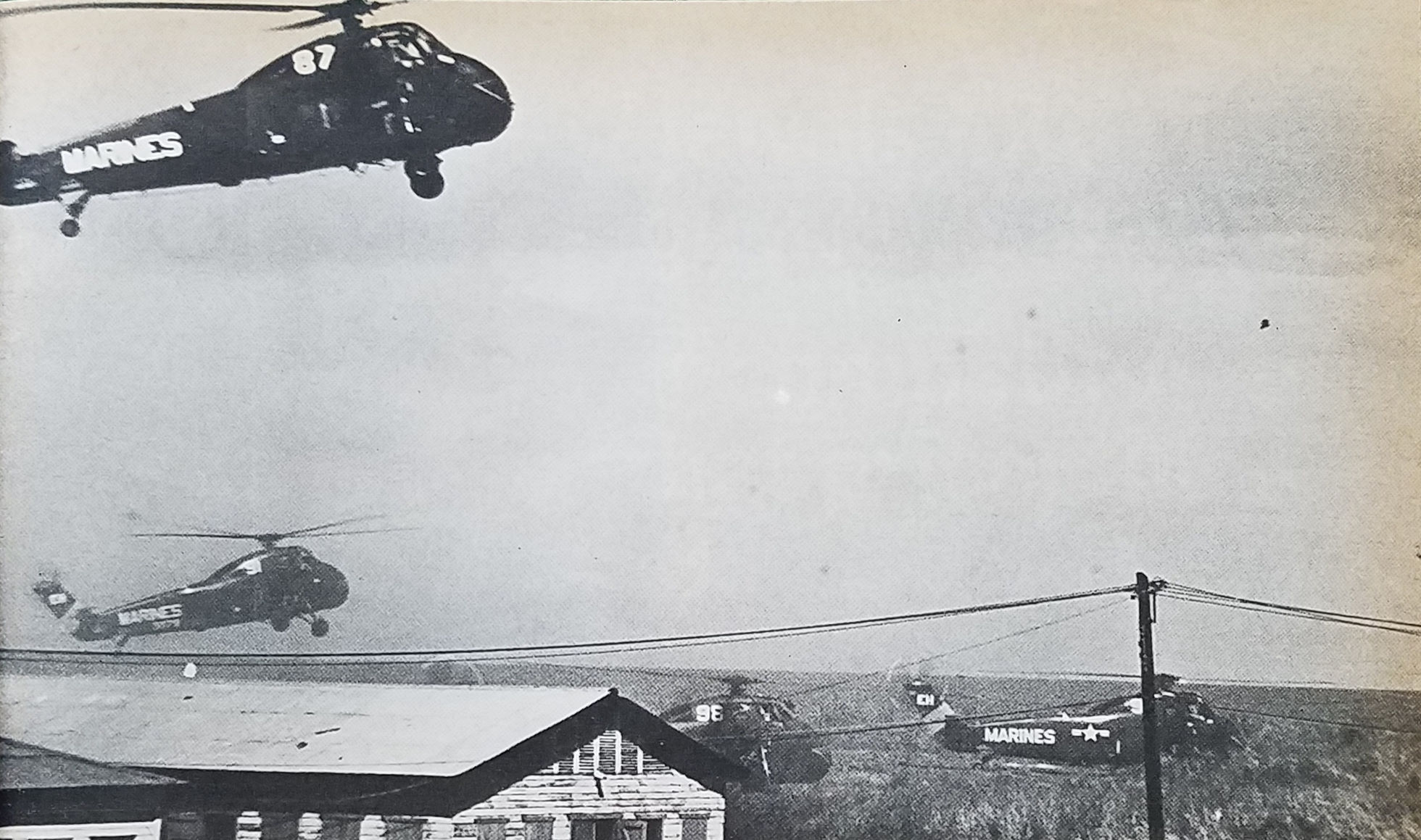

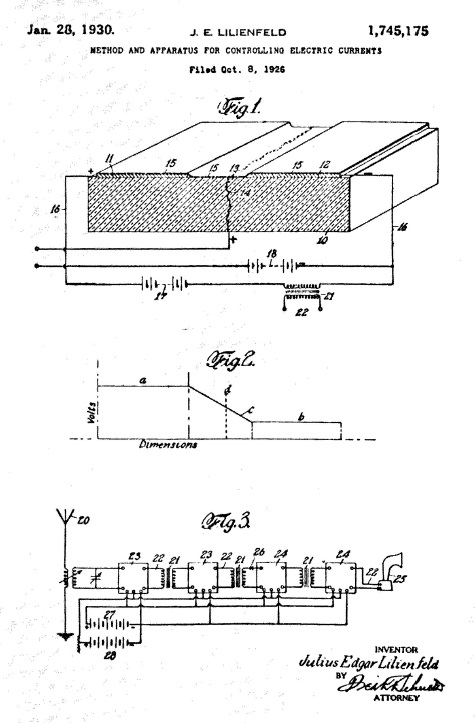

We get a respite of sorts in the nonfiction article. It's about the difficulties of engineering for the intense harshness of space. Kallis tells us what happens to electronic components when exposed to zero pressure — they weld to each other, their surfaces vaporize and then coat other surfaces — and then there's the wear of hellish radiation and the danger from whizzing micrometeoroids.

It's all very informative and accessible, if a bit long and occasionally disjointed. When Analog's science piece is better than Ley's in Galaxy and Asimov's in F&SF, you know the world is truly inconstant!

Four stars.

Soupstone, by Gordon R. Dickson

by John Schoenherr

Here's another ingenue spaceman saves the day story. Soupstone is the sequel to Sleight of Wit, in which a clever human defeats an alien adversary largely by virtue of said alien being implausibly dim.

This time, Major Hank Shallo is sent to Crown World as a special trouble-shooter. The problem he must solve involves a crop of alien oversized grapes that would produce a most exquisite brandy in tremendous quantities if only they could keep them from rotting in the warehouses. It's all a matter of timing in the picking process, you see.

Shallo, an inept buffoon, is unable to solve the problem himself, but he is able to gather all the folks together who can solve the problem, and in doing so, sets them on their way to effecting the solution. And if you know the fable about making soup from a stone (I did) then you get the reference. And if you don't, don't worry — Dickson explains it for you.

Dickson is capable of much better than these "funny" stories, and once again, the ladies are included just for leering.

Two stars.

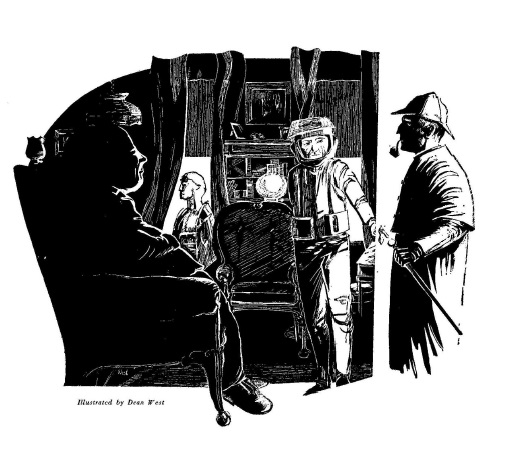

The Adventure of the Extraterrestrial, by Mack Reynolds

by John Schoenherr

It is rare that the science fiction and mystery genres overlap. Asimov's R. Daneel Olivaw tales and Garrett's Lord Darcy series pretty much round out the list. In Adventure, Reynolds crosses SF with The Detective, the one and only supersleuth of Baker Street (though neither Holmes nor Watson are ever mentioned by name).

An octogenarian Holmes is engaged by the spendthrift son of a rich gentleman. The son is putatively concerned for his father's mental health as he has engaged in a Fortean obsession with aliens, which have taken up residence in London, he maintains.

Reynolds is a good writer, and he executes a fair homage to the Doyle style. But while I enjoyed the story, I found Watson's constant and repetitive harping on Holmes to be offputting. And there are only so many times I need to be reminded of Holmes' age through note of his "senility," "chortling," "blathering," "dribbling," "inanity," etc. etc. Virtually every line includes a reference, and it's overmuch.

Also, and this is a small thing, Holmes' client talks of his father's obsession with "flying saucers." The story is indisputably set in the mid-to-late 1930s. Flying saucers did not become idiomatic vogue until after the war, in astonishing concert with the arrival of jet planes and rocketships. The anachronism vexed.

Still, it's the best story of the issue. A high three stars.

Though a Sparrow Fall, by Scott Nichols

One of those conversation pieces in which the story progresses in party dialogue. Turns out that the human genetic code has been written, or at least tampered with, such that a message has been buried within. By whom, and for whom, it is not known.

There's an interesting germ of a story here, almost something Theodore L. Thomas might address in his little column in F&SF. It doesn't really go anywhere, though.

Three stars.

Delivered with Feeling, by Lawrence A. Perkins

by Kelly Freas

At last, Mr. Perkins offers up another "lone man solves the problems of an alien world" story. This one deals with a planet whose disunion into dozens of profession-castes has made it easy prey for alien raiders. Because the invading planet and Earth are party to a mutual non-aggression pact, our protagonist can provide no material aid. Instead, he simply gives them a rallying slogan, which because of the unique qualities of the subjugated race, proves sufficient to throw off the alien onslaught.

The kicker, of course, is how the protagonist hatched his scheme. It's one of those technical puzzle stories that has been the stale bread and butter of the genre for decades. It's readable and forgettable.

Three stars.

A Dim Augury

Just one magazine cracked the three-star barrier this month: Fantasy and Science Fiction with 3.2 stars. IF and Science Fantasy were inoffensive three-star issues whilst (as Mark and Kris might say) New Worlds stumbled in at just 2.7. As this month's Analog scored a 2.8, it barely misses out on being the worst of the bunch.

And what a meager bunch it is! Without Galaxy and Worlds of Tomorrow (they're bimonthlies) and since the former Goldsmith mags, Amazing and Fantastic were on hiatus this month, there really wasn't much to read. Worse yet, there was just one woman-penned piece out of the 27 fiction stories published this month.

That the magazines were all fairly unremarkable, save perhaps for the unusually decent F&SF, just goes to show that even when the Sun God makes an appearance, it doesn't always herald good fortune.

Ah well. The Sun sets, but it also rises, and each day brings promise anew…

Sunrise, Roy Lichtenstein's latest masterpiece — see, this month wasn't all bad…

![[June 30, 1965] Every Day has its Dog (July 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650630cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 28, 1965] Heavyweight's Burden (June 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650528cover-663x372.jpg)

![[April 30, 1965] Back-door uprising(May 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650430cover-663x372.jpg)

![[March 30, 1965] Suborbital Shots (April 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650330cover-598x372.jpg)

![[February 28, 1965] Tragedy and Triumph (March 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650228cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 31, 1965] Janus, Facing Both Ways (February 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650131cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 31, 1964] Lost in the Desert (January 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/641231cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 29, 1964] All-star (December 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641129cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 30, 1964] The Deadly Barrier (November 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641030cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1964] Terrestrial Adventures (October 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641002cover-672x372.jpg)