[Kris Vyas-Myall and Cora Buhlert team up to cover two of the better Ace Doubles to have come out in a while. Enjoy!]

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

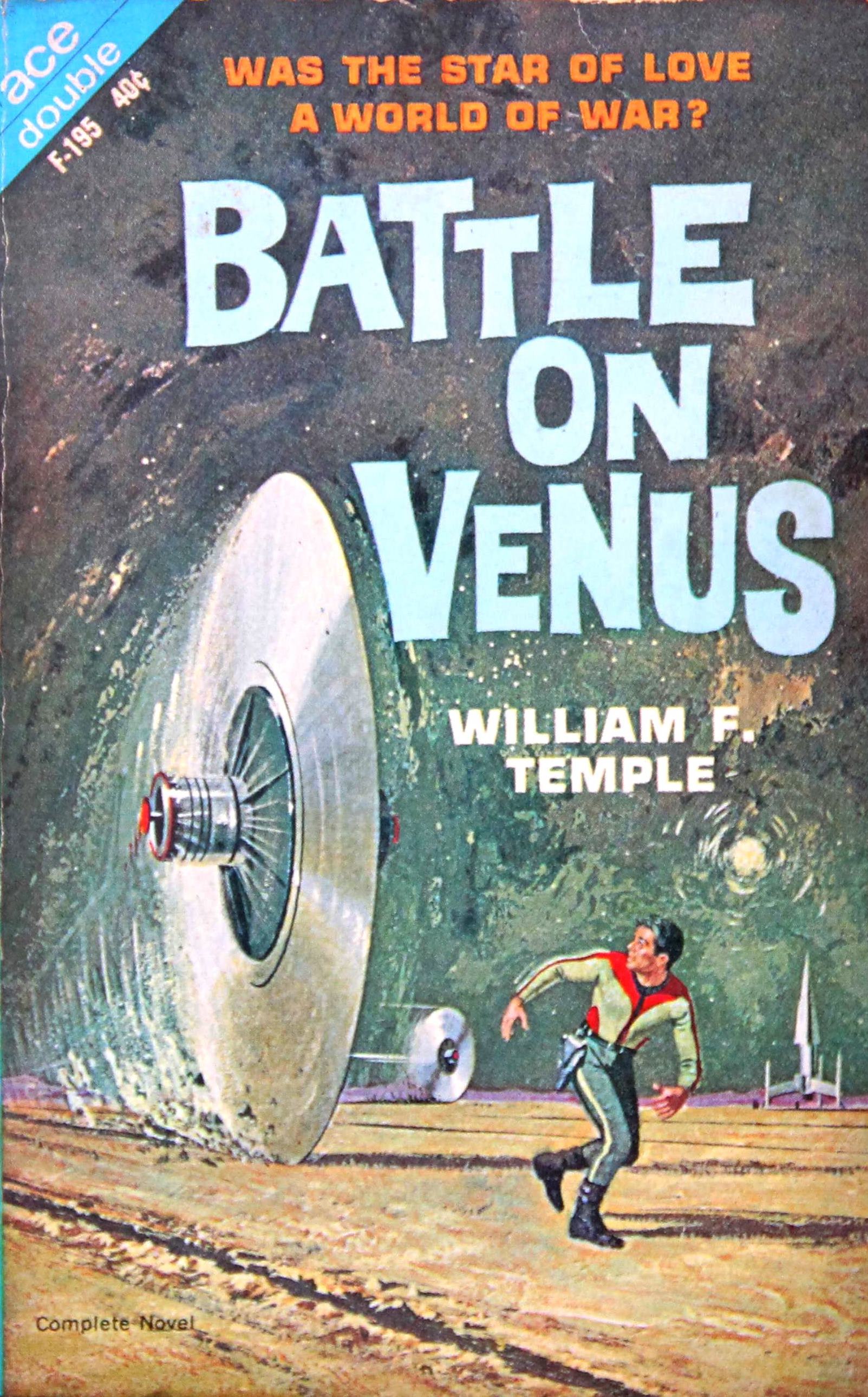

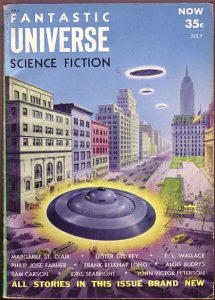

The Ballad of Beta-2, by Samuel R. Delany, and Alpha, Yes! Terra, no!, by Emil Petaja (Ace Double M-121)

I have generally been disappointed by the Ace Doubles so far this year. Those I have read have seemed to me to be quite old fashioned and I had been wondering if they were going to be heading into a more conservative route with them this year. Thankfully, this new Double I have found has been one of their best:

The Ballad of Beta-2 by Samuel R. Delany

I have been a fan of all four of Delany’s Ace novels, however I approached this with some excitement but also trepidation. For three of those former works were in the same Toron series and The Jewels of Aptor was also set in a similar post-catastrophe future. So, whilst I know he is an excellent writer I wondered how he would do with a generation starship story. I can definitively say he has not only succeeded but produced his best work to date.

This is an interesting take on the well-worn theme, where the generation starship became obsolete long before the crew reached their destination. The inhabitants found hyperdrive had resulted in the systems already being colonized and they themselves were outdated relics who were simply content to live on their ships. At the same time, it appears some form of reversion has taken place and those on board lack much of the knowledge they would have had at the start of the voyage.

Galactic anthropology student Joneny is forced to do an assignment on these Star Folk’s culture, specifically the titular “Ballad of Beta-2”. Originally Joneny assumes that the ballad is nothing but meaningless “cotton candy effusions”, but as he investigates further, he discovers this may hold the truth of what terrible fate befell the Star Folk on their long voyage.

This story starts off fairly leisurely and I assumed this was going to be a sedate academic kind of novel, travelling around exploring the starships. However, as it goes on you do discover that the terror listed on the front cover is justified, my heart pounding as I read some passages. And it should be said there are multiple unforeseen twists within its pages.

Delany clearly has a gift for poetry, with the ballad itself being a beautiful piece and with a clearer understanding of metre and imagery than may others in the fantasy field. He also uses a number of other clever literary devices which I loved, such as building up a mosaic story from framed narratives.

Throughout this Delany explores numerous interesting ideas. First is the value of the fantastic in storytelling and how easily it is dismissed by literary critics (something I am sure we have all seen).

Second is the problem of unchecked biases in academia. The only first-hand account Joneny can find is the original contact when the Star Folk entered the system and the Ballad was only picked up by sending in a robot to record, which the original anthropologist changed the lyrics he thought were clearly incorrect. It is off the back of this information that the common truth about the nature of the Star Folk is held.

Third is the danger of cultural assumptions. Thinking about who is civilized and what it truly means to be human. Throughout we are called on to challenge what we think we know and reassess that which we hold to be true.

Then this also acts as a reality check on the space romances, that see an ease to zipping around the universe, showing how hard this could really be. But then the story dives further into the dangers of anti-intellectualism and religious fundamentalism.

I could keep on about all the ways this work is fascinating. It should be noted this part of the Double is pretty short, only 96 pages, but within it he crafts a story with more depth than most writers manage in triple that time. And yet I would not say any of the concepts are treated at a surface level, he weaves it all together like a stout rope and you can see more ideas every time you look closer.

Needless to say, I fell in love with this short novel. I would recommend it for everyone, but it is not for the faint of heart or those looking for a light read. It is tough, intellectually challenging and really brutal at times.

Delany has once again proven himself to be one of the most exciting new voices in science fiction. If he is not to be my favourite writer of the year, someone else is going to have to produce something spectacular in the next six months!

Rating: Five Stars

Alpha Yes, Terra No! by Emil Petaja

Emil Petaja is an old hand of the genre but has been out of the writing game for almost a decade, only just beginning to sell new short stories and (I believe) this is his first novel. As such I was very curious what it would be like.

Humanity has fully conquered the Solar System and is preparing interstellar ships for further expansion. In Alpha Centauri they had been initially deflecting ships with their barrier, but the tribunal has decided it will be necessary to wipe out humanity completely.

The novel opens with an alien from Alpha Centauri arriving in San Francisco and ending up mingling with the homeless of the city. This person (who is initially called The Tourist but who will have more names as the story unfolds) has psychic powers and uses them to take a look at the differences in humanity and what life is like on Earth. However, his mission is not authorized, and a tracker has been sent to kill him.

Trying to summarize beyond this jumping on point seems like a fool’s errand as it become very complex. This story then evolves into a tapestry of life across the solar system, all of it linked together through a range of different characters, touching on ideas of power, mythology, belief and humanity.

Petaja makes a real effort to show what a future of ever-growing space colonization would be like rather than purely projecting the present into the future. This drive is leaving ordinary people’s lives in shambles as everyone has their eyes on space; crime and unemployment are rampant. Drug use is common. The natives of the planets that are being colonized are being exploited but it only manifests as power for a small number and as a means to fuel further expansion.

The author has an easily readable style which is useful as what he is doing could easily collapse under its own weight but somehow, he manages to juggle it. There were times when I would have to backtrack to check I was indeed following everything that was happening, but I never found myself becoming lost. I do think he could possibly have done more if this had been a full-length novel rather than squeezed down into one half of a Double, but he still works admirably with the page count he is given.

I expect this will be compared to Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land (although that itself is an old concept, dating at least as far back as Montaigne’s Of Cannibals) but it is really doing something different. This more a dialogue on humanity’s future weighing up the optimistic and pessimistic views we have emerging in science fiction and considering whether there is something worth saving in us.

So overall, Petaja’s return has proved to be a welcome surprise and I will be interested to see what he comes up with next. He clearly has a great affinity with Finnish myths, so perhaps a book based around that would be welcome?

Rating: Four Stars

by Cora Buhlert

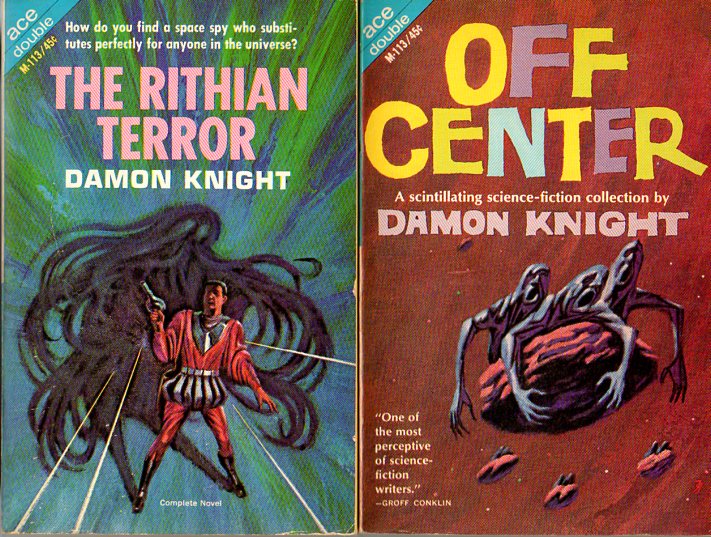

The Rithian Terror and Off Center by Damon Knight (Ace Double M-113)

Summer has come to West Germany, though you wouldn't know it by the wet and miserable weather we've been having.

Nonetheless, there are some good news. My hometown team Werder Bremen has won the West German football (soccer to our American friends) championship for the 1964/65 season.

The 83rd Kieler Woche, one of the biggest sailing regattas in the world, kicks off today in Kiel-Eckernförde. In addition to the sailing competition, there is also a parade featuring 23 tall ships from all over the world.

On to reading: In the spinner rack of my local import bookstore, I came across yet another Ace Double, No. M-113 to be precise. This one contained a novel as well as a short fiction collection by Damon Knight. In the past, I have enjoyed Damon Knight's works of literary criticism, so how would his fiction stand up?

Monster Hunt

Quite well, it turns out. The novel The Rithian Terror starts out with Security Commissioner Thorne Spangler, currently the most important official in the Earth Empire, on the hunt for a monster. That monster, the titular Rithian terror, is a tentacled horror that can take on the appearance of anybody it wishes. Seven Rithians came to Earth, but only one is still at large.

However, Spangler is certain he has the monster cornered. After all, there are house by house searches and roadblocks on every street, where everybody has to pass through a scanner. This is the one test a Rithian can't pass, for the scanner detects human skeletons and Rithians have none.

Spangler is accompanied by Jawj Pembun, an official from Manhaven, one of Earth's colony worlds, which recently gained its independence. Manhaven has regular contact with the Rithians, so Pumbun was brought in as an expert.

Spangler clearly resents Pembun's involvement in what should be his moment of glory. For starters, Pembun comes from a small backwater planet, one that only gained its independence, because the Earth Empire with its 260 planets let them. Furthermore, Pembun speaks in heavy dialect, while the Empire prizes precise language. Finally, Pembun is a black man, descended from African and Caribbean colonists, and Spangler is the sort of person who is very bothered by this and not shy about expressing it.

I have to admit that after the first fifteen pages or so, I came close to throwing the book against the nearest wall. There are enough racists in the real world, so I really don't need to spend time with racist characters while reading. However, I quickly realised that Knight was a better author than that. For even though Spangler may be the POV character, we're not meant to sympathise with him or his Empire. After all, Spangler and the Empire he serves are rigid, overorganised, xenophobic, have a massive superiority complex and are racist to boot. Spangler is also unpleasant in his personal life, a social climber who only courts his girlfriend Joanna because she is a member of a patrician family and will be useful to him. At one point, he even hits Joanna.

As a result, I quickly found myself sympathising with Pembun and cheered as he deflated Spangler and his smug compatriots. For starters, those scanners at every roadblock that Spangler is so proud of won't work, for while Rithians don't have skeletons, they could just swallow one to pass the test. Also, if the Empire wants to capture a Rithian alive, then maybe shooting six of the seven Rithians who crashlanded on Earth dead is not the best idea. Finally, Pembun casually drops the bombshell that the Rithians have hypnotic abilities as well as a nasty sense of humour.

A Game of Spies

What began as the hunt for an alien spy quickly turns into a game of cat and mouse between Spangler and Pembun. Spangler decides that Pembun must be a traitor and wastes a lots of resources trying to catch him redhanded. But the meeting of supposed offworld insurrectionists Spangler has his forces storm only turns out to be a Christmas party, where Pembun hands out gifts to children while dressed up as a legendary figure called the Grey Parrot.

While Spangler fails at every turn due to his rigid mindset, Pembun's unorthodox methods get results. And so Pembun manages to unmask the Rithian two thirds through the novel, using the Rithian's sense of humour against him. It turns out that the alien is posing as a junior member of the very committee dedicated to hunting him down. However, in the attempt to apprehend the Rithian, the alien is killed and Colonel Cassina, the military official the Rithian had hypnotised into giving him access to the security headquarters, is grievously wounded.

However, the crisis is not yet over. For the Rithians have planted bombs on Earth as leverage against the Empire. The key to the location of the bombs is in Colonel Cassina's head, only Cassina will not talk. And once Spangler's people finally manage to extract the message, destroying the Colonel's mind in the process, it turns out to be useless.

For Pembun points out that even though language has frozen and standardised in the Empire with every word having only a single meaning, it continued to evolve on the colony planets, where the same term can have many different meanings. So the location given in the message could be anywhere on Earth. Spangler and his security forces have no chance of locating the bombs. The Empire is finished, destroyed by its own rigidity, and so is Spangler's career. However, Spangler and Pembun have developed a grudging respect for each other and Pembun offers him a place on his homeworld Manhaven. Spangler's girlfriend Joanna, who up to now had refused to marry him, knowing fully well that Spangler wanted her not for herself, but for her position, agrees to go with him.

A Tale with Multiple Meanings

As a linguist, I enjoyed that the solution to the central mystery of the novel lies in the ambiguity of language. Another thing I liked was that Pembun's native tongue, which he occasionally speaks throughout the novel, is a Creole based on French, Spanish and English. I have no idea if Knight used a real Creole language, but it certainly feels convincing enough.

Just like the solution of the linguistic mystery, The Rithian Terror is a novel with multiple layers and meanings. On the surface, it is a hunt for a literal bug-eyed monster that has infiltrated Earth. However, it is also a John Le Carré like spy novel about two agents, both nominally on the same side, trying to outmanoeuvre each other. Finally, The Rithian Terror is a novel about colonialism and the slow decline and death of empires.

It is this last aspect that is also the most topical, for in the past fifteen years, we have seen the once great colonial empires of Britain and France as well as smaller powers like Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain and Italy slowly fall apart, as more and more nations in Africa, South East Asia and the Caribbean gain independence. And it is certainly no accident that Pembun, the representative of a newly independent world, is also a black man speaking Creole, while his counterpart Spangler is an overly rigid white man with the proverbial stick shoved up his backside. Knight makes it very clear to which of these two very different men the future belongs.

Four stars.

Off Center

Of Immigrants and Dolpins

Off Center, the second half of this Ace Double, is a collection of five pieces of short fiction originally published between 1952 and 1964.

The first story "What Rough Beast?" is the story of a young immigrant named Mike Kronski trying to make his way in America. However, Mike is not the simple East European immigrant he appears to be. He comes from far further afield, from an alternate universe. He also has the ability to bend reality to his will and has accidentally changed his world into ours.

The first story "What Rough Beast?" is the story of a young immigrant named Mike Kronski trying to make his way in America. However, Mike is not the simple East European immigrant he appears to be. He comes from far further afield, from an alternate universe. He also has the ability to bend reality to his will and has accidentally changed his world into ours.

Through a series of misadventures, Mike meets a young woman called Anne with burn scars on her body. He uses his ability to heal Anne's scars, which causes Anne's father and a greedy friend to capture Mike to exploit him. Mike tries to run away and is shot. In his terror, he accidentally erases New York from existence. Only Anne remains. Mike takes her to a different version of New York, where she can feel at home, and then departs to a new reality, hoping that this time, he will fit in.

A touching tale about the alienation and profound sense of homesickness many immigrants feel. Knight captures Mike's voice and his imperfect English well. Our editor Gideon Marcus also loved the story.

"Second Class Citizen" is the story of researcher Charles Craven and the subject of his studies, the dolphin Pete. Craven has taught Pete to understand and speak English, spell simple words and even do chemical experiments. While Craven patronisingly presents Pete to some visitors, we learn from background conversations that there is an international crisis going on. Craven is convinced that this crisis will blow over, like any other crisis before.

"Second Class Citizen" is the story of researcher Charles Craven and the subject of his studies, the dolphin Pete. Craven has taught Pete to understand and speak English, spell simple words and even do chemical experiments. While Craven patronisingly presents Pete to some visitors, we learn from background conversations that there is an international crisis going on. Craven is convinced that this crisis will blow over, like any other crisis before.

However, Craven is wrong, for shortly after the visitors have left, the TV program is interrupted for a special bulletin before dropping out altogether. Craven correctly deduces that war has begun and manages to dive to the underwater station of his research base just before heat bombs fall all around him. Craven survives the attack, but once his food runs out, he will be doomed, unless he manages to catch enough fish to survive. However, Craven has no idea how to catch fish. Then Pete appears, easily catching the fish. The roles are reversed now, the teacher has become the student.

An interesting story about the way humans treat animals, but too short to make much of an impact. Gideon Marcus feels the same in his review of the story.

Of Ghosts, Gods and Martians

The novella "Be My Guest" is the story of Kip Morgan, a young man who finds himself possessed by four bickering ghosts after a poisoning attempt gone wrong. Kip also has another problem, he as well as two women of his acquaintance have become invisible to everybody but each other.

The novella "Be My Guest" is the story of Kip Morgan, a young man who finds himself possessed by four bickering ghosts after a poisoning attempt gone wrong. Kip also has another problem, he as well as two women of his acquaintance have become invisible to everybody but each other.

The novella follows Kip through his increasingly desperate attempts to get rid of his unwanted tenants and solve his invisibility problem. Kip finally realises that everybody had multiple ghosts living inside them and that these ghosts influence their decisions. He also realises that his invisibility problem is a form of quarantine to keep Kip from talking about the ghosts. Eventually, he blackmails some very powerful ghosts inhabiting the body of a rich man into lifting the quarantine and make sure that he and the two women are given only beneficial and helpful ghosts. Finally free, Kip also realises that the woman he thought he loved is not the person who's really good for him.

"Be My Guest" is an fascinating attempt at a science fictional ghost story. Knight viscerally conveys Kip's growing desperation. It does feel a little long, though, and would probably have worked better as a novelette or short story.

"God's Nose" is a short vignette that does exactly what it says on the tin. The unnamed narrator and his female friend debate what the nose of God would look like. Eventually, her lover Godfrey arrives. He has a very prominent nose.

"God's Nose" is a short vignette that does exactly what it says on the tin. The unnamed narrator and his female friend debate what the nose of God would look like. Eventually, her lover Godfrey arrives. He has a very prominent nose.

Inconsequential without much in the way of plot or point.

The final story "Catch That Martian" feels very much like a mix between The Rithian Terror and "Be My Guest". Once again, we have a dangerous alien, the titular Martian, who can take on the appearance of any human being. And once again, we have people abruptly taken out of the real world and turned into "ghosts". A young police officer is determined to crack the mystery of the ghosts and catch the Martian in the act. He deduces that the ghosts must have annoyed the Martian somehow, mostly via making noise, and that the Martian has a taste for musical theatre. So the narrator traces the Martian to a Broadway theatre, determined to apprehend him. But before he can give chase, he falls into the orchestra pit, straight onto a bass drum.

The final story "Catch That Martian" feels very much like a mix between The Rithian Terror and "Be My Guest". Once again, we have a dangerous alien, the titular Martian, who can take on the appearance of any human being. And once again, we have people abruptly taken out of the real world and turned into "ghosts". A young police officer is determined to crack the mystery of the ghosts and catch the Martian in the act. He deduces that the ghosts must have annoyed the Martian somehow, mostly via making noise, and that the Martian has a taste for musical theatre. So the narrator traces the Martian to a Broadway theatre, determined to apprehend him. But before he can give chase, he falls into the orchestra pit, straight onto a bass drum.

Well written and Knight once again captures the distinctive voice of his first person narrator perfectly. However, the story is also slight and a little silly, particularly compared to the two similar stories in this Ace Double.

All told, Off Center is a nice collection that showcases Knight's writing skills, even though some of the stories are a little slight.

Three stars.

[Don't miss the next episode of The Journey Show, featuring singer-songwriter Harry Seldon. He'll be playing a mix of Dylan, Simon, and some unique original compositions!]

![[June 20, 1965] Ace Quadruple (June Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650620cover-397x372.jpg)

![[February 26, 1965] Dare to be Mediocre (February Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650226covers-655x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1965] Madness: 2, Sanity: 1 (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650104covers-672x372.jpg)

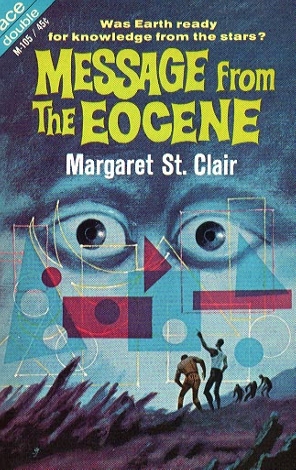

![[December 11, 1964] December Galactoscope](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/message_from_the_eocene-296x372.jpg)

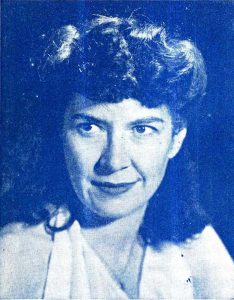

In "The Everlasting Food", Earthman Richard Dekker finds that his Venusian wife Issa has changed after lifesaving surgery. One night, Issa announces that she is immortal now, that she no longer needs to eat and that energy sustains her. Soon thereafter, she leaves, taking their young son with her. Richard takes off after her to get his son back, Issa's human foster sister Megan in tow. After many trials and tribulations, they finally find Issa – only for Richard to lose his wife and son for good. But while Richard is heartbroken, he has also fallen in love with Megan.

In "The Everlasting Food", Earthman Richard Dekker finds that his Venusian wife Issa has changed after lifesaving surgery. One night, Issa announces that she is immortal now, that she no longer needs to eat and that energy sustains her. Soon thereafter, she leaves, taking their young son with her. Richard takes off after her to get his son back, Issa's human foster sister Megan in tow. After many trials and tribulations, they finally find Issa – only for Richard to lose his wife and son for good. But while Richard is heartbroken, he has also fallen in love with Megan. "Idris' Pig" opens on a spaceship to Mars. George Baker is the ship's resident psychologist. His cousin Bill is a courier and passenger aboard the same ship. When Bill falls ill, it's up to George to deliver the object Bill was supposed to deliver, a blue-skinned sacred pig. However, Bill can only give George very vague instructions about where to deliver the pig and so the pig is promptly stolen. And so George has to retrieve it with the help of Blixa, a young Martian woman. As a result, George gets mixed up with drug dealers and Martian cults, involved in an interplanetary incident and lands in jail. He also completely forgets about the woman he has been trying very hard not to think about and falls in love with Blixa.

"Idris' Pig" opens on a spaceship to Mars. George Baker is the ship's resident psychologist. His cousin Bill is a courier and passenger aboard the same ship. When Bill falls ill, it's up to George to deliver the object Bill was supposed to deliver, a blue-skinned sacred pig. However, Bill can only give George very vague instructions about where to deliver the pig and so the pig is promptly stolen. And so George has to retrieve it with the help of Blixa, a young Martian woman. As a result, George gets mixed up with drug dealers and Martian cults, involved in an interplanetary incident and lands in jail. He also completely forgets about the woman he has been trying very hard not to think about and falls in love with Blixa. "The Rages" is set in an overmedicated Earth of the future. Harvey has a perfect life and a perfect, though sexless marriage. However, he has a problem because his monthly ration of euphoria pills has run out. And without euphoria pills, Harvey fears the oncoming of the rages, attacks of uncontrollable anger, which eventually lead to a final rage from which one never emerges. The story follows Harvey through his day as he meets several people and tries to get more pills. Gradually, it dawns upon both Harvey and the reader that the pills may be causing the very rages they are supposed to suppress. The story ends with Harvey throwing all of his and his wife's pills away.

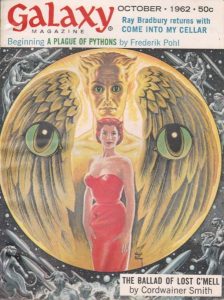

"The Rages" is set in an overmedicated Earth of the future. Harvey has a perfect life and a perfect, though sexless marriage. However, he has a problem because his monthly ration of euphoria pills has run out. And without euphoria pills, Harvey fears the oncoming of the rages, attacks of uncontrollable anger, which eventually lead to a final rage from which one never emerges. The story follows Harvey through his day as he meets several people and tries to get more pills. Gradually, it dawns upon both Harvey and the reader that the pills may be causing the very rages they are supposed to suppress. The story ends with Harvey throwing all of his and his wife's pills away. "Roberta" is the shortest and most recent story, first published in Galaxy in October 1962,

"Roberta" is the shortest and most recent story, first published in Galaxy in October 1962,  In "The Island of the Hands", Dirk dreams about his wife Joan who died in a plane crash at sea. He hires a plane to check out the coordinates from his dream and crashes on an invisible island. Dirk finds Joan's plane and a dead body and also meets Miranda, a young woman who suspiciously resembles Joan. He is on the Island of the Hands, Miranda informs them, where everybody can shape their heart's desire from mythical mist. Dirk tries to shape Joan, but fails. He spends the night with Miranda, who confesses that Joan is still alive, but trapped in the mist. Dirk goes after her and rescues Joan, only to learn that there is a very good reason why Miranda looks so much like an idealised version of Joan.

In "The Island of the Hands", Dirk dreams about his wife Joan who died in a plane crash at sea. He hires a plane to check out the coordinates from his dream and crashes on an invisible island. Dirk finds Joan's plane and a dead body and also meets Miranda, a young woman who suspiciously resembles Joan. He is on the Island of the Hands, Miranda informs them, where everybody can shape their heart's desire from mythical mist. Dirk tries to shape Joan, but fails. He spends the night with Miranda, who confesses that Joan is still alive, but trapped in the mist. Dirk goes after her and rescues Joan, only to learn that there is a very good reason why Miranda looks so much like an idealised version of Joan.

![[September 20, 1964] Apocalypses and other trivia (Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/penultimate-cover-672x352.jpg)

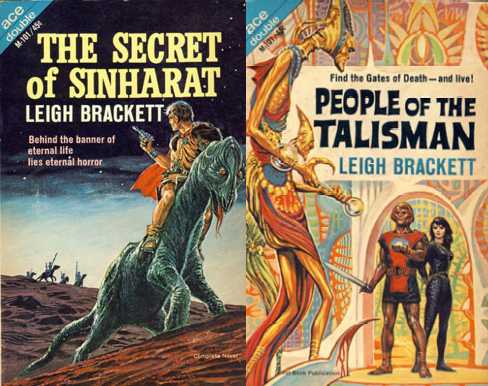

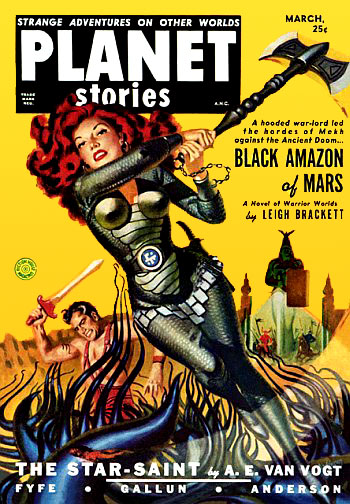

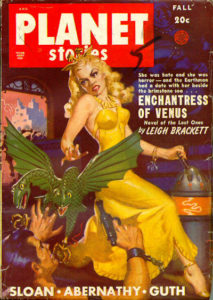

![[August 11, 1964] Leigh Brackett Times Two: The Secret of Sinharat and People of the Talisman (Ace Double M-101)](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Planet_Stories_March_1951_cover-350x372.jpg)

Though upon closer examination

Though upon closer examination

Of course, there are also differences. The Valley of Creation is set on Earth, in a hidden valley in the Himalaya, while The Secret of Sinharat is set on Mars. And Eric John Stark is a much more developed and interesting character than the rather bland Eric Nelson. Nonetheless, the parallels are striking. Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett are not known to collaborate like C.L. Moore and her late husband Henry Kuttner did. But given the similarities of both stories and the fact that they were written around the same time, I wonder whether Brackett and Hamilton did not both write their own version of the same basic idea.

Of course, there are also differences. The Valley of Creation is set on Earth, in a hidden valley in the Himalaya, while The Secret of Sinharat is set on Mars. And Eric John Stark is a much more developed and interesting character than the rather bland Eric Nelson. Nonetheless, the parallels are striking. Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett are not known to collaborate like C.L. Moore and her late husband Henry Kuttner did. But given the similarities of both stories and the fact that they were written around the same time, I wonder whether Brackett and Hamilton did not both write their own version of the same basic idea.

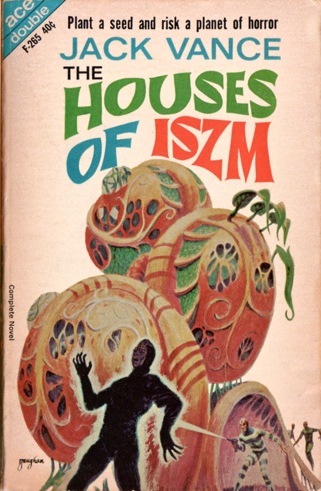

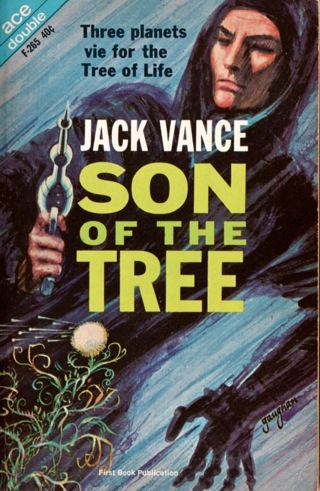

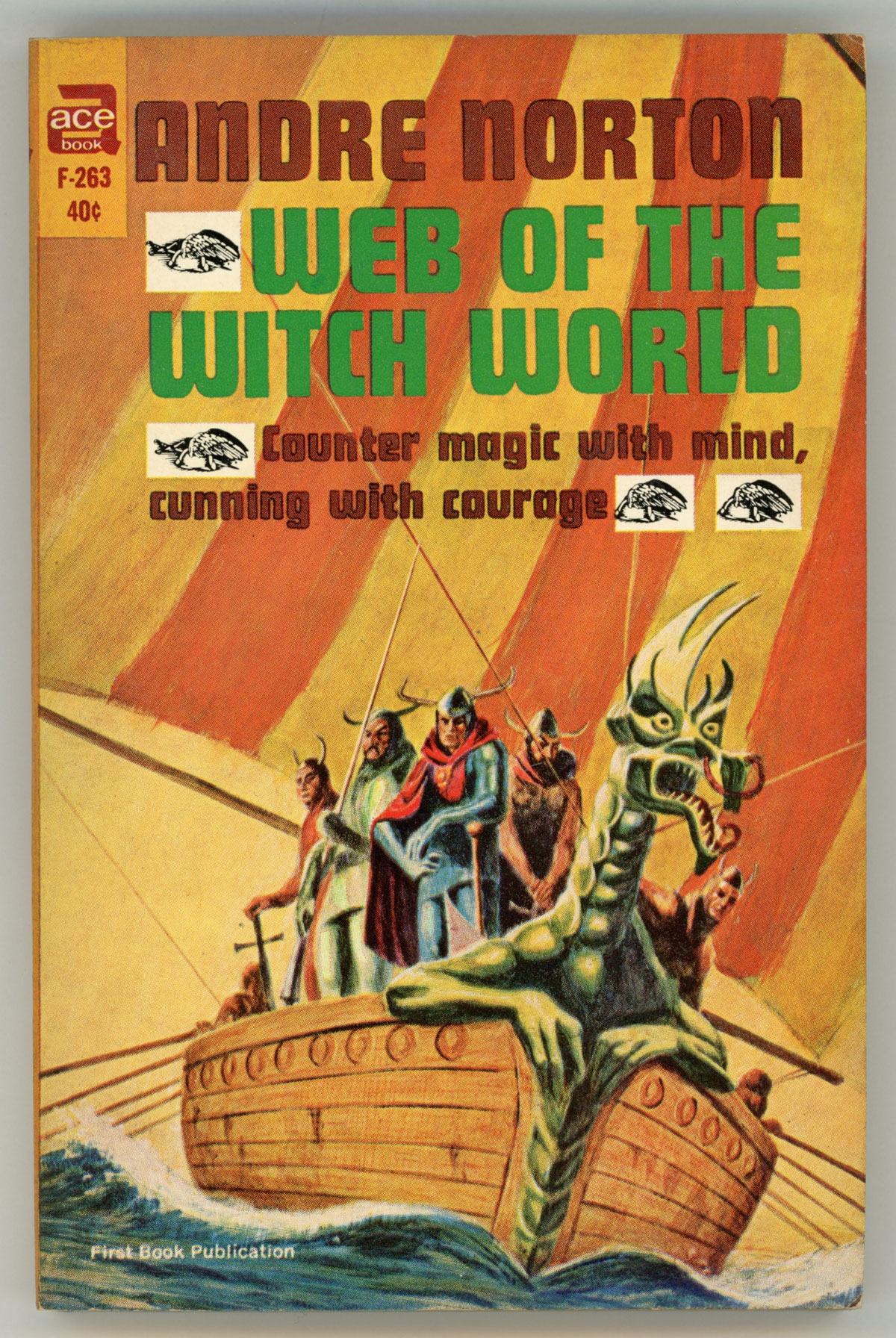

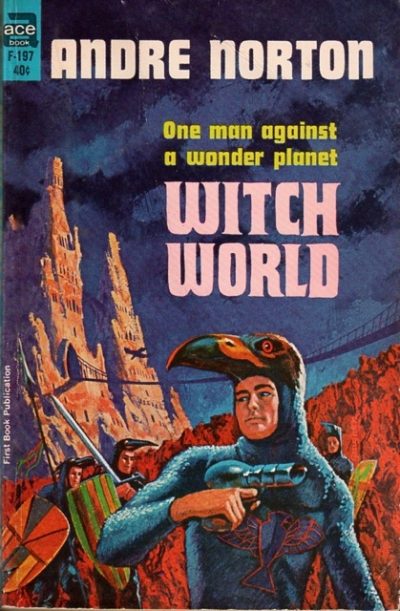

![[April 16, 1964] Of Houses and World Building (Jack Vance's The Houses of Iszm/ Son of the Tree and Andre Norton's Web of the Witch World)](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640416double-640x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1964] Something borrowed, something blue (Ace Double F-253)](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/640106f253-1-672x372.jpg)

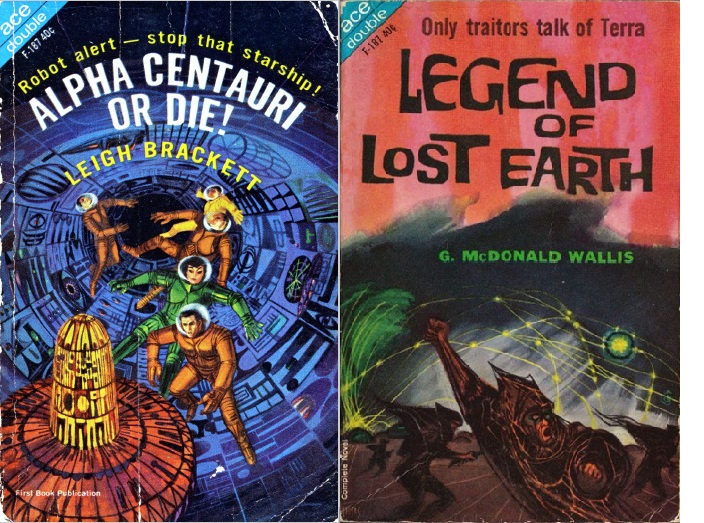

![[November 17, 1963] Galactoscope (Three Ace Doubles!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631117f187-672x372.jpg)