Books seem to be published faster than ever these days, and many are worth a gander. Please enjoy this triple-whammy featuring SEVEN sciencefictional titles…plus a surprise guest at the end!

by Gideon Marcus

Nightwalk, by Bob Shaw

Shaw recently made a big impact with his Hugo-nominated short story, Light of Other Days, and I've enjoyed everything he's come out with. So it was with great delight that I saw that he'd come out with a full length novel called Nightwalk.

I went in completely blind, and as a result, enjoyed the twists and turns the story took far more than if I'd known what was coming. Thus, I give you fair warning. Avoid the following few paragraphs if you wish to go into the book completely unaware.

by Frank Frazetta

Sam Tallon is an agent of Earth based on the former colony and now staunch adversary world, Emm Luther. In-between are 80,000 portals through null-space. Would that there could be but one, but hyperspace jumping is a blind affair, and the direct route between portals is impossible to compute. Only trial and error has mapped 80,000 matched pairs whose winding, untrackable route bridges the two worlds. Luckily, transfer is virtually instantaneous.

Literally inside Tallon's head is the meandering route to a brand new world. Given the dearth of inhabitable planets, both overcrowded Luther and teeming Earth want this knowledge. Before Tallon can escape with it, he is captured by the Lutheran secret police, tortured most vividly and unpleasantly, and sent for a life sentence to be spent at the Lutheran version of Devil's Island, the Pavillion.

Oh yes–in an escape attempt, the sadistic interrogator whom Tallon fails to kill on his way out zaps his eyes and leaves him quite blind.

Tallon is not overly upset by this development. At this point. he is quite content to spend the rest of his life in dark but not unpleasant captivity…except the wounded interrogator is coming for a visit, and Tallon knows he won't survive the encounter. Luckily, he and a fellow prisoner have managed to create a set of glasses tied into the optic nerve and tuned to nearby glial cells. They will not restore a man's sight…but they will allow him to tune in to the vision of any animal about him. With this newfound advantage, Tallon must make the thousand mile trek back to the spaceport, and then traverse the 80,000 portals to Earth.

Alright–you can read again. Nightwalk is 160 pages long. 60 of the pages, the first 30 and the last 30, are brilliant, nuanced, full of twists and turns, and genuinely exciting. The 100 pages inbetween comprise a well-written but forgettable thriller. I will not go so far as to agree with Buck Coulson, who wrote in the latest Yandro: "pulp standard; described by Damon Knight as "putting his hero in approximately the position of a seventy-year-old paralytic in a plaster cast who is required to do battle with a saber-tooth tiger and there being no place to go from there, kept him in the same predicament throughout the story, only adding an extra fang from time to time." But the assessment is not completely inapt.

Nevertheless, the book kept me reading, and if you can keep momentum through the middle, the whole is worthwhile.

3.5 stars.

ACE double H-34

Another month, another "ACE double". They seem to increasingly becoming my province these days, or perhaps I'm becoming the resident Tubb novel reviewer. Either way, I'm thoroughly amenable to the relationship!

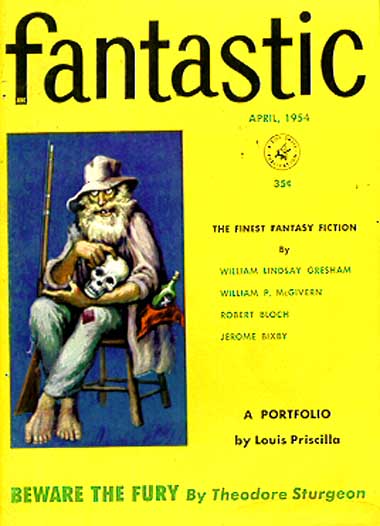

Computer War, by Mack Reynolds

Cover by Hoot von Zitzewitz

I originally covered this novel when it appeared in the pages of Analog. Long story short: it's a history lesson disguised as an SF story–Reynolds doesn't even bother to color his nations, which retain their stock names of Alphaland and Betastan, as if this were an Avalon Hill wargame or something.

Not one of his better efforts, and it doesn't even have the benefit of Freas' nice art. A low three stars.

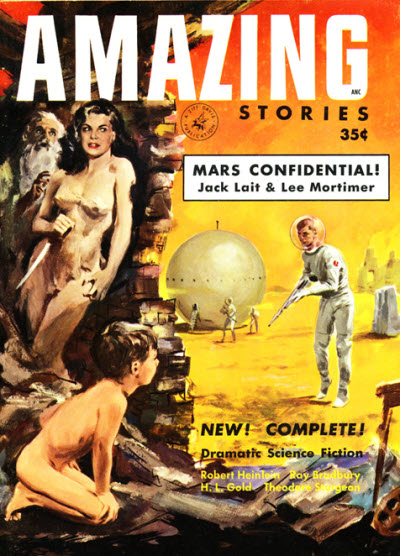

Death is a Dream, by E.C. Tubb

Cover by Rob Howard

Three centuries from now, England is still recovering from "the Debacle", an atomic paroxysm that all but destroyed the world in the 1980s. Society has calcified into an oligarchic, capitalist nightmare, with a few rich entities ultimately controlling everything: the loan sharks, the power generators, and the hypnotists. In many ways, it is the last group that is the most powerful, for a generation after the Debacle, they fostered a pervasive belief in reincarnation. With their guidance (or perhaps suggestion), all (save the rare odd "cripple") persons can Breakthrough to their past lives). So universal is this belief in multiple lives that many have become "retrophiles", living out their lives in the guise of a former existence, even to living in towns constructed along archaic lines.

Into this world are thrust three bonafide time travelers, put in stasis in the 1970s to await a cure for their radiation-caused illnesses. Not only are they exiles in an age not theirs, but they have also amassed a tremendous debt in their centuries asleep. Brad Stevens, an atomic physicist born in 1927, is determined to free himself and his 20th Century comrades from the fetters of financial obligation. Thus ensues a rip-roaring trip through an anti-utopian Britain, filled with narrow escapes, exotic scenery, and a few interesting, philosophical observations.

Tubb has already impressed me this year with his vivid The Winds of Gath, and he does so again with this adventure. Indeed, Tubb is such the master of the serial cliff-hanger that I found myself quite unable to put the book down, reading it in two marathon sessions. Of particular note are his observations on faith, on the seductiveness of nostalgia, and on the pernicious nature of laissez-faire capitalism, which inevitably degenerates into anything but a free market.

What keeps this story from a fifth star is precisely what garners it a fourth: it is quick, excellent reading, but it doesn't pause long enough to fully explore all of its intriguing points. Thus, it remains like Ted White's Jewels of Elsewhen–beautifully turned, but somewhat disposable.

Still, I'm not sorry I read it, and neither will you be. Four stars.

by Victoria Silverwolf

From the L File

Two new science fiction novels with titles that begin with the twelfth letter of the alphabet fell into my hands recently. Other than that trivial coincidence, they could hardly be more different. Let's look lingeringly, lest literature lie listlessly languid.

Lords of the Starship, by Mark S. Geston

Cover art by John Schoenherr

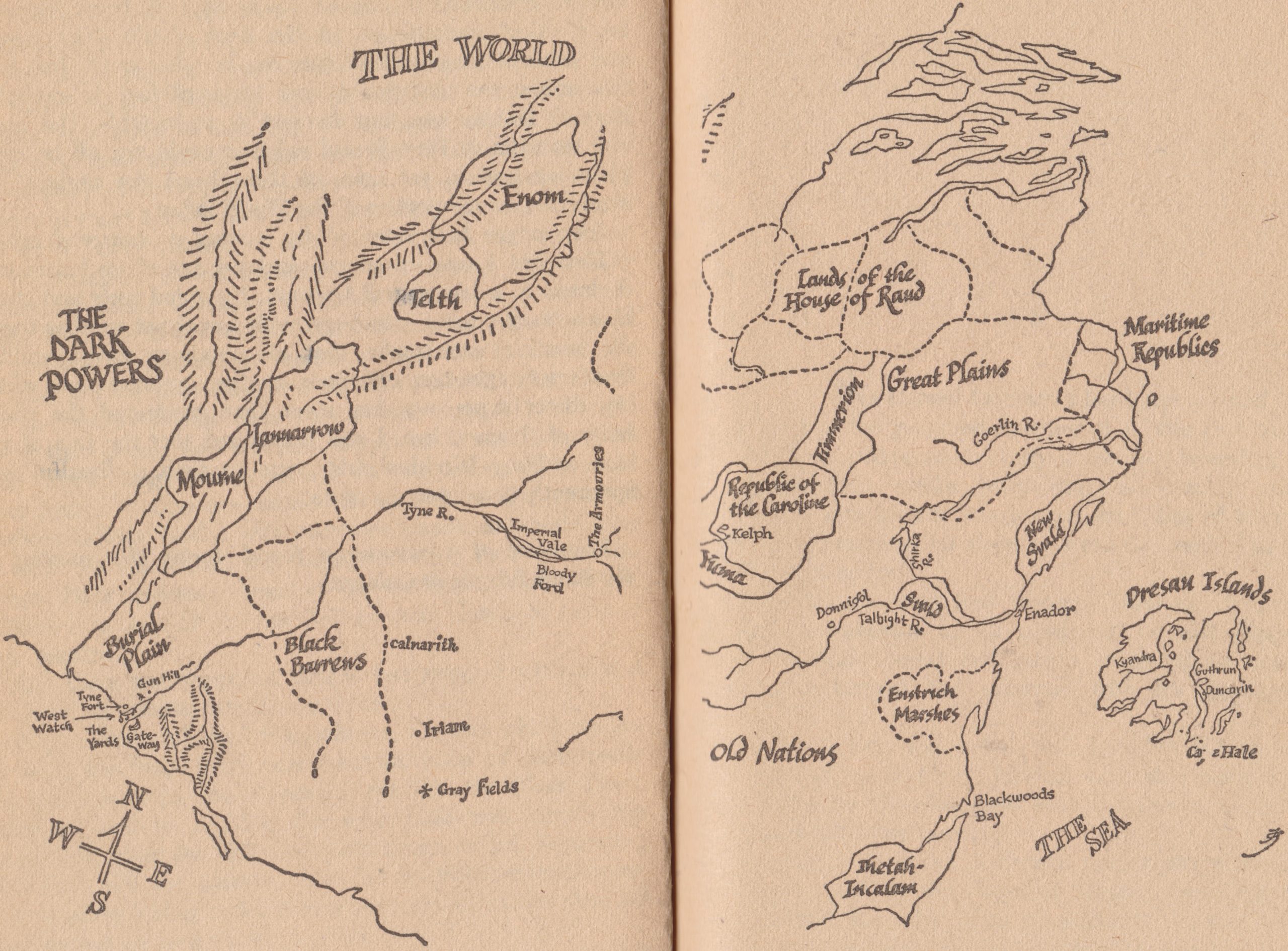

The first thing you'll notice when you open the book is a map. With that, and the title, I wonder if the author and/or the publisher is alluding to J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy trilogy The Lord of the Rings, which has recently become quite popular here in the USA. That series has a map too.

Map by Jack Gaughan

Given the size of a paperback, it's darn hard to see everything on the map, which has a lot of detail. Fortunately, it's not really necessary. I'll point out a few landmarks as we go along.

A Public Works Project

We start in the middle of the map. At first, you might think the novel takes place in the past, with horse-drawn vehicles and such. We soon find out that it's thousands of years in the future. Our own technological society is nearly mythical, lost in the mists of time. There are bits and pieces of it here and there, left in ruins.

It seems that humanity lost its spirit long ago. Civilization has stagnated. A military officer has a plan to deal with that, and he explains it to a government official.

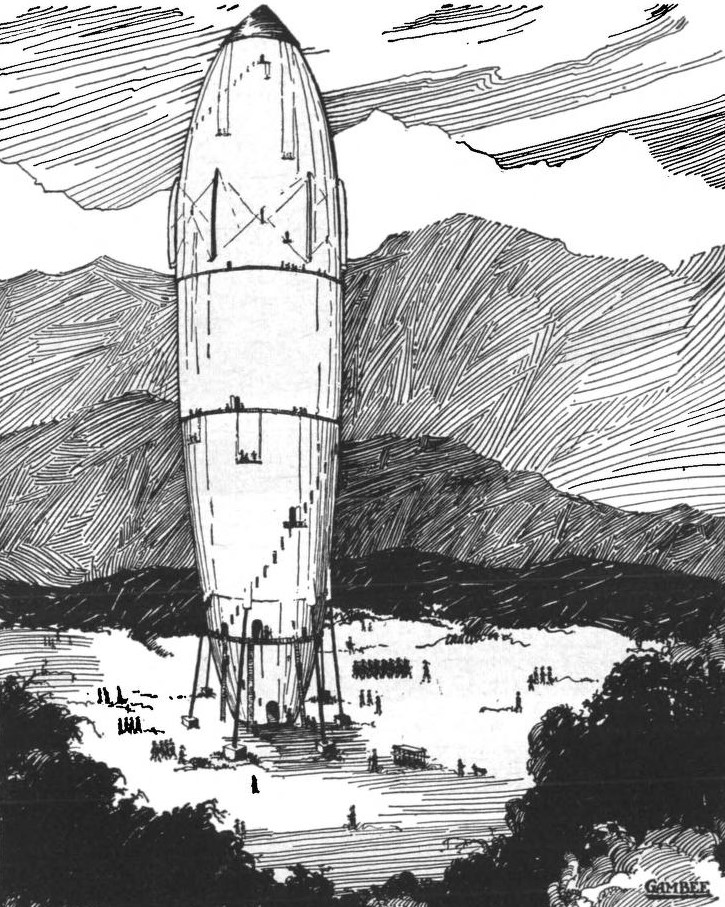

Take a look at the extreme southwest corner of the map, right next to the compass. That's a place where gigantic remnants of the glory days of yesteryear lie wasting away. The officer's scheme is to build a huge starship from what's left and carry its passengers to a new, better world.

If that sounds crazy to you, you're on the right track. There is no real intent to complete the project. Instead, it's just a trick to get the population excited about something, and working together for centuries. Think pyramids and cathedrals.

The first step is to launch a series of bloody wars, so the folks in the middle of the map can make their way to the coast, conquering and slaughtering along the way. Make no mistake; there are a lot of gruesome battle scenes in this book.

Many years later, society is divided into a small number of elites, who know the truth about the phony starship, and the ordinary people, who do not. The latter come to almost worship it. Under the leadership of a charismatic figure, they revolt against their rulers.

We're still not done with bloodshed. Without going into details, suffice to say that the naval fleets of the islands off the eastern coast (look at the map) get involved. This leads to a conflict that makes everything else that happens in the book look like minor skirmishes. Then we get a wild twist ending that really pulls the rug out from under you, making you rethink everything you thought you knew about what's going on.

This is a strange book. There are no real protagonists. The plot takes place over a couple of centuries or so, and characters come and go very quickly. This accelerates in the latter part of the novel. Some chapters consist of only one sentence, and read like excerpts from a history book. (The author is a history major, still in college.)

It's also a dark and cynical book. From the deception that starts the story to the completely unexpected revelation that ends it, it's full of sinister plots, secretive government agencies, and human lives sacrificed for the schemes of others.

A sense of despair and resignation to fate fills the novel. The commander of the naval fleet I mentioned above knows that building up his ships for the upcoming war will take eighty years, and also knows that wholesale destruction will be the outcome of the conflict, but accepts the situation as inevitable.

It's an intriguing work, but one that's very hard to love.

Three stars

Logan's Run, by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson

Cover art by Mercer Mayer

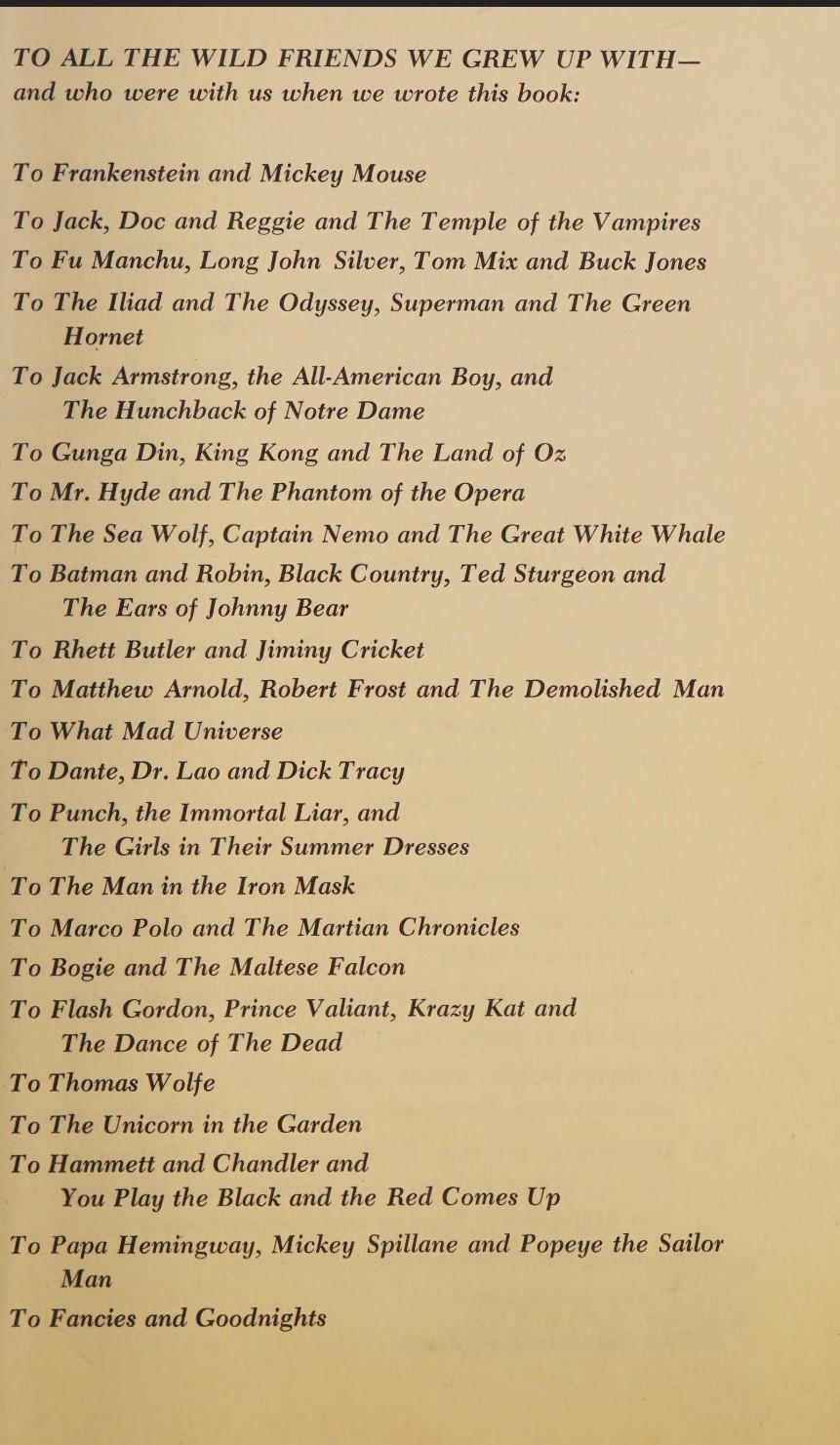

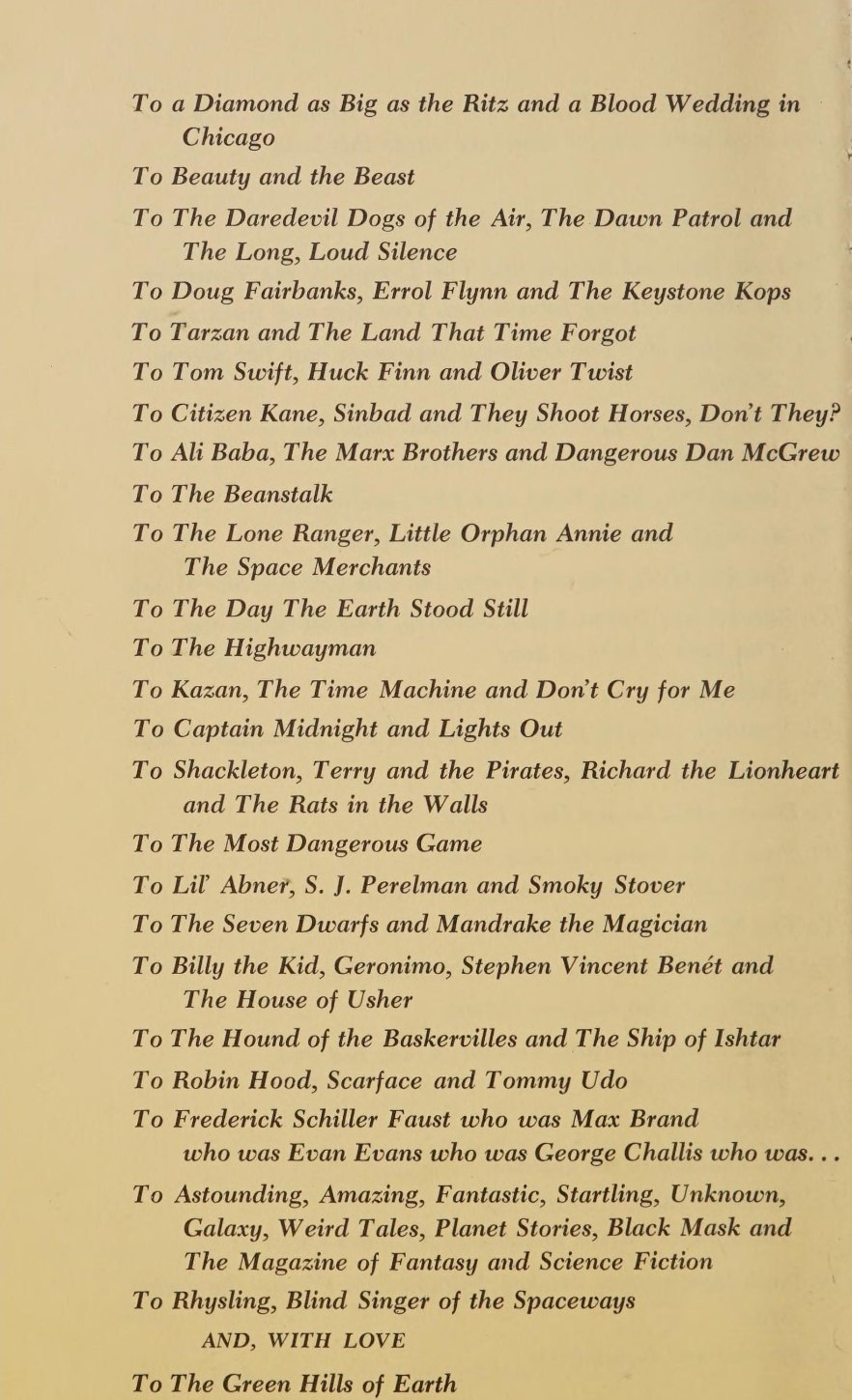

There's no map in this book, but it does have what must be the world's longest dedication. See for yourself.

I don't recognize everything on that massive list — The Ears of Johnny Bear? — but I am familiar with much of it. What do those things have in common? Unless I am mistaken, none of them are very recent. Keep that in mind.

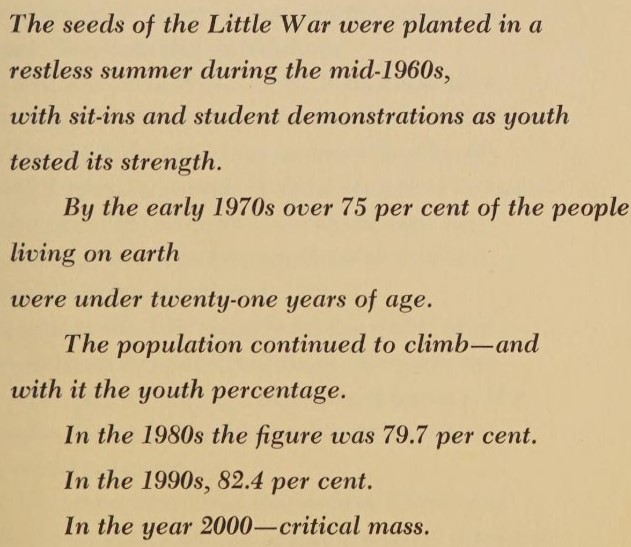

Next we get the book's basic premise.

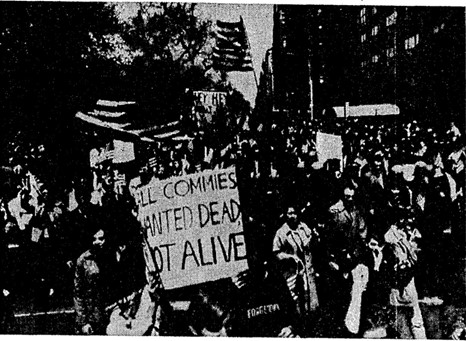

I get the message. It's that darn Youth Culture everybody is talking about. I suppose that's because a lot of post-World War Two babies are in their teens and early twenties now. Mods, hippies, bikers, protestors; they're all young folks, aren't they? The two authors of this novel don't seem too happy about the situation.

Don't Trust Anyone Over Twenty-One

(Apologies to political activist Jack Weinberg for stealing and distorting his famous quote. The original number was thirty.)

Something like a century and a half from now, people are only allowed to live to the age of twenty-one. We get an explanation late in the book as to how this happened, but never mind about that. Most folks go along with this, but some try to escape. These rebels are called — you guessed it — Runners.

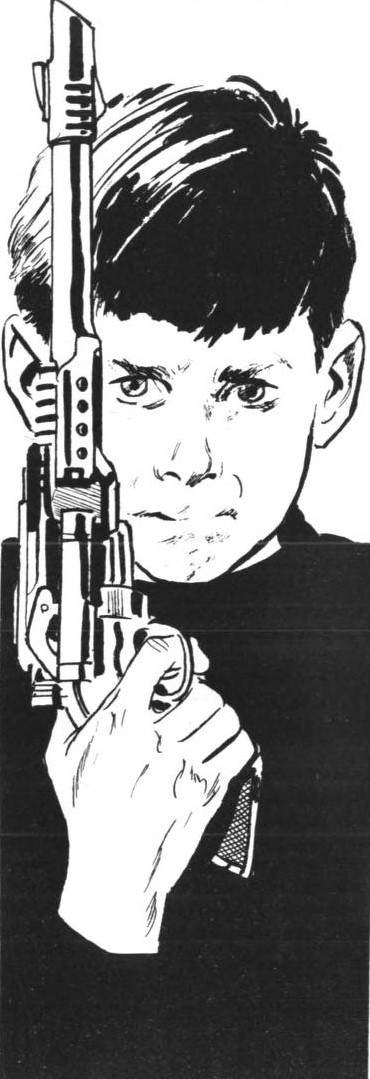

There's a special police force that kills Runners. They're known as Sandmen. Our hero, Logan 3, is a Sandman near the end of his assigned lifetime. He gets a gizmo from a dying Runner that is supposed to lead the person who holds it to the fabled refuge known as Sanctuary. Determined to find and destroy the place, he pretends to be a Runner himself. The dead man's sister, Jessica 6, is also a Runner. You won't be surprised to find out she's the love interest, too.

Most of the book consists of the pair's wild adventures all over the world as they try to find Sanctuary. Feral children in a decaying part of a city; an inescapable prison at the North Pole; rebellious young folks who ride around on what seem to be flying motorcycles; robots recreating a Civil War battle; and much, much more. The plot moves at an insane pace, and you probably won't believe a minute of it.

Meanwhile, a Sandman named Francis 7 tracks down the two. He's kind of like Inspector Javert from Victor Hugo's novel Les Miserables or Lieutenant Gerard from the TV series The Fugitive. Cold-blooded and relentless, he never gives up. He's also got a secret of his own, leading to a surprise ending.

I get the feeling that the co-authors threw wild twists and turns at each other, shouting Top This! as they tossed pages of the manuscript back and forth at each other. It's a wild ride indeed. As I've indicated, it's got a lot of implausible aspects. The one that really stood out for me was when Logan and Jessica instantly — and I mean instantly — fall in love when they pose nude for a ice sculpture carved by a half-man/half-robot. (Long story.)

If you like lightning-paced action/adventure novels with a touch of satire, you'll get some fun out of this one. Just don't expect serious speculation about where the younger generation is taking us older folks.

Three stars.

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

Not Quite What We Were Tolkien About!

Whilst it has been delayed by the legal shenanigans around the paperback edition of The Lord of The Rings, we are going to be getting the next installment in Tolkien’s Middle Earth series, The Silmarillion, very soon. Cylde S. Kilby was helping Professor Tolkien over the summer and gives some details in a recent edition of The Tolkien Journal, including that this is going to borrow a lot from Norse Myths around the creation of Midgard. Sounds like an epic and complex work for sure.

However, in the meantime, we have a new tale from him, not related to Middle Earth. In some ways, it is a more traditional fairy story, but with many fascinating elements that make it well worth your while.

Smith of Wootton Major by J. R. R. Tolkien

Every twenty-four years, in the village of Wootton Major, there is held the feast of Twenty-Four where a great cake is made by the Master Cook and shared with Twenty-Four children. The current Master is not particularly skilled in his job and often relies on his apprentice. However, he ignores it when the apprentice tells him not to add the Faery Star to the cake, which ends being eaten by young Smith.

On Smith’s tenth birthday, the star begins to glow on his forehead, and he has many adventures, including into Faery itself.

As you can probably tell, Smith of Wootton Major is not an epic quest narrative filled with battles and doom (as you may expect if you have only read The Lord of The Rings). Instead, this is a more charming and quiet work of his, resembling more closely Leaf by Niggle or The Adventures of Tom Bombadil.

I don’t want you to get the impression from this it is boring or frivolous. If the Middle Earth novels are like your eighth Birthday Party with all your best friends, this is like snuggling up by a roaring fire with a mug of cocoa and a wonderful book. Different but can be equally enjoyable.

As anyone at all familiar with him will tell you, Tolkien is an absolute master of language and can use it multiple ways to create whatever effect is needed. Here he creates an effortless amiability about the whole thing, introducing wit and joy without seeming forced or conceited. The story is just a marvelous experience.

Apparently, this story came from another project, specifically as an introduction for a new version of George MacDonald’s The Golden Key. He wanted to explain about Faery using this as a kind of metaphor; however, this ended up being expanded into a story in its own right, one I am very glad to have.

A strong Four Stars

by Olav Rockne

It seems odd that Dodie Smith’s latest novel The Starlight Barking has flown under the radar.

It is written by a great novelist who is beloved by mainstream literary publications, and whose play Dear Octopus is currently a hit in the West End. It has been praised by luminaries such as Christopher Isherwood. Moreover, it is the sequel to a beloved children’s classic, the movie version of which was the first movie ever to earn more than $100 million in the cinemas.

And yet, it is also a very odd illustrated novel. Though I find much to recommend in the work, I can understand why it seems not to have grabbed the public imagination as much as the work to which it is a sequel, The Hundred and One Dalmatians.

Picking up shortly after the first book, The Starlight Barking finds the protagonist Dalmatians Pongo and Missis living in Suffolk. One night, all living beings other than dogs fall into a deep magical sleep. The dogs also discover that they can fly, communicate across long distances, and operate machines.

Each dog takes on the jobs of their owners. Having been adopted by the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Cadpig (the runt of the litter from the first book) is therefore now in charge of the country. She summons her family to London to help.

A subsequent scene in which the United Kingdom Cabinet goes to the dogs is a highlight of the book. Followers of British politics will note the well-drawn satire of Secretary of State George Brown depicted as a clumsy but cosmopolitan Boxer, and Minister of Transport Barbara Castle depicted as fussy and officious poodle. (Is the refusal of James Callaghan to devalue the Pound the reason that his dog is shown as being less mathematically inclined than the other dogs?)

Back in Suffolk, Cruella de Vil’s Persian cat — who helped the dogs escape in the first novel — turns out to be unaffected by the sleeping illness as she was named an “honourary dog.” The cat suggests that Cruella must be behind the plague of sleep, and therefore must be killed. But when the dogs find Cruella, she is asleep like the rest of humanity. So they spare her.

An alien, Dog Star Sirius, appears at the top of Nelson’s column in Trafalgar Square. He admits that he is behind the sleep, and that he has come to Earth to save dogs from an impending cataclysmic nuclear war.

Sirius invites all dogs everywhere to join him in the sky, and gives them a day to decide. Pongo is given the final choice. I won’t spoil the ending, but let me be completely up-front here: it doesn’t get less weird.

This is a flawed and chaotic short novel. But it is that chaos of a childhood flight of fancy; unbounded by expectation, and brimming with whimsy. Dodie Smith’s writing alternates between compelling action writing, and something poetic and magical. Her evident affection for dogs in general leads her to make them very lovable characters.

Given that the only animated movie that Disney has released since 101 Dalmatians was a critical and commercial flop (The Sword In The Stone earned just $20M), they may try to film this sequel. If and when they decide to do so, I hope they have the ambition and the audacity to stay true to this novel.

I would wager that if there were a Hugo Award category to celebrate works geared for younger readers, The Starlight Barking would be a strong contender for that shortlist.

![[November 18, 1967] Escape Velocity (November Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/671120covers-672x372.jpg)

![[October 18, 1967] We Are The Martians: Quatermass and the Pit, Bonnie and Clyde, The Day the Fish Came Out and The Snake Pit and the Pendulum](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671018posters-672x372.jpg)

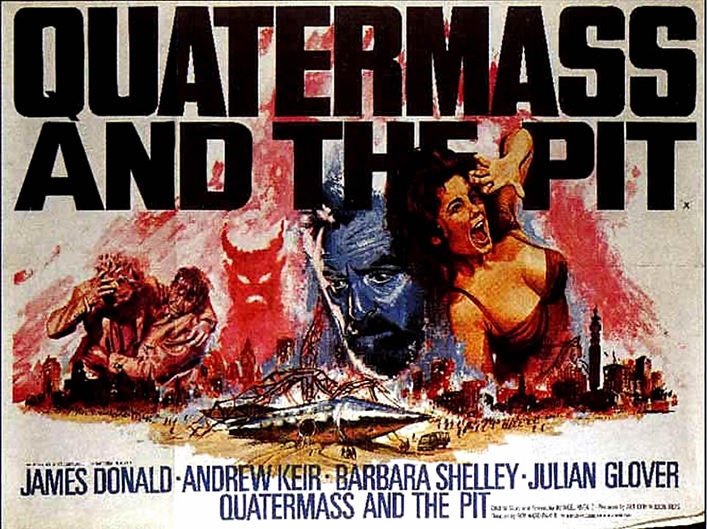

Likeable: Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Barbara Shelley as Miss Judd

Likeable: Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Barbara Shelley as Miss Judd Colonel Breen, representing humanity's negative side.

Colonel Breen, representing humanity's negative side. Hammer's take on the Martians.

Hammer's take on the Martians.

![[October 10, 1967] Jack the Ripper and Company (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>,Part One)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1967_Dangerous-Visions-hc-2-672x372.jpg)

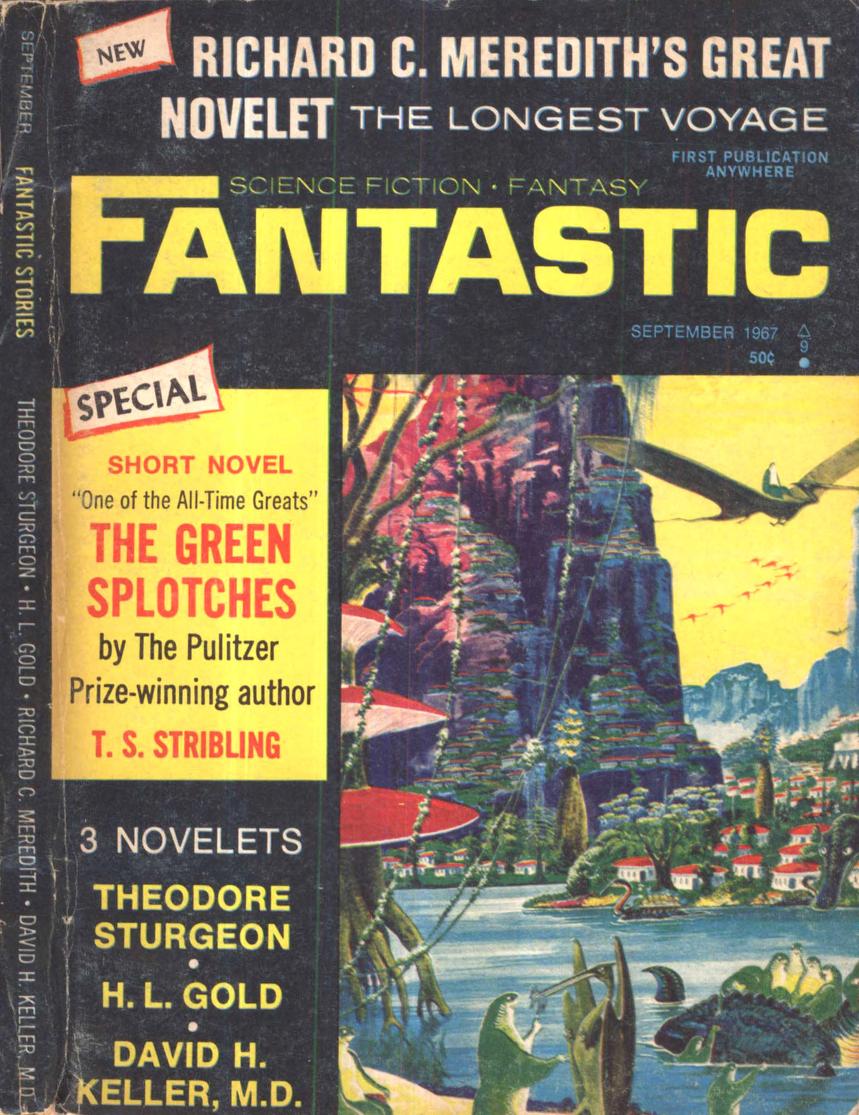

![[October 8, 1967] Things Fall Apart (November 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Fantastic_v17n02_1967-11_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[September 12, 1967] Heavens Above! (<i>The Fifteenth Pelican</i> and <i>The Flying Nun</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/sddefault-2-619x372.jpg)

![[September 10, 1967] Women's liberation! (September 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/670910featured-672x372.jpg)

![[August 12, 1967] Planetary Adventures (August 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670812covers-672x372.jpg)

![[August 8, 1967] Distant Signals (September 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Fantastic_v17n01_1967-09_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[June 16, 1967] What's Going On Here? (June 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670616covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1967] Music To Read By (July 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fantastic_196707-2-1.jpg)