By Mx Kris Vyas-Myall

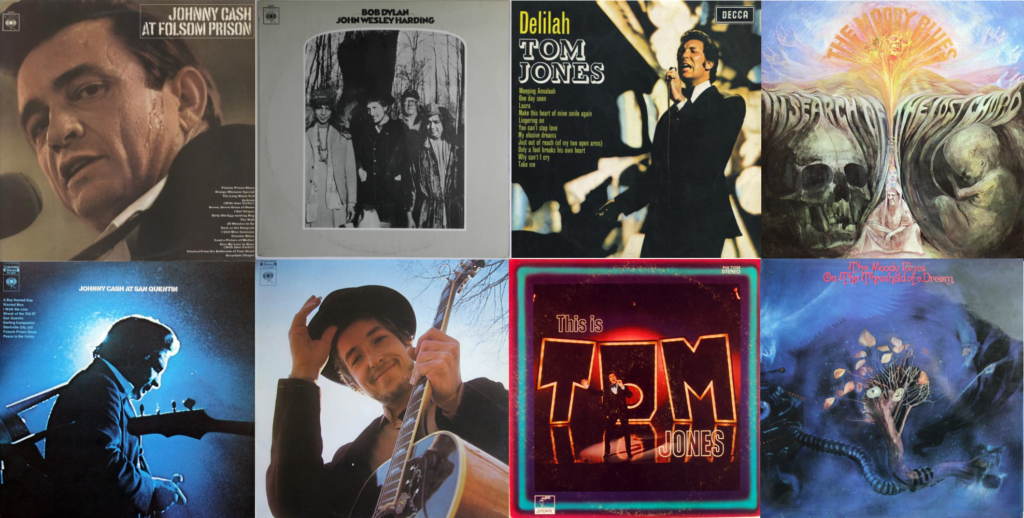

Among musicians right now, there seems to be a split around whether to look towards an experimental future or an idealized past for their inspiration.

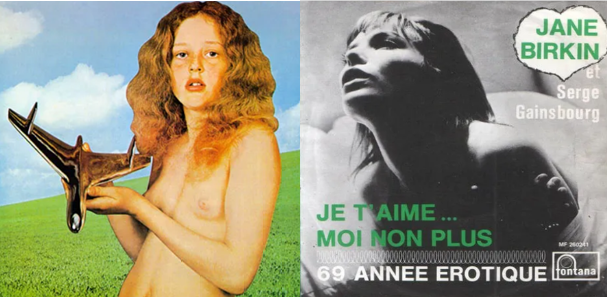

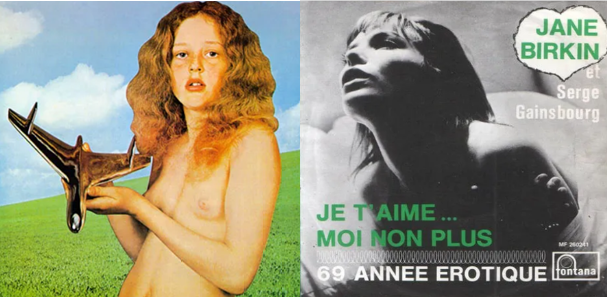

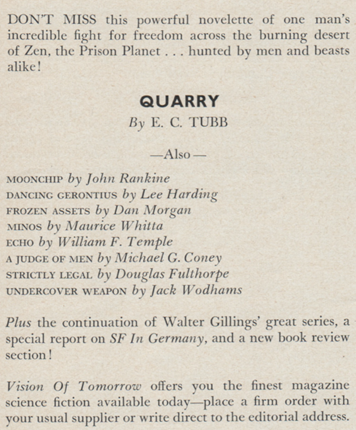

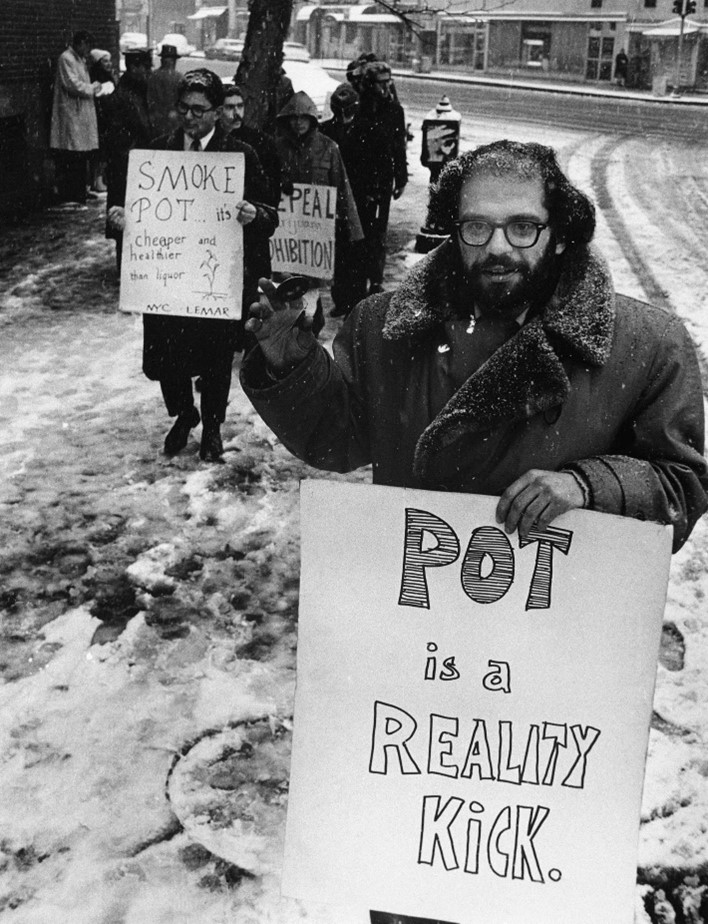

Both in pop music and SF, nudity and sex remain sources of controversy.

The most explicit examples of Futurism come from two recent singles, Zager and Evans’ In the Year 2525 and David Bowie’s Space Oddity. But there is also the debut album from King Crimson, featuring the song 21st Century Schizoid Man, The Moody Blues’ space inspired LP, and Pink Floyd performed a new piece recently in honour of the Moon Landing. In addition, the music industry is pushing what is acceptable sexually whether that be in artwork, such as the Blind Faith cover above, or interesting choices of sounds on pop songs.

Did the Kinks have a point about preserving village greens?

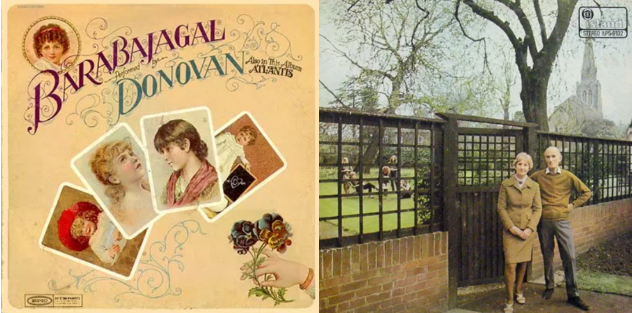

On the other hand, at this time last month 4 of the top 5 singles were all country influenced songs, from Bobbie Gentry, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan. Now, there has always been some country influence in the charts (as shown by Jim Reeves having 7 posthumous top 20 singles and counting) but it is certainly reaching a new level when the Beach Boys and Rolling Stones are both trying it out. In addition, folk is also growing, often with a nostalgic edge, in such songs as Fairport Convention’s Who Knows Where the Time Goes or Donovan’s Atlantis.

These differences can also be seen in SF and, perhaps, there is no clearer division than that which can be observed between the two publications I am reviewing today.

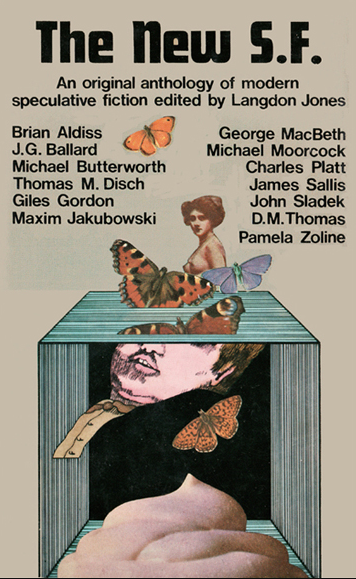

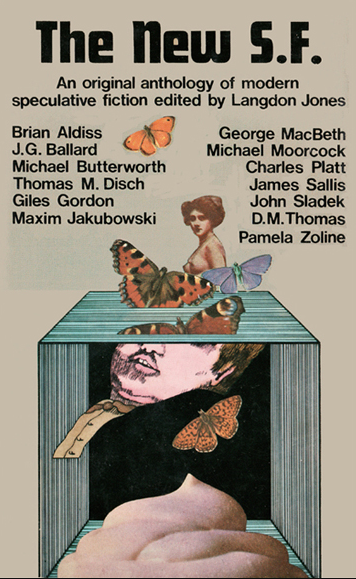

The New S.F., ed. by Langdon Jones

Cover by Colin Mier

An introduction by Michael Moorcock

Who else would you choose but Moorcock to introduce this selection of New Wave authors? Here he talks about how the “new SF writers” or “New Worlds group” have moved beyond spaceships and monsters to do more person-centric poetic pieces.

Fourteen Stations on the Northern Line by Giles Gordon

Fourteen different men observe an unnamed woman to different degrees of lechery as she walks up a hill. She fails to notice them as she has other things on her mind.

If it was not in this collection, it would probably not be considered SF, more akin to a Joyce than a Gernsback, only approaching the latter with the surrealism of the mind.

Moorcock’s introduction notes this as an example of a “compacted novel”, one that could be extended to a traditional novel but that would blunt the impact significantly. I cannot determine if I wanted this to be longer, shorter or reworked, but something is amiss. The metaphor, though obvious, is a good one (what passenger on a train pays attention to the small commuter stations?) and the difference in the inner lives of the observer and observed make a solid basis. But it left me wanting something better from it.

Three Stars

The Peking Junction by Michael Moorcock

A Jerry Cornelius story from his creator. In this episode, Europe has been devastated by American bombs (of course Europe still supports their allies in this action) and our dandified spy goes to China to deal with a downed American plane. His mission is complicated by the fact that he falls in love with one of the Chinese generals.

One interesting element here is Moorcock explicitly calls out the connection between Cornelius and his other tales:

Having been Elric, Asquiol, Minos, Aquilinus, Clovis Marca, now and forever he was Jerry Cornelius of the noble price, proud prince of ruins, boss of the circuits. Faustaff, Muldoon, the eternal champion…

There was always a suggestion of this previously, and The Blood Red Game (Science Fiction Adventures, 1963) and A Cure for Cancer both feature multiple universes, but I believe this is the first time we get it confirmed that this is not simply a case of repeated motifs.

Looking at it in this manner, we see the biting contemporary satire evolving into a more epic struggle and Moorcock’s other heroes as more than just throwaway fantasy figures. Rather there is a degree of tragedy in them having to deal with these various forces of order and chaos, making horrific choices for, what they hope, is the greater good (which rarely ends well).

A High Four Stars

Fast Car Wash by George MacBeth

A car gets cleaned… that is the entire story.

Moorcock calls this a readymade poem. I am assuming forthcoming are also a transcription of microwave instructions and George MacBeth’s shopping list.

One star

The Anxiety in the Eyes of the Cricket by James Sallis

Another Jerry Cornelius story, who is seemingly becoming to the New Wave what the Cthulhu tales have become to SF horror. This vignette apparently takes place shortly after the end of The Peking Junction (although Moorcock indicates this is better read as an alternative version) as JC returns to England a broken man. He stays in the house of his friend Michael, a man who predicted the apocalyptic future. They spend their time drinking and having sex between watching devastation from their window and discussing the nature of guilt.

A much quieter tale and more introspective than the other Cornelius tales with a good dose of narrative experimentation (if Michael is not surnamed Moorcock, I will eat my hat) added in. It is also incredibly bleak, with cities burning, Britain used as America’s crematorium, and Cornelius a broken man now simply looking for his missing family. But it is all the more powerful for it.

Five Stars

The New Science Fiction: A Conversation between J. G. Ballard & George MacBeth

This is the transcription of part of a discussion on BBC Radio 3 (formerly the Third Programme) last year titled The New Surrealism. In this extract, J. G. Ballard explains why he moved away from linear storytelling.

I missed this on its broadcast and I am very pleased it was reproduced here. Ballard manages to explain eloquently what he is trying to achieve in his stories and it has given me an increased appreciation for his work. Two sections I want to call out here as particularly incisive:

…one has many layers, many levels of experience going on at the same time. On one level might be the world of public events, Cape Kennedy, Vietnam, political life, on another level the immediate personal environment, the rooms we occupy, the postures we assume. On a third level, the inner world of the mind. All these levels are, as far as I can see them, equally fictional, and it is where these levels interact that one gets the only kind of inner reality that in fact exists nowadays.

…Burroughs’s narrative techniques… [are] an immediately recognisable reflection of the way life is actually experienced, that we live in quantified non-linear terms – we switch on television sets, switch them off half an hour later, speak on the telephone, read magazines, dream, and so forth. We don’t live our lives in linear terms in the sense that Victorians did.

Recommended for fans and confused readers alike.

Five Stars

So Far from Prague by Brian W. Aldiss

Another of Aldiss’ tales of Europeans in India. This time Slansky, a Czech filmmaker, is staying in a Das’ hotel outside Delhi when he hears of the Soviet invasion, He wants to get back home to help resist the attack, Das thinks they should be concentrating on their joint film project on the nature of time. Things get even more complicated when Slansky discovers there is a Russian guest in the room below his.

Interestingly, this manages a similar feel to Sallis’ piece even though it is contemporary rather than apocalyptic and could only be considered SFnal in the broadest sense. Here it is an exploration of the age-old argument of whether art can or should be apolitical, with this sense of gloom and despair. An important reminder that worlds are being blown up outside our window, not just in our magazines.

Four Stars

Direction by Charles Platt

An unnamed man has an argument at home. In response he gets drunk in a pub and then wanders around London in an inebriated haze.

Another piece where I am not sure the point of it, nor what it is doing in an SF anthology. There are some interesting writing techniques but that is all I can see to recommend it.

A low two stars

Postatomic by Michael Butterworth

We are told of four impossible beings, who may or may not be the same character across different time periods.

Not sure what its purpose is but it is certainly evocative.

Three Stars

For Thomas Tompion by Michael Moorcock

Moorcock completes his trilogy of entries with a four-line poem, addressed to the father of English clock-making.

Simple but well done for what it is.

Three stars

A Science Fiction Story for Joni Mitchell by Maxim Jakubowski

A science fiction writer has grown dissatisfied with the genre; instead he wants to write neo-psychedelic pop songs and tales of drug journeys. However, he has a deadline to hit, and the adventures of Coit Kid vs. the Subliminal Police don’t write themselves. Anyway, there is no chance of his other ideas intruding on a good old-fashioned science fiction story, is there?

A hilarious take on writing, modern pop music and science fiction cliches. It is done in a series of cut up pieces but logical rather than disparate. The whole exercise is delicious and I am going to be remembering many of the lines for some time.

Five Stars

The Communicants by John Sladek

This novella is a fragmented narrative, telling of a disparate set of people who work at Drum Inc., a technology company which provides a wide variety of services over phone lines and dreams of superseding Bell as the national monopoly.

Members of this organisation include Marilyn, who keeps getting mysterious calls that simply say “Marilyn, he loves you”, Sam Kravon, who is being driven mad by his job in Estimates, Phil Wang, the Art Director who is sure people are questioning his loyalty to the US, Ray, a cripple who is being constantly shuffled between departments, and David, who believes reality is refrangible.

At the same time, there are hints of experiments going on within the company that are of interest to the CIA.

Partially this is an extension of his multiple-choice form tales from New Worlds, with these regularly interrupting the text. And partially this is an experiment of split narratives, with the narrative like a butterfly flitting between different stories with such regularity that I wondered if I could use a flow chart.

Whilst it is an interesting experiment, it goes on for far too long (at almost 70 pages, far longer than anything else in this collection) and the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

Three Stars

Seeking a Suitable Donor by D. M. Thomas

An organ donor before their surgery contemplates his journey to this point.

The strange alignment of the text doesn’t add much to this tale of familiar themes but a perfectly reasonable example.

Three Stars

The Holland of the Mind by Pamela Zoline

Graham, Jessica and their child Rachel take a holiday from the US to Amsterdam in 1963. However, visiting the Venice of the North is not going to help them outrun their problems.

This is a tricky one to review. On the one hand it is beautifully written but shocking look at depression and the breakdown of a marriage, counterpointing the history of the Netherlands with their personal situation.

On the other, it is barely SFnal. There is one moment towards the end which could be taken as such. But it could also be taken as metaphorical and\or natural phenomena. As such I was partially disappointed. It reminded me somewhat of Morris’ travelogue Venice.

However, I adore Morris’ writing. As such I am happy to give it the benefit of the doubt and judge it as a piece of literary short fiction. On those grounds it is brilliant.

Five Stars

Quincunx by Thomas M. Disch

As the name suggests, this is made up of five vignettes:

• Chrysanthemums: Mr. Candolle ponders the meaning of chrysanthemums in hospital rooms

• Representation: The narrator speaks of his lost love Judith

• The Death of Lurleen Wallace: A circular tale of princes, presidential campaigns and books

• Mate: A letter from former lovers which also deals with a correspondence chess match

• The Assumption: Miss Lockesly teaches her class about death

I am not sure though what shape we are meant to form. To some extent they are all about endings in different ways but no consensus is reached nor are they particularly profound.

Two Stars

Thus ends this experiment of a book, one which I have rated all over the place. To change a famous quote, there is a thin line between genius and drivel. This anthology erases it.

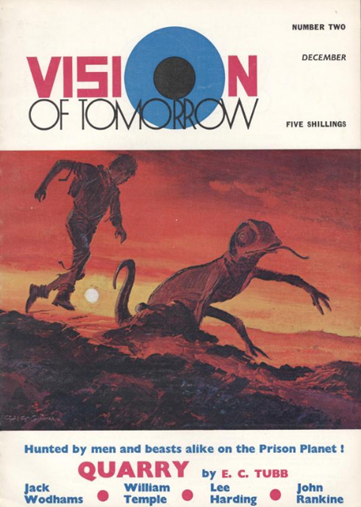

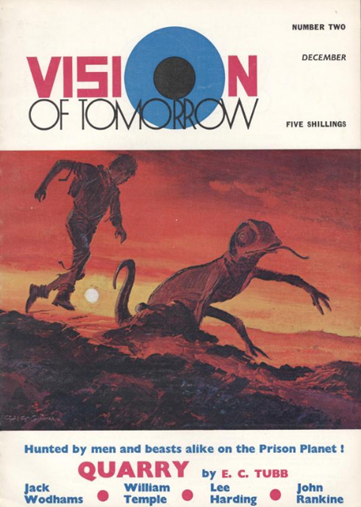

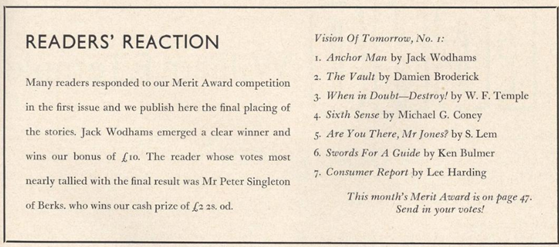

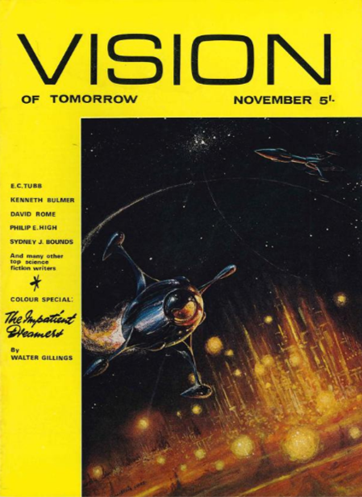

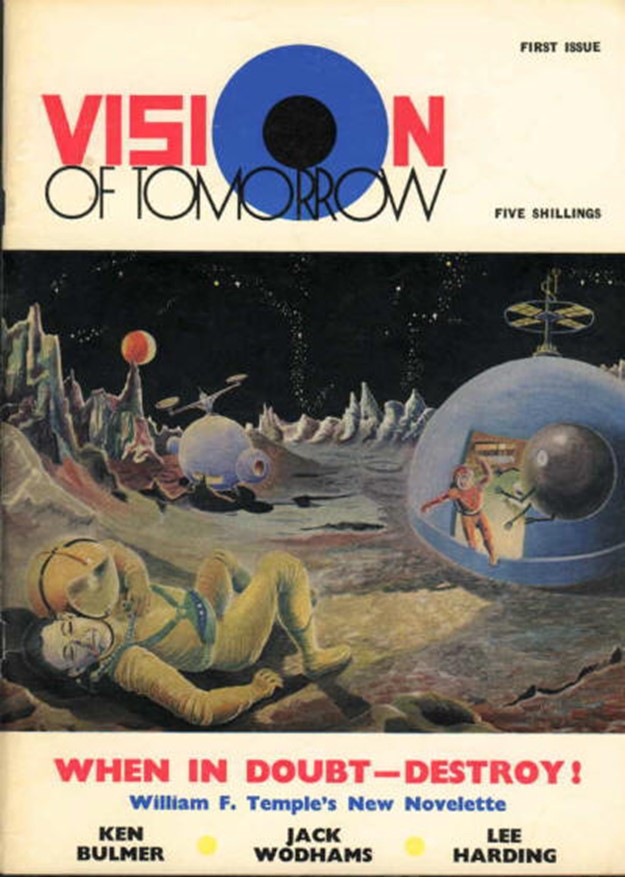

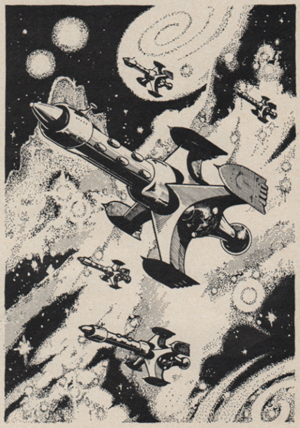

Vision of Tomorrow #2

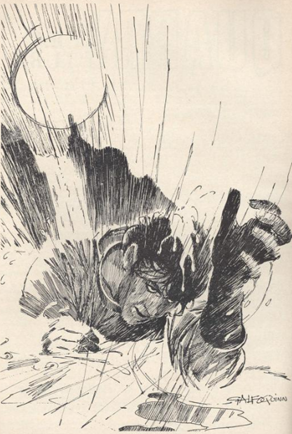

Cover Illustration: Gerard Alfo Quinn

Issue #2 has finally arrived. No explanation is given for the delay other than “circumstances beyond our control”. Whatever the reason, we shall now dive into the contents:

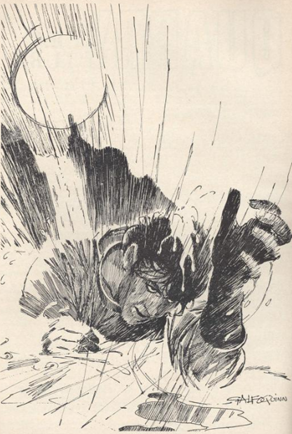

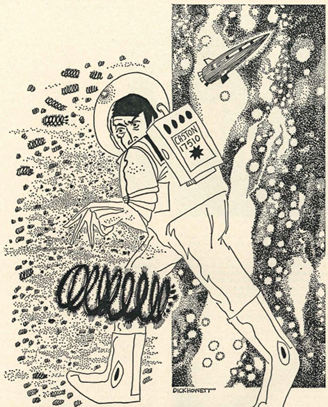

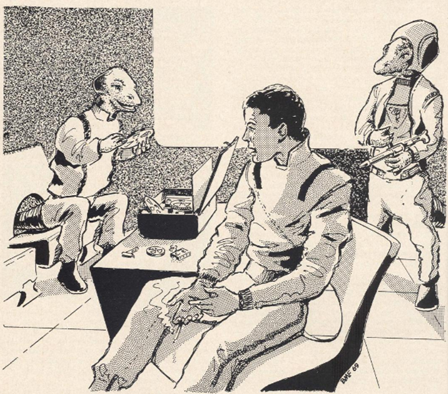

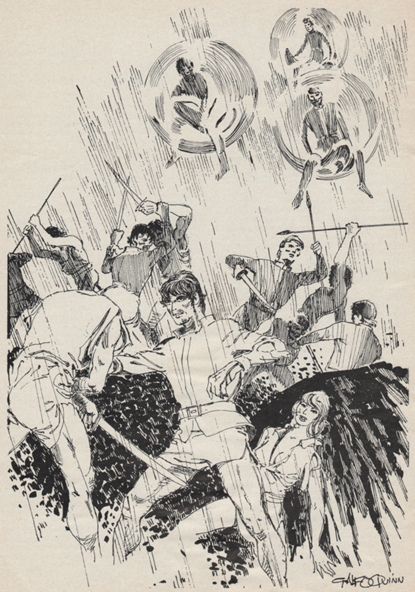

Quarry by E. C. Tubb

Illustrated by Gerard Alfo Quinn

Quelto Daruti is a prisoner of the Federation. he decides to make use of an obscure law. The Quarry-Hunt. He is to be hunted across the harsh landscape of Zen to sanctuary. If he can make it alive, he will be pardoned, but the only person who ever managed it before died of their wounds soon afterwards.

Durati however has two advantages the authorities do not know about. Firstly, he is a telepath. Secondly, the Terran league are very interested in his survival

Yes, it is yet another spin on The Most Dangerous Game, but a pretty good one. Stylistically it can be heavy at times, but this is made up for when it is action packed.

Just sneaks in at four stars.

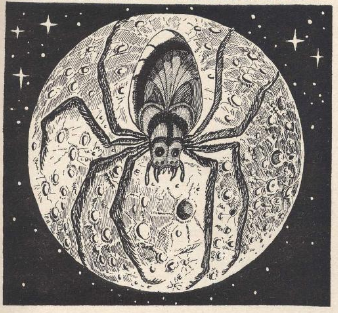

Strictly Legal by Douglas Fulthorpe

Illustrated by James

The intelligent spider-creatures of Proxima Centauri claim ownership of Earth’s Moon, on the grounds that it detached from one of their planets when it was molten. At first everyone assumes this is a joke. However, it turns out they are in deadly earnest, and the legal implications of the case will have devastating consequences.

This is a slippery slope argument delivered with all the subtlety of a brick through a window. The style is readable enough, but it requires so many “what-ifs” to make the idea work, I am not surprised everyone inside this piece of fiction assumes it is all a joke.

Two Stars

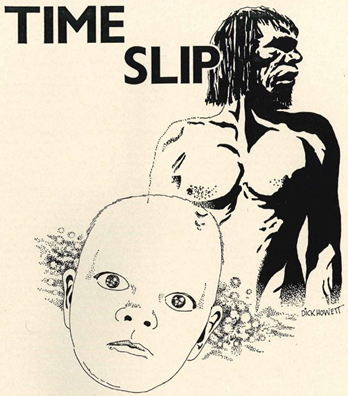

Moonchip by John Rankine

Millenia ago a small piece of metal fell to Earth. It has now been mined and ended up part of a car, one that is involved in a strangely high number of fatal accidents. But that is just coincidence, right?

I found this to be a dull and violent tale with little purpose. Maybe if you enjoy hoary old horror stories or car-based fiction it will appeal to you, but not to me.

One Star

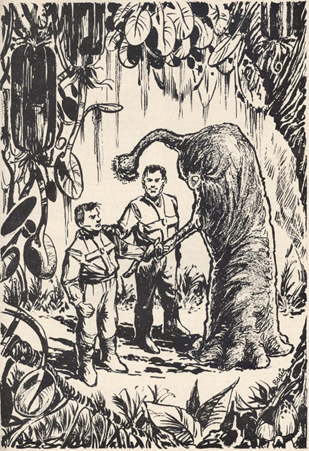

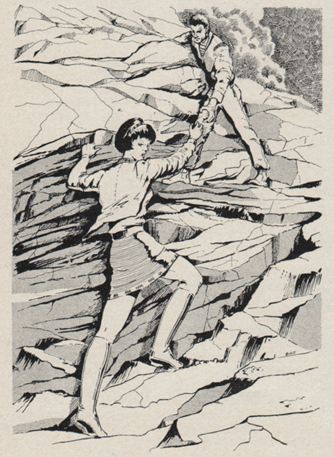

A Judge of Men by Michael G. Coney

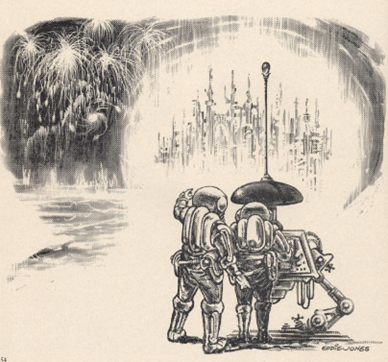

Illustrated by Eddie Jones

Scott travels with the trader Bancroft to the planet Karumba, the only source of Shroom (a kind of puff ball that can be woven) in the galaxy. The Shroom harvest is lessening as the planet gets colder and Karumbans may face extinction. However, having seen how humans treat animals in zoos, they refuse to allow any scientific help from humanity. Bancroft is willing to respect the Kamburans' wishes, the young ambitious Scott, however, is determined to solve the mysteries of this world, no matter what anyone else may think.

This did not go in the direction I expected. This started out seeming like it was merely going to be an experiment in xenobiology and the effects of planetary tilt but it went into much deeper territory around what it means to be a person, respect for native belief systems and the responsibility of ethical science.

My only complaint is it was too short to address all of the areas it touched on properly. I would love to see it expanded into one-half of an Ace Double.

A high four stars

Frozen Assets by Dan Morgan

Larry is a used air-car salesman who, with his fiancée Olivia is determined to find a way to get rich quick according to their realist philosophy. The first scheme involves being married to a wealthy divorcee but it turns out the pre-nuptial agreement states that Olivia won’t get any money from accidental death until after five years.

Larry then discovers there is a cure for cirrhosis of the liver, a condition his rich uncle Frank was cryogenically frozen with. He hopes to revive Frank and take control of his estate, however Frank is not quite as witless as Larry supposes.

This is the kind of story I dislike. It requires the setting up of a series of silly rules people follow, explaining them as they go along. In addition, it wends all over the place, barely sticking in one place for more than a moment.

One star

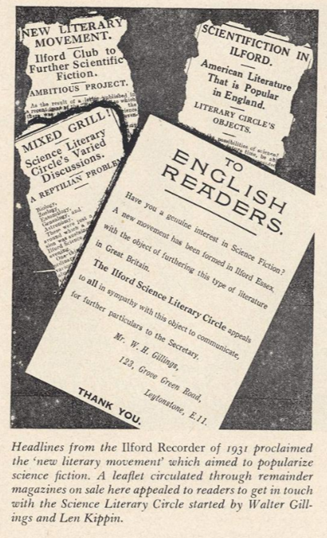

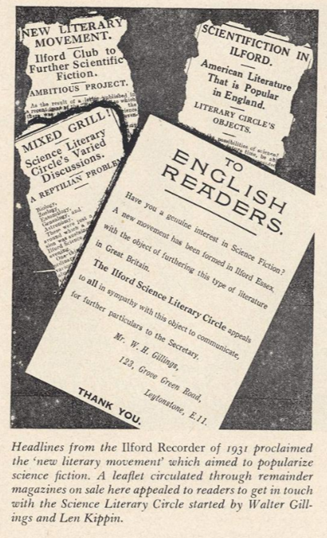

The Impatient Dreamers 2: Aims and Objects by Walter Gillings

Filling in the gap between installments 1 and 3, we learn of Gillings' efforts to show that there is a strong enough market for science fiction in Britain to support a magazine.

This series continues to be excellent and contains a lot of fascinating details. Such as that Britain at this time didn’t have specialist fiction magazines at all and that Len Kippin just would hand out leaflets wherever he saw SF on sale.

Five Stars

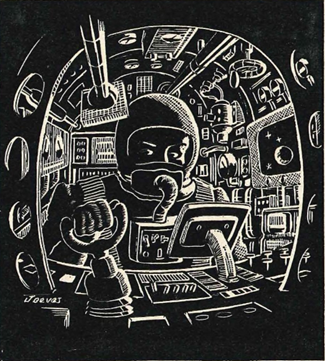

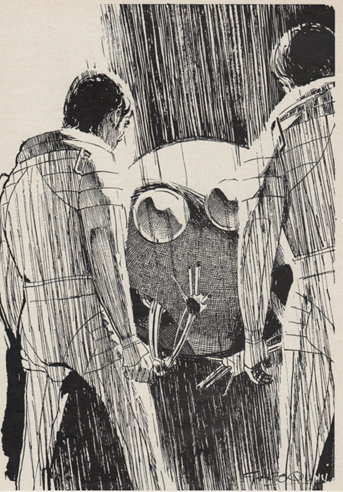

Echo by William F. Temple

Illustrated by B. M. Finch

The Saurian Venusians have taken over the body of Richard Gaunt by use of a temporary echo of the personality of Narvel. They intend to steal the secrets of Organic Materials Inc., however, it turns out that being a human is harder than it seems.

I actually covered this last year in Famous, and I was planning to just reprint my review from there. However, curiosity got the better of me and I decided to look for any changes. I was taken aback that it was almost entirely rewritten. The plot remains identical but the prose is almost a complete overhaul. To compare one of the more similar sections:

Famous version:

Being a mammal, without previous experience, was to me a series of surprises, mostly unpleasant.

Gaunt, I knew, had the social habit of drinking whiskey. I first drank whiskey on the Pacific with a couple of engineers from Minneapolis.

After a while, I remarked with some concern. “Darn, it, the grav-motors are failing.”

This sometimes happened on space trips, and until they were repaired everyone had to endure free fall. I’d felt the beginning of free fall coming on; at least, I felt I was beginning to float. And I said so.

The two men looked at me strangely, then at each other.

“One whiskey on the rocks and he’s floating,” laughed one.

And the Vision version:

I became a Tyro mammal among experienced mammals.

My deficiencies first began to show on the spaceship to Earth. On the passenger list I was Richard Gaunt. I was Gaunt, physically. I did my best to act like him personally.

I knew he had this social habit of drinking whisky. I gave it a whirl at the bar with an engineer from Minneapolis.

After two whiskies, I remarked, ‘What’s gone wrong with the grav-motors?’

My companion looked at me strangely.

‘They seem okay to me. Sure I’s not the whisky hitting you? This special space brew is potent, you know, if you’re not used to it.’

Now, the scene being depicted has the same purpose: Narvel giving an example of not being used to certain human situations with impersonating Gaunt by his lack of familiarity with Whisky causing him to think there is an issue with the grav-motors. But the feel is completely changed. The prior version is concentrating on feelings and giving it a more comedic sense. The new version is more cerebral and philosophical about the nature of identity.

I still have a number of problems with the text but the changes make it clearer to me what he is trying to do. As such it jumps up a little bit in my ratings.

A low three stars

Undercover Weapon by Jack Wodhams

Illustrated by James

The Fiberphut fabric disintegrator was developed as a means of removing bandages without damaging the skin underneath. When the army look to test its possible military applications, Lt. Cladwell makes his own duplicate model at home. He and his brother-in-law are determined to make a fortune from this device…along with many amorous encounters along the way.

This is the kind of unfunny sex comedy that seem to be growing in popularity at the cinema these days. I don’t like it there and I don’t like it here. I am a little surprised to see this included given last month’s stated “no pornography” policy, but I guess as nothing is described it is considered “good clean fun” by Harbottle. I, on the other hand, find it lecherous and dull.

One Star

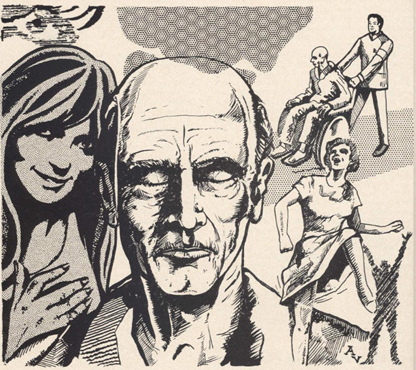

Dancing Gerontius by Lee Harding

Illustrated by A. Vince

The elderly on welfare are generally kept in a dream-like state in specialist facilities. However, annually they participate in Year Day, where a combination of drugs and advanced machinery allow them to participate in a period of bacchanalian hedonism. We follow Berensen’s experiences as he is crowned King for the day.

An evocative piece that did not go in the direction I expected it to. Quite haunting by the end.

Four Stars

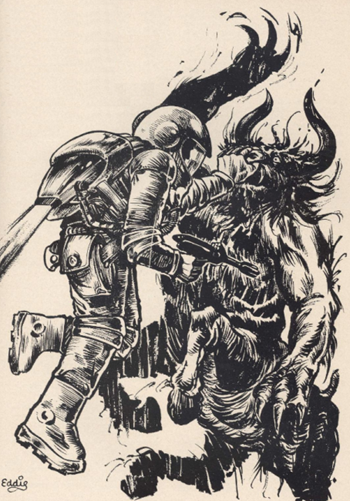

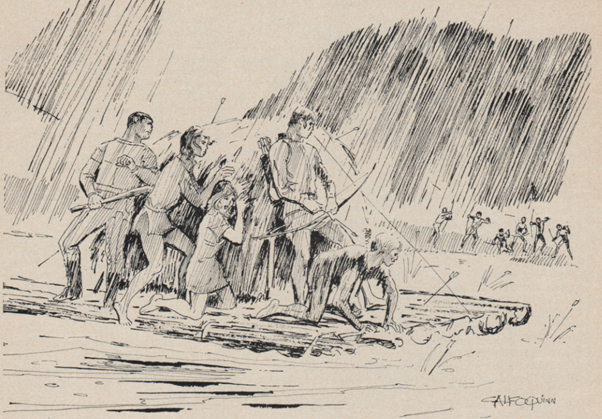

Minos by Maurice Whitta

Illustrated by Eddie Jones

The final piece is by a new writer to me. The colony-ship Launcelot crash lands on Amor VII, killing almost ¾ of the occupants, including all the women. Another ship primarily composed of women also makes landfall, but contact is lost. From the Guinevere there start emerging minotaur like creatures that attack the men of Launcelot, what could have happened?

This whole piece is kind of a muddle, smelling to me of new author problems. The concepts are good and the point an interesting one. At the same time the action sequences are well written. The problem is structural. For such a small piece too much time is spent in irrelevant sections and the more poignant parts are rushed.

It is not bad though and I hope that Mr. Whitta can sort the issues out in the future.

A low Three Stars

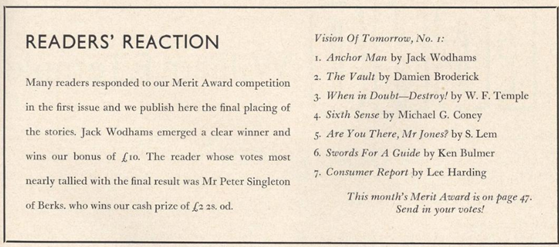

Story rankings from issue 1, my main surprise is seeing the fascinating Lem below the woeful Coney, but each to their own.

Fantasy Review

Illustrated by Philip Harbottle

Ken Slater reviews Timepiece by Brian N. Ball (which he did not enjoy) and Harry Harrison’s Deathworld 3 (which he did). We then have a new reviewer, Kathryn Buckley, covering Stand on Zanzibar in a highly complementary manner. Perhaps trying to balance coverage of the New Wave along with the Good Old Stuff?

Best of Both Worlds?

Additional illustration by Eddie Jones

In both my SF and my music, I am generally drawn towards the future facing experimental works, preferring Colosseum and Chip Delany over The Band and Edgar Rice Burroughs. But I also appreciate both have their advantages and place.

Doing a Sunday afternoon of gardening is wonderful accompanied by some Neil Young or Townes van Zandt. Just as an adventurous tale of daring-do might not be as accomplished as one of Ballard’s cut up stories, it can be a more fun and easy read.

So, whilst neither is perfect, with both the above publications showing successes and failures, I like to think that science fiction is big enough to have both our swashes buckled and our minds expanded.

![[February 6, 1970] All We Are Saying Is Give The Peace Game A Chance (<i>The Peace Game, AKA The Gladiators</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/PG10.jpg)

![[December 12, 1969] A More Liberal Society? (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #4</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/VOT3-349x372.png)

![[November 14, 1969] To Experiment or Not To Experiment, That is the Question. (<i>The New S. F.</i> & <i>Vision of Tomorrow #2</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Title-Card.png)

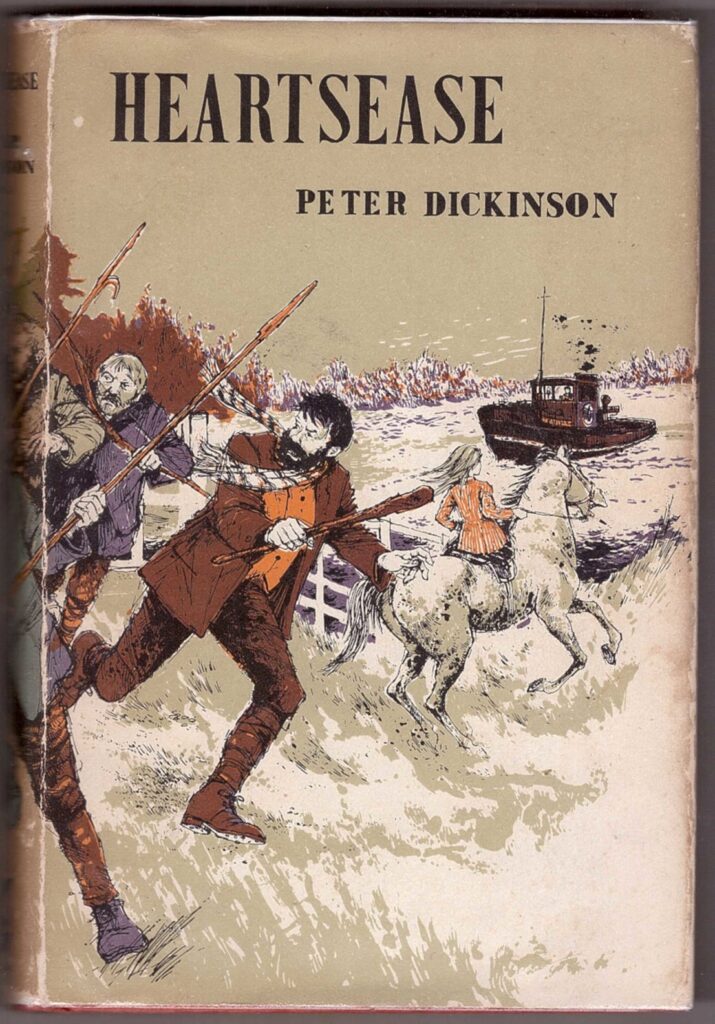

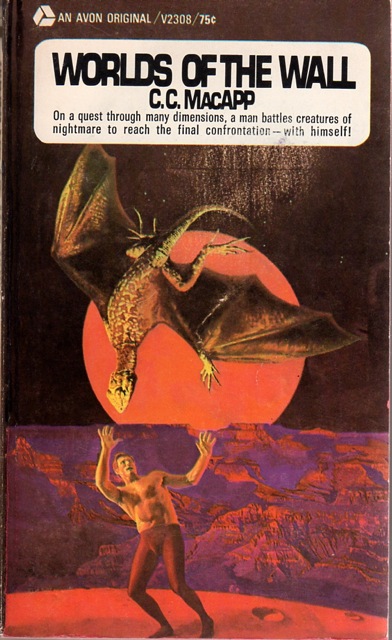

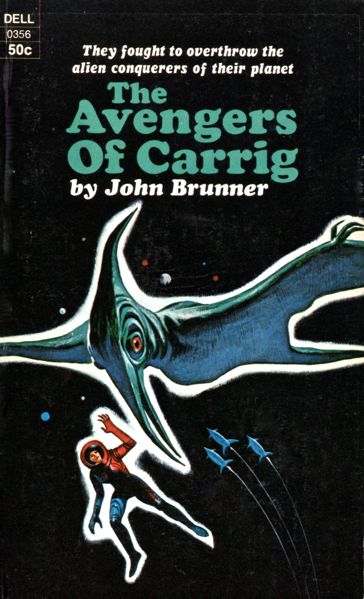

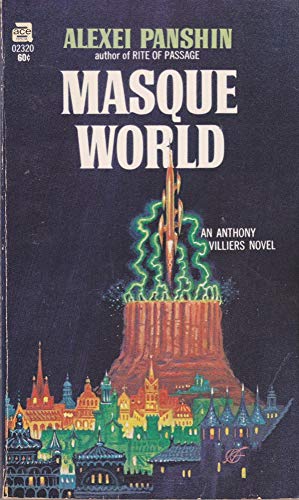

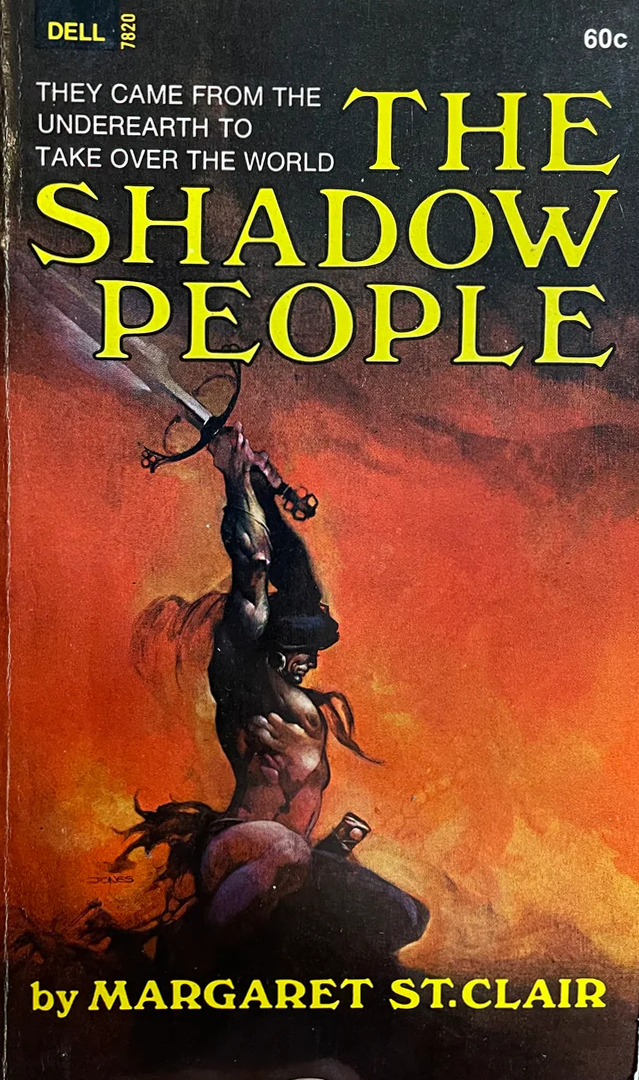

![[October 16, 1969] The March Goes On (<i>Heartsease</i>, <i>Masque World</i>, <i>The Shadow People</i>, <i>Avengers of Carrig</i>…and more!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691016covers-672x372.jpg)

![[October 6, 1969] The Rule of a Mediocracy (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #3</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Vision-2-362x372.png)

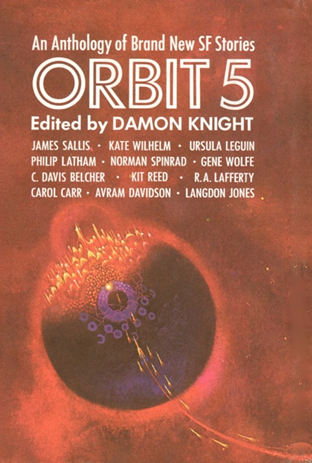

![[September 8, 1969] Another Orbit around the sun (<i>Orbit 5</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/O5-3-312x372.png)

![[August 28, 1969] Aussie-British Publishing (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #1</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/VOT2-625x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1969] Let The Sunshine In (More July Books)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690722covers-672x372.jpg)

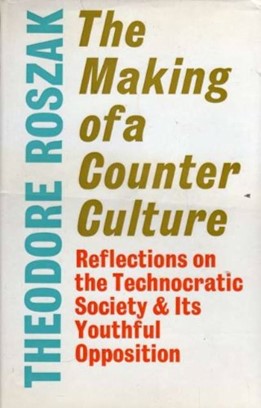

![[July 6, 1969] Everybody's talking about Revolution, Evolution… (The Making of a Counter Culture by Theodore Roszak)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CC1-261x372.jpg)

![[June 14, 1969] Boys and Girls From The North Country (The Conflict in Northern Ireland)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Troubles-5.png)