Aside from the stray short story I have to admit I had not read any of John Jakes’s novels, of which there have been many as of late—so many, in fact, that we folks at the Journey have not been able to cover every new Jakes book. Just this year alone we’ve gotten three or four Jakes novels, with at least one more already in the can as I’m writing this. So consider this a bit of “catching up,” for the both of us. Jakes started a new science-fantasy series a couple years ago with When the Star Kings Die, and this year he has put out not one, but two more entries in this series. For the sake of not overwhelming the reader, though, let’s just keep it to the first two entries… for now.

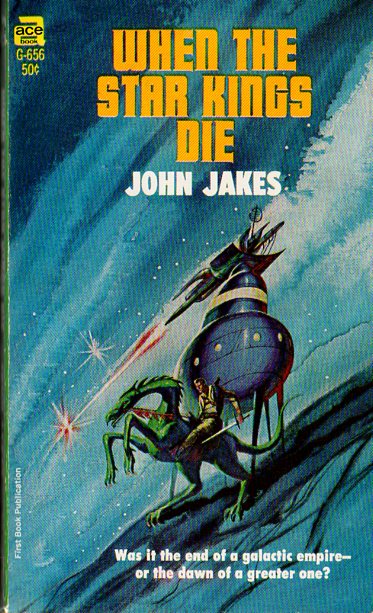

When the Star Kings Die, by John Jakes

Humanity has spread across the stars in what is called II Galaxy, with a planet-spanning league of aristocrats called the 'Lords of the Exchange' (the titular star kings) keeping things in check. The star kings are supposed to live for centuries, being near-immortal, but something has been leading these long-lived aristocrats to early deaths. Maxmillion Dragonard (a name I certainly did not pull out of a hat) is a Regulator, one of the enforcers for the star kings, who starts out imprisoned for a bout of intensely violent behavior but is soon freed on the condition that he investigates why the star kings are dying young. He soon travels to the planet Pentagon, a backwater home to little in the way of technology or civilization, but which seems to house the answer to the mystery; and there he gets involved with a group of rebels who go by the 'Heart Flag'. Dragonard’s sense of loyalty gets split between his allegiance to the star kings, personified by a mischievous spy named Kristin, whom Dragonard quickly falls in love with, and the leaders of the Heart Flag group, Jeremy and his sister Bel.

If you read certain passages out of context you might think you’re reading an adventure fantasy yarn in the Robert E. Howard mode, which Jakes is no stranger to, but overall this is much more evocative of Leigh Brackett’s planetary adventures—low on scientific plausibility but high on swashbuckling action. We have swords and daggers, but also blasters and “electroguns,” not to mention spaceships. Another thing carried over from both Howard and Brackett is this heightened sense of sexuality—or to put it less charitably, the fact that there are only two female characters of note in this novel, and both of them want to jump Dragonard’s bones. Jakes also can’t help himself when it comes to focusing on the women’s breasts, especially Kristin’s. In fairness, Dragonard is a man who has just been broken out of prison, and ultimately this is not a very serious novel. When the Star Kings Die was published in 1967, although the Journey didn’t cover it then; but if not for the publication date you might think it was printed in 1947, possibly as a “complete” novel in the likes of Startling Stories and other bygone pulps. It seems deliberately retrograde, but it’s unobtrusive so far as that goes.

This is a short novel, such that I’m actually surprised Ace didn’t bundle it with another short novel or novella. Even so, with just 160 pages Jakes is able to give us a future world, somewhat believable power dynamics among the parties, a few good villains, and a climactic battle that manages to take up a good chunk of the text. Kristin, despite being Dragonard’s main love interest, is absent for much of the novel, but to compensate his growing admiration for Jeremy and budding affection for Bel are given ample room to develop. The trio’s tenuous but promising relationship at the end of the novel is undermined, however, by the fact that when we did get a follow-up to When the Star Kings Die it was not a sequel, but instead a distant prequel.

This novel does a few things well, but not exceptionally well; and, let’s face it, we’ve been here before. It’s fine, but nothing special.

Three stars.

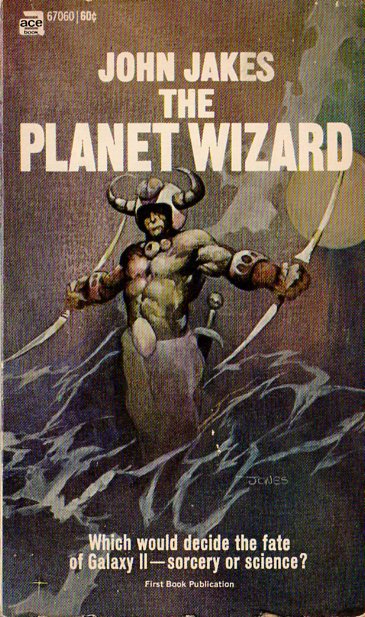

The Planet Wizard, by John Jakes

Jakes’s ode to the sword-and-spaceship adventures of yore continues with The Planet Wizard, published just this year, although given that it’s about the same length as When the Star Kings Die I’m still a bit surprised it was not released as one half of an Ace Double. The Planet Wizard has a more focused narrative, and more than its predecessor it heavily uses the fantasy elements of the pulp material it’s clearly taking cues from; but even so it feels less like a full novel (certainly now that we have behemoths like Dune and Stand on Zanzibar in the field) and more like a somewhat constipated novella. I very much enjoy novellas myself, but not so much when they look bloated and could use a laxative.

Say goodbye to all the characters from that first novel, since here we’re jumping back over a thousand years in time; conversely all the characters featured in The Planet Wizard will have been long and safely dead by the time we get to When the Star Kings Die. Some cataclysmic event has pushed civilization across planets almost back to medieval times, with the planet Pastora having only a semblance of civilized humanity, with its sister planet Lightmark faring even worse. Superstition has taken over the minds of the masses. Swords and daggers have replaced firearms. Instead of spaceships we have “skysleds.” Magus Blackclaw (another name I did not just pull out of a hat) is a middle-aged “wizard” who lives with his beautiful daughter Maya. The problem is that Magus isn’t really a wizard, for magic doesn’t really exist in this world. Whilst on the run the two cross paths with a tenacious swordsman named Robin Dragonard, who as you may guess is an ancestor of the Maxmillion Dragonard of the first novel. Magus gets captured and put on trial, as a fraud; but the High Governors, the pseudo-Christian religious leaders of Pastora, have a proposition for Magus: go to Lightmark and rediscover the fallen commercial house of Easkod, and maybe these charges will be dropped.

Not only does Magus have to deal with the “Brothers” of Easkod, a league of mutated and vicious humans who watch over Easkod City, but the job to exorcize Easkod of its “demons” quickly turns into a race. Philosopher Arko Lantzman wants his hands on Easkod as an alleged treasury of technology that got lost after the cataclysm, while William Catto, a descendant of one of Easkod’s higher-ups (so he claims), wishes to return the house to its former glory. Given that this is a prequel to When the Star Kings Die, and thus knowing the basic history of the star kings themselves, you can guess the broad trajectory of The Planet Wizard. Given also that Robin (who sadly lacks the charisma of his descendant) will contribute to a bloodline that persists over a thousand years later, it’s safe to guess as to his fate. What keeps the tension alive is that unlike some prequels, wherein we already know the fates of the cast (a kind of dramatic irony granted to the reader), we’re unsure if Magus and Maya will come out of this ordeal unscathed. While Robin is a flatter character than Maxmillion, Magus is a rather fun protagonist, being a middle-aged confidence man who nonetheless does care deeply for his daughter, and goes above and beyond to rescue her when she inevitably gets kidnapped.

In a sense The Planet Wizard complements its predecessor, and I’m not sure if Jakes intended one to be the other’s both opposite and equal. Not better, nor worse, but at least different enough to not feel like a repeat. I do recommend both—if you can find copies below the retail price.

Three stars.

by Victoria Silverwolf

Initial Response

Two rip-roaring novels of space adventure fell into my hands recently, both by authors who use two initials instead of first and middle names. (Yes, I notice trivia like that.) Let's take a look.

Escape Into Space, by E. C. Tubb

Prolific British writer Edwin Charles Tubb (E. C. to you!) has been reviewed several times by Galactic Journeyers, including your not-so-humble servant. He usually earns three stars, once in a while a bit more. Will his latest novel earn him another C or C+ on his report card?

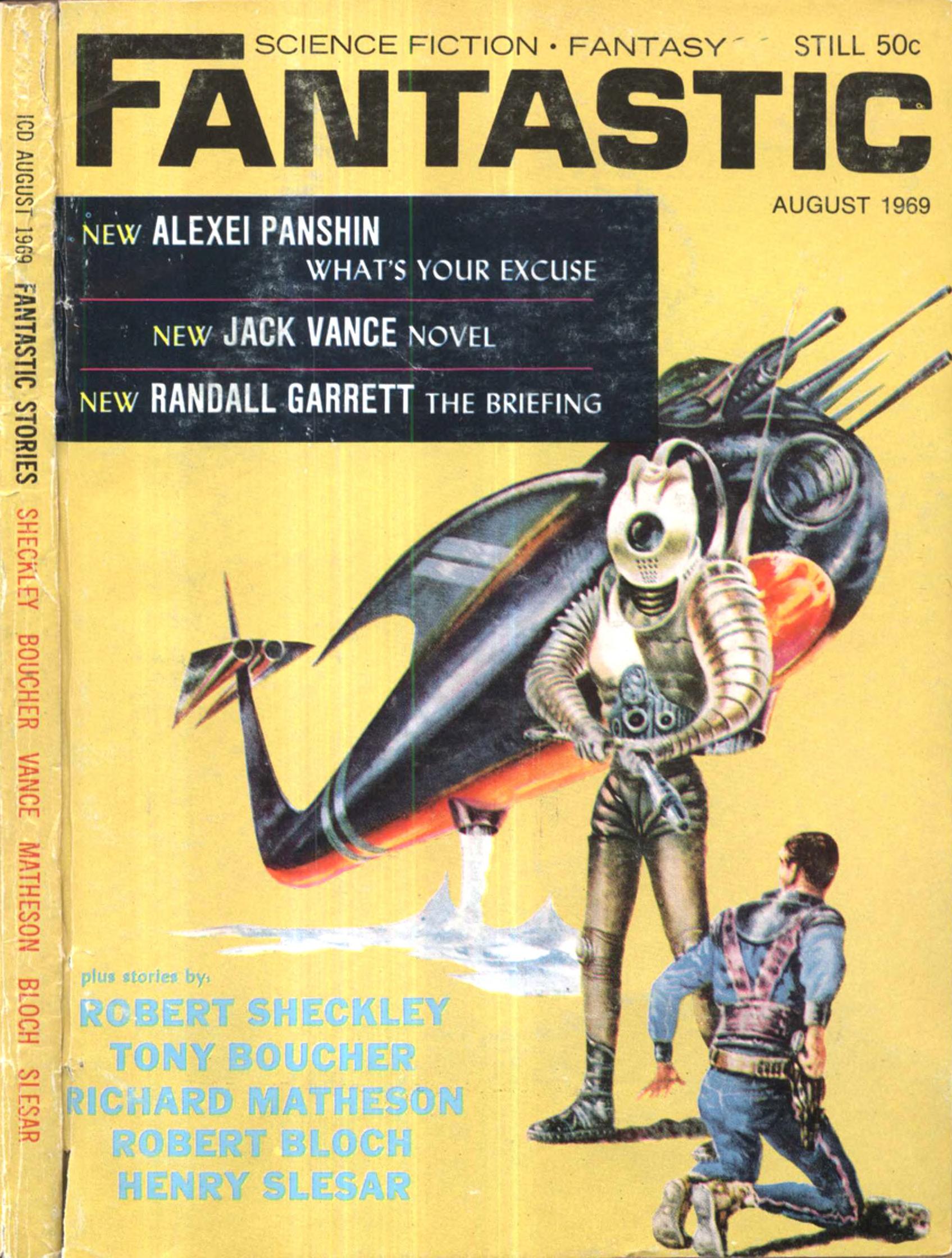

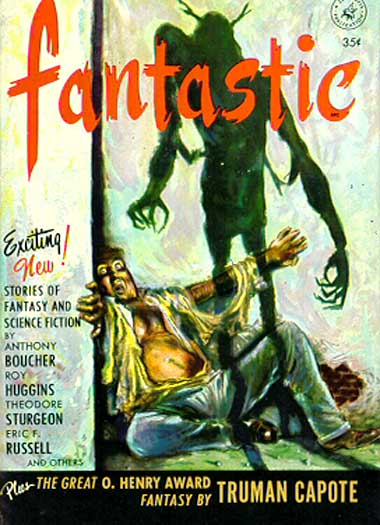

Wordiest cover I've ever seen. Pardon the lousy image.

I must have held the cameras at a bad angle.

A project to launch the first starship is under way, funded by the American government. What the boys and girls in Washington D. C. don't realize is that the folks behind the project believe that humanity is doomed to be wiped out by radioactivity. (There are hints that there have been a few limited nuclear wars, as well as a lot of atomic tests.) They plan to escape and find a world to colonize.

Meanwhile, a would-be dictator and his followers plan to stop the starship, by force if necessary. Don't worry about this subplot, because the vessel manages to leave Earth very early in the book, not without a lot of bloodshed.

(This brings up an odd thing about the book. The protagonists are just about as bloodthirsty as the antagonists. They're ready to destroy an entire community in order to launch the starship. Besides that, a lot of the folks aboard were literally kidnapped, forced to be colonists against their will.)

Pretty soon the escapees find a livable planet, which they name (with heavy irony) Eden. In addition to huge, deadly animals, the place has something in the atmosphere that ensures that any woman giving birth and her child will die.

The book has still barely started. A lot more goes on. There's an attempt at mutiny. There's the mysterious disappearance of the first probe to land on the planet, and its equally mysterious reappearance.

The author throws a lot at the reader, often at random. Some subplots don't lead anywhere. For example, we've got an attempt to activate the brain of a dead scientist in order to extract his knowledge. This is just dropped, and doesn't change anything. The whole thing reads as if it were written as quickly as possible, with a completely improvised plot.

Two stars.

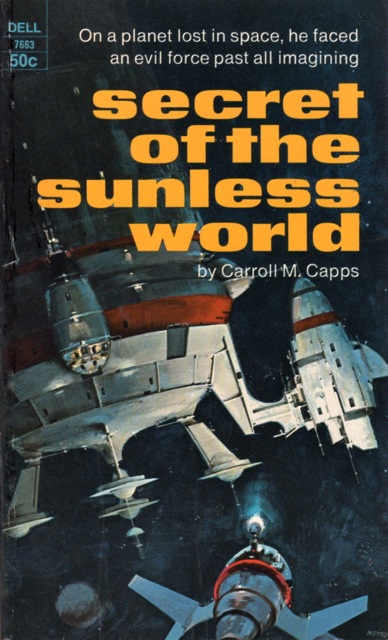

Secret of the Sunless World, by C. C. MacApp

American writer C. C. MacApp also has a fast hand at the typewriter, often showing up in If. He's been reviewed a lot here, generally getting three stars. Sometimes less, sometimes more. (Sounds a lot like Tubb, doesn't he?) Will his latest novel be below average, above average, or just plain average?

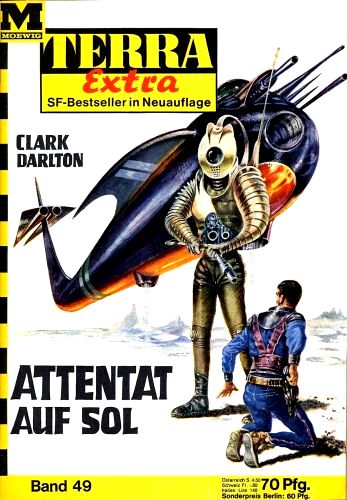

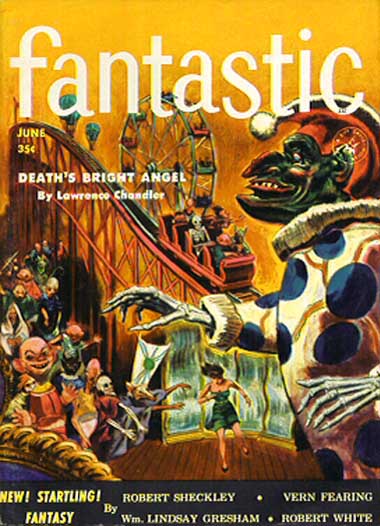

Cover art by John Berkey.

Wait a minute! I hear you cry. I thought we were talking about MacApp, not this Capps person!

Yep. C. C. MacApp is actually Carroll Mather Capps in real life. If you'll open the book, you'll see it's been copyrighted in the name of C. C. MacApp. Don't ask me why his real name is on the cover.

Anyway, our hero is an Earthman who caught an alien disease somewhere in space. Before killing him, it's going to make him blind. The good news is that some friendly, semi-humanoid aliens are willing to take him to a place where he can be cured, if he undertakes a mission for them. (The aliens recently arrived in the solar system and have the knowledge of faster-than-light travel, but haven't let humans in on the secret.)

His mission is to track down a renegade alien who kidnapped an alien scientist and stole a powerful piece of ancient technology from a species of extraterrestrials who vanished long ago. In order to do this, the aliens take him to a planet without a sun (hence the title) which is able to support life due to its internal heat.

His contact is a multi-tentacled space pirate with two snake-like heads. This roguish character takes him to a hospital, where a spider-like surgeon operates on his eyes.

Wouldn't you know it? There's a catch. The pirate blackmailed the surgeon into doing something to our hero's eyes so that he needs routine treatment with a certain chemical in order to keep his vision. As a side effect, the operation gave him the ability to see clearly in almost total darkness, even able to perceive radiation. This makes him a very useful tool of the pirate on this planet without natural illumination except starlight.

The guy goes along with the pirate, while also spying on him. Meanwhile, the local inhabitants of the planet spy on both him and the pirate. (There's a lot of spying in this book.) The renegade alien and the kidnapped victim show up, as well as other aliens intent on conquest.

I've only given you a synopsis of maybe half the novel. There are plenty of complications in store. The hero winds up on yet another planet, and finds out about the ancient vanished aliens.

The main difference between Tubb's book and this one is that McApp's is much more tightly plotted. There aren't any pointless subplots. As a bonus, the octopus-like pirate is an enjoyable character, usually several steps ahead of the hero. Not the most profound story ever told, but competent entertainment.

Three stars.

by Tonya R. Moore

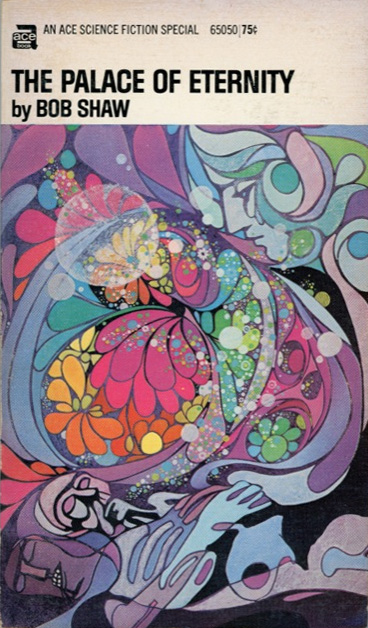

The Palace of Eternity, by Bob Shaw

The Palace of Eternity is the first of Bob Shaw’s works that I’ve read. Shaw is a man of many talents, having worn a myriad of hats from taxi-driver to structural engineer and aircraft designer. He has added writing fiction to his repertoire with works such as The Two Timers, Night Walk, and his breakout short story, "Light of Other Days."

The Palace of Eternity is set in a distant and turbulent future where humanity has discovered FTL space travel, taken to the stars, and struggles to weather the onslaught of violent attacks from an alien species known as the Pythsyccans.

The protagonist, Mack Tavernor, is a battle-hardened former soldier who had been orphaned when the Pythsyccans devastated his childhood home. Naturally, Tavernor doesn’t view the Pythsyccans in a positive light but he also seems disillusioned enough with humanity to keep his own kind at arm’s length.

The Pythsyccans attack Mnemosyne, an idyllic, almost utopian world dubbed a haven for writers, artists, and other creators of varied talents. Tavernor, naturally, takes up arms against the invading enemy and dies in battle. This is where the story takes an interesting turn.

After shucking this mortal coil, Tavernor encounters the egons, a non-corporeal race of cosmic beings whose very existence is threatened by the proliferation of humanity’s FTL-ramjet technology, the Butterfly Ships. Tavernor, the newest egon, gets another lease on life, inhabiting the body of a newborn human child named Hal. The goal of his mission, to somehow interfere in the war between the humans and Pythsyccans in order to save the endangered egons.

The Palace of Eternity is a fantastic and eloquently written and fast-paced story that fires on all pistons where the things about science fiction that excite me are concerned. And yet…somehow, though, this book failed to move me. For all its eloquence and imaginativeness, I found myself unable to feel strongly about the characters and events of this story. It failed to fill me with a sense of wonder, even amidst the wondrous imagery. At first, I couldn’t put my finger on why.

It wasn’t just that much of the story felt glossed over—and probably should have been explored in greater detail. My main source of dissatisfaction was with the story’s main character’s development.

Mack Tavernor is admirable. He's truly a man's man in all the ways a man ought to be a man. Yet, I could not bring myself to either like or dislike him. At no point did I become emotionally invested in the things that happened to and around him. In short, as a protagonist, Mack falls flat. Lacking the kind of depth and complexity that makes fictional characters feel real in my mind, he is like soda pop that has lost its fizz.

Had Mr. Shaw given The Palace of Eternity the extent of thought and care it deserved, the book could have turned out to be a true phenomenon. It is, indeed, still an excellent and worthy read. Even so, I feel it's almost a tragic waste of the author's very clear intellect and truly wondrous imagination.

4 out of 5

by Jason Sacks

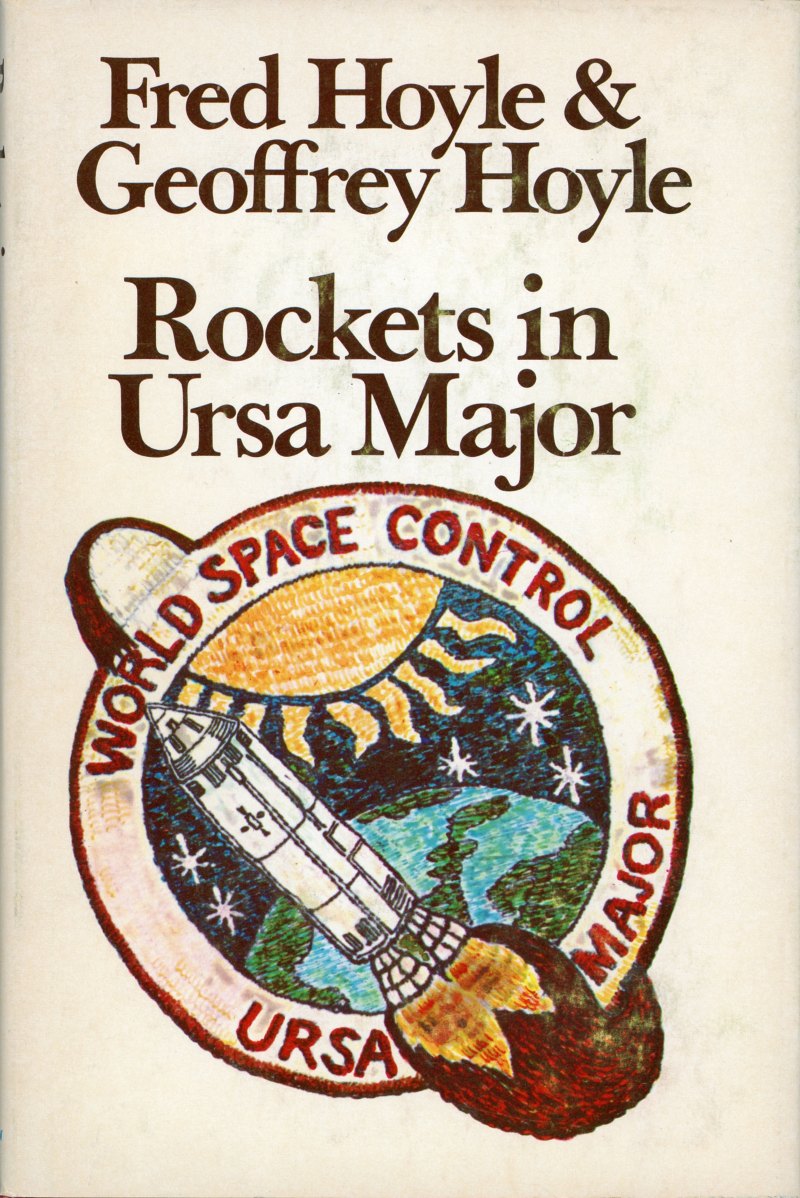

Rockets in Ursa Major, by Fred Hoyle & Geoffrey Hoyle

This is my first encounter with the fiction of the British cosmologist Fred Hoyle. A prominent astronomer with a long tenure at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge, Hoyle is perhaps best known for a slew of rather controversial opinions. For instance, Dr. Hoyle has rejected the idea of the Big Bang, and for many years has promoted the idea that life on Earth began in the stars.

Yes, he is an eccentric, but Dr. Hoyle is quite a genius, really; a thoroughly unique figure and someone I would really enjoy meeting.

Dr. Hoyle is also a prominent science fiction writer. In collaboration with his son Geoffrey, he recently authored Rockets in Ursa Major, a thoroughly entertaining, if too brief, science fiction yarn reminiscent of the sort of thing which John W. Campbell might have published. If your kind of space fiction involves brilliant and fearless scientists battling bueaucracy and evil aliens, Rockets in Ursa Major is your kind of book.

I kind of giggled a bit when I realized the main characterof Ursa Major is a deeply accomplished and slightly eccentric scientist and that the book is told in first person – do you look in the mirror a bit too much, Dr. Hoyle? As the story begins, the genius Dr. Richard Warboys is at a very boring professional conference when surprising news pops up on the telly: a spaceship which has been lost for thirty years has suddenly reappeared, streaming towards Earth’s atmosphere.

Only a brilliant scientist can help the ship land! And only a brilliant scientist can help discover the ship's great secret of invading alien species! And only a brilliant scientist can fly a seeming suicide mission to battle those invaders! And only a brilliant scientist can figure out a complicated way to use solar flares to defeat those invaders! And, you guessed it, only a brilliant scientist can then fly towards the sun, release those solar flares and save our planet.

Are you shocked if I tell you that scientist's name is Dr. Dick Warboys?

So, yes, the plot of Rockets in Ursa Major is pure wish fulfillment: the 54-year-old Dr. Hoyle cast a genius scientist aged in his mid-30s as the man who basically singlehandedly saves Earth. And it’s all rather silly.

But Rockets is all tremendously fun, too, in that marvelously light-hearted way one might imagine Campbell publishing next to a Heinlein juvie or van Vogt brain-twister. I’m not sure if it’s the influence of the younger Mr. Hoyle the author, but this book moves at a kinetic speed, with almost too many twists and turns in its breathless style (I’m not sure why we needed a sequence in which Dr. Warboys breaks into the research college by stealing a boat and running through tunnels, for instance).

At the end of this book, the Hoyles hint at the possibility of a sequel. I would enjoy another thoroughly light-hearted and thoroughly indulgent visit with Dr. Warboys.

3 stars.

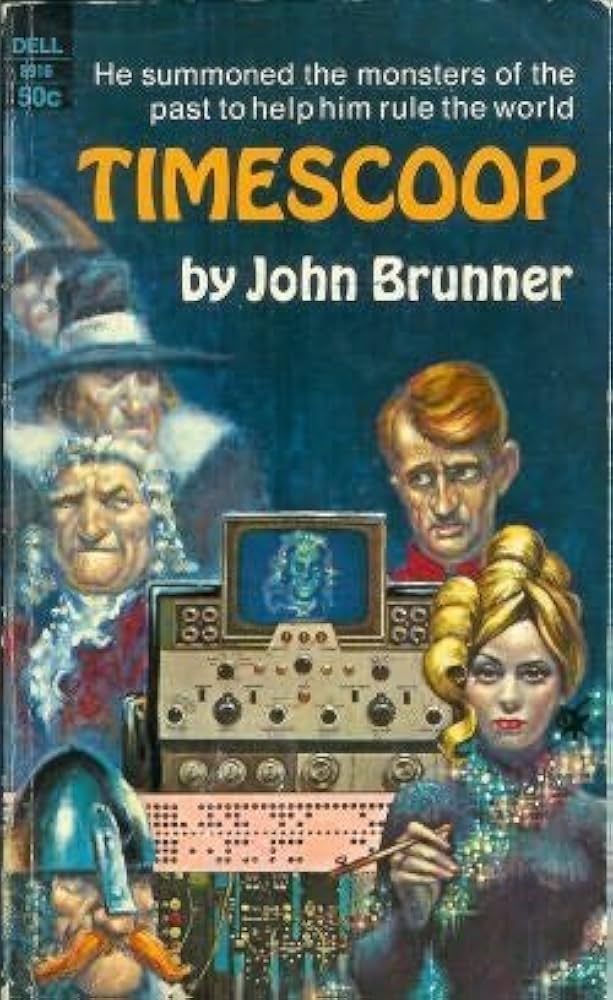

Timescoop, by John Brunner

John Brunner is one of the most prolific science fiction authors of the latter half of this decade, to the extent that it sometimes feels hard to keep up with his work. I’ve always enjoyed Brunner’s work, which often manages to tread a fine line between smart concepts and exciting action. And I was a huge fan of his grand step into literary science fiction, the remarkable Stand on Zanzibar.

This month sees the release of a new Brunner, called Timescoop, but the zines are already reporting the autumn '69 release of another Brunner novel, called The Jagged Orbit [Actually, it's already been released—the Autumn release is a re-release (ed.)]. Based on the blurbs, Orbit sounds like another book of strong literary ambitions.

Timescoop, however, is not a novel of strong literary ambitions. It’s a goof, a novel in which Brunner played with some clever ideas and delivered a quick little satirical piece. Timescoop clears the palette between works of deep seriousness.

Our protagonist here is one Harold Freitas III, a self-obsessed inheritor of his family’s fortunes who is looking to live up to the legacy his father, recently deceased, has left to him.

Fortunately for Freitas, an amazing invention called the Timescoop has been invented, and he has control of it. The Timescoop can bring anything forward in time and allow it to live in the book’s present. Thus the Venus de Milo and Hermes of Praxiteles can exist – with their original arms – and so can people.

Looking to make a mark with publicity, Freitas brings forward nine of his ancestors in time and brings them to a family reunion broadcast throughout the galaxy. After all, men of the past were men of great virtue and character and the future world can learn from their insights. But… as one character states prophetically… “How much do we really know about these people? One always looks at the past through rose-colored –"

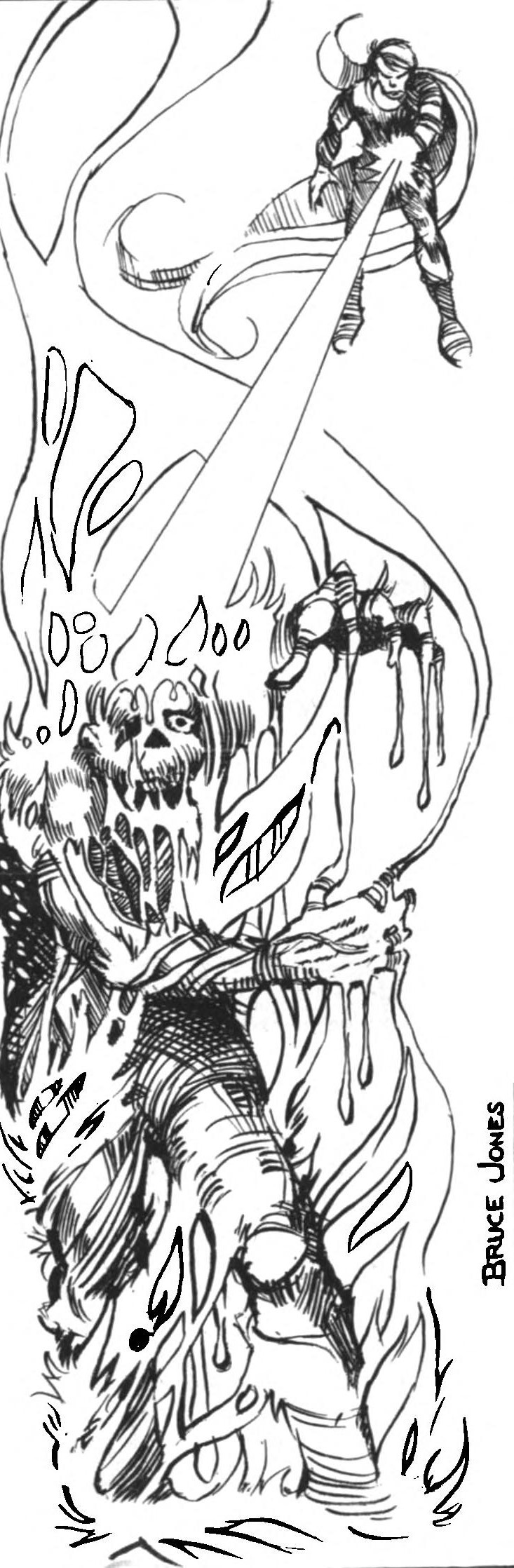

So Freitas brings forward nine of his ancestors – a steadfast medieval king and a medieval Crusader and a 17th century British merchant and a fire-and-brimstone preacher and a female cowboy, among others – and readies them to face the world and make Freitas famous.

But be careful what you wish for, and especially be careful what you create. Because these ancestors are not the good people Freitas wishes they could be. They are pederasts and nymphomaniacs, gluttons who are covered with filth and who have ancient racist attitudes. One even indulged in the slave trade.

Most of this is played for laughs, and it’s easy to imagine someone like Peter Sellers or Alec Guiness playing all the roles in a film adaptation, taking on silly voices while someone like Peter Cook keeps rolling his eyes at the chaos.

But there is also a small element of satire, a small joy at bringing down the rich and pompous and allowing their obsessions to blow up in their faces.

Timescoop is another quick little novel, and at a mere 156 pages it doesn’t wear out its welcome. But this is clearly Brunner relaxing and doing a small warmup for his next literary work.

3 stars.

Light a Match

by George Pritchard

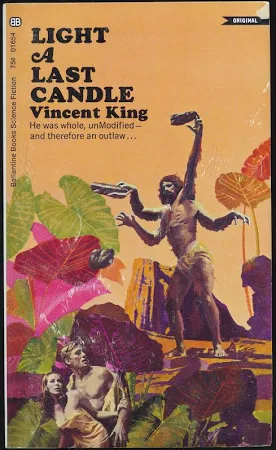

Light a Last Candle, by Vincent King

In my first conversations with the Traveller, I was warned that some of the works I would cover here would be unpleasant. This is my first, and it does not even have the decency to be memorably terrible (Ole Doc Methuselah by L. Ron Hubbard), or bland yet competent (One Against Herculeum by Jerry Sohl). Light A Last Candle is knockoff Heinlein, wrapped in knockoff Doc Smith and shot through with attempts at imitating Bester.

Our main character is one of the few remaining humans on a planet. There’s “Mods” — modified humans — which our main character doesn’t like. Like a low-energy Gully Foyle, he doesn’t like anyone or anything very much. He doesn’t have a name, our main character, nor does “the girl”. She’s lucky, as all other female figures are called Breeders. The character our main character can stand the most is an old, fatherly figure simply referred to as Rutherford. They are the only two original humans, Free Men, left on the planet, which is mostly under the mind control of the Aliens, and their Mod slaves…or are they?

Social commentary is attempted, as are twists, and like in The Devil’s Own by Nora Lofts, the revelations provided to the reader are ultimately shallow. The more they appear, the more insignificant they are revealed to be. The Devil’s Own is in fact a rather poor comparison; since that is a fine book. In truth, the story Light A Last Candle most reminds me of is Cat-Women of the Moon (1953), with its clunky twists, bland characterization, pervasive male chauvinism, and failing to convey travel in a story that is ostensibly all about traveling. Distance is compressed like an accordion, details are skipped over, days pass offhandedly when we could be learning more about anything we are reading. This ultimately becomes a paucity of both showing and telling, which certainly is new to me. Like Star Man’s Son by Andre Norton, the book centers around bringing the reader to encounter different cultures in this alien future. Like The Weirdstone of Brisigamen by Alan Garner, that travel also takes place in tight, dangerous caves. In both of those books, however, distance and time were characters in themselves. You felt the pressure of travel, the hard work the characters put in, their sense of purpose.

The only talent that really appears throughout the work is a pervasive sense of disgust, of fleshy horror that I know William Hope Hodgeson in The Derelict and Arthur Machen in The Three Imposters did better sixty years ago. I think it's this author's first book, but his grouchiness is beyond his years.

I am writing this review as quickly as possible, because after finishing this book less than a half an hour ago, it is rapidly leaving my mind. I have filled this page with references to other works, so that the reader may enjoy books much better than this one.

One star.

![[July 16, 1969] Not all Jake(s) (July 1969 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690716covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 14, 1969] Odyssey On Two Wheels (<i>Easy Rider</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/TITLE-672x372.png)

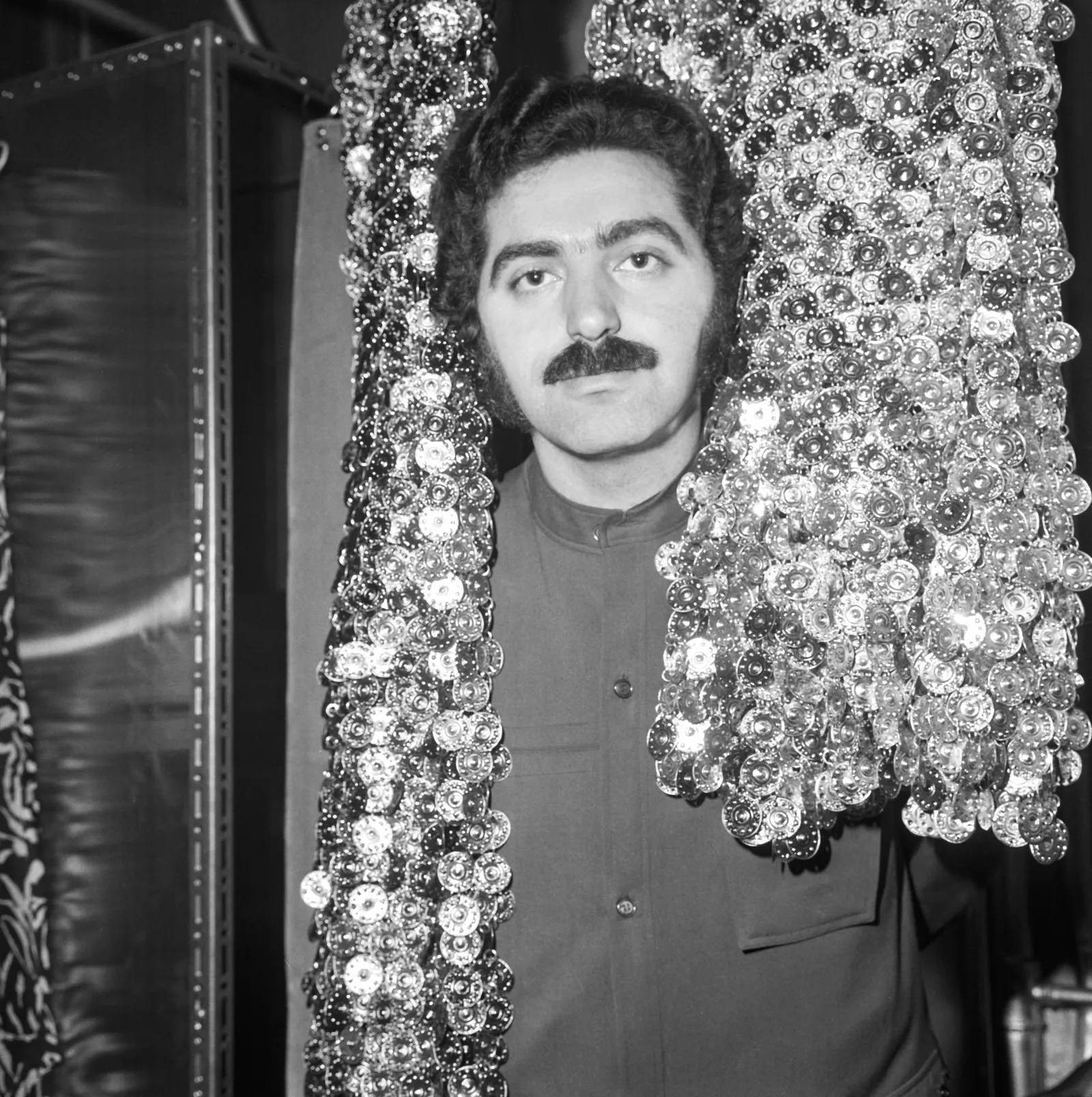

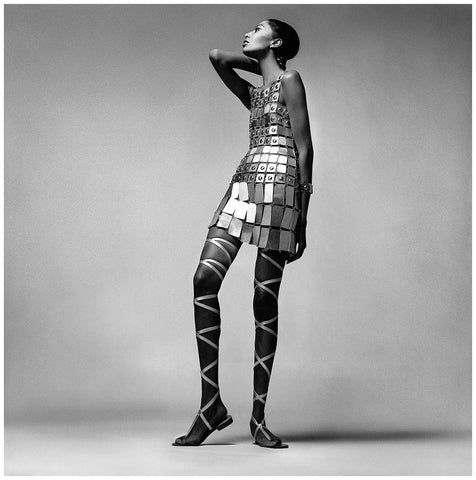

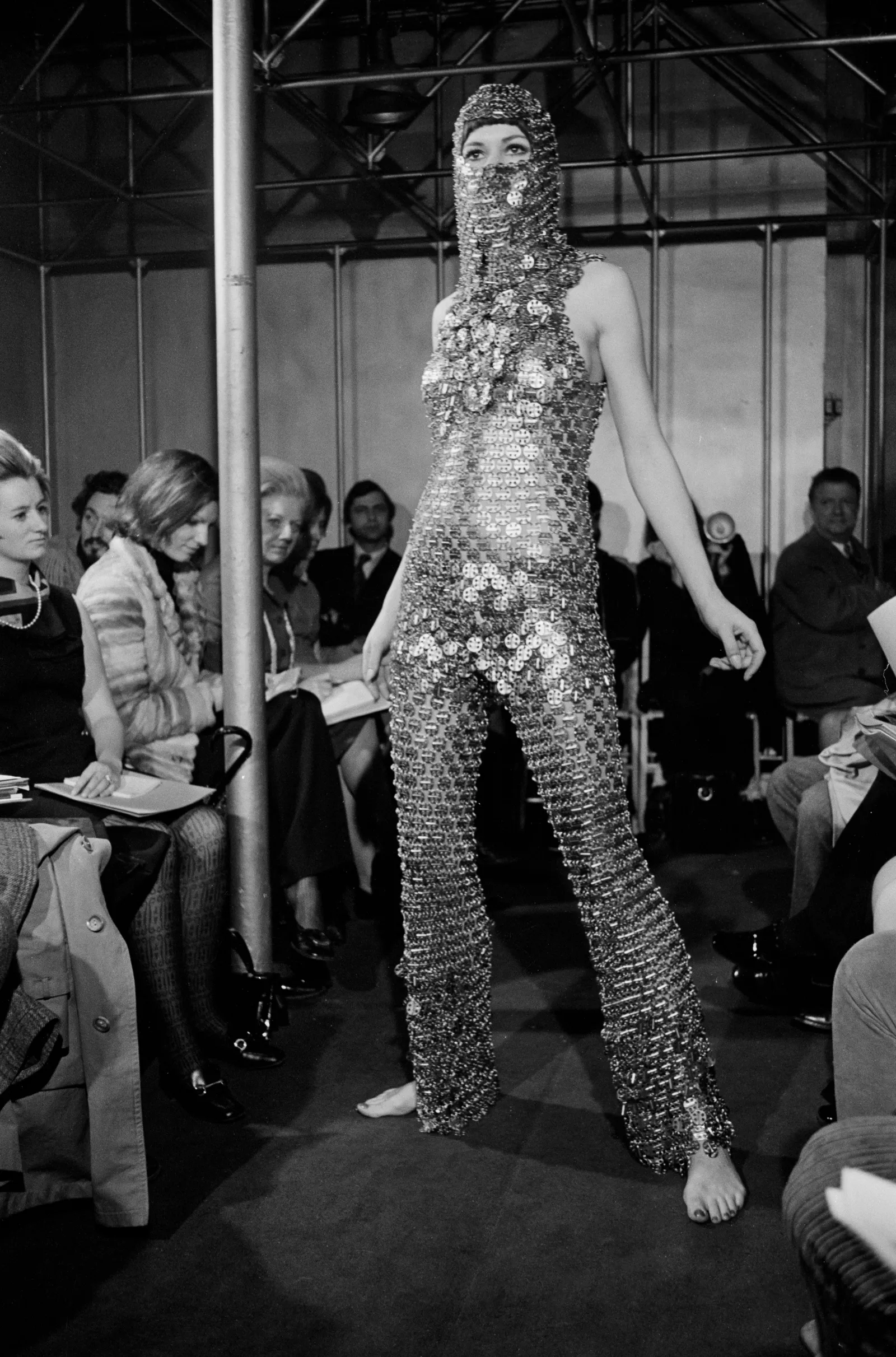

![[July 12, 1969] Paco Rabanne and the Theater of War](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Francoise-hardy-in-Rabanne-60s-500x372.jpg)

![[July 10, 1969] Sex! Now That I Have Your Attention . . . (August 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1969] Nowhere fast (August 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690708galaxycover-450x372.jpg)

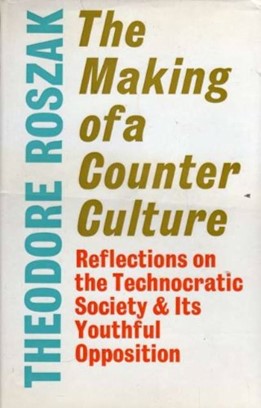

![[July 6, 1969] Everybody's talking about Revolution, Evolution… (The Making of a Counter Culture by Theodore Roszak)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/CC1-261x372.jpg)

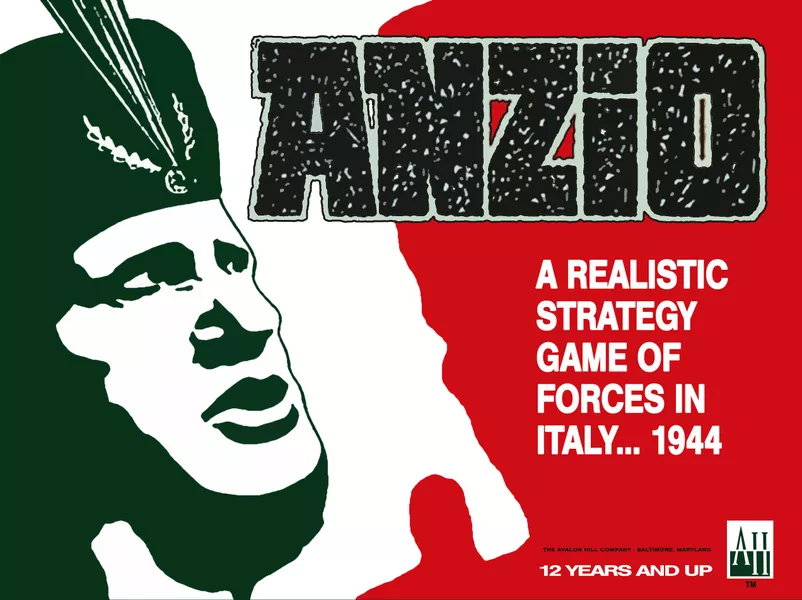

![[July 4, 1969] When Joey goes over the top… (Avalon Hill's <i>Anzio</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690704anzio-672x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1969] Merging streams (August 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Venture-1969-08-Cover-543x372.jpg)

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner![[June 30, 1969] Anywhere but here (July 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/690630analogcover-656x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1969] I Don’t Have Your Wagon (Review of “The Maltese Bippy”)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/The_Maltese_Bippy.jpg)