by Gideon Marcus

Live from Miami Beach!

If you, like Walter Cronkite, Chet Huntley and David Brinkley (and me), soldiered through the four days and nights of GOP convention coverage, you saw the drama unfold in Miami Beach as it happened. Dick Nixon came into the event a "half-inch" shy of having the nomination sewed up, his chief competition coming from New York governor Nelson Rockefeller. California governor Ronald Reagan, best known for his Chesterfield cigarette ads, coyly denied that he was a candidate…until he suddenly was, in a desperate bid to court "the New South".

The suspense was all a bit forced. By Day Two, it was understood that the New Jersey delegation, which had been putatively firm in supporting native son Senator Clifford Case through the first ballot so as to be able to play kingmaker later on, was now breaking for Nixon. On Day Three, South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had expressed that his first and second choices were Ronald Reagan, suddenly declared his support for Nixon.

And so, after endless seconding speeches for candidates who had no intention of being President, like Governor Hatfield of Oregon and "dead duck" Governor Romney of Michigan, Nixon won on the first ballot.

After that, the only unknown was who would be his running mate. The South made loud objections to any GOP liberals being tapped, like New York mayor John Lindsay and Illinois Senator Charles Percy. The smart money was on a Southerner like John Tower of Texas or Howard Baker of Tennessee. So everyone was surprised when Maryland governor Spiro Agnew got the nod at a press conference the morning of Day 4, overwhelmingly winning the ballot that night (though not without loud protest from Romney's Michigan contingent).

Why Agnew? Here were a couple of comments from the NBC reporter pool after the convention:

"It's not that Agnew adds anything to the ticket; it's that he doesn't take anything away."

"Everybody loves Agnew–no one's ever heard of him!"

Agnew, who is kind of a Southerner, and kind of a liberal, but who has recently come out in favor of strong "law and order" (which means urging cops to shoot Baltimoreans if they steal shoes), will enable Nixon to retain his chameleon qualities while Agnew acts as attack dog. And since being the actual Vice Presidency is worth exactly one half-full bucket of warm piss, it doesn't really matter that Agnew is brand new to large scale politics.

Long story short, Nixon is the One, which we've known since February. God help us all.

Live from New York!

When Galaxy first appeared in 1950, it was also "the One", breathing fresh new air into the science fiction genre. 18 years later, it is still a regular on the ballot for the Hugo Award. Last month's was a superlative issue; does this month's mag maintain that level of quality?

cover by Jack Gaughan

Nightwings, by Robert Silverberg

Silverbob presents a richly drawn future world, one in which humanity has soared to great heights only to stumble back to savagery twice. Now, thousands of years later, Earth is in its Third Cycle. The planet is an intergalactic backwater, and its people are rigidly divided into castes.

Our heroes are a Watcher, a Flier, and a Changeling. The first, whose viewpoint we share, is an aged itinerant, hauling in a wagon his arcane tools with which he clairvoys the heavens three times a day (or is it four? The author says both.) for any signs of an alien invasion. The Flier Avluela, the only woman in the story, is a spare youth who is able to soar on dragonfly wings when the cosmic wind is not too strong. And finally, there is Gorman, who has no caste, yet has such a broad knowledge of history that he could pose as a Rememberer.

art by Jack Gaughan

All roads lead to Rome, so it is said, and indeed the three end up in history-drenched Roum, where the Watcher finds the city overcrowded with his caste. The cruel Prince of Roum, a Dominator, takes a shine to Avluela, compelling her to share his bed. This incenses Gormon, the crudely handsome mutant, who vows his revenge.

Gormon has the advantage of knowing that justice will not be long delayed–the alien invasion is coming, and he is an advance scout…

There's something hollow about this tale, rather in the vein of lesser Zelazny. Oh, it's prettily and deliberately constructed, but the story's characters are merely observers rather than actors. The stage is set and the inevitable happens. When the alien conquest occurs, it is our Watcher who sounds the alarm, but it is implied others were about to do so (why they did not cry out the night before when the invasion first became apparent is left an inadequately explained mystery). It's a story that doesn't really say or do anything.

Beyond that, I object to the lone female existing to be loved and/or raped, depending on the man involved. She is there to be a pretty companion, a object of pity, a tormented vessel. I suppose the small mercy is she is not also a harpy, as Silverberg is occasionally wont to present his women.

Anyway, I give it just three stars, but I imagine it'll be a Hugo contender next year…

When I Was Very Jung, by Brian W. Aldiss

art by Brock

A weird mix of sex, cannibalism, and archetypes. I found it distasteful and out of place.

One star.

Find the Face, by Ross Rocklynne

One of science fiction's eldest veterans offers up this romantic piece. It has the old-fashioned narrative framework, with an aged tramp freighter captain describing the day he was contracted by a wealthy widow, and what ensued afterwards. The widow's husband and family had been lost in a space accident, but somehow, his face remained, etched across the sky in cosmic clouds and star clusters. The widow saw this phenomenon once, and she was determined to find from what vantage in the universe it could be reliably observed again.

The captain, meanwhile, was looking for Cuspid, the planet whence the green horses that sired his favorite racer came. Together, they went off on their separate quests, and in the process, found the one thing neither had been looking for: new love.

It's something of a mawkish story and nothing particularly memorable. That said, it is sweet, almost like a romantic A. B. Chandler piece, and I appreciated the two characters being oldsters rather than spring chickens. Moreover, these were not ageless immortals, but silver-haired and wrinkle-faced septuagenarians.

More of that, please. Three stars.

The Listeners, by James E. Gunn

art by Dan Adkins

In the early 21st Century, Project Ozma continues, despite fifty years of drawing a blank; even with the efforts of dozens of astronomers, hundreds of staff, and the entire survey calendar of the great Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico, not a single extraterrestrial signal has been encountered. Low morale and lack of purpose are the rule amongst these dispirited sentinels.

This is an odd story, with much discussion and development, but no resolution. At times, the author hints that a message is forthcoming, or maybe even already being received, if only the listeners could crack the code to understand it. But the climax to the tale has little to do with the story's backbone, and, as with Nightwings, the characters drift rather than do.

It feels like the beginning of a novel, not a complete story. Larry Niven could probably have done a lot more with the piece in about half the space.

Three stars.

For Your Information: Mission to a Comet, by Willy Ley

Now this piece, I dug. Willy Ley talks about why comets are important to understanding the early history of the solar system, and which ones could feasibly be approached with our current rocket and probe technology. The little chart with all the astronomical details of the Earth-approaching comets was worth the piece all by itself. I particularly liked the idea of Saturn for a "swing-around" mission to catch up with Halley's Coment from behind!

We truly live in an SFnal reality. Five stars.

The Wonders We Owe DeGaulle, by Lise Braun

art by Brock

Newcomer Lise Braun offers up a droll travel guide to a mauled Earth. It seems a French bomb that exploded in Algeria sundered our planet's crust, sinking half the Americas and turning the Sahara into a stained glass plain.

It's mildly diverting but Braun's clumsy writing shows her clearly a novice. I think the setting would have served better as background than a nonfact piece.

Two stars.

A Specter is Haunting Texas (Part 3 of 3), by Fritz Leiber

art by Jack Gaughan

Lastly, the conclusion to Leiber's latest serial, a sort of fairytale version of a hard science epic. The "Specter" is really a spaceman named de la Cruz, a gaunt, eight-foot figure kept erect by an electric exoskeleton, denizen of a circumlunar colony. He has been the centerpiece of a Mexican revolution, which is trying to throw off the literal yokes (cybernetic and hypnotic) forced upon the Mesoamerican race by post-Apocalyptic Texans. The spaceman's comrades include two quite capable and comely freedom fighters, Raquel Vaquel, daughter of the governor of Texas province, and Rosa ("La Cucaracha"), a high-spirited Chicana; then there's Guchu, a Black Buddhist, reluctantly working with the ofays; Dr. Fanninowicz, a Teutonic technician with fascist sympathies; Father Francisco; and El Toro, a charismatic leader in the revolution.

In this installment, de la Cruz finally makes it to Yellow Knife, where he wishes to lay claim to a valuable pitchblende (uranium) deposit. Unfortunately, the Texans have gotten there first–and what they have established on the site finally reveals just what all those purple-illumined towers they've been planting across the North American continent are for. 'T'ain't nothin' good, I can assure you!

Last month, I read a fanzine where someone complained that this was a perfectly good story ruined by being turned into a tongue-in-cheek fable. Certainly, I felt the same way for a while. By Part II, however, I was fully onboard. While this last bit didn't thrill me quite as much as the middle installment, it's still a worthy novel overall. When it comes out in paperback, pick it up.

Four stars for this section and for the serial as a whole.

art by Jack Gaughan

Roll Call

Like the Republican convention, the outcome seemed certain, but a few twists and turns along the way did create a bit of doubt. But in the end, if this month's Galaxy is perhaps not all the magazine we hoped it would be, nevertheless, it's one we can live with.

For the time being, Galaxy remains The One. May it continue to be so for four more years.

![[August 12, 1968] <i>Galaxy's the One</i>? (the September 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680812cover-1-scaled.jpg)

![[August 10, 1968] First Trans-Oceanic Fan Fund Brings Fandom Together](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680810shibano2-672x372.jpg)

![[August 8, 1968] The Little Witch Girl and The Little Ghost Boy (<i>Mahoutsukai Sally</i> and <i>GeGeGe no Kitaro</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680808sally2-672x372.jpg)

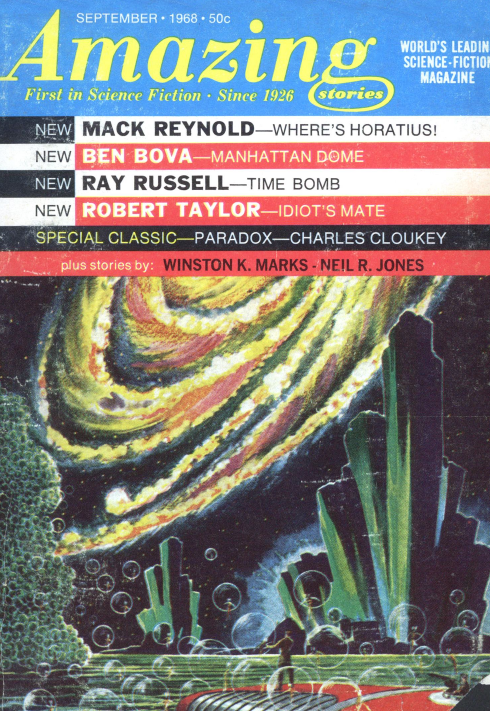

![[August 6, 1968] Treading Water (September 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/amz-0968-cover-490x372.png)

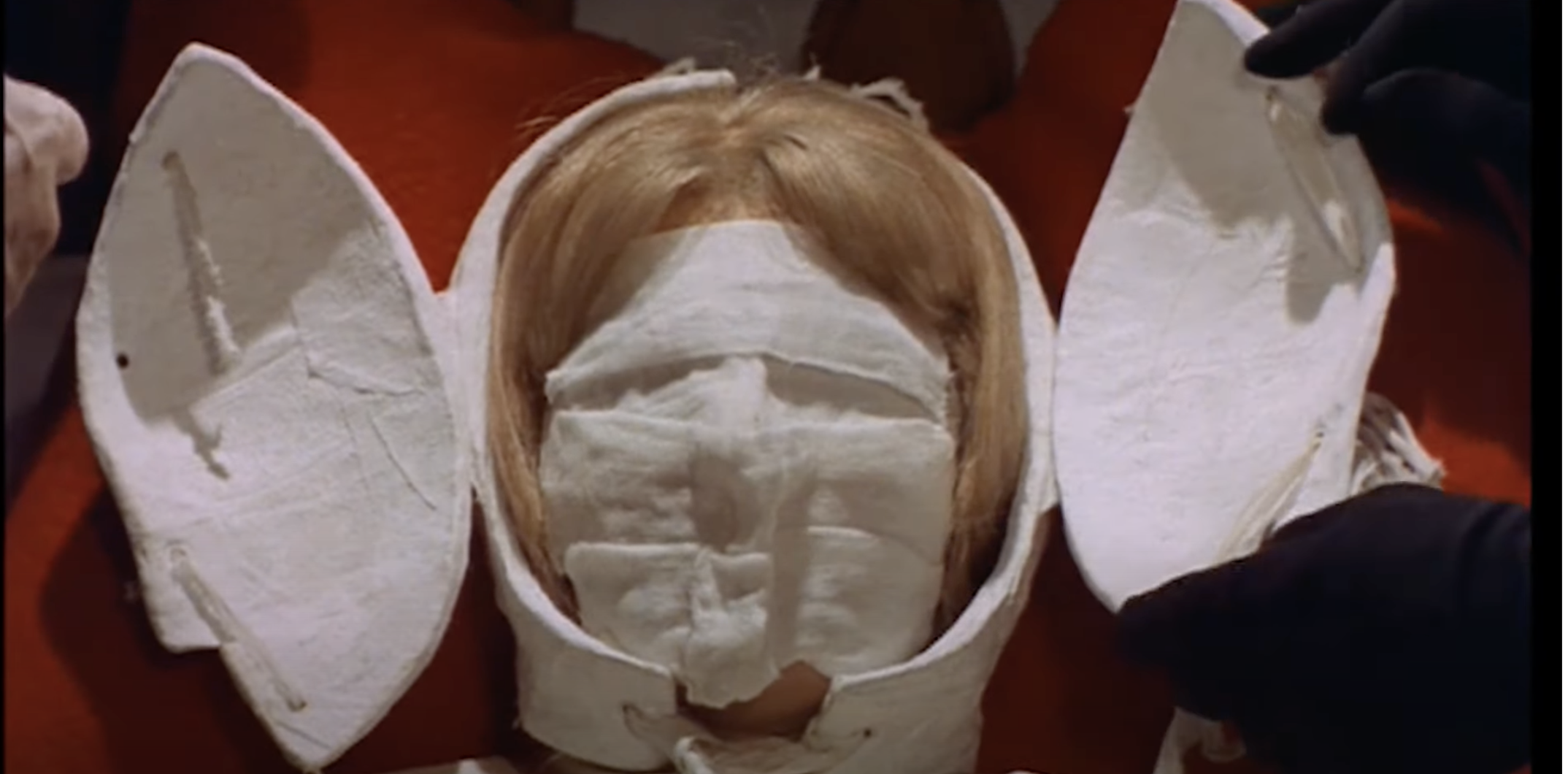

![[August 4, 1968] Changing Tastes (<i>The Year of the Sex Olympics</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Olympics6.png)

![[August 2, 1968] Dreams and Nightmares (September 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/IF-1968-09-Cover-672x372.jpg)

Red Guard rebels march in Shanghai last year.

Red Guard rebels march in Shanghai last year. Those are supposed to be radiators, not rocket thrusters. Art by McKenna

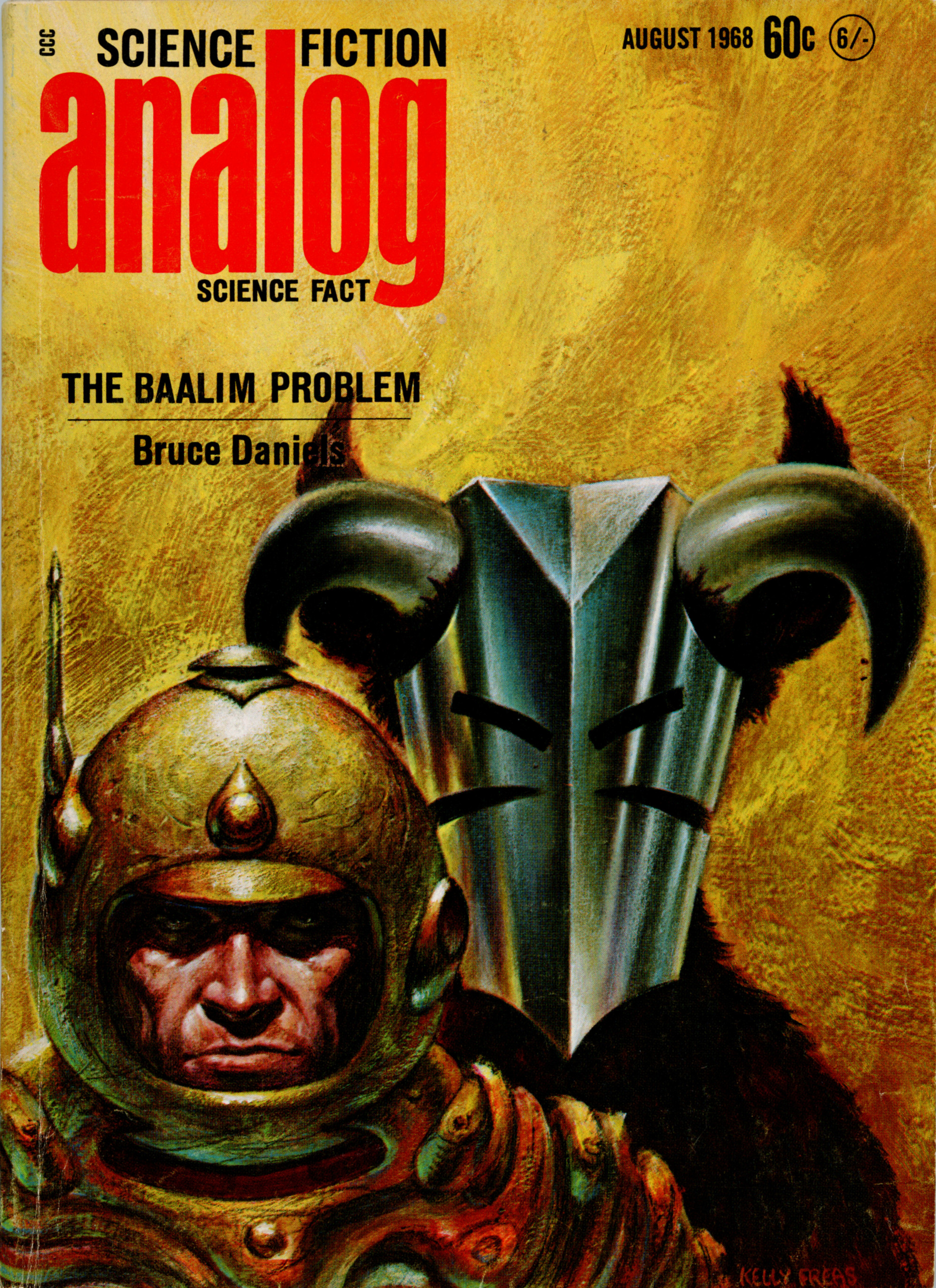

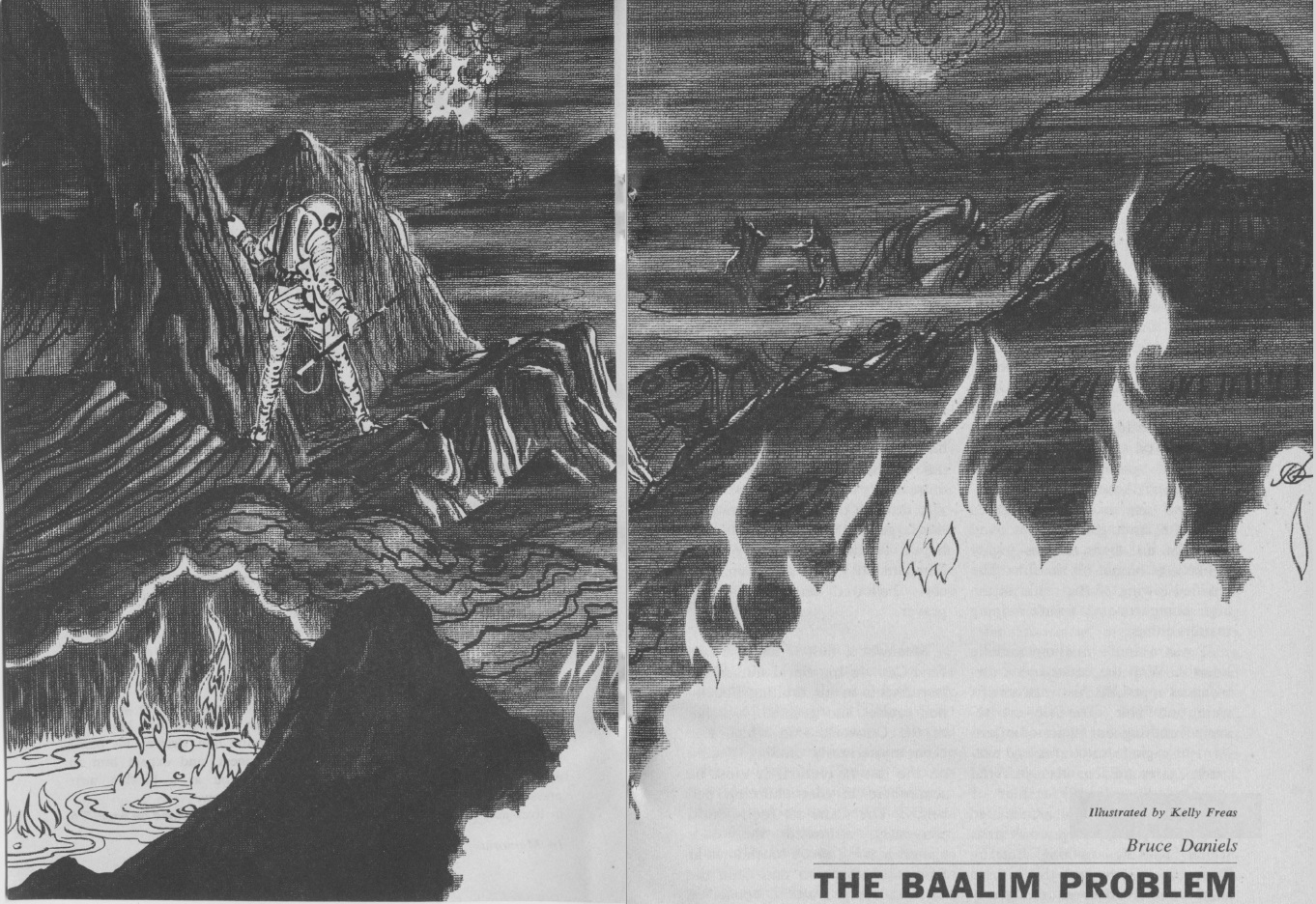

Those are supposed to be radiators, not rocket thrusters. Art by McKenna![[July 31, 1968] No easy answers (August 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680731cover-672x372.jpg)

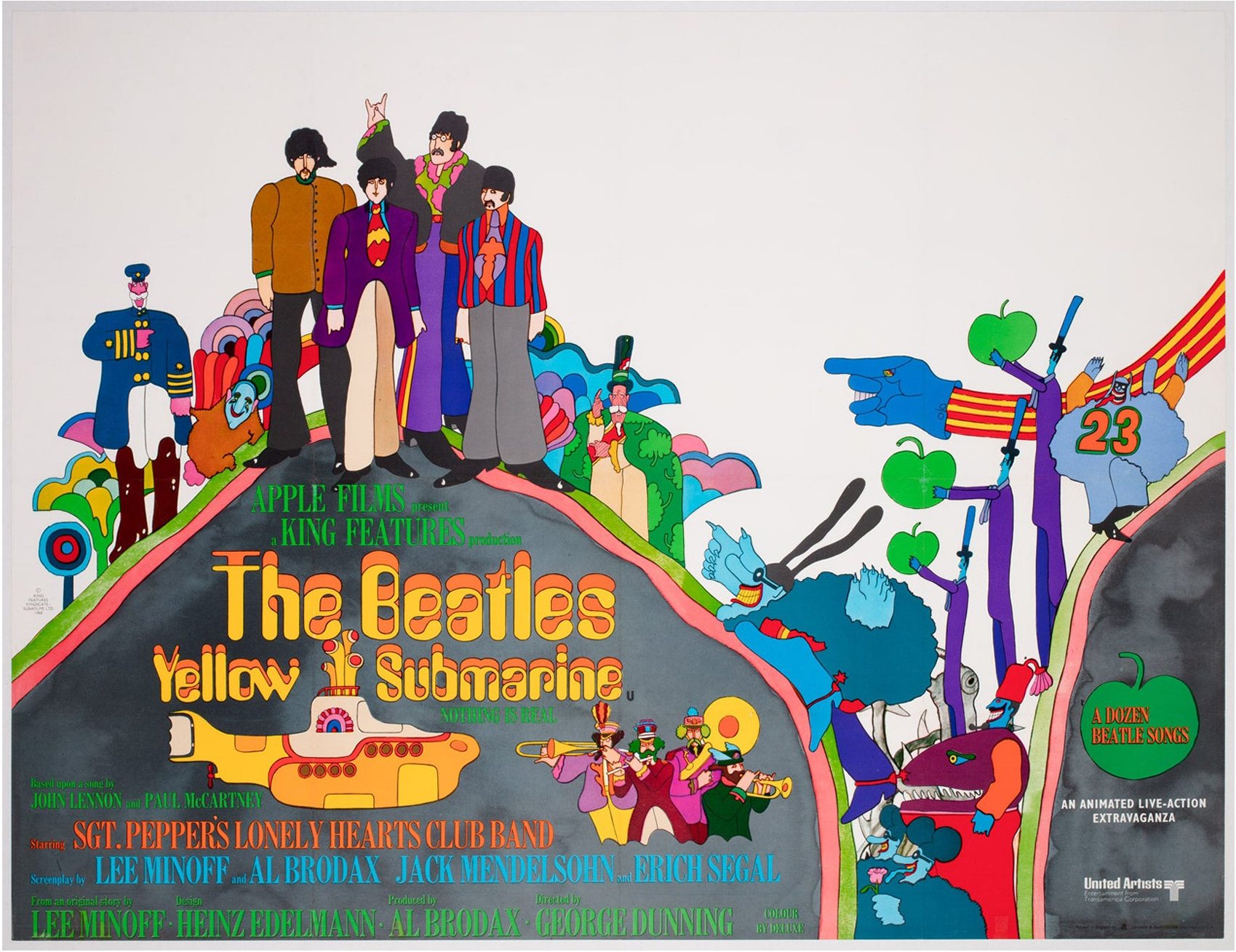

![[July 28, 1968] Once Upon A Time, Or Maybe Twice… (Yellow Submarine)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680728poster-672x372.jpg)

![[July 26, 1968] A lost pair of hours… (<i>The Lost Continent</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680726poster-672x372.jpg)

![[July 24, 1968] Peter Cushing and the Women (<em>Frankenstein Created Woman</em> and <em>The Blood Beast Terror</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680724posters-601x372.jpg)