by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

Do you remember in my article last month when I summed up by saying that Science Fantasy was all new writers of limited readability and New Worlds relied on its cohort of now fairly well-established writers?

Well, the Editors were clearly listening to me (as if!), as this month they've swapped positions. We have some major changes this month in both magazines.

Let’s start with the issue that arrived first in the post this month: the July issue of Science Fantasy.

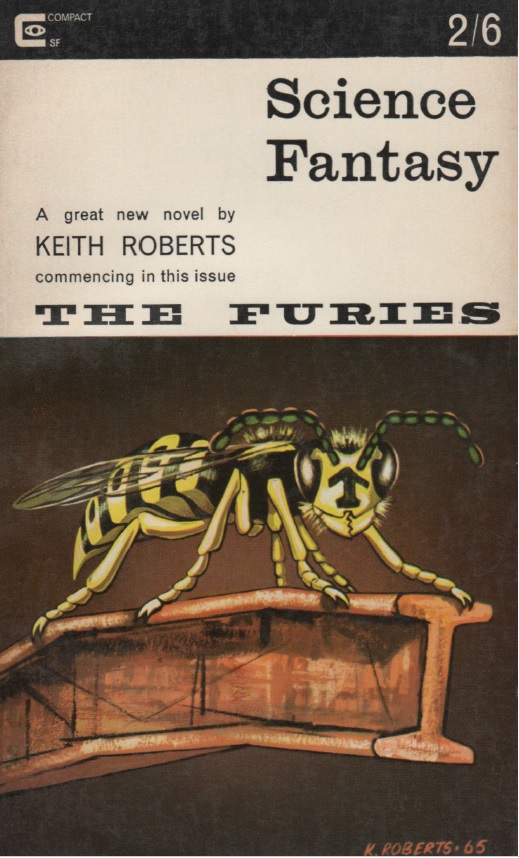

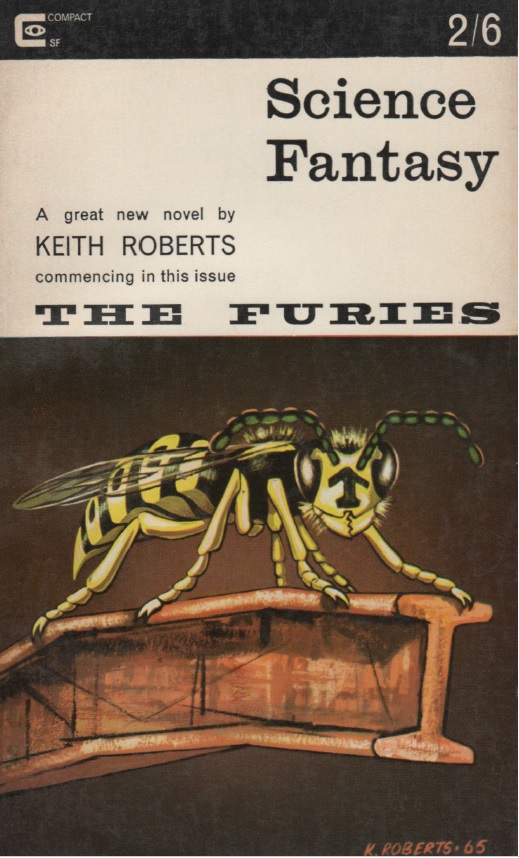

Well, it is Summer here and the latest cover by the prolific Keith Roberts reflects that.

I must admit that (for a change) I actually like the painting of this cover, although the subject matter is one I personally dislike – I hate wasps. But it does what the cover is meant to do, which is make you interested in the issue. It also refers to Mr. Roberts’s new novel, the first part of which fills this issue. More later.

Onto the editorial, which continues the discussion Kyril started last issue – which was “The job of a critic consists of knowing when he is being bored, and why", or rather that of the importance of readability when discussing or – heaven forbid! – criticising prose. In this issue we get more to the point, when Kyril suggests for the SF community “our sort of fiction has its roots firmly in the pulp magazines and since these survive by the casual, non-enthusiast readers and not by the relatively few ‘fans’, readability must be a major consideration.” I think he has a point, although the New Worlds way, currently under the guidance of Mike Moorcock seems to want to change that by producing more challenging and less linear prose than that. Some might say less readable.

He then goes on to say that science fiction is shackled by its own conventions in as much of a way as the detective novel is. He finishes with a gloomy prophecy, that “…when I look at the future through the bottom of my ale-glass I can see about as much hope for the future of science fiction as we have known it as there is for the detective-novel unless this insistence on novelty relaxes. It cannot hope to be accepted as part of the mainstream whilst bound by the conventions more rigid than the ones it claims to be destroying.”

So: we must change, or die, move on from the past to form a new future. Yet remain readable. There’s a rallying manifesto for the New Wave if ever I saw one. It’s been said before by both Kyril and Moorcock but this lays itself out clearly, presumably for those new readers.

To the stories themselves.

The Furies (Part 1 of 3), by Keith Roberts

You might have noticed my comments about Roberts in the past few months, whether under his own name or a pseudonym (I’ll come back to this later.) As I’m being favourable it must be said that we’ve seen a variety of stories in terms of style – post-apocalyptic ones, scary ones, humorous ones, and ones of Fantasy, such as the Anita stories, as well as science fiction, all of varying quality and success.

This, however, is Mr. Roberts’ first novel, in the first of three parts. There’s clearly some confidence being shown here, as it takes up nearly 100 pages of the 130-page magazine. As the cover shows us, it is a story of wasps. It begins relatively innocently. Bill Sampson, a cartoonist, has bought a building in the rural village of Brockledean, Wiltshire. He’s very happy working, visiting the local pub and generally getting on with life with his Great Dane Sek.

One day his teenage neighbour Jane Beddoes-Smythe (how British is that name?) wanders in to say “Hello”. They build a platonic relationship whilst Jane is staying in the area for the Summer holidays. During this time there are reports of attacks by wasps, which seem a little far-fetched but really of no consequence. More urgent is the global testing of nuclear weapons currently going on under the seabed.

When our heroes are attacked by a swarm of the afore-mentioned wasps, they soon find that the insects in this case are different to the normal. These are three feet in size, can fly through brick walls and windows, have a sting that can punch through steel plate and mandibles strong enough to decapitate a person. (There are some gruesome descriptions in this story to make that point.)

And if that wasn’t enough, whilst being attacked by the wasps there are earthquakes. The nuclear tests have caused them, destroying Bill’s house. When they eventually escape, they find very few survivors – it seems that whole villages have been destroyed by either the earthquakes or the wasps. Bill and Jane meet an armoured patrol car commanded by Lieutenant Neil Connor, and with Sergeant Ted Willis, the group make a run for the coast. Much of the rest of this part of the story is about their journey towards Weymouth and the challenges they face.

Even if I didn't hate wasps, this story is quite chilling. Whilst my initial impression was that it was going to be in the style of a British Horror B-movie, the story is subtler than that. Roberts sets up a British rural idyll – Sampson living a contented life in the British countryside in a converted public house – and then turns it into something horrendous. Though the added complication of earthquakes happening at the same time as the wasps appearing may be a little too far-fetched, the story is quite shocking in its depiction of the havoc caused by the wasps. Are the wasps a result of the nuclear tests, or are they just taking advantage? It’s not clear (yet.) They are fierce and clever, which leads to some discussion of insect intelligence, which may be as strange as any alien intelligence we ever encounter.

Perhaps the story’s strength is how it visualises the British rural landscape. Roberts has always used descriptions of nature in his work and the Wiltshire setting is nicely done, which makes the impact of this unusual threat all the more jarring. This is a story of 'normal' people trying to survive against adversity.

Despite the appearance of a Granny Thompson-like old lady, in the form of Mrs Sitwell, this is by far Keith Roberts' best work to date. And a great cliffhanger ending. 4 out of 5.

A Distorting Mirror, by R. W. Mackelworth

The second story in two months by Mackelworth, after his story Last Man Home in New Worlds last month. A Distorting Mirror is a story of drug-induced murder in order to climb the occupational career ladder, or at least gain access to housing. The mega-Corporation uses the drugs to determine an employee’s desires, which allows lots of weird-looking goings on and in this case causes the main character to murder his wife when he realises that a) she is competition, and b) he cannot give her what she most desires. All a bit far-fetched for me. 2 out of 5.

The Door, by Alastair Bevan

This one’s a little sneaky, as if you’ve been following closely over the past few months you may have noticed me saying that “Alastair Bevan” is actually…. Keith Roberts!

The ‘Door’ of the title is that which connects the underground Orange City with the world outside. Naylor is attempting to break through it, as it hasn’t been opened for years. A one-point, twist-in-the-tale story about what Naylor discovers once he has broken through. This is a weaker Roberts effort, which makes me think of what an inferior version of The Twilight Zone would be like.

2 out of 5.

The Criminal, by Johnny Byrne

And lastly, a very short story from Mr. Byrne. His return (Johnny was last seen with the very odd Harvest in the January/February 1965 issue) will be greeted with enthusiasm by some readers, although not usually by me, as I find his stories generally too strange for my personal tastes.

However, this very short story is more accessible. A naked man is unceremoniously dumped by a spaceship outside a supermarket. The man explains that this is a punishment because he has been found guilty of a crime. The inevitable twist in the story is who the man says has appeared on Earth as a punishment before him. This short-short story makes its point, then leaves, quickly. 3 out of 5.

Summing up Science Fantasy

And that’s it from Science Fantasy this month – a mere four stories, a bit of a shock after the seven of last month. And two of those are by the same author. But The Furies is shockingly good and may even deserve the generous space given to it this issue.

Let’s go to my second magazine.

The Second Issue At Hand

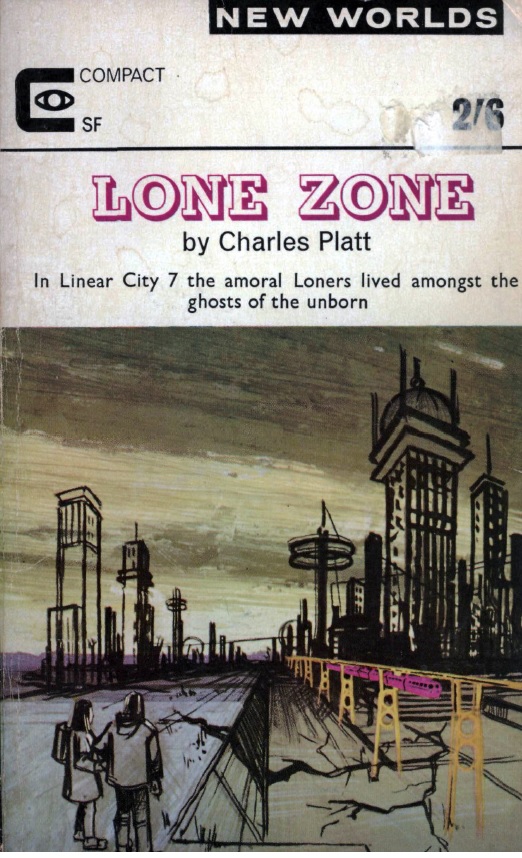

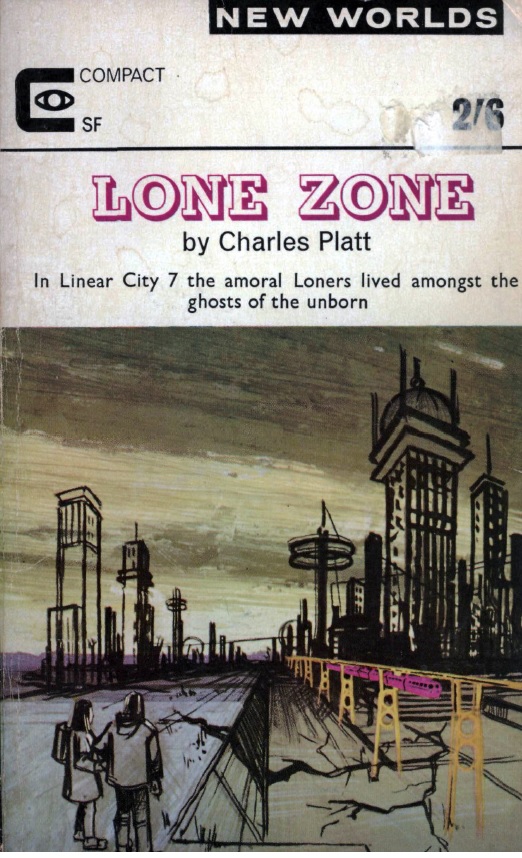

Look! No squares, blur or abstract shapes! This month’s cover, by artist unknown, has a picture you can actually recognise, and it is connected to one of the stories! It still looks pretty basic, admittedly, (compare it with those US covers you get!) but it shows some idea of y'know, relevance. That can only be a good thing, can’t it?

Look! No squares, blur or abstract shapes! This month’s cover, by artist unknown, has a picture you can actually recognise, and it is connected to one of the stories! It still looks pretty basic, admittedly, (compare it with those US covers you get!) but it shows some idea of y'know, relevance. That can only be a good thing, can’t it?

Having tackled the idea of “What is Science Fiction?” last month, Mike Moorcock continues his rhetoric with a debate about whether SF should be about “Space stories” anymore. It has come up in the Letters pages before. Under the title Does Space Still Come Naturally?, Moorcock uses the editorial pages to say that it has but should also make way for the ‘new’ Science Fiction, that of inner space and changing states. He sums it up thus: “Unless a magazine is to become nothing more than a collection of popular engineering articles thinly described as fiction – as has happened to at least one magazine in recent years – then it must look around for something fresh, must encourage something fresh.” I wonder which magazine he is describing? Hmm.

I’m not a gambling person, but after his comments last month, I’m thinking it must be John W. Campbell’s Analog myself. You can, of course, suggest your own.

Both New Worlds and Science Fantasy seem to be putting forward a united front on this idea of the need for fresh new ideas this month. Clearly both Editors feel the eyes of other Editors on them at the moment, and this is them setting out their respective stalls.

Moorcock takes this one step further:

A Moorcock rallying call – I'm not sure I agree with the bold statement he's making, but it is impressive.

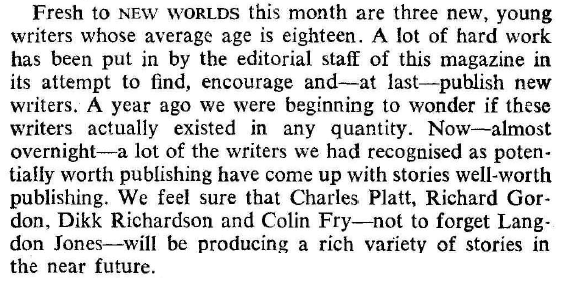

Remember last month when I said that New Worlds seems to be relying on using its well-established repertoire of writers?

Moorcock ends with a not-so-subtle musing: should the magazine expand its size? This is followed by the point that to do so, it would have to raise its price from 2s. 6d to 3s 6d. I await the response in the Letters pages.

To the stories!

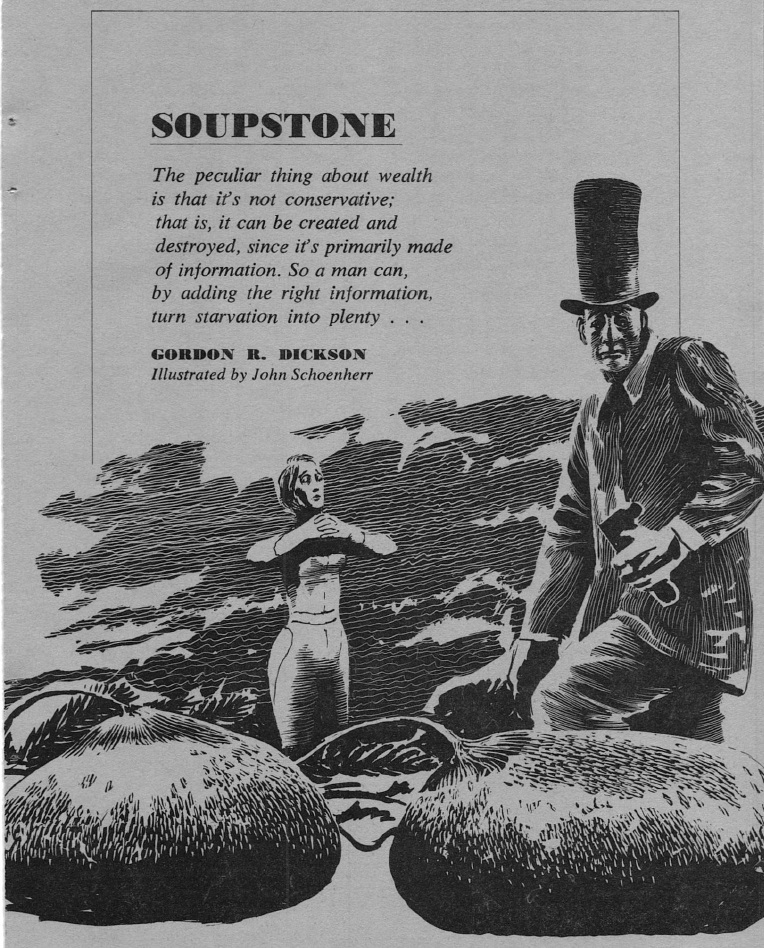

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The Lone Zone, by Charles Platt

After Mr Platt’s amusingly grumpy review of Brian Aldiss’s Earthworks last issue, we now have fiction of his own. It’s a story of inertia and decay that verges on the Ballardian. In the future we have had huge Linear Cities built, but not the population to fill them. Large areas of the cities are now Lone Zones, where abandoned people are left to fend for themselves.

The depressing drabness and sense of decay throughout makes it all feel like a city in a Communist state to me, but the Loners scavenging the buildings for food and everything they need seem like young rebellious types. At the other social extreme, we have Civics, living in an ordered world where everything they do is provided for, organised and programmed.

This story is about what happens when Johnson, a Civic, appears in the Lone Zone of Linear City 7, wanting to live like the Loners and learn about how they live. It’s not an easy choice – the last Civic that did that was hanged in a matter of days. Johnson meets Vincent, the leader of a group of Loners, and tries to tag along with the group.

This is treated with some degree of wariness on the group's part, because other Loners may see them as ‘Civic-Lovers’ and mark them as a target for attack. However, most of the story is about what Johnson discovers about how the Loners live and the deserted decrepit city where they live. It doesn’t end well.

It’s not a bad story, that basically compares the generational differences between the lives of young and old. You could see it as a metaphor story of future free-wheeling hippies versus the staid establishment, if you like. But it is all a bit depressing, and the ending reflects that. 3 out of 5

The Leveller, by Langdon Jones

Illustration by Gilmore

And now it is the Assistant Editor’s turn, with another tale of Inner Space. A man wakes up in a hospital room, aware of his surroundings but is unable to communicate with the world around him. Looking around him, he seems to have left his dying physical body. Whilst watching he finds himself talking to a range of odd creatures – a toad, then a swordsman and then to an ex-lover – in some kind of delusional psychedelic experience just before the body seems to die. The twist in the tale is as predictable as it could be. Again, not bad but nothing particularly revelatory. 2 out of 5.

The Silent Ship, by E. C. Williams

This one has a touch of Quatermass about it. A spaceship returning from Ceres crashes on Earth after no contact is able to be made with the pilot, Grasp. A representative of the firm he is working for is sent to investigate. The pilot is alive but babbling and is taken to hospital. When the ship is studied there is nothing else onboard but some silica rocks.

Tests at the hospital show that Grasp is dying and has no white corpuscles left in his body. The last half of the story shows us what has happened to Grasp. Out on Ceres he has found microscopic life in the rocks. After observing them, Godlike for a while, the ‘fleas’ (as he calls them) invade his body. Grasp is driven by the fleas to return to Earth, where the infection dies upon exposure to Earth’s microbes and kills Grasp. Good old H G Wells!

It’s OK, though I thought the idea of micro-civilizations had gone out with Superman’s Kandor. 3 out of 5.

A Funny Thing Happened, by Dikk Richardson

Oh no. Just the title… this is going to be one of those stories that tries to be funny, isn’t it? A one-page shaggy dog story that involves the Easter Island statues. Awful. 1 out of 5.

A Light in the Sky, by Richard A. Gordon

A debut story which, like a few others recently, channels Edgar Rice Burroughs or Robert E. Howard with Arabian panache before revealing something more science-fictional. It’s OK but I saw the end coming a long time before I read it. 3 out of 5.

Supercity, by Brian W. Aldiss

Ah, now that’s more like it! Good old dependable Brian. (Have I said in the last few minutes that he will be Guest of Honour at next month’s Worldcon in London? No? I am slacking!) Ah – hang on. This is a reprint, a story that was first published in 1957. The third word in the story gave it away to me, being part of the title of an early Aldiss story collection. Just to put that in perspective, 1957 was the year of the first Sputnik. (Yes, that long ago!)

This is an Aldiss story that playfully satirizes societies and plays with language. This even happens with the title, because Brian is at pains from the start to point out that Supercity is not what most readers would expect from the word – a story of Trantorian urbanisation (super-city) – but is instead su-per-city – “the art of becoming indispensable through being thoroughly useless”. It is a story of bureaucracy and how ineptitude can sometimes get you to the top of the pile. Its wryly amusing, fast paced and quite irreverent – just what you need in a Worldcon Guest of Honour!

As good as Supercity is, the issue for me here is that this is not a new story. I suspect the main reason Supercity is here is to remind us what a top-class author Brian is. (Have I said in the last few minutes that he will be Guest of Honour at next month’s Worldcon in London? Really?)

Gloriously ridiculous and yet somehow, for all of its silliness, it has a ring of truth about it. Worth a reprint. 4 out of 5.

The Night of the Gyul, by Colin R Fry

A post-apocalyptic story where some sort of devolved human meets a Boi and a Gyul who wish to travel in a Bote to Frahnts, where lies Paradise.

One of those stories that talks a lot and plays with language in a way that Moorcock seems to love, but actually doesn’t have a lot to say. Once you’ve got your head around what the characters are talking about, there’s not a lot of importance there. I lost interest quite quickly. 2 out of 5.

Book Reviews, Articles and Letters

This month there is one film review and a good few Book Reviews. There is no sign of a Science Article, though – perhaps they have died a death…

For films, Al Good examines Roger Corman’s latest take on "Edgar Allen Poe" (as it says on the back cover), The Tomb of Ligeia before looking at Corman’s work in general. Although The Tomb of Ligeia is not Corman’s best, the Corman versions of Poe’s work are better movies than our British Hammer Horror movies because they stay close to the spirit of Edgar’s writing.

George Collyn comments on Brian Aldiss’s Greybeard (not the best Aldiss has ever written), JG Ballard’s The Terminal Beach (an author in danger of disappearing into himself) and Journey Beyond Tomorrow by Robert Sheckley, which he is much more positive about.

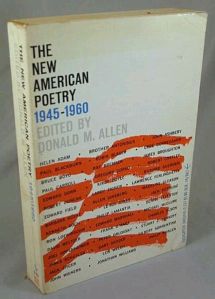

After praising the work of Cordwainer Smith and Kurt Vonnegut, in Collyn’s opinion, Sheckley is seriously underrated, and his work, as well as that of Smith and Vonnegut, reflects the difference in reading material between UK and US readers at the moment. Like Aldiss and Ballard, they are writers prepared to push the boundaries of what we see as science fiction, unlike the majority published in American magazines. Sheckley’s Journey Beyond Tomorrow is “the most important unnoticed event of 1964 as far as SF is concerned.”

James Colvin (aka Mike Moorcock) hands in a more detailed review of The Best SF Stories of James Blish. Taking each story in turn, he eventually puts forward the idea that Blish as an author may be overrated and that other writers such as Cyril Kornbluth and John Brunner deserve to be published as frequently as Blish.

Speaking of Kornbluth and Brunner, Langdon Jones praises their stories in his review of Spectrum IV, edited by Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest. The collection is dissected in some detail as a “good buy” collection, whilst Poul Anderson’s Trader to the Stars is dismissed as a Wild West story set in Space and Robert A Heinlein’s Tunnel in the Sky is a juvenile masquerading as an adult novel, and as such is “readable if slight.”

The Letters pages continue to debate the ongoing issue of what is science fiction, and therefore what should or shouldn’t be included in New Worlds. Suggestions this month include dropping the 'SF' on the cover, and sticking to traditional idioms is too limiting. The debate continues.

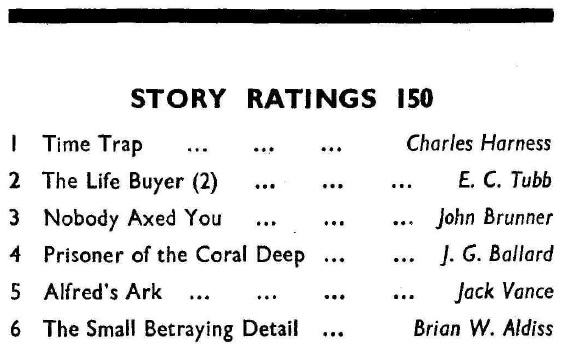

In terms of Ratings, no great surprises for the Star issue from April, other than it is a reprint that gets top billing. Ballard is lower than I expected, but then I thought myself that this was a lesser work. Bearing in mind what George Collyn has said about JG in his reviews this month, does this suggest that the Ballard bubble has burst?

Summing up New Worlds

Another ‘up and down’ issue, with some good and others not so. Moorcock should be praised to trying to nurture new talent, but the results are variable. I enjoyed most the Aldiss reprint, but the issue also gained my lowest rating so far for a story. It’s a good effort but a C+ overall.

Summing up

This month’s issues are difficult to compare as they are so deliberately different. New Worlds has gone for new talent and a range of stories of variable content, whilst Science Fantasy has gambled on one big story dominating the issue, with lesser efforts from Science Fantasy regulars. In the end, the dominance of The Furies means that this month’s best issue for me is Science Fantasy. It’s not perfect, but I think I’ll remember that story for a long time.

And that’s it for this time. Until the next…

Here's those Beatles chaps, celebrating the arrival of Summer with squinting eyes

![]()

![[July 2, 1965] Gallimaufry (August 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IF-cover-1965-08-649x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1965] Every Day has its Dog (July 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650630cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1965] An Hour Of My Life I Will Never Get Back (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Chase [parts 4-6])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/280665homeagain-672x372.jpg)

![[June 26, 1965] Disappointing Duo (June Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650626covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1965] Wasps, Warriors and Aldiss (<i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, July 1965)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650624cover-672x372.jpg)

Look! No squares, blur or abstract shapes! This month’s cover, by artist unknown, has a picture you can actually recognise, and it is connected to one of the stories! It still looks pretty basic, admittedly, (compare it with those US covers you get!) but it shows some idea of y'know, relevance. That can only be a good thing, can’t it?

Look! No squares, blur or abstract shapes! This month’s cover, by artist unknown, has a picture you can actually recognise, and it is connected to one of the stories! It still looks pretty basic, admittedly, (compare it with those US covers you get!) but it shows some idea of y'know, relevance. That can only be a good thing, can’t it?

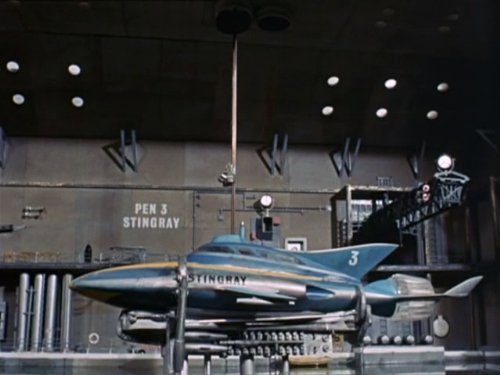

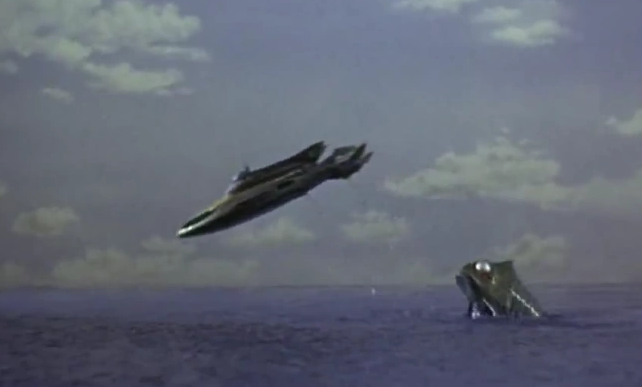

![[June 22, 1965] Standby for Action! (Gerry Anderson’s <i>Stingray</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650622stingray_title-640x372.jpg)

![[June 20, 1965] Ace Quadruple (June Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650620cover-397x372.jpg)

The first story "What Rough Beast?" is the story of a young immigrant named Mike Kronski trying to make his way in America. However, Mike is not the simple East European immigrant he appears to be. He comes from far further afield, from an alternate universe. He also has the ability to bend reality to his will and has accidentally changed his world into ours.

The first story "What Rough Beast?" is the story of a young immigrant named Mike Kronski trying to make his way in America. However, Mike is not the simple East European immigrant he appears to be. He comes from far further afield, from an alternate universe. He also has the ability to bend reality to his will and has accidentally changed his world into ours. "Second Class Citizen" is the story of researcher Charles Craven and the subject of his studies, the dolphin Pete. Craven has taught Pete to understand and speak English, spell simple words and even do chemical experiments. While Craven patronisingly presents Pete to some visitors, we learn from background conversations that there is an international crisis going on. Craven is convinced that this crisis will blow over, like any other crisis before.

"Second Class Citizen" is the story of researcher Charles Craven and the subject of his studies, the dolphin Pete. Craven has taught Pete to understand and speak English, spell simple words and even do chemical experiments. While Craven patronisingly presents Pete to some visitors, we learn from background conversations that there is an international crisis going on. Craven is convinced that this crisis will blow over, like any other crisis before. The novella "Be My Guest" is the story of Kip Morgan, a young man who finds himself possessed by four bickering ghosts after a poisoning attempt gone wrong. Kip also has another problem, he as well as two women of his acquaintance have become invisible to everybody but each other.

The novella "Be My Guest" is the story of Kip Morgan, a young man who finds himself possessed by four bickering ghosts after a poisoning attempt gone wrong. Kip also has another problem, he as well as two women of his acquaintance have become invisible to everybody but each other. "God's Nose" is a short vignette that does exactly what it says on the tin. The unnamed narrator and his female friend debate what the nose of God would look like. Eventually, her lover Godfrey arrives. He has a very prominent nose.

"God's Nose" is a short vignette that does exactly what it says on the tin. The unnamed narrator and his female friend debate what the nose of God would look like. Eventually, her lover Godfrey arrives. He has a very prominent nose. The final story "Catch That Martian" feels very much like a mix between The Rithian Terror and "Be My Guest". Once again, we have a dangerous alien, the titular Martian, who can take on the appearance of any human being. And once again, we have people abruptly taken out of the real world and turned into "ghosts". A young police officer is determined to crack the mystery of the ghosts and catch the Martian in the act. He deduces that the ghosts must have annoyed the Martian somehow, mostly via making noise, and that the Martian has a taste for musical theatre. So the narrator traces the Martian to a Broadway theatre, determined to apprehend him. But before he can give chase, he falls into the orchestra pit, straight onto a bass drum.

The final story "Catch That Martian" feels very much like a mix between The Rithian Terror and "Be My Guest". Once again, we have a dangerous alien, the titular Martian, who can take on the appearance of any human being. And once again, we have people abruptly taken out of the real world and turned into "ghosts". A young police officer is determined to crack the mystery of the ghosts and catch the Martian in the act. He deduces that the ghosts must have annoyed the Martian somehow, mostly via making noise, and that the Martian has a taste for musical theatre. So the narrator traces the Martian to a Broadway theatre, determined to apprehend him. But before he can give chase, he falls into the orchestra pit, straight onto a bass drum.

![[June 18, 1965] Galactic Doppleganger (July 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650618cover-578x372.jpg)

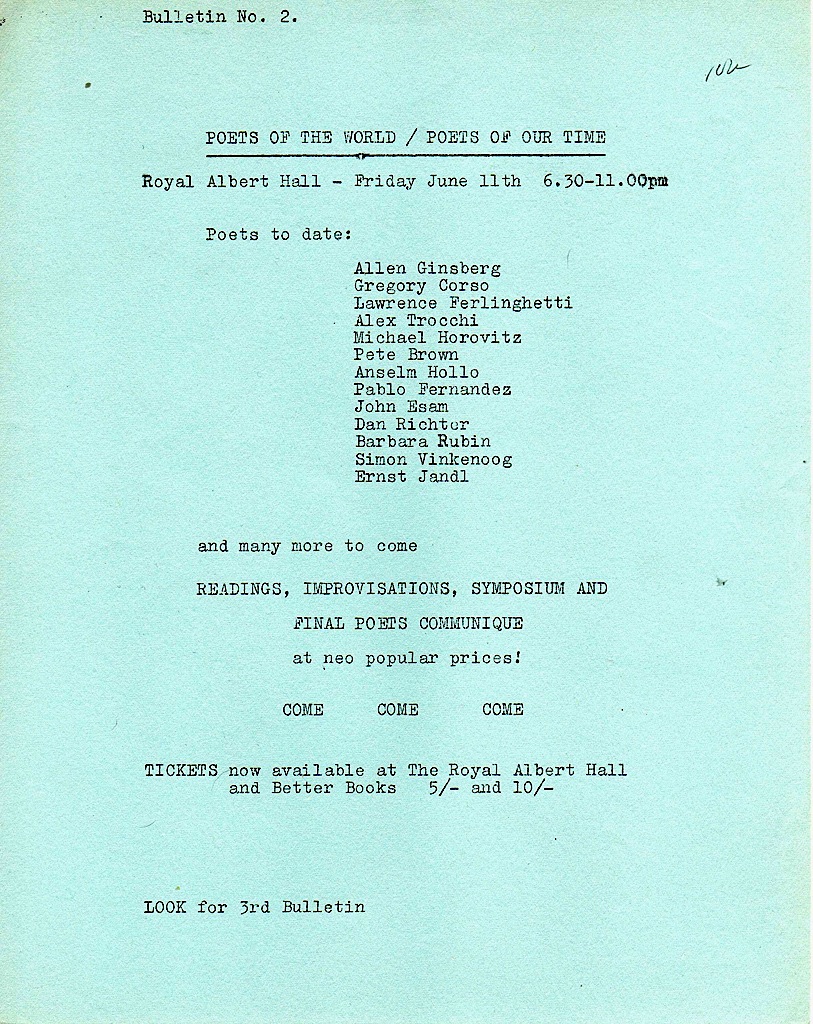

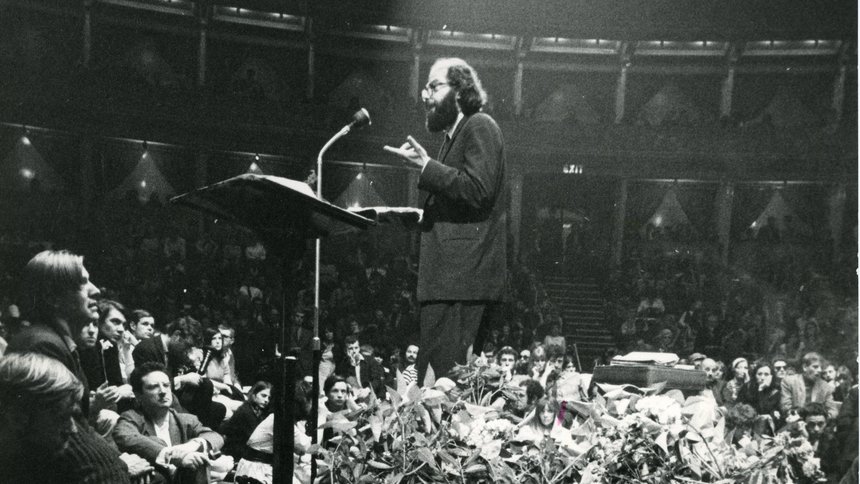

![[June 16, 1965] The International Poetry Incarnation](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Poster-550x372.jpg)

![[June 14, 1965] Our Best Man (the Young Traveler's favorite secret agent)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650614title2-672x372.jpg)