by Gideon Marcus

In the United States, the Fourth of July is perhaps our biggest holiday, celebrating our declaration of independence from our former motherland, Great Britain. It was our escape from taxation without representation, from capricious colonial government, and from forced tea-drinking.

This latest Independence Day saw the premiere of one of the biggest and best summer blockbusters ever made, the appropriately themed The Great Escape. Directed by John Sturges, and starring James Garner, Richard Attenborough, and Steve McQueen, it is the vaguely true-to-life story of a prison break from a Nazi Stalag. Exciting, moving, and beautifully done, it's sure to be a contender for an Oscar or three. Watch it.

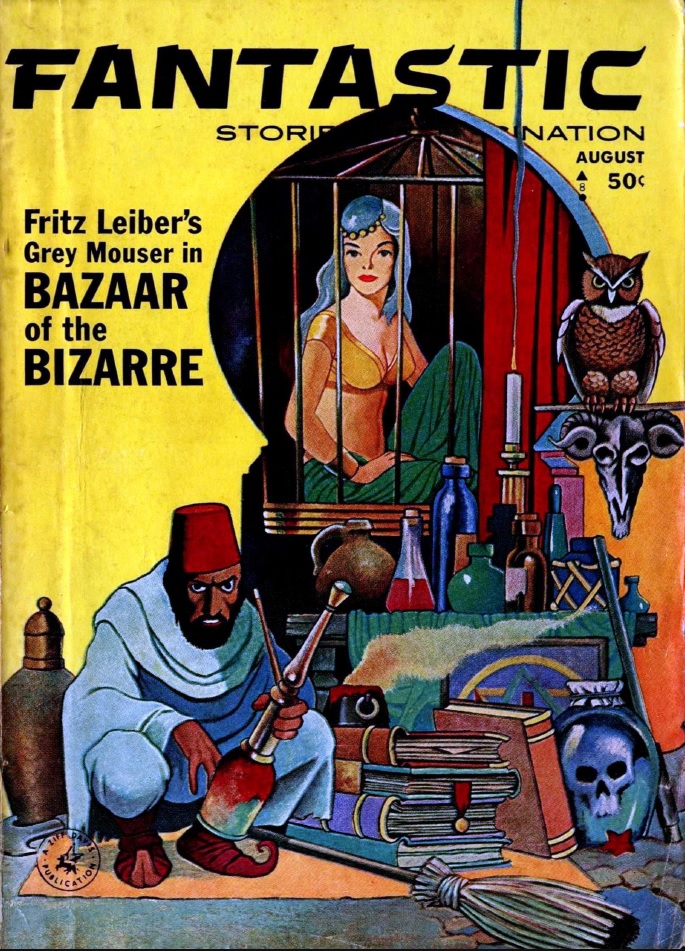

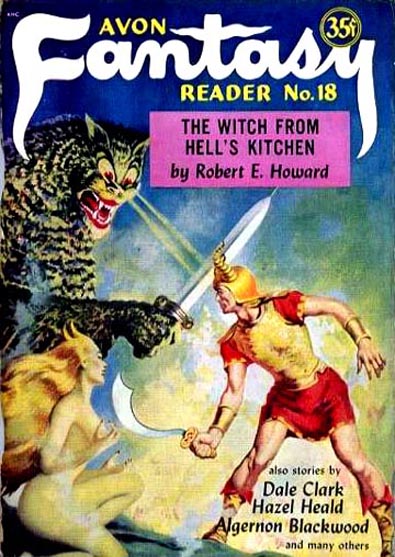

The September 1963 Worlds of IF Science Fiction continues the escape motif. Not just in the normal sense in that it provides an escape from reality, but rather, each of its stories involves an escape of some kind.

Was this a deliberate editorial choice by Fred Pohl or simply a happy circumstance? Either way, it makes for an enjoyable issue that is better than the sum of its parts.

The Expendables, by A. E. van Vogt

Van Vogt, one of space opera's most prominent lights, has been away from the SF scene for fourteen years. So it's quite a scoop for Pohl to have gotten this latest piece, depicting the final stages of a generation ship's journey. A mutiny against the authoritarian captaincy is brewing as the ship nears its destination, and when it turns out the planet intended for colonization is already inhabited, all-out rebellion ensues.

This is a tale that combines two of my favorite topics, first contact and generation ships, and I'm a big fan of Van Vogt. However, I am disappointed to report that Expendables just doesn't hang well together. The science is shaky, the dialogue rather implausible, and the characters a bit too gullible. There is also a queer, slapdash quality to the writing. I suspect this was written in a hurry; a do-over could turn it into a fine story, indeed. Two stars as is.

The Time of Cold, by Mary Carlson

Curt, a spacewrecked man trapped without water on a parched world has little hope of surviving long enough to be rescued. Xen is an amorphous hot-blooded being, native to the planet, desperate for more warmth. Both are menaced by liquid scorpions, beasts who kill in an instant and don't care what world you come from. Are the two aliens the key to each other's survival?

There is an art to telling a story from alternating perspectives such that each scene moves the story forward without repetition. Mary Carlson, a young lady from South Dakota, mastered that art in her first published piece. It's a beautiful, uplifting tale. Bravo. Five stars.

Manners and Customs of the Thrid, by Murray Leinster

In Thrid culture, the Governor can never be wrong, and woe be to one who disputes him. Jorgenson, a representative of the Rim Star Trading Corp., dares to stand up for his native business partner, Ganti, whose wife the Governor would have for his own. Both are exiled for life to a barren rock in the middle of the ocean, escape from which would daunt even the fellows who broke out of Alcatraz.

But, escape they do, and the method is quite ingenious — and logical given the central tenet of Thrid society. Writing-wise, it's a rather workmanlike piece, but the thrilling bits more than compensate. Three stars.

Science on a Shoestring – Or Less , by Theodore Sturgeon

In this month's science column, Sturgeon extols the merits of UNESCO's book, Sourcebook for Science Teaching. I love Ted Sturgeon, don't get me wrong, but sometimes his article topics just don't merit the space they take up. Two stars.

The Reefs of Space (Part 2 of 3), by Jack Williamson, and Frederik Pohl

In the future, Earth is a dystopia under the stifling computerized control of the Machine and its inscrutable Plan. Those who resist the Plan, or for whom the Machine can make no use, are condemned to the Body Bank for reclamation. The last installment, in which state criminal Steve Ryeland was forced by the Machine to develop a reactionless drive, only mentioned the Body Banks in passing. Part 2 deals almost exclusively with them.

In the midst of his work, Ryeland, accused of plotting a wave of disasters around the world, is exiled to Cuba. The tropical paradise has been turned into a kind of leper colony, except limbs and organs are not lost to disease, but instead, according to the demands of the citizens for whom parts are harvested. Over time, the residents lose more and more of themselves until there is not enough to sustain life. One might survive as long as six years, if you can call a limbless, mouthless existence survival. Of course, the tranquilizing drugs they put in the food and water keep you from minding too much…

Fred Pohl already proved he could write compelling horror in A Plague of Pythons. This latest installment of The Reefs of Space would do fine as a stand-alone story (and I have to wonder if it was originally intended as such). The tale of Ryeland's attempt to escape an escape-proof prison is gripping, even if the trappings of the greater story aren't so much. Four stars.

The Course of Logic, by Lester del Rey

A mated pair of parasitic aliens, who use other creatures as their hosts, have been trapped on a bleak world for eons. Their home galaxy has been destroyed, and the only compatible beasts they've found lack the fine motor skills to construct spaceships for escape — or any other kind of technology. So they are delighted when they come across a pair of humans, for our form is absolutely perfect for their needs. Will these puppet masters, once ensconced in our guise, escape their planetary prison and become unstoppable conquerors?

Lester has been too long from our ranks, but it looks like he's back to stay, given his recent record of publication. This is a grim piece but with a splendid sting in its tail. I also particularly enjoyed this bit of evolutionary teleology, said by the dominant female to her mate:

"The larger, stronger and more intelligent form is always female. How else could it care for its young? It needs ability for a whole family, while the male needs only enough for itself. The laws of evolution are logical or we wouldn't have evolved at all."

And before you scoff, recall the hyenas and the bees. Four stars.

The Customs Lounge, by E. A. Proulx

This vignette appears to be a Tale from the White Hart, but it's really a story of human cleverness under alien domination. It is apparently the first piece by Proulx, "a folk singing star-gazing man from upstate New York," and while it's nothing special, it's also not bad. Three stars.

Threlkeld's Daughter, by James Bell

Last up, we have a tale not of escape, but of entrapment. A six-legged, tailed tree-creature from Alpha Centauri takes on comely human female form and travels to Earth to secure a male homo sapiens specimen for study. But with the human body comes human hormones and emotions, and love creates its own entrapments.

It's a cute little piece, more like something I'd find in F&SF. Three stars.

Thus ends a fine issue of an improving magazine. If you ever find yourself imprisoned, in gaol real or virtual, one of these stories might give you the inspiration to break out. Or, at the very least, make a few hours of your sentence more pleasant.