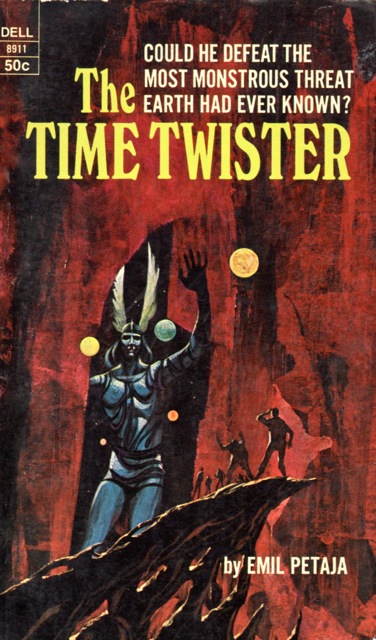

by Victoria Silverwolf

Emil Petaja is an American writer of Finnish ancestry. His best known works are a series of novels based on the Finnish national epic the Kalevala. (Saga of Lost Earths, The Star Mill, The Stolen Sun, and Tramontane. These were all published from 1966 to 1967.)

Petaja's latest novel, although not part of this series, also deals with themes from Finnish mythology.

Cover art by Jack Gaughan.

Doctor Stephen McCord is an anthropologist. Although he's the only major character who isn't of Finnish descent, he's studied the culture and knows something of the language.

Before the novel begins, his college buddy Art Mackey took off for a remote area of Montana, in search of his girlfriend Ilma, who mysteriously returned to her old homestead. Stephen gets a tape recording from his friend, giving him a few hints as to what's going on. (It also serves as exposition for the reader.)

It seems that the former logging town of Hellmouth, inhabited by Finnish immigrants, was completely destroyed in a huge forest fire in 1906. When Art arrived in search of Ilma's nearby farmhouse, he found the place looking exactly the way it did six decades ago, with some of the former citizens still alive and kicking.

Intrigued by this mystery (and wondering if his pal has gone nuts), Stephen makes his way to the supposedly vanished town. He discovers that Hellmouth is indeed still around. Furthermore, the inhabitants worship Ukko, the chief god of Finnish legend. (Roughly comparable to Zeus or Thor, I believe.)

Stephen finds Art, and they both search for Ilma. Things get weird when they actually run into what seems to be Ukko, a being whose presence is so overwhelming that it's almost impossible not to fall to one's knees in adoration. The apparent god promises to make Earth a utopia, in exchange for worship. Ukko also has plans for Stephen.

What happens involves Ilma's elderly father Izza, her hunchbacked brother Yalmar, the local schoolteacher/librarian, and the steel plate inside Stephen's head, a souvenir of his time as an ambulance driver during a conflict in Southeast Asia. (Maybe Vietnam, as the story takes place just a little bit in the future, some time in the 1970's.)

The author writes clearly and elegantly. I always knew what was going on and was able to keep track of the characters. There are many vivid descriptions of Petaja's home state of Montana. (He now lives in San Francisco, which is also depicted excellently in the early part of the book.)

Besides having a compelling plot that kept me reading in one sitting, the novel has some intriguing and controversial things to say about the nature of deity and its relationship with humanity. Even at the very end of the text, Stephen still isn't sure if opposing Ukko was the right thing to do.

Four stars.

Comedy and Tragedy

The latest Ace Double to fall into my hands (designated as H-85, for those of you keeping score) offers a pair of short novels with contrasting moods. One is lighthearted, the other is serious. Let's start with the humorous one.

Destination: Saturn, by David Grinnell and Lin Carter

Cover art by Kelly Freas.

David Grinnell is actually the well-known fan, writer, and editor Donald A. Wollheim. He also created the Ace Double series, so he must feel right at home.

This novel was published last year in hardcover.

Cover art by Michael M. Peters.

The protagonist is a filthy rich and rather egotistical fellow named Ajax Calkins. A little research reveals that Wollheim (without co-author Carter) has been writing about him since 1941, sometimes under the pen name Martin Pearson. Most recently, this old material was recycled into the novel Destiny's Orbit. The Noble Editor gave it a lukewarm review a while back, calling it a juvenile space opera.

In the current volume, Ajax is the king of an asteroid that is actually a gigantic spaceship built by the civilization that was destroyed when their home planet blew up long ago, creating the asteroid belt. He and his fiancée Emily Hackenschmidt are on Earth, leaving the asteroid in the hands (so to speak) of their loyal Martian friend, a spider-like being called Wuj.

Dastardly amoeba-like aliens, the inhabitants of Saturn, are the sworn enemies of Earth. (In a touch of satire, we find out that they were perfectly nice folks until they learned aggression from humans.) Two of the Saturnians disguise themselves as Ajax and Emily and convince Wuj they're the real thing. They set off for Saturn, eager to uncover the ancient spaceship's secrets and use its advanced technology to conquer the solar system.

What I've failed to convey is the fact that this is a comedy. Ajax manages to save the day, of course, but he's also something of a fool. The more levelheaded Emily is often exasperated at him, with good reason.

The novel is written in a dryly tongue-in-cheek style that is more amusing than the usual science fiction farce. There are quite a few witty lines. I'm not a big fan of comic SF, but this one is better than some.

Three stars.

Invader on My Back, by Philip E. High

Let's flip the book over and take a look at something without laughs.

Cover art by Jack Gaughan.

The cover proudly announces that this is the novel's first book publication. I assume that's true, but there's also a British hardcover edition that came out this year.

Cover art by Colin Andrews.

The story takes place a few hundred years after society fell apart, for reasons not apparent until later in the novel. Humanity has managed to build itself back up, but there's been a strange change in people. They're divided up into castes. Again, the explanation for this is unknown.

Roughly half of the population consists of Norms; ordinary folks. The other half are Delinks; murderers and other violent criminals. Some Norms and Delinks are also Scuttlers. These are people who have an intense phobia about the sky, and can't bear to look at it.

A small number of folks are Stinkers. Everybody else hates these people; so much so, that few of them survive. Those who do isolate themselves and protect their lives with various resources.

Michael Craig is a Stinker. (That looks like an example of nasty graffiti, doesn't it?) He gets a message from the police (by mail; if he came anywhere near them they would try to kill him) asking him to try an experiment. The cops want to know what would happen if two Stinkers met. Would they loathe each other on sight?

Michael agrees to meet Geo Hastings, a Stinker who lives in Africa. The oddly named Geo turns out to be an attractive woman. If you think the two are going to fall in love, give yourself an A in predicting familiar plot developments.

Besides not trying to kill each other, the two discover that they can communicate telepathically. Things would seem to be turning out nicely, if it were not for the Geeks.

A Geek is a type of human being that has just appeared recently. They are physically superior, tend to be cold-bloodedly calculating, and are intent on wiping out the rest of humanity. In particular, they are bent on destroying the Stinkers; not for the usual reason (pure, unexplained hatred) but as part of their plan to conquer the world.

Without giving anything away (although you may be able to predict the novel's plot twists), let's just say the reason for all these weird happenings is revealed. Can Norms, Delinks, and Stinkers work together against the Geeks and the secret menace behind them? Not to mention the Scuttlers, who have a vital role to play.

This isn't a bad novel. Not great, but not bad. The story held my interest. (I haven't mentioned Michael's three heavily armed robot birds, who are the most charming characters.) It's worth reading once.

Three stars.

by Cora Buhlert

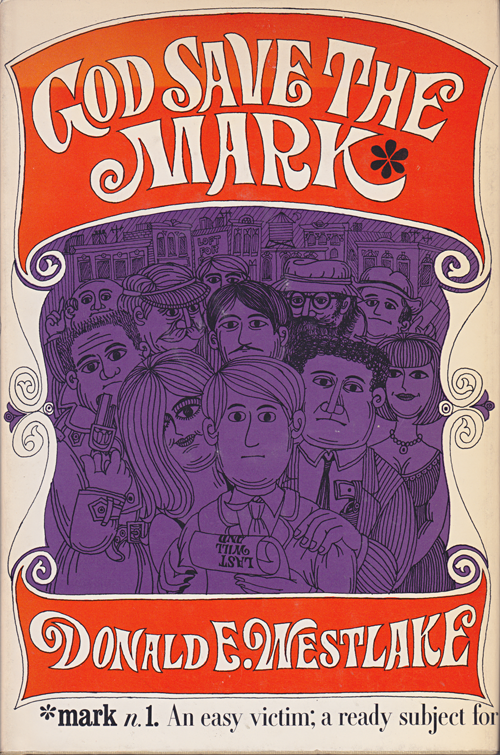

The Long Con: God Save the Mark by Donald E. Westlake

Science fiction may be my first love, but I read other genres as well. And so my latest pick-up at the local import bookstore was a crime novel entitled God Save the Mark by Donald E. Westlake. The reason I bought the book is that it just won the prestigious Edgar Award, i.e. the mystery genre's equivalent to the Hugo and Nebula Awards, for the best crime novel of the year, beating out Rosemary's Baby by Ira Levin. Any novel that can beat a juggernaut like Rosemary's Baby is certainly worth checking out, so I picked it up. And reader, I was not disappointed.

The Most Gullible Man in New York City

The protagonist of God Save the Mark is one Fred Fitch, who must be the most gullible man in New York City. Fred is a magnet for con artists and there's not a scam in existence that Fred will not fall for.

The novel opens with Fred getting a phone call from a lawyer that his Uncle Matt has died and left Fred more than three hundred thousand US-dollars. This makes even the extremely gullible Fred suspicious, especially since he does not have an Uncle Matt.

So Fred alerts his friend his best and probably only friend, Detective Jack Reilly of the NYPD's "bunco squad", i.e. the police department dealing with fraud. Reilly tells Fred to go to the appointment with the fake lawyer, so Reilly can arrest him red-handed. Alas, Fred is late for the meeting because he got scammed… again and it turns out that the lawyer is not a fraud after all, but the real deal. As is the will of the late Uncle Matt. Fred really did inherit more than three hundred thousand US-dollars.

However, there's a catch or rather several. For starters, Uncle Matt was a con artist himself and the black sheep of the family, which is why Fred has never heard of him. What is more, Uncle Matt, though terminally ill, was murdered. Which makes Fred the prime suspect.

A City of Con Artists

The situation quickly escalates. To begin with, Fred's new found riches make him a target for even more would-be con artists, including a childhood sweetheart who intends to hold him to a marriage proposal made as a kid or sue him for breach of promise and a neighbour who wants to publish his alternate history novel Veni, Vidi, Vici with Air Power via a predatory vanity press. Worse, whoever murdered Uncle Matt is now taking potshots at Fred. Finally, Fred also finds himself entangled with two very different women, Gertie Divine, a former stripper who was the late Uncle Matt's nurse, and Karen Smith, Reilly's bit on the side who still hopes he'll marry her someday, once he gets over his Catholic guilt induced reluctance to divorce his wife.

The intense pressure under which Fred finds himself finally makes him wise up. He tells off several would-be con artists and also puts his skills as an independent researcher to use to investigate Uncle Matt's murder himself, since he no longer trusts the police.

However, there are still many twists and turns ahead, including a hilarious chase scene where Fred steals a child's bicycle to escape his pursuers and ends up tumbling headfirst into a pond in Central Park.

This was the first novel by Donald E. Westlake (who also writes as Richard Stark and under a number of other pen names and has even dabbled in science fiction on occasion) that I read, but it certainly won't be the last, because this book is laugh out loud funny and a complete and utter delight.

In many ways, God Save the Mark is a reminiscent of the screwball comedies of thirty years ago, yet it is also a solid mystery that plays fair with the reader and delivers plenty of red herrings as well as all the clues needed to solve it. The novel also offers an excellent overview of the various cons and scams going around, some I was aware of and others that were completely new to me. The ending is a perfect fit.

A Deserving Winner?

So is this novel better than Rosemary's Baby? Well, the two books are difficult to compare, because they are so very different. But all in all, I'd agree with the verdict of the Mystery Writers of America that God Save the Mark is a most deserving winner of the 1968 Edgar Award.

A fluffy, frothy caper that will leave you rolling on the floor laughing and guessing till the end.

Five stars.

by Jason Sacks

Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner

Sometimes as a reviewer you just don’t quite trust yourself when you encounter something totally unexpected. When you read a work which feels sui generis for science fiction, a book which draws comparison to literary fiction like Dos Passos, Burges and Nabokov, it’s hard to assess that book in its own context.

John Brunner’s fascinating new novel Stand on Zanzibar is the spiritual successor to those modernist writers.

Brunner’s novel reads as part pulp fiction and part assault-the-senses bursts of information. Zanzibar is a prophecy and a critique, a satire and a work of deep seriousness. It has plot lines and complex emotions and an energy that won’t quit, and at 576 pages of very short chapters, it somehow felt exhausting and left me craving more. It’s also extremely hard to describe, so be aware I’m barely skimming the surface here, and I welcome anybody who’s willing to add their own comments in an LoC to this magazine.

Let’s start with the easy parts to describe. On its most basic level, Stand on Zanzibar is about the problem of overpopulation. When we all were in diapers, if stood side by side, all of humanity could take up a space roughly the size of the Isle of Wight. By the distant year of 2010, however, as Brunner writes, "If you allow for every codder and shiggy and appleofmyeye a space of one foot by two, you could stand us all on the 640 square mile surface of the island of Zanzibar."

There’s so much information contained in one sentence. You get one of the key themes of the novel and also a feeling of Brunner’s approach to his writing. Like Burgess’s punks in Clockwork Orange, the characters in this book chatter and mumble in an invented slang which feels clever and becomes part of the larger reading experience of the book. (Brunner admits a strong influence on him from Burgess.) The language forces readers out of our comfort zones and therefore pay closer attention to the often fractured way Brunner chooses to tell his tale. (A codder is a certain type of man and a shiggy a certain type of woman and an appleofmyeye is a child, by the way.)

The other key piece of information in that sentence above how fears of world overpopulation has led to strong laws against procreation. Those restrictive rules in turn have created a vast black market in child-rearing, as citizens are shown considering traveling to the state of Puerto Rico to have kids, much as one might escape their home state for an abortion or divorce to defy difficult local laws. World society also angles towards eugenics, forced sterilizations and genetic modifications. Can suicide booths be far behind?

All of the above is mere background – though thoughtful, fascinating background – for the main thrust of this sprawling exercise. Much of the book tells the story of the small calm African country of Beninia, population 900,000, which has become the main staging point for refugees from wars in three neighboring countries. Those refugees despise each other, but the country has a kind of tenuous peace under the benevolent rule of President Zadkiel F. Obomi. However, President Obomi wants to retire. And when he retires, what will happen to the peace he worked so hard to broker?

Enter another key aspect of this book’s fascinating plot. Obomi is good friends with American Ambassador Elihu Masters, and as they discuss the problem, Masters comes up with an unexpected suggestion: what if American corporation General Technics (motto: "The difficult we did yesterday. The impossible we're doing right now") took over the country? What if the country exchanged its vast offshore mineral and oil reserves for education and infrastructure creation?

Parts of the book alternate between reveries by Obomi and the life in New York City shared by roommates Donald Hogan and Norman House. House is “Afram”, African-American, and has astutely used his race and his native intelligence to gain himself a powerful role inside GT. That means he will be on the ground while GT moves operations to Beninia – that is, of course, if Norman can shake his deep feelings of melancholia and dissatisfaction with his life and his career. Hogan, meanwhile, seems innocent since he spends most of his days at the New York Public Library. But in fact Hogan is a “Dilettanti”, a spy recruited by the government because of his preternatural skills at discovering patterns in seemingly normal experiences. Hogan is passive until “activated” by the government, and he worries about that aspect of his life.

Until he actually is activated and sent to Socialist Asian country of Yatakang, where the government has announced how eminent geneticist Dr. Sugaiguntung has invented a way for everybody around the world to give birth to perfect children. But is their assertion true, or it just a lie on top of all the other lies circulating in this complex world? Can Donald prove the Yatakang government’s announcement is a lie? Can he persuade the people of Yatakang to support the leader of a guerilla rebellion which is happening in the country’s mountains?

*Whew.* There’s so much there just in the plot. I’m sure you can see the pulpy outlines of a Le Carre style spy novel, as well as chances for Swiftian social satire in both storylines I’ve described, and yet all that description barely scratches the surface of this most profoundly wild novel. Because underpinning this entire book is a deeper critique of world society, a society full of selfishness and cheap thrills and tawdry media which creates false reality in its shows.

Most damningly, Brunner presents a world in which people seem constantly interconnected and yet somehow deeply distant from each other. Hogan and House, for instance, despite being roommates, scarcely know anything about each other. The media consumed by the people in this world prevents them from being social, and that gap has vast societal consequences. When people can literally project fictionalized versions of themselves on fantasy television shows, what attraction does the real world have? Drugs are all pervasive. Suburbs are collapsing. The planet is groaning from the weight of all the people living upon it. Yet the vast majority of men and women in this world care much more about the shows they consume than they do about the world they have created.

And there’s so much more here. There’s Shalmaneser, the super computer which makes critical decisions on Earth (wonder if Brunner heard about Clarke and Kubrick’s 2001 ideas?). There’s the muckers, a group of random people who go on killing sprees for no reason. There’s a drug which forces people to tell the truth which is given to a bishop who spends a Sunday mass telling everyone his real feelings about God. I could go on and on, and dear reader, I know I’m skipping one of your favorite elements of this book.

But I grow filled with a bit of despair that I could do an adequate job of explaining any element of this book; even more, I despair at the idea a mere plot summary would be useful to anybody who might be considering reading this astounding book.

So let me sum my feelings up this way. Like many of us here at the Journey, I’ve long been a fan of Mr. Brunner’s writing. But Stand on Zanzibar takes all of John Brunner’s writing abilities and takes them to a quantum level. He displayed massive potential in many of his earlier works, but here Brunner shows that potential paid off in spades.

No matter the context, on first read, Stand on Zanzibar Brunner has delivered the wildest, weirdest, most successful book of the year so far. Previously I called Alexei Panshin’s Rite of Passage the best book I had read in 1968 up to that point. Brunner’s achievement far exceeds Panshin's. I hope to be rereading this book in that far-flung future of 2010 and seeing how many of Brunner’s prophecies came true.

Five stars.

[And new to the Galactoscope, we are pleased to introduce poet and author Tonya R. Moore, who has dived into New Wave's deep end with her first brush with Chip Delany….]

by Tonya R. Moore

Nova, by Samuel R. Delany

Nova was my first encounter with the work of Samuel R. Delaney who has, thus far, proven himself exemplary of the originality and innovativeness one would expect from the current New Wave of Science Fiction writers. Set in a distant future where humans have migrated to other worlds, this book paints a chaotic but beautiful picture of human turmoil and adventurousness in an ever expanding universe.

Lorq Von Ray is a born upstart from a family of nouveau-riche propelled into high society by their ill-gotten gains. He makes friends and, eventually, enemies with Prince and Ruby, quintessential Earth-nobility driven by power, greed, and a keen sense of self-entitlement.

Von Ray grew up haunted by constant reminders of the social stratum wedging a vast chasm between himself and the siblings. Ever ambitious, Von Ray pits wills and wits against Prince and Ruby, aiming to upset the economic balance of power between the Draco and Pleiades systems.

Further embittered by their twisted and broken friendship, he sets out, with dogged determination, to hit the motherlode of interstellar treasures in the form of illyrion, the ephemeral byproduct of a nova and the most valuable and potent energy source known to mankind.

Should Von Ray succeed in this second attempt to capture this precious material in abundance from the nova, his payload promises to transform the economy of the Pleiades system and upend Prince’s monopoly on interstellar travel technology which allows them to hoard most of the wealth and stratify the balance of power between the Draco and Pleiades systems.

This book introduces a motley cast of characters who are destined to be enmeshed in the many dangers and high drama that comes along with being employed by Von Ray.

Mouse, for example, is a nomadic troubadour eking out a meager living while playing interplanetary hopscotch in the Draco system. He winds up on Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, while seeking employment on one of the spaceships bound for other star systems and greater opportunities.

Here, Mouse encounters Lorq Von Ray, scion of the richest family in the Pleiades system and jumps at the opportunity to join the ragtag crew of cyborg studs on Von Ray’s spaceship bound for the heart of an exploding star.

Ruby Red and Prince don’t appreciate Von Ray’s intent to rise above a station they consider beneath them, not to mention shift humanity’s prosperity from Draco to the Pleiades system. A cargo hold filled with seven tons of illyrion would certainly help him achieve that.

Mouse and his syrynx, a musical instrument that conjures holographic imagery, bear witness to the changing times while the melodrama of a twisted love triangle unfolds among Von Ray, the selectively diffident Ruby Red, and the pridefully neurotic Prince.

The gypsy troubadour playing his syrynx is a recurring motif representing the backdrop humanity's culture and history against which the story unfolds. The syrynx, a stolen object, ironically foreshadows the climax of the story where it is once again stolen then turned into a weapon.

Delany’s command of astrophysics and the science behind supernovas is reasonably solid. He proves himself a master of using literary language to describe scientific concepts and the murky dynamics of human interpersonal entanglements but there are elements of Nova that make little sense.

Ruby Red’s complicity with Prince’s cruelty and neurotic behavior seems arbitrary, for instance. As a character, she seems to lack a will of her own. Despite her prominence in the story, we’re never given a real glimpse inside the mind of the woman. What does Ruby Red want? Why does she do the things that she does?

Ultimately, Nova is a beautifully chaotic and original tale rife with vivid, sometimes visceral prose, exuberant dialogue, and an intriguingly colorful cast of characters.

4.5 stars.

"Stand on Zanzibar" is extraordinary, far better than anything else Brunner (who can be quite good) has ever produced. In contrast, it's no surprise that "Nova" is so good, given Delany's previous work.

Welcome to the review crew, Tonya! Great review of Nova. Delany has been on my reading list for a while now, and it’s good to hear he’s kept up the levels of quality he showed with Babel-17.

1968 appears to be shaping up for a great year for the major awards.

Zanzibar is remarkably good; I loved it. Really made me feel like I was living in the horribly crowded year of 2010.