by Gideon Marcus

High Hopes

In preparation for the last episode of The Journey Show, in which we discussed the movies of the last fifteen years, the Young Traveler and I cast about for every SF movie we could find that we'd missed the first time through. That's how we came across the "They came from 1951" double feature that Lorelei wrote so engagingly about.

And it's how we ended up in a dingy second-run theater at the edge of town for a viewing of the 1956 hit, Forbidden Planet. I'd heard a lot about the film, that it was the first big budget rendition of classic space opera, that it was absolutely gorgeous, and that I was somehow remiss as a reviewer of science fiction for not having seen it.

So don't let it be said that my upcoming savaging of the film is the result of any predisposition to be negative. Indeed, I had every expectation that Forbidden Planet was going to be something special.

And, in some very negative ways, it is…

The Reality

Things start encouragingly enough, opening on a shot of the United Planets cruiser "C-57D" zooming through space. All of the space ships of the 1950s (with the exception of the novel manta-ray looking ships from War of the Worlds) fall into two categories: V-2 rocketships and flying saucers, and the C-57D is a classic example of the second type.

The vessel, skippered by Commander John J. Adams (Leslie Nielsen), has traveled more than a year to the real-life white star, Altair, to check up on the Bellerophon, a ship last heard from two decades before. C-57D is apparently traveling at superluminal speeds, and in a nice bit, all of the crew head into cylindrical stasis chambers for the transition to normal space.

Eight minutes into the movie, Lorelei and I were hooked. This picture was absolutely beautiful and unlike anything we'd seen before. We licked our lips in anticipation.

And then the disappointments began.

After making orbit around the green-tinged Altair IV (orbiting a strangely orange Altair) the C-57D gets a call from the surface. Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) of the Bellerophon is the sole survivor of the prior expedition, and he tells Commander Adams in no uncertain terms that he needs no assistance and, in fact, the relief ship will be in danger if it lands. Rather than asking why he shouldn't proceed, Commander Adams instead cuts off Dr. Morbius in mid-admonition!

"This program is boring – let's tune to Jack Benny!"

Nevertheless, the movie soon seduces us again with the following amazing shot and a vibrant set of electronic sound effects.

Upon landing, they are met by "Robby the Robot," a character the filmmakers were so proud of that they gave him his own title card. It's true that he moves with all the grace of a man in a lumpy suit, and I have the disadvantage of having seen him reused in at least one episode of The Twilight Zone, but a robot that doesn't look like a person is a pleasant surprise.

Despite Dr. Morbius' earlier protestations, Robby has been sent to invite the Commander over for tea. Adams and two of his men (the crew of the C-57D is entirely male, natch), Lieutenant Jerry Farman (Jack Kelly) and "Doc" Ostrow (the TV ubiquitous Warren Stevens) head over. It turns out that Dr. Morbius has made quite a nest for himself.

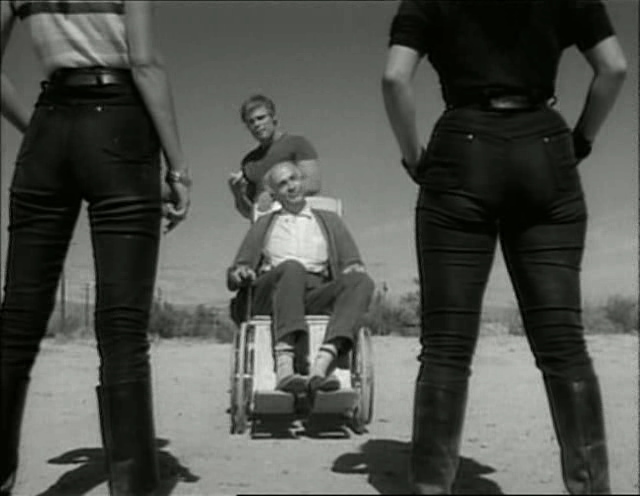

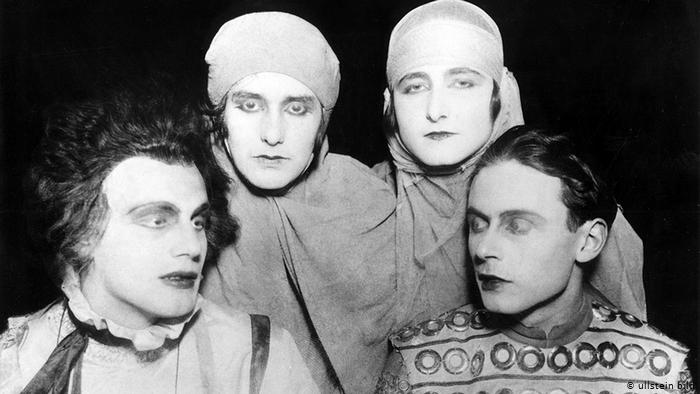

Dr. Morbius in a typically declamatory pose

Dr. Morbius is affable enough, but he has a somber tale, which he delivers in a rather toneless monologue, as if telling a bedtime story. Shortly after landing, the crew of the Bellerophon suffered gruesome death after death at the hands of some unseen beast. Only the doctor and his wife were spared, because they loved the planet rather than fearing it, the doctor believes.

Sadly, his wife died soon after the incident due to natural causes. Nevertheless, Dr. Morbius has not been alone the whole time. For one, there's Robby: his home-built robot is the ultimate servant, able to produce any item from its belly…and it also does dishes!

And then, there is Altaira.

This fetching thing (Anne Francis, currently Honey West) is, of course, the daughter of Dr. Morbius and his wife, the latter having died in childbirth. She is excited at meeting men, particularly the Lieutenant and the Commander (no accounting for taste – Doc Ostrow is the most likeable of the characters even if he's the first one to throw out a sexist comment, that Robby will be the bane of housewives everywhere).

Lieutenant Freeman wastes no time with the coquettish Altaira, first denigrating his Commander in a way that would be mutinous if Adams knew, and then explaining that kissing is beneficial to Altaira's health and they should indulge in it right quick. It's a scene with all the charm of Walter Breen describing his virtues to your son.

Altaira does not derive any pleasure from the event, and thankfully, Commander Adams shows up then to break things up. But don't breathe a sigh of relief too quickly. He's just there to tell Altaira that it's all her fault he assaulted her, and that she needs to put some damned clothes on, for goodness' sake. After all, who is he to impose a modicum of discipline and respectfulness over his crew? The skipper?

It gets worse, as he browbeats her for being flirtatious, clearly resentful that he wasn't the first target of her attentions. Finally, he sends her off, all but threatening to spank her.

(It's in this scene, by the way, that we learn that the ship's complement of the C-57D is 18. There is absolutely no way that 18 men were on this tiny saucer for more than a year.)

That night, something invisible sneaks past the sentries and destroys vital components of the spaceship. The vessel is marooned unless repairs can be made. Despite knowing that there is an invisible terror on the planet, Commander Adams is furious with his guards, roaring at them and meting out severe punishment. At this point, we were wondering if the movie was deliberately showing that Commander Adams was both incompetent and a jerk in a subversion of the hero type. Of course, we were giving the film too much credit.

This painful vignette is followed by a truly groanworthy stretch of dialogue between Adams and Chief Engineer Quinn:

Quinn: Half of this gear we can replace and the rest we can patch up somehow…except this special Klystron frequency modulator. With every facility of the ship, I think I might be able to rebuild it…but frankly, the book says no. It came packed in liquid boron in a suspended grav…

Adams: All right, so it's impossible. How long will it take?

Quinn: Well, if I don't stop for breakfast…

Adams: Get on it, Quinn.

Quinn: Thank you, sir.

This bothered me. If the thing is fixable, give an accurate estimate, don't be coy to burnish your credentials as a miracle worker. Frankly, this also made me think less of the Commander, who let him go without a actual timetable.

Note: I tend to be particularly sensitive to problematic portrayals of people in charge. As a person who has run companies and other entities for years, the leader types are the ones I most identify with, and they have the job I have most familiarity with doing. When I see it done wrong, especially when we're supposed to admire the leader character, it drives me nuts.

On with the show.

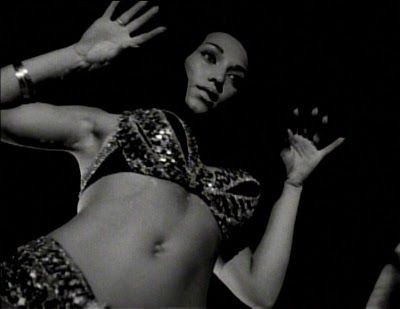

Commander Adams, having sated his sadism quota for the day, heads out with Ostrow back to Dr. Morbius' pad to get more information about the phantom beasts of Altair IV. There, they espy Altaira bathing in the nude, after which she comes out of the water and puts on a new dress that covers everything, per Adams' prior orders. You see, when Adams chastised her for being a floozy, she really liked it. And in short order, this is happening:

At this point, Lorelei asked me why I was such a horrible father subjecting her to this dreck. She clearly has a poor memory – subjecting her to dreck is a tradition that goes back almost seven years now. In this case, though, my pain was easily as acute as hers. And before you rejoinder my objection with, "Well, Altaira's clearly enjoying herself, so what's the problem?" I'll point out that Altaira isn't a person. She's a flat character portraying what is obviously wish fulfillment on the part of the writer; she bears no resemblance to an actual human being in this situation. That's why it's so painful to watch – she's treated horribly and then reacts unnaturally.

The smooching between Altaira and Adams enrages the girl's pet tiger, and Adams zaps the kitty into nonexistence. Which just underlines another ridiculous part of this movie. At every possible juncture, Adams whips out his gun. He's already done it (I think) three times before this point in the movie. It's a miracle the tiger is the first casualty of his itchy trigger finger.

When Dr. Morbius is not immediately forthcoming, Adams and Ostrow break into his private office and start reviewing the doctor's papers. Morbius catches them in the act and is rightfully upset.

However, he calms down quickly enough and embarks on another monologue about how Altair IV used to be inhabited by a poweful species called the Krell, how the race had built these giant machines powered by the heat of the planet itself, and how, one day, they all murdered each other.

While the delivery is again unremarkable, the subject matter is interesting, and the scenes from the guided tour of the alien equipment is breathtaking, visually and aurally.

It turns out that the doctor is something special, too. Upon finding the alien ruins, he had hooked himself up to an alien machine, a sort of mental waldo. The same device had killed the Bellerophon's captain when he tried it out, but Morbius survived (barely). Per his report (in yet another stultifying monologue), it doubled his intelligence, allowing him to create Robby and the other marvels of his Altairan residence.

While this tour is going on, the invisible monster slips aboard the C-57D again past increased defenses, for what sinister purpose, we don't yet know. Back at the doctor's ranch, Adams is trying to get Morbius to give up the secrets of the Krell to humanity, but Morbius doesn't feel the human race is ready. The conversation gets heated. Adams and Ostrow return empty handed only to find that the unseen Altairan has killed a member of the cruiser's crew. It left behind this remarkable footprint, which Ostrow recreated in plaster.

Amazingly, Adams does not throw anyone in the brig for dereliction of duty this time. Instead, he holds a funeral for the lost crewman.

Again, there's no way 18 men were cooped up in that thing for a year.

That night, the beast comes back with a vengeance. The ship's energy barriers and combined weaponry are almost useless against it and more crew die.

Right after the attack, we are shown this scene. If you haven't figured out what's causing the attacks by this point, you may need to stay after class for extra assignments.

Adams and Ostrow rush back to the Morbius estate, where their passage is blocked by Robby. They whip out their guns (of course) but those are quickly neutralized. Altaira intercedes to let them in. Shortly thereafter, Ostrow shows up with three burns on his forehead – he has used the mind waldo, which has given him tremendous mental powers. They are too much for him, however, and he soon succumbs, but not before revealing that the monster is indeed a manifestation of Dr. Morbius' subconscious mind created by his link with the Krell's machines!

The tenderest scene in the movie

Adams confronts Morbius with the knowledge, explaining that Morbius unconsciously killed the crew of the Bellerophon when they wanted to leave the planet. He started killing the crew of the U-57D when they threatened to take Altaira away from him.

The beast of Morbius' id now manifests even when the doctor is awake, coming after Adams even in the strongest of Krell sanctums. Adams, of course, whips out his gun, threatening to kill Dr. Morbius to stop the monster (even though we saw Robbie deactivate the blaster just minutes before).

Dr. Morbius throws himself in front of the door, castigating and disowning the id monster's existence. The beast subsides, but Morbius is now dying (for some unknown reason). With his last wish, he commands Adams to activate the Krell city's self-destruct mechanism.

This gives Adams enough time to take Altaira and Robby onto the U-57D, which is all fixed now despite "the book" saying a repair couldn't be done. Hugging on the bridge in front of the 14 of his remaining sex-starved, uncontrollable crew, they watch as Altair IV explodes.

The secrets of the ages? Ah, who needs 'em.

Roll credits.

After Action Report

I didn't like this move. We didn't like this movie. The characters are all wretched (including the drunken cook whose subplot involving the plying of Robbie for manufactured booze wasn't worth discussing). Commander Adams, if he turns in an unvarnished report, should be up for court martial several times over. Walter Pidgeon has one setting, and he's left on it for too much of the movie. Despite the film's not overlong running time, it often dragged.

Most disturbing is the anti-feminism, egregious even for these less-than-enlightened times. As fellow traveler Erica Frank notes, "It's especially worth a sharp look when the story is science fiction, where the underlying message includes "so much of society has changed — these are the parts that were worth keeping."

So is there anything to like about this movie? Well…

The touters are correct. It is beautiful, from its set design to its special effects to its wide wide Cinemascope aspect ratio. Cinematorapher George J. Folsey, whose credits go back to 1920 did a fine job.

The soundtrack, in particular, by avante garde electronic musicians Bebe and Louis Barron is just incredible. I've only heard its like in the theme of Dr. Who and the music and effects of the British marionette show, Space Patrol. It makes me want to break out some electronic components and build some modulating circuits for my own experimental purposes.

The background of the Krell and the Freudian id monster weren't bad as far as science fiction goes. One could easily find such devices in a story from any of the SF mags of the era or before.

In short, we liked everything about the movie but the movie. I'm almost tempted to re-record the dialogue with an entirely new script, preserving the spectacular visuals and sound.

Perhaps I don't have to. I understand that the new SF anthology show, Star Trek, has such lush production values that it will essentially look like Forbidden Planet on television. As long as it doesn't hew too close to its predecessor.

As for rating Forbidden Planet. call it five stars for production values, three for the setup, and one for the execution…

Don't miss this weekend's episode of The Journey Show, taking you on a whirlwind tour of the exciting new field of Japanese animation!

![[October 8, 1965] Handle with Care (<i>Forbidden Planet</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651010a-672x372.jpg)

![[October 6, 1965] Go, baby, go! (<i>Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/99f21f4b8fd97f8ef16ec5f38a6030ae-2-500x372.png)

![[October 4, 1965] Galaxy Bore (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Galaxy 4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651004chumbleyonpatrol-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1965] Gimmickry (November 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/1965-11-IF-cover-645x372.jpg)

![[September 30, 1965] Big and Little Bangs (October 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650930cover-672x372.jpg)

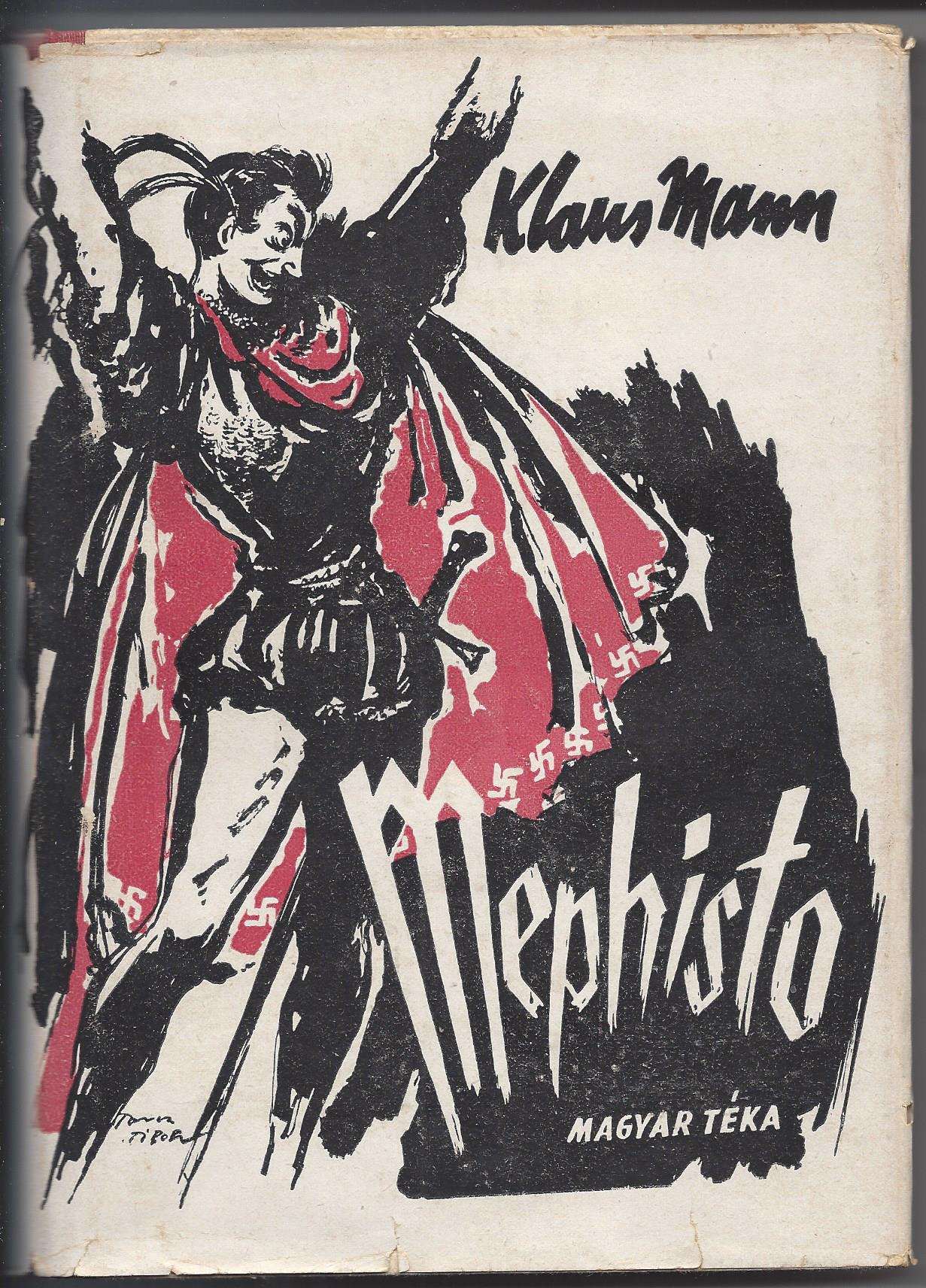

![[September 28, 1965] Of Art and Freedom: The Rolling Stones Riots and the <i>Mephisto</i> Case](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/1018-672x372.jpg)

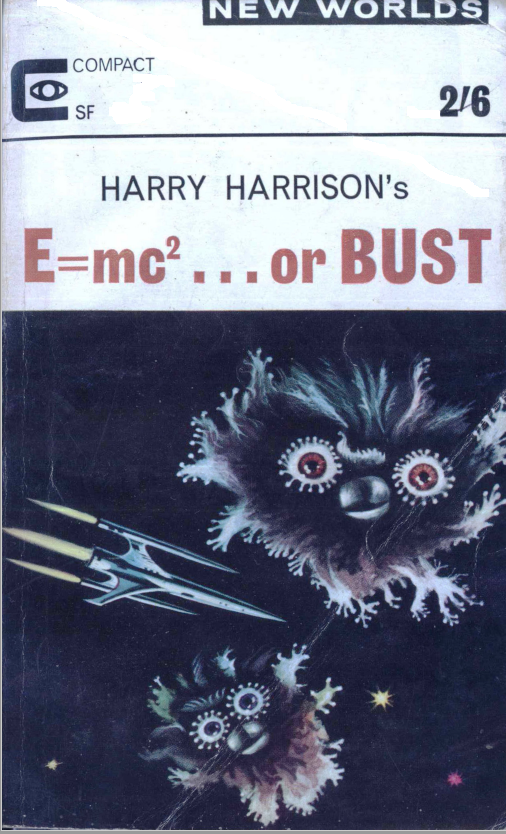

![[September 26, 1965] Allegory and Mythology <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, October 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/sf-nw-october-1965-672x372.png)

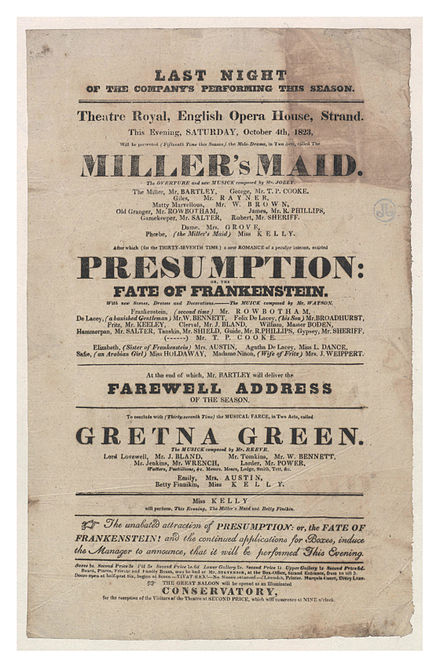

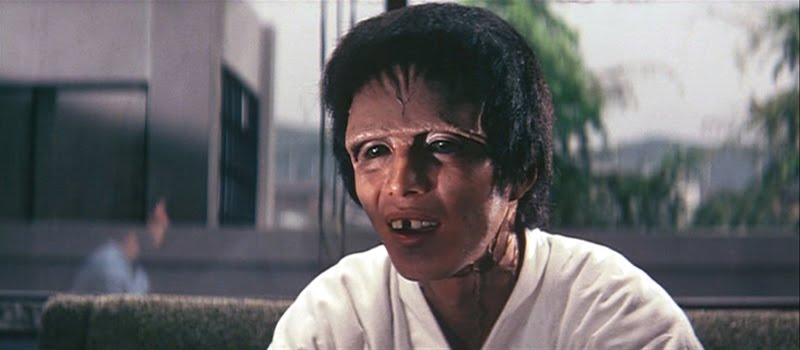

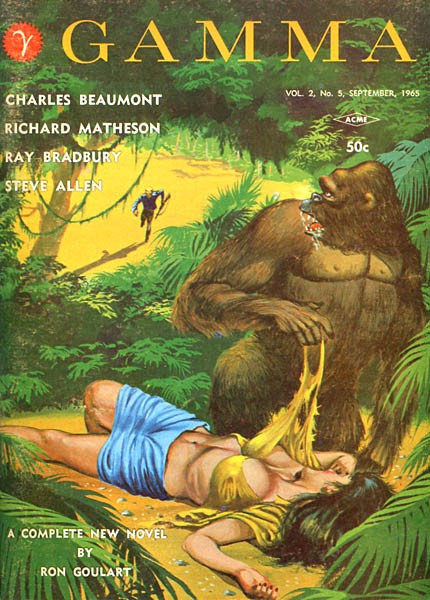

![[September 24, 1965] False Advertising (<i>Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster</i> and a brief history of Mary Shelley's creation on film)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/4d6e7604f0053e87ac44cfd4c8fb9dd0e9de58b6r1-749-920v2_hq-2-672x361.jpg)

![[September 22, 1965] Foul! (September Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650922covers-656x372.jpg)

![[September 20, 1965] Unfinished Business (October <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650920cover-672x372.jpg)