by Lorelei Marcus

I recently watched and reviewed the new Monkees movie, Head—a depressing and existential capper to both the TV show and The Monkees band itself. I ended the article questioning whether the members of The Monkees would be able to weather the deliberate self-sabotage of their band, or be doomed to obscurity by disappointed fans. While I appreciated Head for what it was, reception has been mixed and, in the main, less than positive. It seemed the end of The Monkees would be a quiet, tragic one.

Until April 14 of this year. Scheduled opposite the Oscars, NBC broadcast a TV special entitled 33 1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee. While half the country was dazzled by movie stars and award ceremonies, I watched the last hurrah of Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd. It was an unusual finale, and not far removed from Head stylistically and, perhaps, in intent. But in contrast to the grim movie, I thought I saw a glimmer of hope.

The special starts strong with the surreal introduction of a pair of musical brainwashers: ebullient Brian Auger (he introduced "Drimble Wedge and the Vegetation" in the movie Bedazzled) and the enigmatic Julie Driscoll—the front-folk for the popular British band, The Trinity. The Monkees are summoned in on Star Trek-ish transporters and then trapped in giant tubes, hypnotized by a strange machine until they have lost all identity and free will, rejecting their own names for "Monkees No. 1-4". This and their subsequent (though not immediately following) musical number, "Tinman", wherein they play wind-up versions of themselves, make clear their still strong feelings of being manufactured and forced into the band-idol role.

But unlike Head, the TV special offered glimpses of what The Monkees could be if given their freedom.

Even trapped with the tubes, The Monkees are given license to dream their most desired fantasy (essentially, what songs each might sing if they had complete license), and we view these dreams in the first four vignettes of the special. Micky sings a soulful duet of "I'm a Believer" with Julie Driscoll. He is at home on the stage, comfortable with being a vocal performer.

Peter sings a soft, mystical ballad with plenty of Indian influence. The artistry of both the lyrics and the music emphasize his skill as a storyteller and musician. They also echo his role in the pivotal Eye of the Storm scene in Head.

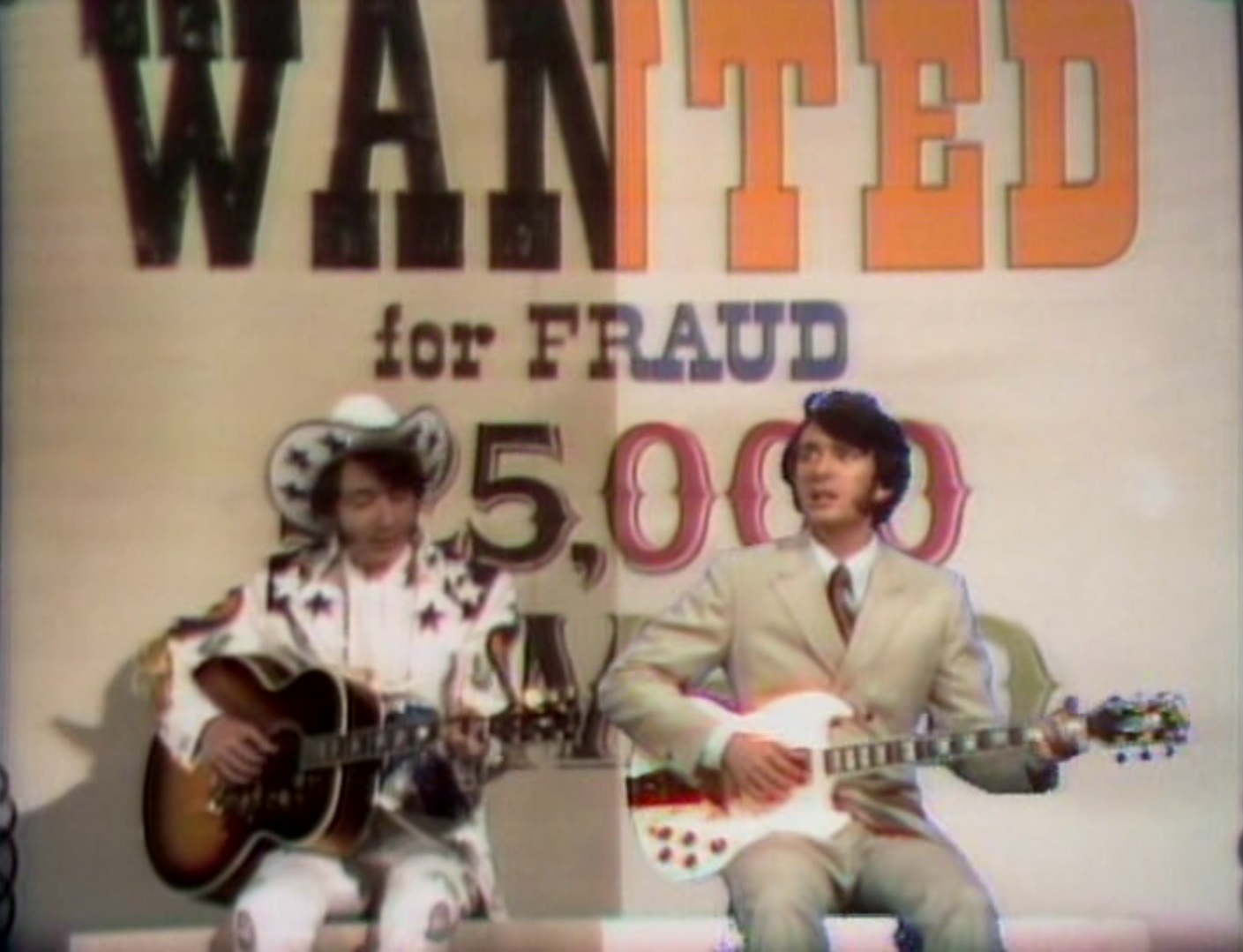

Mike's act involves a warring duet…with himself. There is both humor and commentary as the stereotypical Texas country boy Mike and the slick, suit-wearing, city boy version of Mike compete for dominance in the song.

Finally, Davy stars in the most fantastical and theater-like number where he sings and dances in an oversized room with several female partners dressed like fairy-tale-inspired dolls. He also demonstrates his prowess as a performer, and he seems the most entwined and comfortable with his (manufactured?) Monkees persona.

These acts are perhaps the best part of the special, with each Monkee getting to express his own personality and talents. However, it does not last, and from there, the show begins to lose its way.

First, we get a random and slightly out of place modern dance piece performed against a volcanic/lava-lampy/biological matte background, that seems to be a depiction of evolution and creation. This is in service to a motif introduced by Auger as Charles Darwin, describing the evolution of music.

Then, we get a musical skit where the Monkees are dressed as actual monkees. It might also be an homage to the first act of the movie 2001, the music is only passable, and a bit too similar to the next skit.

Here, the Monkees reach their ultimate form as a manufactured rock band in a full blown '50s nostalgia concert, poking fun at the success of idols like Elvis and The Beatles. There are some impressive guest stars, including Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Little Richard, but as with the prior two segments, the scene goes on for much too long, losing meaning with every new dancer and musical guest brought on.

As the concert reaches its climax, the film literally burns apart, and we are left with Auger and Driscoll declaring (in their native accents, as opposed to the weird German of Auger and the…alien harpy of Driscoll) that they're tired of their brainwashing role. All they want is total freedom. They warn, however, that such freedom could result in total chaos.

At first, their caution seems unfounded as we cut to Davy singing a normal and pleasant song atop a set of scaffolding. Then, in the ensuing silence after he finishes, the camera pans to the cluttered ground floor, reminiscent of a theater storage room. Peter arrives, and without a word, sits and plays a masterful Baroque fugue on an electric piano. His performance is a poignant moment, and it feels like a long-deserved recognition of his immense musical talent…also a kind of goodbye, for the papers have since announced that Tork left the band after this special.

Then, just as casually and quietly, Micky sits at his drumset and Mike picks up his guitar. They take a moment to tune, and then they begin to play a new song: "Listen to the Band." For a little while, everything feels right again. The band is together, the music is good. They appear to be where they want to be.

The mood elevates as suddenly a whole orchestra joins in, and a new singer takes over for Mike. There is excitement in the dancing and flashing colors and swelling music—it's all a bit reminiscent of the final recording of The Beatles "All You Need is Love" as seen on year-before-last's satellite broadcast of Our World. But then confusion sets in as the Monkees disappear from view in the massive crowd, and the music itself devolves into a cacophony of blended, formless sounds. This also goes on for far longer than is comfortable, until the iconic Monkee's gorilla himself closes the book on the special, its cover titled, "The Beginning of the End."

Overall, I didn't enjoy this special as much as Head. It felt much less thought-out and clever, lacking a cohesive narrative. To a degree, I think this was intentional. Time and again, both The Monkees and their music gets lost, drowned out by other musicians and strange editing. In a specific sense, it is a direct metaphor for what happened to The Monkees. In a general sense, it symbolizes the fear of being lost in the tide of change and innovation. Or perhaps it represents simply being overwhelmed by the pressures of modern sociery. Either way, it didn't make for the best viewing experience.

Still, I see a future where The Monkees do pull through. Each of them has immense talent and an ambition to succeed in some aspect of show business. In the beginning of the special, we see what they can do, and even if it's drowned out by the end, that doesn't mean they can't resurface. In fact, as their band crumbles apart, disappearing may be the best path for a while, until they've thoroughly shaken off their former legacy and started fresh.

It's bittersweet having to say goodbye, and I wish it could have been done more elegantly, but I doubt this is the last we'll see of Micky, Peter, Davy or Mike. It'll just be when they do come back, they'll have created something completely new.

"Listen to the band…"

33 1/3 Revolutions per Monkee was a paving stone in the path toward that innovation, and while it wasn't fully successful, I can see the potential within it for future success.

Three stars.

![[May 8, 1969] Cooked in the Chrysalis (The Monkees TV special: <i>33 1/3 Revolutions Per Monkee</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/690508tubes-672x372.jpg)

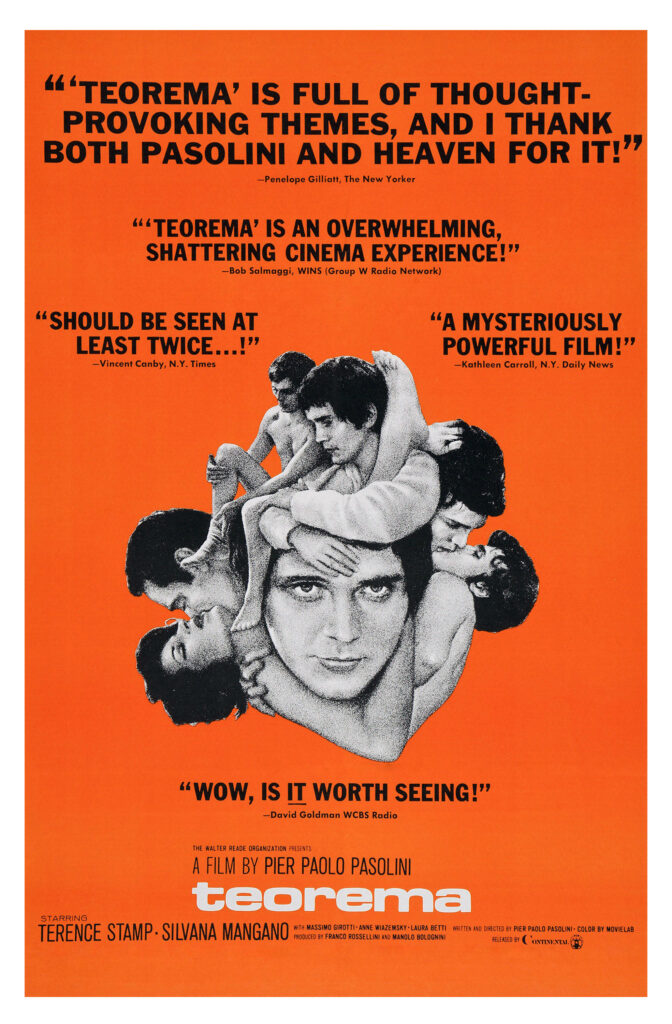

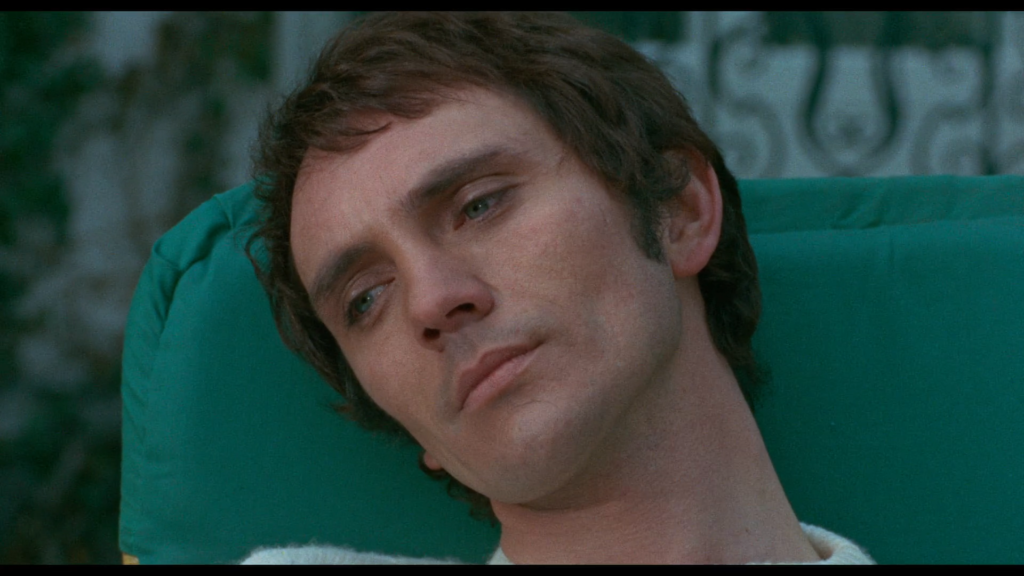

![[May 6, 1969] Touched by an Angel: <em>Teorema</em> (<em>Theorem</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/MV5BODA1ZWZiZWYtYjVhMC00ZGQxLWI1Y2MtM2VmYjg2MzQyMDM3XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMjUzOTY1NTc@._V1_-672x372.jpg)

![[May 4, 1969] Navigating the Wasteland #3 (1966-69 in (good) television)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690504laughin-672x372.jpg)

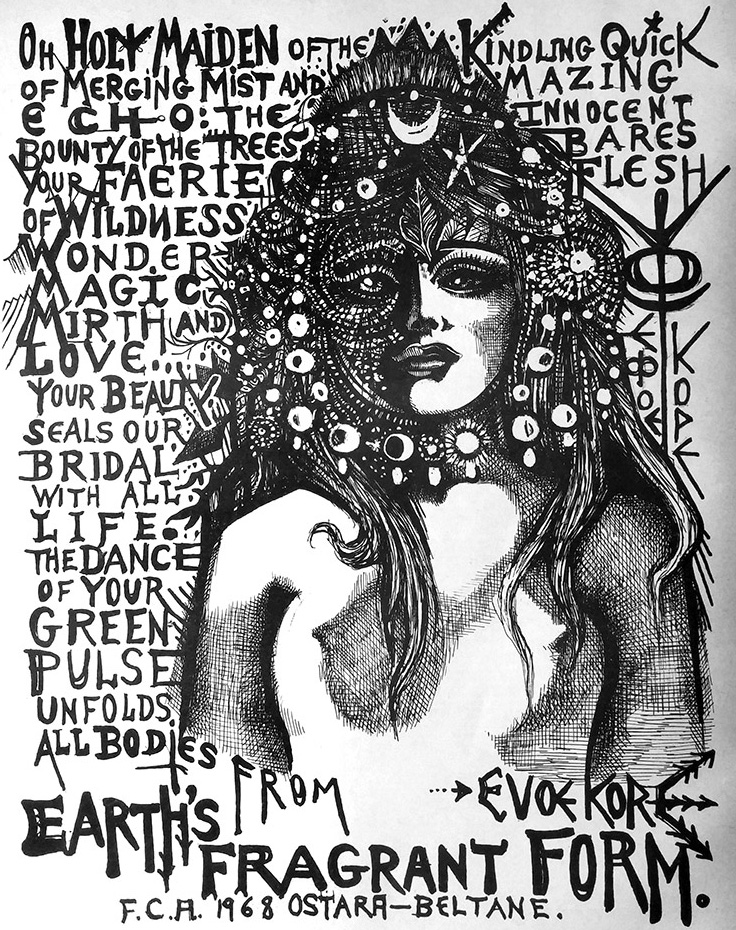

![[May 2, 1969] The Lusty Month of May: Beltane and Feraferia](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690502_Korythalia_issue2_pg8-672x372.jpg)

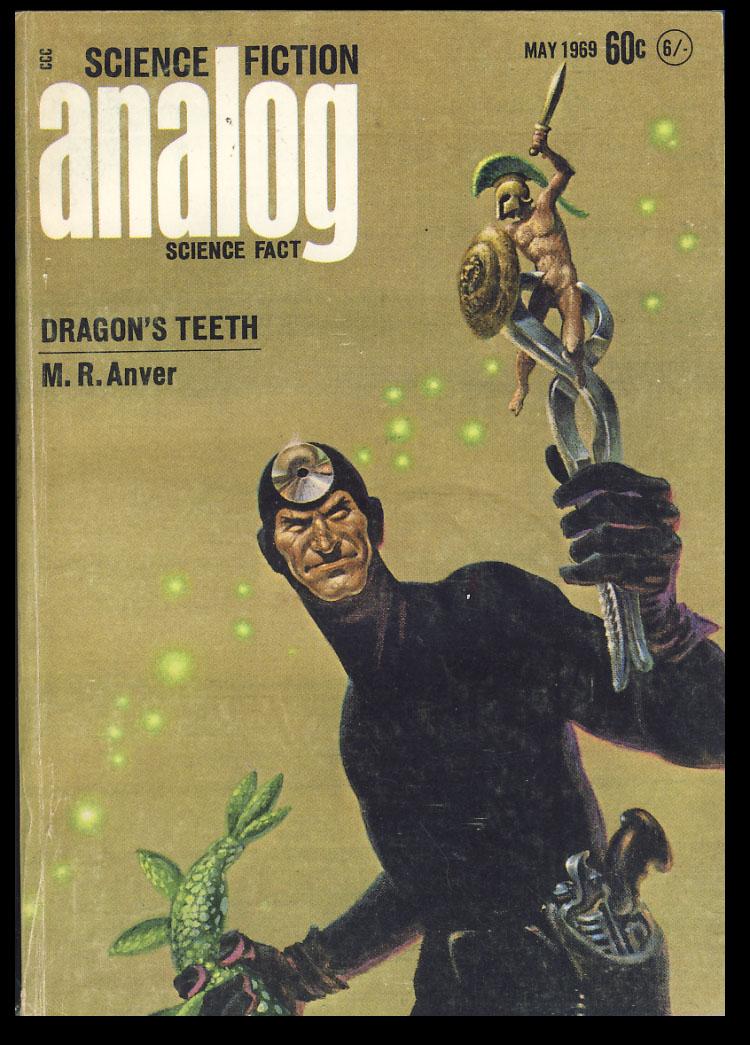

![[April 30, 1969] Eulogies (May 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690430analogcover-672x372.jpg)

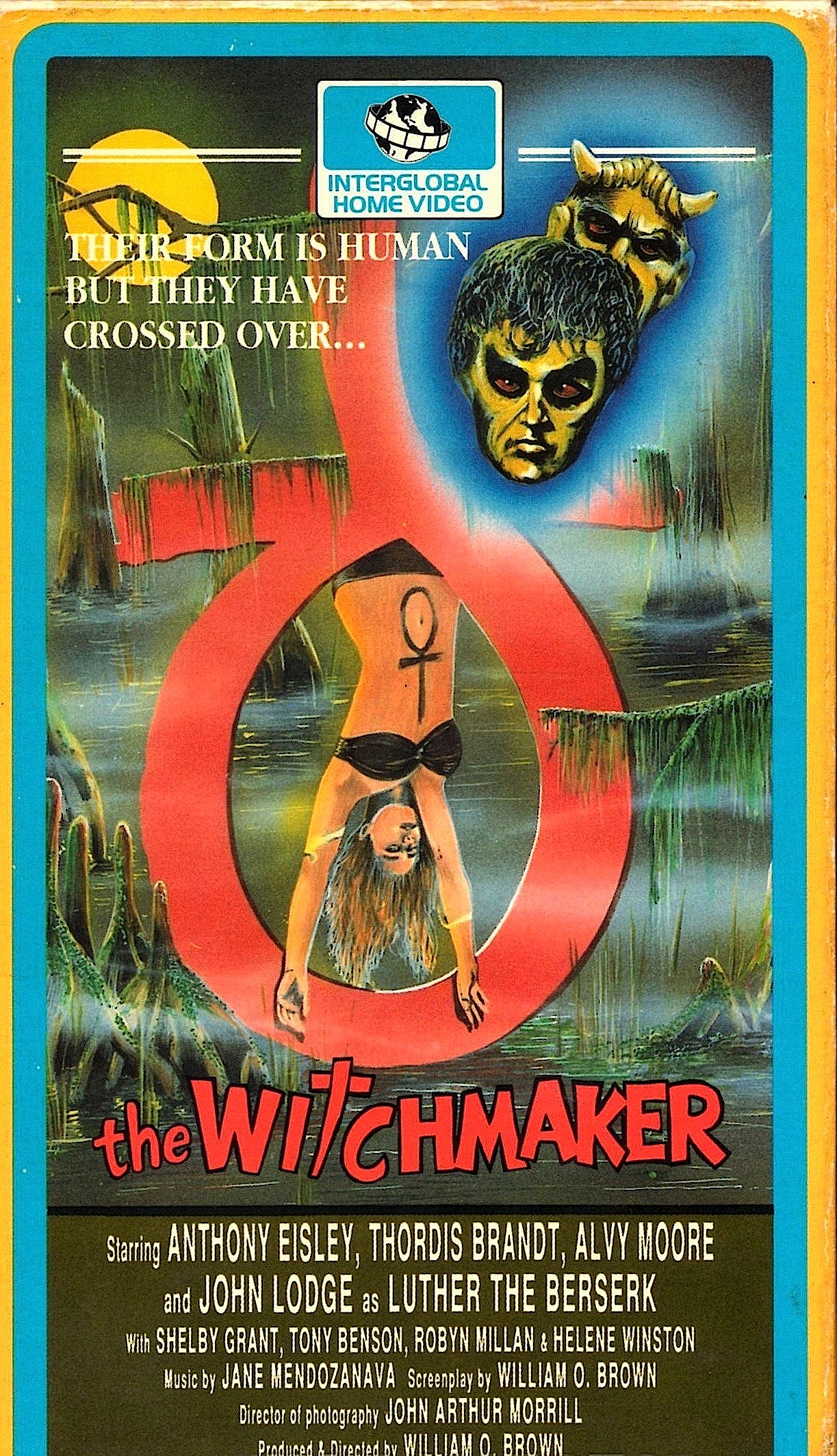

![[April 28, 1969] Cinemascope: Witchmaker, Witchmaker, Make Me A Witch: "The Witchmaker" (a movie) and "The Body Stealers" (a flick)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690428posters-672x372.jpg)

Poster for The Witchmaker

Poster for The Witchmaker

No tits please, we're Americans

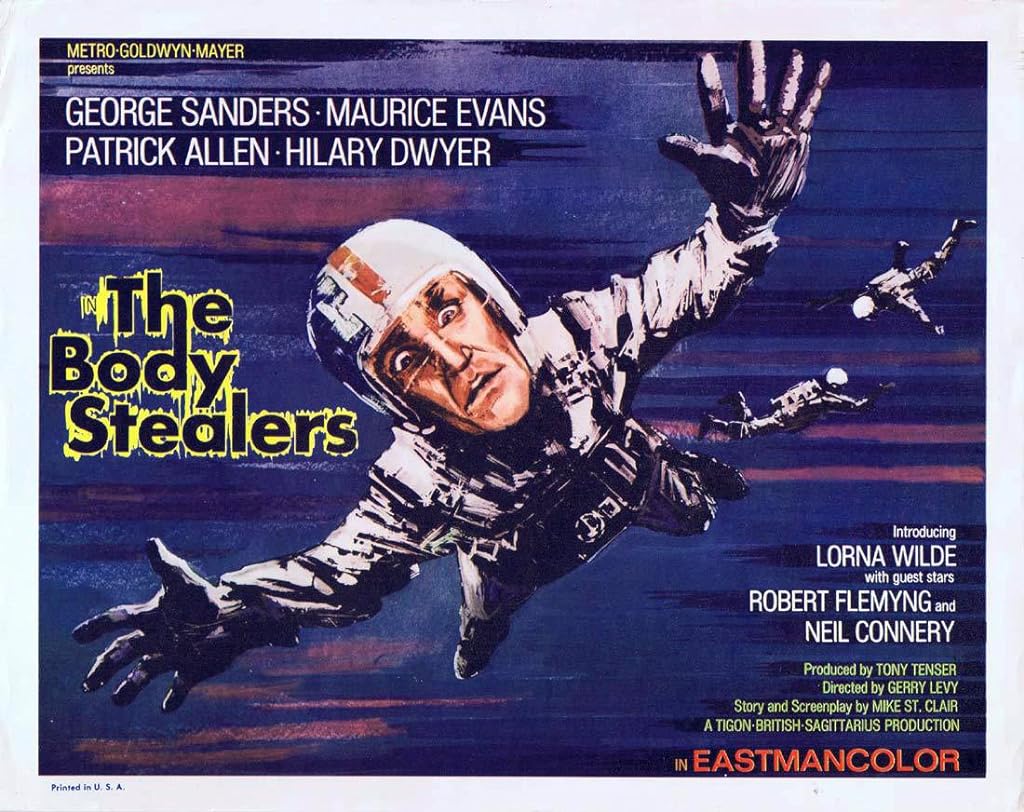

No tits please, we're Americans Poster for The Body Stealers

Poster for The Body Stealers Bob Megan: rugged, sexy and a knitwear aficionado

Bob Megan: rugged, sexy and a knitwear aficionado Recognise this? You should

Recognise this? You should![[April 26, 1969] Downbeat (May 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690424coverfsf-667x372.jpg)

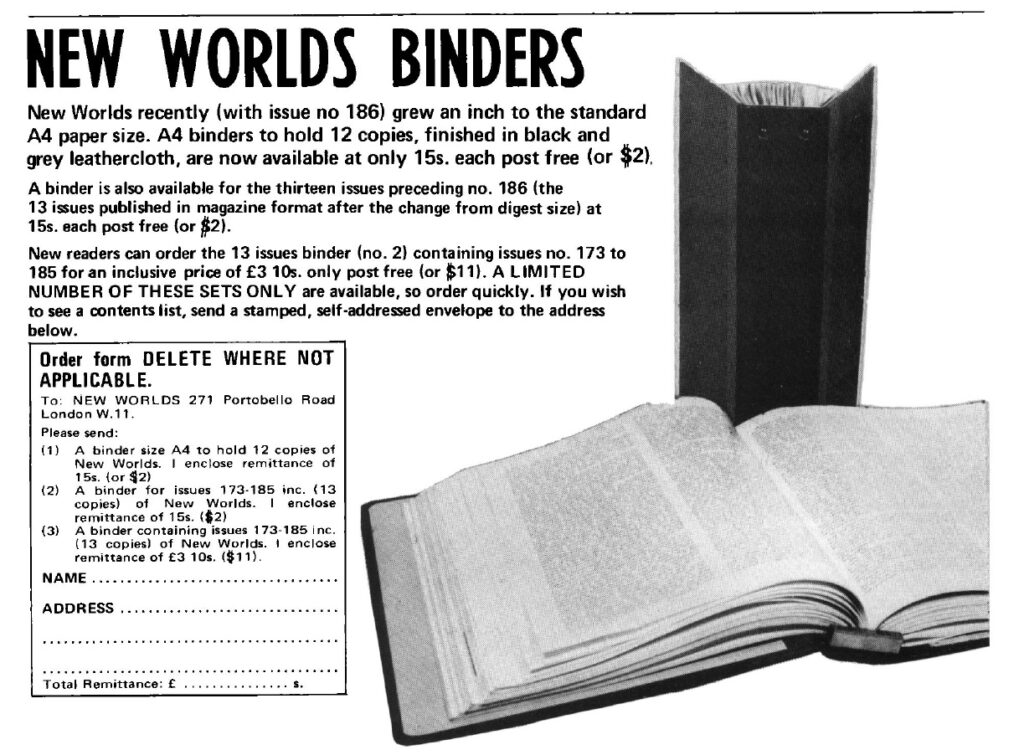

![[April 24, 1969] The Strange New Normal <i>New Worlds</i>, May 1969](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/New-Worlds-May-1969-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Cover by Gabi Nasemann  Photo by Gabi Nasemann

Photo by Gabi Nasemann  Image by Mal Dean

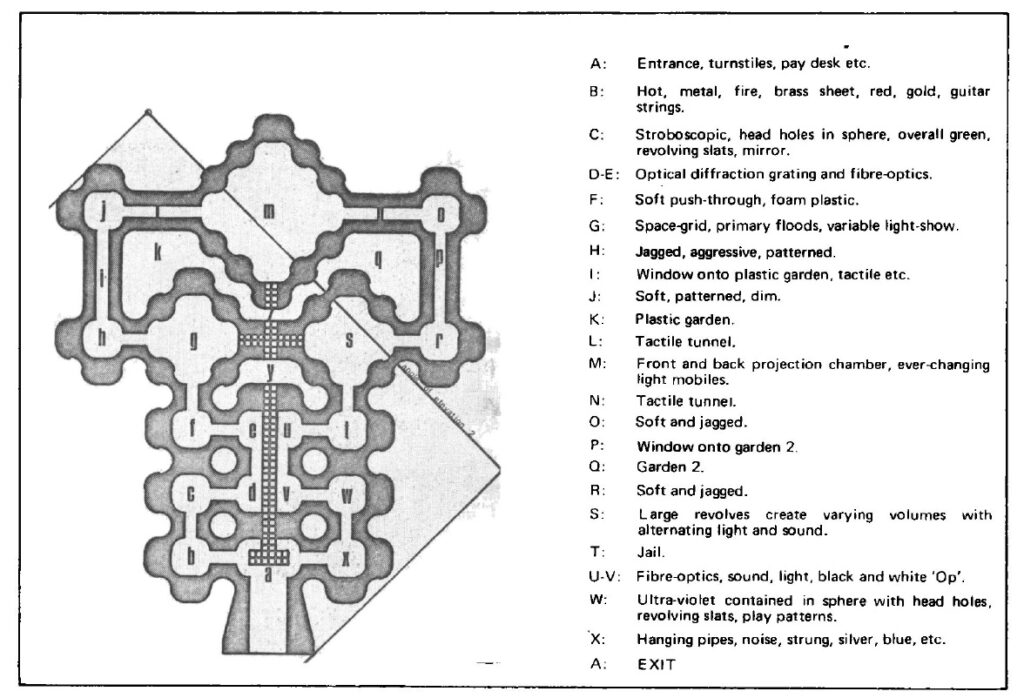

Image by Mal Dean  A map of the Girvan Fun Palace, Image by Unknown

A map of the Girvan Fun Palace, Image by Unknown

Image by Mal Dean

Image by Mal Dean  Photo by Gabi Nasemann

Photo by Gabi Nasemann

![[April 22, 1969] Corpse or Cocoon? – (the Monkees movie <i>Head</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690422headtitle-672x372.jpg)

![[Apr. 20, 1969] Are Phoenixes Rising from ASFR's Ashes?](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690418coverasfr15-672x372.png)