What an immediate world we live in. Think about life six hundred years ago, before the printing press, when news and knowledge were communicated as fast as a person could talk, as fast as a horse could trot. Think about life two hundred years ago, before the telegraph knit our nation together with messages traveling at the speed of light. Think about the profound effects movies, radio, and television have had on society. With each advancement, the globe has shrunk. One can now hear broadcasts in virtually any language from the comfort of one's home. One can get news as it happens from the other side of the planet.

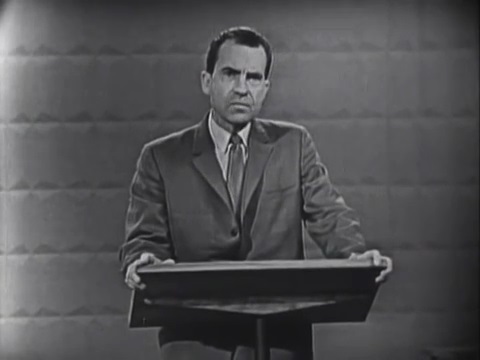

And, for the first time, the American people can, through our representatives in the media, have a direct conversation with our presidential candidates. For yesterday, thanks to the marvel of modern television, Senator Kennedy and Vice President Nixon were able to discuss matters of national urgency in the first-ever televised presidential debate, on September 26.

I can't stress enough how exciting the experience was for me, as I imagine it was for you. For the first time, the candidates felt like people. Their platforms were clearly articulated. By the end of the event, I had a much clearer idea of what my choices would be come November.

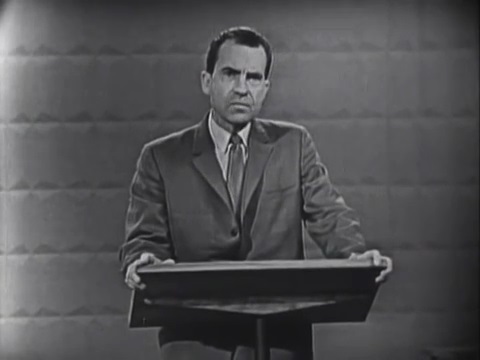

It was an interesting contest, and I think both candidates acquitted themselves well. Kennedy began the event rather stiffly, but by the midpoint, he had hit a fiery, engaging stride. Nixon affected a rather deferential mien, which surprised me. As a result, he came off as a gentleman, but a bit complacent. He also seemed, at times, to struggle for words. Not often, but it suggested a touch of exhaustion. I shouldn't be surprised, given the man's campaigning schedule.

As for the substance of their remarks, during this hour-long debate specifically on domestic matters, I took four pages of hastily scrawled notes. I'll try to digest them into something short and cogent.

The candidates were given eight minutes for opening speeches. Kennedy led off, linking freedom with economic prosperity. So long as the world remains half slave and half free (paraphrasing a famous Republican, how the times have changed), the way for freedom to endure is for economic progress to be made. He touted the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) as a model for future, government-led success. He acknowledged the moderate prosperity of the post-War era, but charged that we must do better, that we can do better. Interestingly, this is the only time that either of them addressed the strong racial inequality in our country. Nixon was conspicuously silent on the issue–perhaps he hopes to wrest the South from Democratic control.

Nixon, unlike Kennedy, used the full span of time allotted for the opening speech. For the first half, he was strikingly defensive. America was not standing still, he said, a tone of desperation creeping into his voice, and a sheen of sweat on his chin. The Vice President fared better as he shifted to propounding his own agenda. He maintained that the Republicans know the secret to progress, and that the Eisenhower era was far more successful than the Truman era. He ended his comments with a dig against Kennedy: "I know what it means to be poor." This is true, but so long as the Republican party is the party of big business, I don't think it matters.

Then a panel of four reporters presented a series of questions to the candidates. Three of the ten dealt with whether or not Kennedy and Nixon were qualified to be President. In Kennedy's case, the issue was age, to which Kennedy replied that he and Nixon had both been in governmental service since 1947. The Senator also noted that Lincoln (again!) had the shortest of political resumes and yet was one of our greatest Presidents. For Nixon, the issue was eight years of ineffectiveness. Had he done anything memorable as Vice President? Nixon said he had; Kennedy disputed Nixon's claimed accomplishments. It was pretty damning that Eisenhower, himself, said he needed a week to recall a major Nixon accomplishment–and he turned up empty a week later.

Things got more interesting, for me, when substantive policy issues were addressed. Regarding ongoing farm subsidies, Kennedy insisted that they were necessary given the volatile nature of the agriculture business, the relative weakness of the farmer in his market, and the importance of the food production sector. Nixon agreed that subsidies must continue while the wartime surpluses remain, but that the farmer must ultimately be weaned off the government teat.

In response to a question regarding the national debt, Kennedy asserted that the debt could not be reduced before 1963, but that his expanded programs would be paid for by the growing economy they would guarantee. Nixon noted that the government would have to front payment for the programs before it came back as taxes, and he insisted that Kennedy's programs were too "extreme." The only way to pay for them would be to raise taxes or go into inflation-causing debt, both of which would hurt the American people.

Perhaps the subtlest issue of the debate was teachers' salaries. Both came out in favor of it. But Nixon has a record of voting against it. The Vice President says he worries that involvement of the federal government will reduce the freedom the teachers have to instruct as they wish. Kennedy dismissed this argument noting that the bill he supported in February of this year had no such strings attached–the federal government would simply give money to the states, which would then spend it as they saw fit. Nixon noted, however, that this would incentivize the states to simply diminish their contribution to education in an amount equal to what the federal government provided. Interesting points.

The highest drama ensued when Kennedy was asked if he would be more effective as a President in getting bills passed than as a Senator. Kennedy noted that he had no trouble getting his proposals passed in his legislative chamber; it was the obstinate Republicans in the House and in the White House that blocked them. With him as President, his policies would be effected. Nixon, rather unconvincingly, said it was not Eisenhower's veto that blocked Kennedy, but the will of the people that veto represented.

The spirited debate continued into the next question, regarding Nixon's ability to lead. The Vice President rather bashfully averred that whomever the people voted for would be an effective President–but the people wouldn't support someone who espoused extreme measures.

Kennedy countered forcefully that a $1.25 minimum wage was not extreme, that medical insurance for those over 65 was not extreme, and that federal support of education was not extreme. And should he be elected, he implied, those measures will pass.

The last question addressed the issue of domestic Communism. Both candidates expressed their concern over the problem, but it was pretty clear that neither of them were too worried about it. Kennedy noted that the primary threat was external Communism. Nixon urged that we must be "fair" to our people when combating domestic Communism, lest we become too like our repressive enemies. Given Nixon's strong role in the anti-Communist movement a decade ago, this note rang a bit false.

At this point, the candidates were given three minutes to sum up. Nixon stressed that the Soviet Union may be growing faster than the United States, but that's just because they are so much further behind. In 1960, as in 1940, the Soviet Union has just 44% of America's Gross National Product. And while he and Kennedy agreed on general goals, their means were different. I couldn't quite parse out what Nixon's means would be–only what they would not be (i.e. increased federal spending).

Kennedy ended on the offensive. He said he did not want America to sit idly while the Soviet Union closed the economic gap. The Senator said that, if we are happy with the nation as it is, by all means, we should vote for Nixon. But if we're the least bit dissatisfied (and who is ever completely satisfied?), we must vote Democratic. Because America is "ready to move," and Kennedy can get us moving.

The debate had a paradoxical effect upon me as a voter. I was (and am) predisposed to poll Democratic, and seeing Kennedy perform only reinforced that tendency. On the other hand, I feel I have a better handle on the Vice President, and I like him more than I did before the event. Thus, while Kennedy may have "won" the debate, I think both candidates came out winners in terms of presenting themselves as competent, likeable executive possibilities.

More important, perhaps, is the way this debate has presented in a clear-cut fashion, the issues facing the American people. We all have a lot to think about now. And stimulating the cerebral juices is a laudable achievement for a device commonly known as the "idiot box."