by John Boston

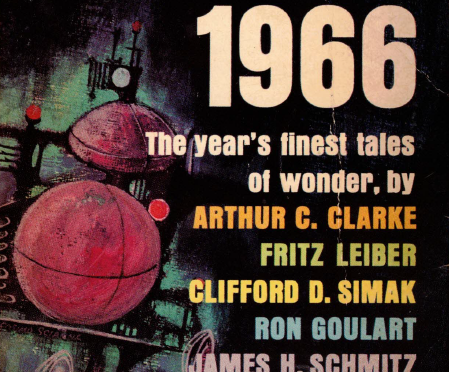

Donald A. Wollheim’s and Terry Carr’s World’s Best Science Fiction: 1966—second in this series—is here, so it’s time for the usual pontificating, hand-wringing, viewing with alarm, etc., as one prefers. This one comes with not one but two blurbs from Judith Merril, their competitor, though the editors say nothing about her anthology series, the next volume of which is due at the end of the year.

The editors have regrettably pulled in their horns a little on the “World” front. There are no translated stories in this volume, unlike the first; the editors claim that they read plenty of them, but them furriners just don’t cut the mustard. More precisely, if not more plausibly, “what they have lacked is the advanced sophistication now to be found in the American and British s-f magazines.” Suffice it to say that there are virtues other than “advanced sophistication” and they may often be found outside one’s own culture.

by Cosimo Scianna

Nor is there anything here from any of the non-specialist markets that have been publishing progressively more SF in recent years. The only item here that did not originate in the US or UK SF magazines is Arthur C. Clarke’s Sunjammer, originally in Boys’ Life but quickly reprinted last year by New Worlds, and then by Amazing early this year.

So it’s a rather insular party. But my main complaint last year was that too much of the material was too pedestrian, and the book excluded writers who are pushing the envelope of the genre, like Lafferty, Zelazny, Ellison, and Cordwainer Smith. The editors seem to have been listening. This year they’ve got Ellison and Lafferty, though they seem to have missed their chance at Smith, and Zelazny is still among the missing. More importantly, the book as a whole is livelier than its predecessor.

This is not to say the pedestrian has been entirely banished. Witness Christopher Anvil’s The Captive Djinn, the only selection from that rotten borough Analog, yet another story about the clever Earthman outwitting cartoonishly stupid aliens. Anvil has written this story so often he could do it in his sleep, and most likely that is exactly what happened.

There is a lot more of the standard used furniture of the genre here, but at least it’s mostly done more cleverly and skillfully than dreamed of by Anvil. In Joseph Green’s The Decision Makers (from Galaxy), Terrestrials covet the watery world Capella G Eight, but it’s already occupied by seal-like amphibians with group intelligence though not much material culture. Is this the sort of intelligence that should ordinarily bar colonization outright? The “Conscience”—a bureaucrat in charge of making these decisions—thinks so, but proposes to split the baby, allowing colonization but providing that the humans will alter the climate to provide more dry land for the amphibians. Of course, behind the bien-pensant speechifying, a still small voice says, “We’re just now starting to get rid of colonialism here, and you want to start it up again?” And another: “Ask the American Indians about the promises of colonists.”

Less weighty thoughts are on offer in James H. Schmitz’s Planet of Forgetting (from Galaxy), involving a fairly standard space war scenario with chase on unknown planet, with the wrinkle that some of the local fauna seem to be able to make people briefly forget where they are and what they are doing. At the end of this smoothly rendered entertainment, suddenly the wrinkle becomes a mountain range.

Similar cleverness-as-usual is displayed in Fred Saberhagen’s Masque of the Red Shift (from If), one of his popular Berserker series, in which a disguised Berserker robot appears and wreaks havoc on a spaceship occupied by the Emperor of the galaxy and his celebrating sycophants. But it is promptly outsmarted and done in by the Emperor’s brother, who is resurrected from suspended animation and lures the Berserker into the clutches of a “hypermass,” which seems to be what scientists are starting to call a “black hole.” (Though on second thought, I’m not sure that “cleverness” is quite le mot juste for a story that falls back on the dreary cliche that a galaxy-spanning human civilization will find no better way to govern itself than an Emperor.) Jonathan Brand’s Vanishing Point (If) is an alien semi-contact story, in which the functionaries of the Galactic Federation have created an artificial habitat, a sort of Earth-like theme park complete with human curator, for the human emissaries to wait in and wonder what is really going on.

Engineering fiction is represented by Clarke’s slightly pedantic Sunjammer (as noted, Boys’ Life by way of New Worlds), concerning a yacht race in space, and by Larry Niven’s livelier Becalmed in Hell (F&SF), whose characters—one of them a brain and spinal column in a box, with vehicle controlled by his nervous system—get stuck on the surface of Venus (updated with current science) and have to improvise a primitive solution to get home.

There are a couple of near-future satires representing very different styles and targets of the sardonic. Ron Goulart’s Calling Dr. Clockwork (Amazing) is a lampoon of the medical system; protagonist visits someone in the hospital, faints at something he sees there, wakes up in a hospital bed himself attended by the eponymous robot doctor, and can’t get out as his diagnosis shifts and things seem to be falling apart in the institution. Fritz Leiber’s The Good New Days (Galaxy) is a more densely populated slice-of-slapstick extrapolating the welfare state, with a family living in futuristic but cheaply made housing (“They don’t build slums like they used to,” complains one character), with the TV on every minute, and Ma trying to avoid the demands of the medical statistician who wants her vitals, and everyone struggling to get and keep multiple make-work jobs (the protagonist just lost his job as a street-smiler), and things are all falling apart here, too, and a lot of the sentences are almost as long as this one. The two stories are about equally amusing, which means above standard for Goulart and a little below standard for Leiber.

So that’s the ordinary, and a higher quality of ordinary than last year.

A few items are unusual if not extraordinary. R.A. Lafferty’s In Our Block (If) is an amusing tall tale about various odd characters with unusual talents residing in the shacks on a neglected dead-end block, like the woman who will type your letters but doesn’t need a typewriter (she makes the sound effects orally), and the man who ships tons of merchandise out of a seven-foot shack without benefit of warehouse. It has lots of slapstick but not much edge, unlike the best by this idiosyncratic writer. Newish writer Lin Carter (two prior appearances in the SF magazines, a lot in the higher reaches of amateur publications), in Uncollected Works (F&SF), extrapolates the old saw about monkeys on typewriters reproducing the works of Shakespeare, in the direction of Clarke’s The Nine Billion Names of God, leading to an unexpected and subtle conclusion.

In Vernor Vinge’s Apartness, from the UK’s New Worlds, the Northern War has destroyed the Northern Hemisphere, and generations later, an expedition from Argentina discovers people encamped in Antarctica, living in primitive conditions, who prove to be the descendants of white South Africans who fled from the uprising that followed the war and eliminated whites from the continent. (Interesting that this American writer didn’t find a market for it at home.) They are not pleased to be discovered by darker-skinned explorers and try to drive them off. The well-sketched background makes this more than an exercise in irony or just revenge.

On to the extraordinary—three of them, not a bad showing. Traveler’s Rest, by David I. Masson, also from New Worlds, depicts a world where time varies with latitude, passing slowly at the North Pole (though subjectively very fast), where a furious—and possibly futile—high-tech war is in progress with an unknown and unseeable enemy. Life proceeds more mundanely in the southern latitudes. Protagonist H is relieved from duty, travels south, reorients himself to current society, establishes a career, marries and procreates over the years. He's known now as Hadolarisondamo, since names are longer in the slower latitudes. Then, middle-aged, he is called back to duty, and arrives 22 minutes after he left. This world’s nightmarish quality is highlighted by the dense mundane detail of the normal life of the lower latitudes; the result is a tour de force of strangeness.

Harlan Ellison’s “Repent, Harlequin!” said the Ticktockman (from Galaxy) is a sort of dystopian unreduced fraction. In outline, it’s a simple story of a future world where punctuality is all; if you’re late, your life can be docked. One man can’t take it any more and dresses up in a clown suit and goes around disrupting things until he gets caught by the Master Timekeeper (the Ticktockman), brainwashed, and forced to recant publicly—though the end hints that his legacy lives on. In substance, it’s business as usual; in style, it’s a sort of garrulous stand-up routine, and quite a good one. It’s best read as a purposeful affront to the usual plain functional (or worse) prose of the genre (a reading consistent with the story’s theme) and a persuasive argument for opening up the field a bit stylistically.

The other outstanding item here—best in the book to my taste—is Clifford D. Simak’s Over the River and Through the Woods (Amazing), in which a couple of strange kids appear at a farmhouse in 1896 and address the older woman working in the kitchen as their grandma. The gist: Ordinary decent person confronted with the extraordinary responds with ordinary decency. It’s plainly written without a wasted word, deftly developed, asserting its homely credo with quiet restraint—a small masterpiece amounting to a summary of Simak’s career. Simak is one writer who should ignore Ellison’s advice—and vice versa, no doubt.

The upshot: Not bad. Better than not bad. The field is taking small steps away from business as usual, and the usual seems to be getting a little better. The kid may amount to something some day.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

It's a remarkably gormless, out of touch selection for 'Best SF of 1965.'

Here are the Nebula awards (and nominees) for 1965, which seem rather more on point and likely to stand the test of time —

https://nebulas.sfwa.org/award-year/1965/

I assume the out-of-touch selection is rather more down to Wollheim than Carr. It's a shame.

Apparently, science fiction written by women is also "lacking in advanced sophistication", since every single story in this anthology was written by a man.

Or maybe its sophistication is too advanced for the editors.

Interestingly, the rather long Nebula list Mark points to lists only one piece of short fiction written by a woman, "Lord Moon" by Jane Beauclerk from F&SF (which I haven't read, or have forgotten).

Wollheim/Carr's selection may be gormless, but I don't see a whole lot of gorm in that Nebula list, sticking to the short stories and novelettes since the longer items generally won't fit into an anthology of this sort. Nine of the 15 stories from the anthology are also on the Nebula list. Certainly some of the other Nebula-listers would have improved the book. Swapping Lafferty's "In Our Block" for "Slow Tuesday Night" would have been wise. One of the two Disch stories and one of the three Norman Kagan stories, maybe; Ballard's "Souvenir" a/k/a "The Drowned Giant," certainly. What else? I hope Mark doesn't mean "The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth, " which has always seemed to me an exercise in self-parody. The best enhancements to this volume probably would have come from the UK magazines, particularly Science Fantasy, which are not represented on the Nebula list: Aldiss's "Man in His Time," in particular.

Beauclerk's stuff is interesting. Not exactly brilliant, but with a certain allure.

I'm glad someone else feels the same way about that particular Zelazny. I feel like he runs hot and cold while others think he only runs hot.

Above comment is mine.

@ John B (mostly) —

I think Zelazny's 'He Who Shapes' (his Nebula novella winner) is one of the best things that he's done, along with his 'The Graveyard Heart' a couple of years back. In both cases, he set out to write real science-fiction set in a near-future, rather than relying on the myth and fantasy props, and I'd prefer it if he did more of this kind of work as opposed to 'Doors of His Face, etc.'

Though I like the cartoon Hemingway aspect of that more than you do — self-parodic or not, the prose moves right along and shows some flair, which SF is in dire need of ….

To hell with it: I'm going to set aside the pretense that we're all living in 1966 for a moment, if you'll forgive me ….

Looking back from the 21st century, Damon Knight's anthology NEBULA AWARD STORIES 1965 was a book that had a strong role in making me an SF reader when I was a kid, and besides the Zelazny stories — and it's hard to grasp now how much of a great new thing and breath of fresh air he seemed when he emerged in the 1960s — Knight stuck in a story by J.G. Ballard, 'The Drowned Giant' from 1964 for no reason except that he wanted to, alongside Schmitz's 'Balanced Ecology' and Aldiss's 'The Saliva Tree.'

So my memory of that particular anthology by Knight, with his choice of what else he put in it, was mainly what prompted me to bring up the Nebula award winners of that year in comparison to Wollheim-Carr's choices. In subsequent historical reality, of course, Zelazny went down the Amber fantasy tubes mostly, and ceased to be much a science fiction writer at all, except for 'Home Is the Hangman' and its companion stories in the 1970s. Nevertheless, it's hard now to overstate the feeling in the 1960s that he and Delany were making American SF into this new, blazingly better thing. And like I say, between that, and the Ballard — one of Ballard's best — and the others, in general the stories in Knight's Nebula anthology show heaps more flair than the Wollheim-Carr.

Yes to the substitution of Lafferty's 'Slow Tuesday Night' for his 'In Our Block.

As for the lack of women in both the Nebula list and the Wollheim-Carr, I don't know what editors were seeing in their slush piles then. But in terms of what actually reached print in the magazines, there were few female writers : there'd been a few early Kate Wilhelm stories, a very few Joanna Russ and Ursula Le Guin stories, and Anne MacCaffrey (blech) and Marion Zimmer Bradley (also blech). Give it a few more years and, as Algis Budrys pointed out, all the top SF writers were women.

I think we would probably all agree that the Nebula Awards volume was a better anthology than Wollheim/Carr. Meanwhile, there's Judith Merril to look forward to in December.