by Gideon Marcus

Casualty of War

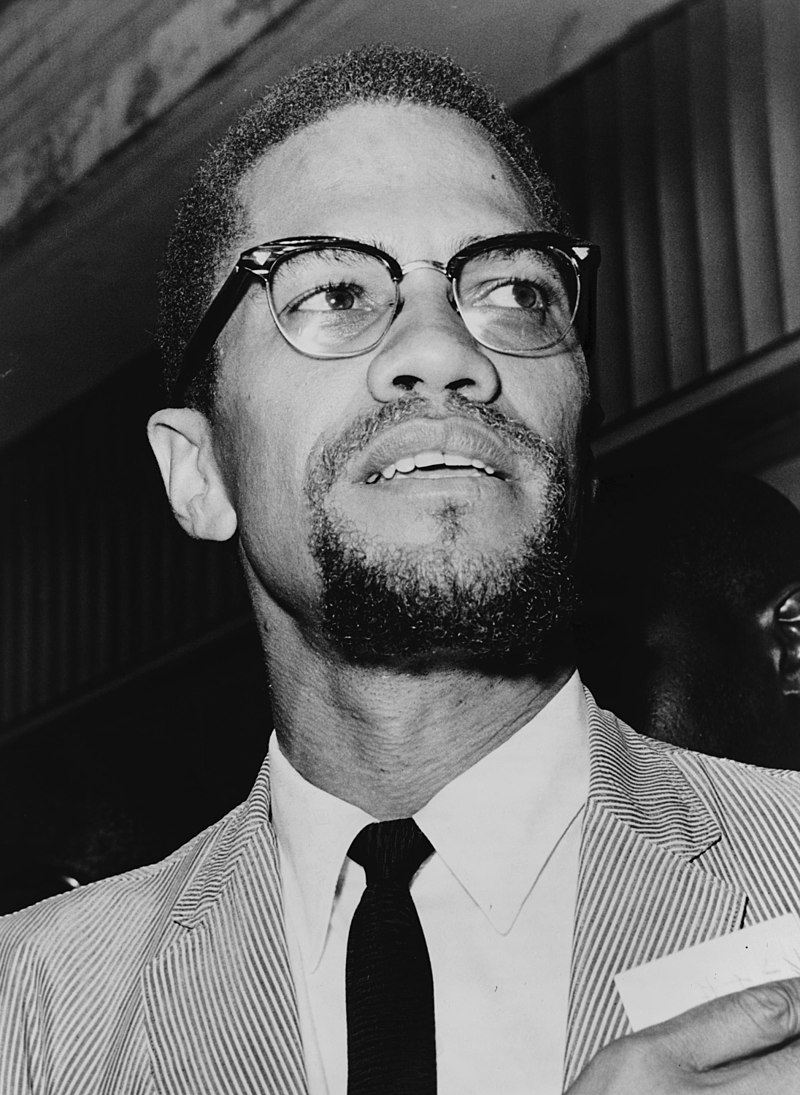

Malcolm X was shot on my birthday.

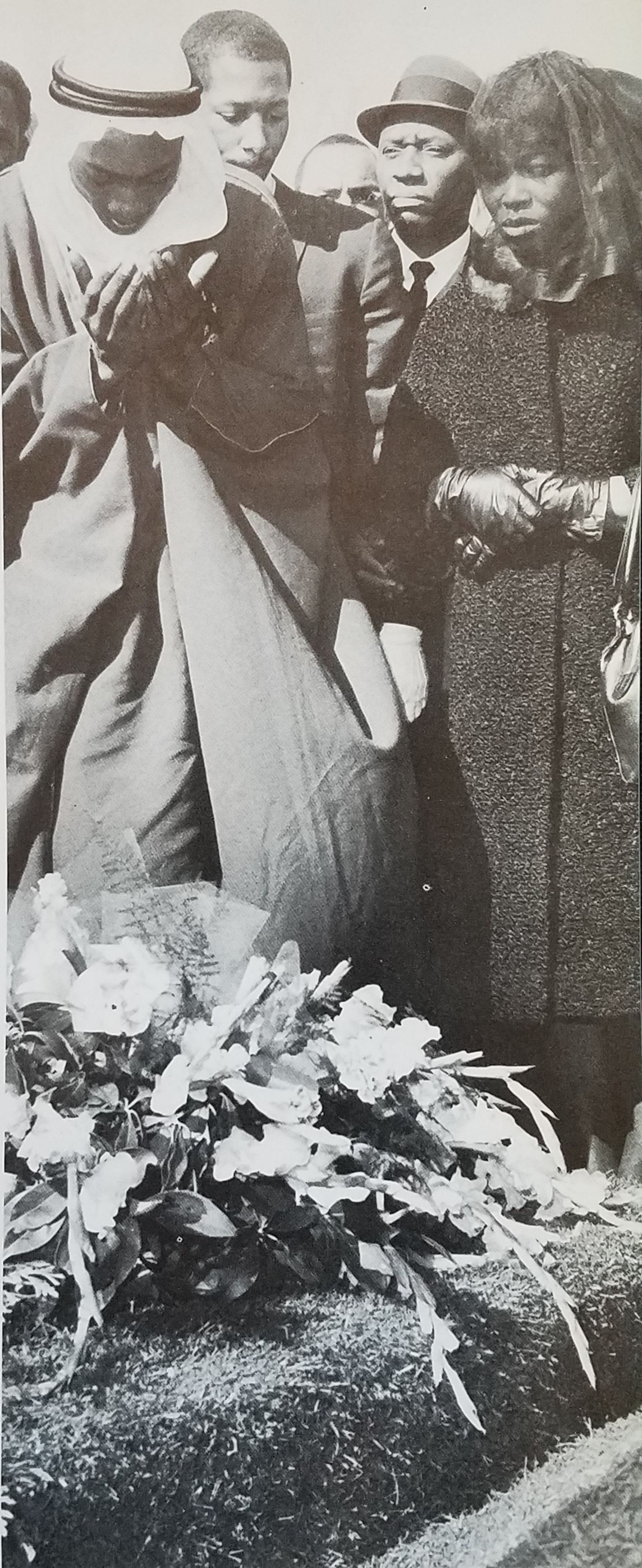

While I was celebrating with friends on February 21, 1965, enjoying cake and camaraderie at a small Los Angeles fan convention, Malcolm X, one of the highest profile fighters for civil rights in America, was gunned down. At a meeting of the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), a group X founded, three shooters attacked the 39-year-old father of four (soon to be five), wounding him sixteen times. He did not survive the trip to the hospital.

Two of the assailants were captured, but their motive is still unclear. All fingers point to the Black Muslims, however. After his disillusionment with and fraught departure from the group, X had cause to worry that they intended to rub out a man they thought of as a traitor. Indeed, X had received a number of death threats prior to the OAAU meeting.

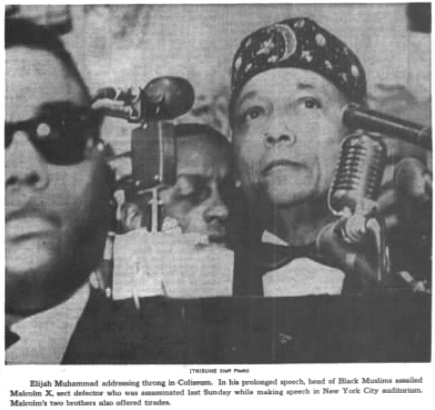

Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Black Muslims, had to arrive at a rally at New York's Coliseum on February 26 flanked by police protection. Addressing the large audience, he made clear that he'd come to savage X, not to praise or bury him.

Malcolm X was a controversial figure. Whereas Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s non-violent methods have earned him almost universal admiration from America (those who fight the old order, anyway), X was a militant Afro-American. It was only recently that his attitude toward Whites began to soften, the result of a pilgrimage to Mecca, which he shared with many light-skinned Muslims. Nevertheless, there is no question that the war for civil rights has claimed one of its most important generals.

As Black Americans prepare for a freedom march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, the cynic in me wonders who will be next.

Cheering News

In recent months, that kind of a downer headline would segue easily, if dishearteningly, into a piece on how the latest Analog was a disappointment. Thankfully, the magazine is on an upswing, and the March 1965 Analog, last of the "bedsheet" sized isues, is one of the best in a long while.

by John Schoenherr

The Twenty Lost Years of Solid-State Physics, by Theodore L. Thomas

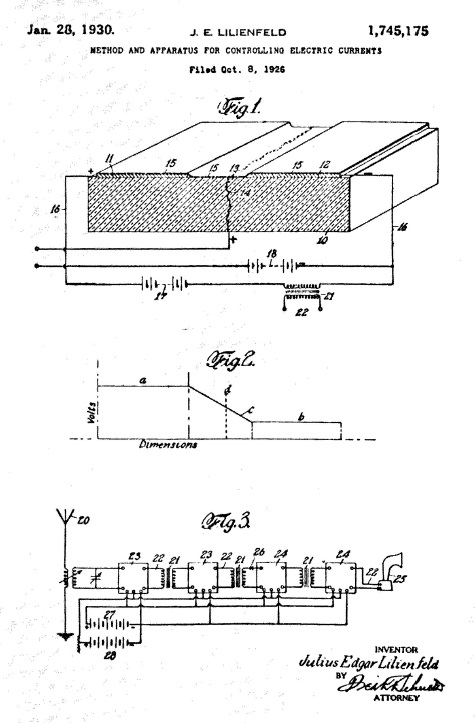

Theodore L. Thomas takes a break from his rather lousy F&SF science vignettes to talk about the patenting of the first transistor. Apparently, a fellow named Lilienfeld worked out the theory long before Shockley et. al., filing a patent as early as 1930! Yet, Lilienfeld never tried to build the thing, and the invention had no effect on the world save for complicating the filing of later patents by others. Sad, to be sure, although Lilienfeld had a prolific career otherwise, and I'm given to understand that materials technology was not sufficiently advanced to make the device back then anyway.

Still, it makes you wonder what other inventions lie buried at the patent office, lacking a vital something to bring them into common use.

Four stars.

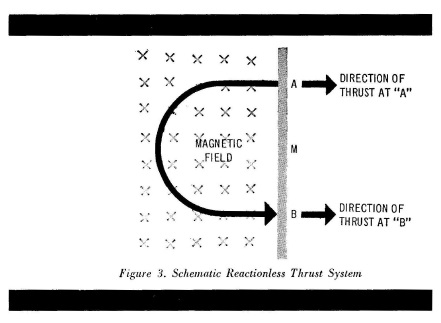

The Case of the Paradoxical Invention, by Richard P. McKenna

Speaking of inventions that haven't found their era, McKenna offers up a motor powered by the stream of radioactive particles from a decaying source. The problem is, it appears to be both physically possible and impossible simultaneously.

The math is over my head, and probably over the head of most of Analog's readers, too.

Two stars.

The Iceman Goeth, by J. T. McIntosh

by Leo Summers

Andrew Coe is an iceman. Years ago, he had his emotions wiped clean, both punishment and societal protection, for Coe had murdered an ex-lover for unfaithfulness. Now he makes a living with a clairvoyant and telepathy act — except it's no act. He's the real deal.

It appears nothing will change the colorless unending cycle of work and sleep, but outside Coe's harshly circumscribed life, the city he resides in is slowly going mad. Psychotic breaks followed by motive-less murders and suicides have been steadily on the rise. The police are at wits end as to their cause until a scientists pinpoints their origin to an unexploded dementia bomb, dropped in a war 50 years before.

To find the thing, Coe will have to have to use his full mental powers, only accessible if he gets back his emotions.

There is a five star story here, one where the drama resides in the decision to restore Coe to his former self. Coe is a killer; is it worth it unleash one madman on the world to stop a hundred?

The problem is, that's not how McIntosh plays it. Instead, Coe simply finds the bomb, receives a pardon, gets a new girl, and everyone lives happily ever after. No mention is made of his past crimes. We never learn about the woman he killed. If anything, McIntosh almost seems to excuse Coe's act as forgivable given the circumstances.

Deeply dissatisfying, but God, what potential. Three stars.

(Have we seen this concept of the iceman before? It seems awfully familiar.)

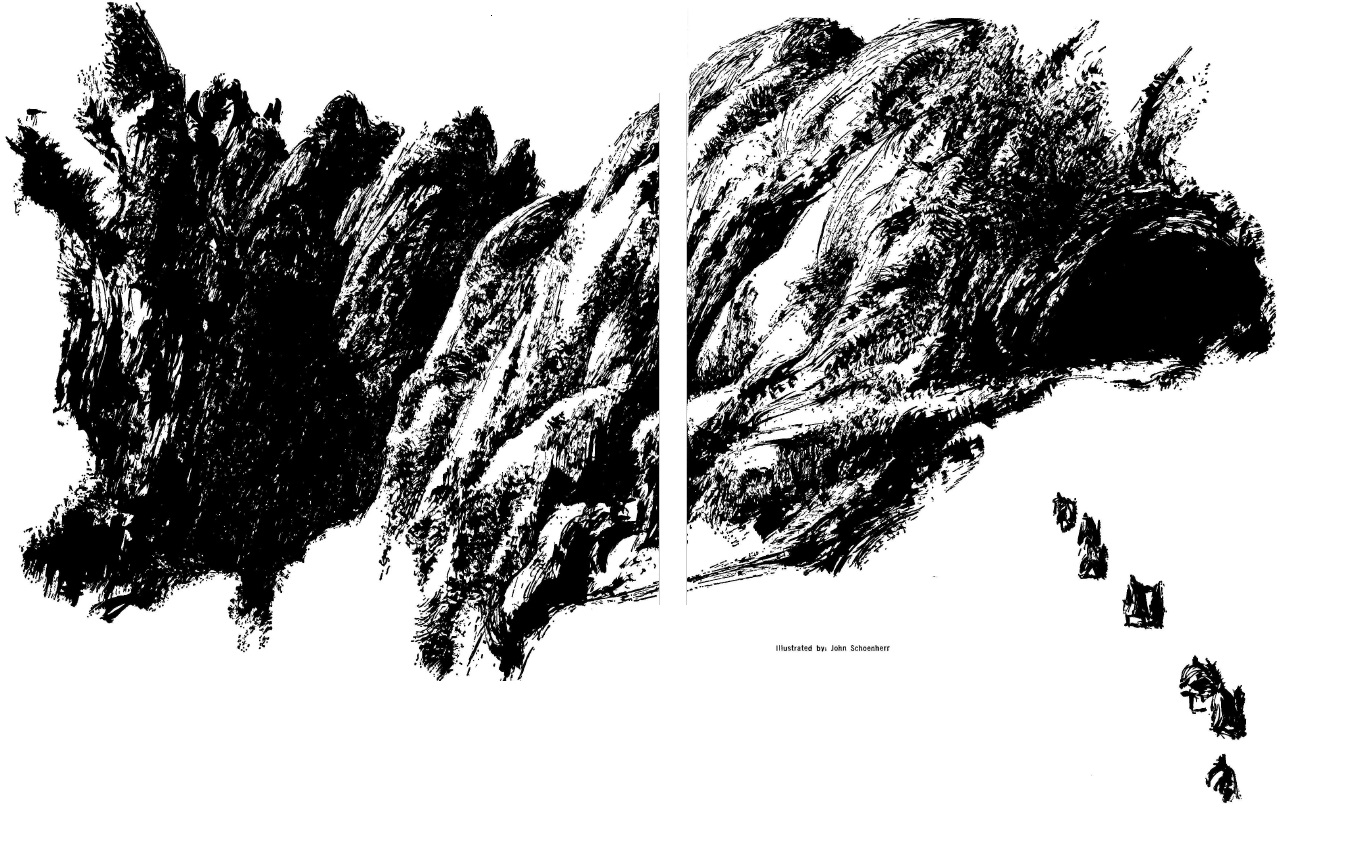

Balanced Ecology, by James H. Schmitz

by Dean West

The McIntosh is followed by a tale as delightful as the prior story was disappointing. On the planet Wrake, the ecosystem is uniquely interdependent. Among the groves of diamondwood trees reside the skulking slurps, whose primary prey are the ambulatory tumbleweeds, whose seeds are tilled by the subterranean and invisible "clean-up squad". Other denizens are the monkey-like humbugs, with an annoying tendency to mockingbird human expressions, and the giant tortoise-like mossbacks, who sleep for years at a time in the center of the forests.

Ilf and Auris Cholm are pre-teen owners of one of these woods, heir to a modest fortune thanks to their well-moderated timbering operation. When greedy off-worlders want to effect a hostile takeover for a clearcutting scheme, do a pair of kids stand a chance? Not without a little help, as it turns out…

I really really liked this story, almost an ecological fable. The only bumpy spot, I felt, was the part where the villain revealed his evil scheme in a bit too much of a stereotypical, if metaphorical, cackle.

Four stars.

The Wrong House, by Max Gunther

by Adolph Brotman

Out in the suburbs, they're building giant subdivisions with rows of handsome houses on gently curving lanes. Many find them charming, but others find them unsettling — like the young woman who confesses (in The Wrong House) to her engineer husband that her home seems somehow "unfriendly." To his credit, the man takes his spouse seriously and determines to understand why the air duct pipe is warm instead of cool, and just what all those strange electronics installed in their attic might be…

Another good story, maybe a little too pat, but well executed. Four stars.

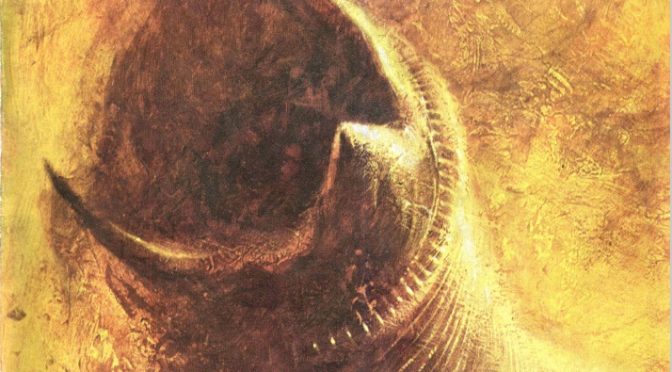

The Prophet of Dune (Part 3 of 5), by Frank Herbert

by John Schoenherr

Now we come to the centerpiece of the issue, the sweeping serial scheduled across the first five months of 1965. In this latest installment, Paul Atreides and his mother, the Bene Gesserit Lady Jessica, fulfill prophecy and become spiritual leaders of the Fremen, the indigenes of the desert planet Arrakis. Meanwhile, Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, usurper of the Atreides fiefdom on Arrakis, schemes to parlay his control of the geriatric spice melange into rulership of the entire galactic Empire.

There were times when the immense scope and obvious attention to detail threatened to elevate Dune into four star, even classic territory. And then Frank Herbert's fat fingers got in their own way and gave us such classic passages as this:

Paul heard hushed voices come down the line: "It's true then–Liet is dead."

Liet, Paul thought. Then: Chani, daughter of Liet. The pieces fell together in his mind. Liet was the Fremen name of the Planetologist, Kynes.

Paul looked at Farok, asked: "Is it the Liet known as Kynes?"

"There is only one Liet," Farok said.

Paul turned, stared at the robed back of a Fremen in front of him. Then Liet-Kynes is dead, he thought.

I guess Kynes is dead. He's also called Liet. I thought.

How about this one:

"This" — [Baron Harkonnen] gestured at the evidence of the struggle in the bed-chamber–"was foolishness. I do not reward foolishness."

Get to the point, you old fool! Feyd-Ruatha thought.

"You think of me as an old fool," the Baron said. "I must dissuade you of that."

Fool me thrice, shame on Herbert. The third-person omniscient/everywhere/everyone vantage is clumsy; a better writer could go without such exposition and switching of viewpoints, instead saving it, perhaps, for the times when Paul goes into one of his prescient fugues.

But I do want to keep reading, if for nothing else than to know what happens.

Three stars.

Desiderata, by Max Ehrmann

For some reason, Analog's editor, John W. Campbell Jr., decided to include a set of homilies from the inside of Old Saint Paul's Church in Baltimore, dated 1692. At first, my atheistic side bridled, but I ultimately found the platitudes refreshing and timeless.

No stars for this entry, for it's not really a tale nor an article.

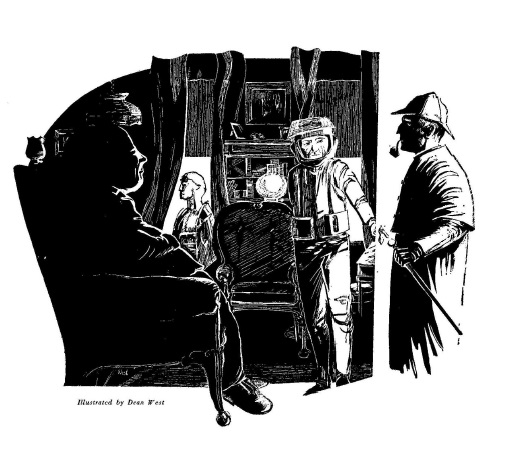

The Legend of Ernie Deacon, by William F. Temple

by Dean West

Last up, we follow the exploits of Arthur, captain of a two-place merchant ship plying the lanes between Earth and Alpha Centauri. It's a twelve year trip, reduced to a subjective 18 months thanks to time dilation. It's still a long time, but Art finds it lucrative and satisfying, trading full-sense movies called "Teo's" for the life-saving medicine, varos. Legend is a philosophical piece, discussing the morality of preferring a vicarious life to a "real" one (and of facilitating the addiction thereto), and also evaluating the reality of fictional creations whose existence comes to shadow that of their creators (e.g. Holmes over Doyle).

Good, thoughtful stuff, with an ending that can be viewed as mystical or simply sentimental.

Four stars.

Summing Up

The counter to tragedy is hope, and the latest Analog gives me a lot of hope — that the magazine that ushered in the Golden Age of science fiction will rise to former glory (some may argue that the magazine never fell; it has maintained the highest SF circulation rates for decades.) In fact, Analog is the month's highest-rated mag, at 3.3 stars, for the first time in years.

Fantastic followed closely at 3.2; all the rest of the mags were under water:

Amazing and New Worlds both merited 2.9 stars (but the former made John Boston smile, so that's something). Science-Fantasy scored a sad 2.6. Fantasy and Science Fiction was a lousy 2.3. IF, at 2 stars, was so bad that I'm not sorry to stop reviewing it; that harsh task now falls on the shoulders of one David Levinson, whom we shall meet next month.

And February does end with one more bit of tragedy: out of 45 fictional pieces published in magazines this month, only one was written by a woman.

Here's hoping March offers better news on that front, and others.

An *ahem* astoundingly good issue for what Analog has become. Even the editorial, discussing the whys and wherefores of first adopting and now abandoning the slick format, was pretty good. Surprising what Campbell can write when he isn't ranting or playing devil's advocate (though if you agree with the devil, are you just playing?).

Ted Thomas' article was interesting and does make one wonder about ideas whose time hasn't come yet. Alas, it's also the sort of thing that plays into and props up Campbell's special brand of crackpottery.

The other fact article was utterly beyond me. I wonder if it isn't a bit beyond the author as well. I'm sure there's a fairly obvious error or misunderstanding in there somewhere.

"Iceman" started out so well. Really, it was fairly decent right up until the last page or so. Even MacIntosh ought to have been able to bring this up to four stars. A decent editor might have gotten him there, too.

The Schmitz was delightful. Is there anybody who writes children better? Zenna Henderson does pretty well, but we see her children from the outside through the eyes of, usually, teachers. Schmitz's children are viewpoint characters and we see inside their heads. And they are very believable.

"The Wrong House" was an interesting take on the idea of a house feeling "off". I don't think I've ever lived anywhere where there wasn't some room or corner of the garden that I mostly ignored and avoided as much as possible. I'm not sure I could go all the way to four stars, but that's mostly a function of why the house actually was wrong.

Your problems with "Prophet of Dune" are real, but they really come down to editing, don't they? What you're saying is that with a bit of editing (especially line editing in your examples) this would be a classic. It's really just another example of why Campbell has to go. And say whatever you like about this and the previous story, but Schoenherr's cover is justification for them all by itself. That thing is a masterpiece and he deserves a Hugo for it.

"Ernie Deacon" was pretty good, and an odd fit for Analog. Again, not sure I could give it that fourth star, but a solid 3+ certainly.

There's no question Schoenherr has landed — I chose him for the Galactic Star last year, and not a little for his work on Dune.

I suppose I could talk more about the art, but I feel it speaks for itself. Jack's a good'n.

I also agree that, of all the stories I gave 4 stars to, the Schmitz is the best. I wavered between 4 and 5, honestly.

I didn't yet get around to reading this issue, but that awesome cover actually makes me look forward to The Prophet of Dune.

Love Gunther's 'The Wrong House'! Original, too.

Sand + PSI = crowd goes wild.

"The Iceman Goeth" was OK, I guess, but I never believed any of it. Maybe it was the way that so many premises got mixed together. And that business with the War Department bureaucrat seemed pointless. (The big problem, of course, is that the "hero" is a convicted murderer! Given his crime of passion, I wouldn't want to be his new wife!)

"Balanced Ecology" was a fine piece of world-building, even if the villains were over-the-top evil. Definitely the highlight of the issue.

"The Wrong House" was, well, interesting. More appeal to the mind than the heart.

"The Legend of Ernie Deacon" was the exact opposite. As such, it was an effective piece.

Lilienfeld's transistor: He certainly did build these. Bell Labs' Pearson secretly tested it, publishing their paper in Physical Review for July 15 1948, the same journal where their point-contact transistor was announced …but wo/referencing Lilienfeld at all! In science this is utterly dishonest. Never forget that Bell Labs was a business first, scientists only a distant second.

Lilienfeld was showing around a 4-transistor radio in the 1930s, to no effect. Others have theorized that the main reason for his rejection (besides the Gernsback-Cambellian trope of science' immense resistance to new ideas,) was the fact that Lilienfeld was Jewish in a time of bigotry. (Yet Texas Instruments also initially encountered the same odd barrier.) Lilienfeld then gave up on the USA, took his existing fortune and moved to the Caribbean. Lilienfeld was wealthy, having invented the modern electrolytic capacitor.

Where did the rumor get started that Lilienfeld (an experimentalist) hadn't bothered to build any transistors? No rumor, instead JB Johnson of Bell Labs insisted! Decades later it was exposed that JB Johnson actually had seen these transistors work when Shockley and Pearson built copies, describing this in a legal deposition, only later vocally denying the fact. All the Bell transistor patents at the time were being rejected because of Lilienfeld's prior art. Bell Labs was trying to make profitable FETs, and had secretly succeeded, but couldn't own them. Yet wouldn't such information would make Bell Labs look very bad, had it all come out at the time? The point-contact transistor was only an ingenious work-around, a patentable discovery, and today falling by the wayside, with FETs taking over.

Besides that dishonest 1948 research paper, Johnson specifically lied to Dr. Bottom, spreading the false idea that Lilienfeld had failed, or was even too stupid to follow his own detailed instructions from his patents, and besides, Lilienfeld's transistors couldn't work in theory, eh? (mysteriously avoiding having Bottom find out that they work just fine in practice!)

R. G. Arns says that Bret Crawford built sucessful Lilienfeld transistors in 1991 as his MS Physics Thesis. Joel Ross did it again in 1995 with more stable versions. He then discovered Bell Labs' mendacity, see: RG Arns, early transistor history https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/730824?arnumber=730824&isnumber=15787&punumber=2222&k2dockey=730824@ieejrns&query=((arns)%3Cin%3Eau%20)&pos=3&access=no

http://web.archive.org/web/20060301093157/chem.ch.huji.ac.il/~eugeniik/history/lilienfeld.htm

– “Lilienfeld demonstrated his remarkable tubeless radio receiver on many occasions, but God help a fellow who at that time threatened the reign of the tube.” – HE Stockman, Sercolab Inc. Lowell MA, letter to EWW magazine 1981

Where giant corporations and fabulously enormous amounts of money are involved, conspiracy theories may actually be the rule, rather than the exception? Heh. One shouldn't be that surprised!