by Gideon Marcus

Recycling is good practice

We are now three weeks into the second season, and Star Trek continues to impress. If the season premiere was an episode that could only have existed in the Star Trek universe, last week's and this week's are back to the first season formula of adapted, universal science fiction tales. Nevertheless, "The Changeling" is a uniquely Trek episode, adding to the depth of the setting and capitalizing on what we know of the characters.

Checking in on the Melurian system, the Enterprise finds that something has wiped out its four billion inhabitants. Said something then begins shooting at the Enterprise with bolts possessing the power of a whopping 90 photon torpedoes (the fact that the shields can withstand four such hits suggest either the torps are weak sauce or the assailant was at the edge of its range). After firing on the enemy, Kirk attempts communication; that Kirk didn't try talking first is not inconsistent with his character; he's "a soldier, not a diplomat."

The hail works. The assailant, barely more than a meter in length, consents to being beamed aboard the Enterprise. There, it is quickly determined that it is what is left of the 21st Century deep space probe "Nomad", and it thinks Kirk is its creator, Jackson Roy Kirk (perhaps a distant ancestor?)

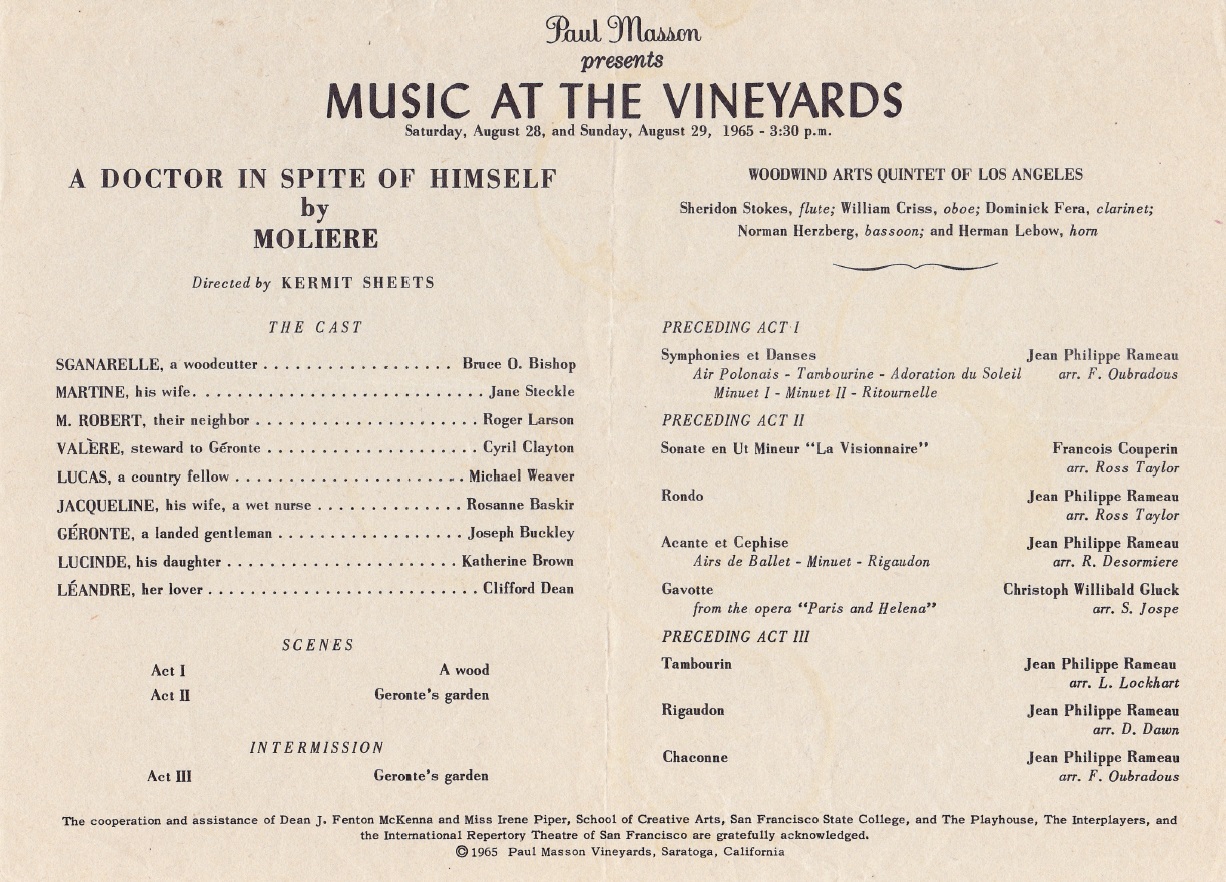

Nomad is now more than just the next iteration of Mariner spacecraft. After a collision and merging with the alien probe, Tan Ru, it is now an intelligent, self-aware being with just two motivations: "To seek out and sterilize all that which is not perfect" and to impress his creator, "The Kirk." Nomad “fixes” the Enterprise so it can go Warp 11, popping all of the Enterprise's rivets. It kills Scotty, then brings him back to life.

More chillingly, it zaps four security guards out of existence (to be fair, they fired first). It gives Uhura a kind of stroke, temporarily cutting her off from her advanced knowledge. And when Kirk concedes that he is an imperfect biological unit, Nomad resolves to go back home to Earth–and wipe out all imperfection. He is only stopped when Kirk, in "a dazzling display of logic", makes Nomad aware of its own imperfections, ordering it to self-destruct, which it does.

There's nothing in this episode we haven't seen or heard before. The naive, all-powerful presence taken aboard the Enterprise, kept in check solely by a tenuous parent-worship of Captain Kirk, is the same plot as "Charlie X". Kirk already defeated a computer with logic in "Return of the Archons." All of the action takes place on the Enterprise, and much of the music is recycled from the prior two episodes.

And yet, this may be my favorite episode of the season thus far. Not only do we learn some interesting things about Terran history (we now have a tentative timeline – from the Eugenics Wars of the 1990s to the first warp-powered probes of the early 21st Century), but the episode depends in large part on things that have already been established about the characters we've come to love.

I love this show of Sulu jerking back as Nomad flies right past him to ask what the heck Uhura's doing

Nomad is intrigued by Uhura because of her singing, and we get to see her speaking Swahili again, too. Scotty gets himself killed defending her (we learned last episode that Scotty's brain short circuits where women are concerned). Spock uses his mind-touch on Nomad (and aren't there all kinds of interesting ramifications from that). Kirk is better than ever at beating computers–his defeat of Nomad was far more logical and satisfying than his victory over Landru.

I found Kirk's performance more understated this episode, which I appreciated, and Nimoy was excellent as usual. I also appreciated the return to a more ensemble approach, with heavy focus on Uhura, Chapel, Scotty, and McCoy. If there was only one bobble in tone, it was Kirk's (admittedly funny) line about lamenting the loss of Nomad, his son, the doctor. Given the loss of four billion Melurians and four of his crew, one would think Kirk would be a touch more somber.

Those are quibbles, though. Four stars.

The Truth will set you free

by Joe Reid

I find large numbers to be amazing things. We as human beings have developed ways to express and manipulate numbers that are vaster than we have the ability to conceive of. I myself can mentally picture 10 bowling pins, 100 sheets of typing paper, and a jar of 1000 pennies. Ten thousand, one hundred thousand, and even one million are numbers that inspire awe. How about four billion? Imagine you line up everyone on earth, you would be 500 million short of four billion! This week’s episode of Star Trek left me with a question that needs to be answered. How do you kill four billion people?

I don't mean the physical means by which he brought this about. Each of Nomad's bolts packs a 90-photon torpedo wallop. I mean how does Nomad, an intelligent thinking machine, kill four billion people? I look at Star Trek as a mirror being held up to the audience. With the writers holding up that mirror and saying, “This is what we look like.” Therefore, the question also is, how do we as intelligent thinking beings kill hundreds, thousands, and even millions of people? The answer to both questions is the same. You believe a lie.

Nomad believed that it was perfect. That its creator was perfect. That the mission in its memory tapes were perfect. Nomad took that belief as a given. So, anything that didn’t fit within its own understanding should be wiped clean. We saw this when Nomad encountered a singing Uhura and erased her mind. Since Nomad was perfect any action it took was ultimately justifiable, so any resistance to it should be eliminated, which was the case of the four guards and Scotty. All of which died. Along the same lines, any being that does not meet his level of perfection is an infestation which must be eliminated. We were told about four billion examples of that, with the promise of more to come.

The price of imperfection.

By Nomad’s actions we see our own human condition. When we believe the lie that we are better than those around us, that those who are not like us are below us, we find justification to ignore them. Those who we can’t ignore we remove. Those we don’t understand or agree with we erase. Those not like you are not human, so killing them is justified, because those “things” are a useless infestation. My friends, we believe such lies and commit these acts upon other humans.

In the end, Nomad was undone by the truth. When it learned the truth that it was not perfect, Nomad stayed consistent with its other beliefs and ended its own existence. How do humans respond when they are exposed to the truth? Perhaps a future episode of Star Trek will provide that answer. I cannot. Since like you, I am afflicted with my own deck of lies that guide my own beliefs.

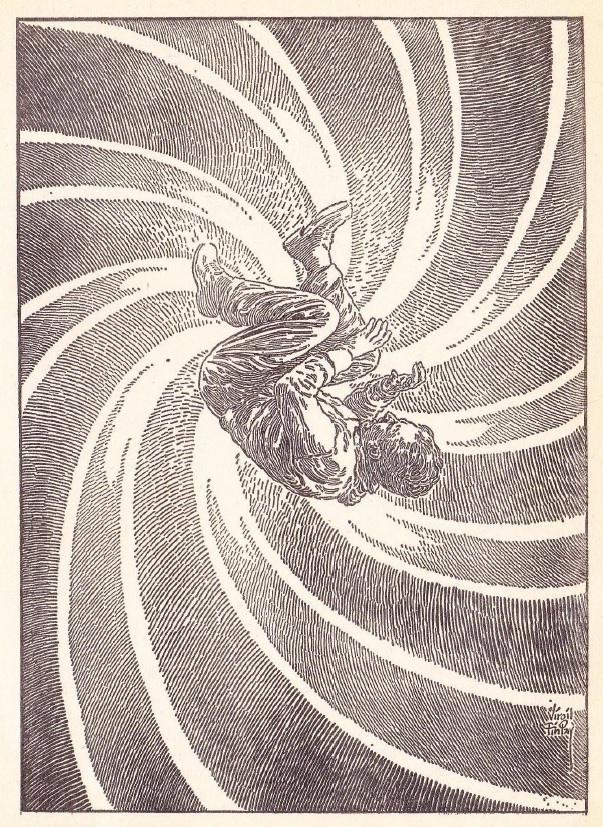

Nomad learns the truth.

Overall, this was another exciting and thought-provoking episode which makes my Thursday nights most enjoyable. Not perfect by any means, but a worthy addition to this wonderful program.

4 stars

"The Nomad who Wandered Got Lost"

by Amber Dubin

As a self-confessed robot-a-phile, I felt the need to take a second pass at this episode to fully understand its protagonist. After listening to the audio tapes I made of the episode, I found that the understanding I gained left me unsettled.

The concept I found most disconcerting is that, despite the fact that it wiped out an entire solar system's worth of people, to hate Nomad would be as unreasonable as hating a child. Though it is powerful, ancient, sophisticated, and sentient to boot, Nomad is frequently compared to a child. The fact that this episode is called "The Changeling" implies that it is a lost child robbed of its intended destiny. Much like a child whose birth kills its mother, it gains sentience by being cruelly ripped from the void, forced to survive the trauma of its birth while destroying the only witness to its initiation of life. To assuage its survivor's guilt after the entanglement with the alien probe, it seeks to validate its existence with the hastily slapped together objectives from the partial data stores of two damaged probes, with predictably disastrous results. It may kill people, but only in the way a Changeling child might if given immense power and no moral guidance.

Inside the mind of a child

The other concept that left me with "insufficient data to resolve problem" was how easily Nomad was compelled to merge two peaceful objectives into one murderous one. In Spock’s words, "Nomad was a thinking machine, the best that could be engineered" and yet that same intellect made it unable to live up to its own standards. In trying to explain its sentience in a literal vacuum, it uses its 'perfection' to explain why a lowly soil sterilization probe was sacrificed to preserve its function. In honoring that sacrifice by incorporating "the other's" programming, it is then faced with the impossible task of applying a local objective onto a global scale. To make its task more manageable, it translates 'sterilize your environment' to "sterilize imperfections." This way, it avoids failing its objective and admitting that its pursuit of perfection is internally flawed. When Kirk exposes this flaw, Nomad's inability to reconcile it was probably the most human reaction I've ever seen. I tip my hat to the kind of writing that could make me wonder if self-destruction is in the nature of an inquisitive mind.

This episode lost points, however, when it came to Uhura's subplot. I initially had a visceral reaction to her re-training scene. The way they talk to her while teaching her to read is not the way you talk to a stroke victim re-learning language, it's how you speak to a child learning language for the first time. I bristled at the nurse's condescending praise and saw it as an insult to Uhura’s intelligence. Listening through the second time, however, softened my perspective. By including Uhura’s outburst in Swahili, and the nurse's comment that Uhura "seems to have an aptitude for mathematics," it was apparent that there was most likely no malicious agenda to make Nichols look stupid. More than likely the purpose of the scene was to say 'Gee English sure is a silly language.' While not being as offensive as I originally thought, it's still disappointing and doesn't hold up to the standard set by the writing of the rest of the episode (strong enough to still get four stars).

"Who wrote this scene, anyway?!"

The next episode of Trek is TONIGHT! It doesn't look like we're in Kansas anymore…

Here's an invitation. Come join us!

![[October 6, 1967] Deus ex Machina (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Changeling")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671006title-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1967] Switching Sides (November 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/IF-1967-11-Cover-672x372.jpg)

The logo for the traffic changeover.

The logo for the traffic changeover. This photo was staged several months ago as part of the education campaign. The real thing was much less chaotic.

This photo was staged several months ago as part of the education campaign. The real thing was much less chaotic. A newcomer gets the cover. Does he deserve it? Art by Vaughn Bodé

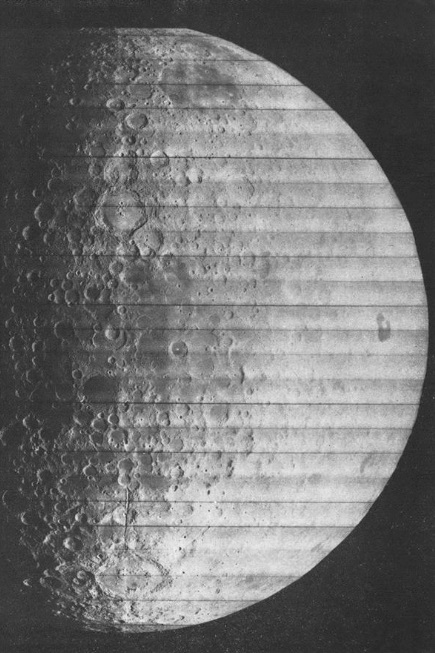

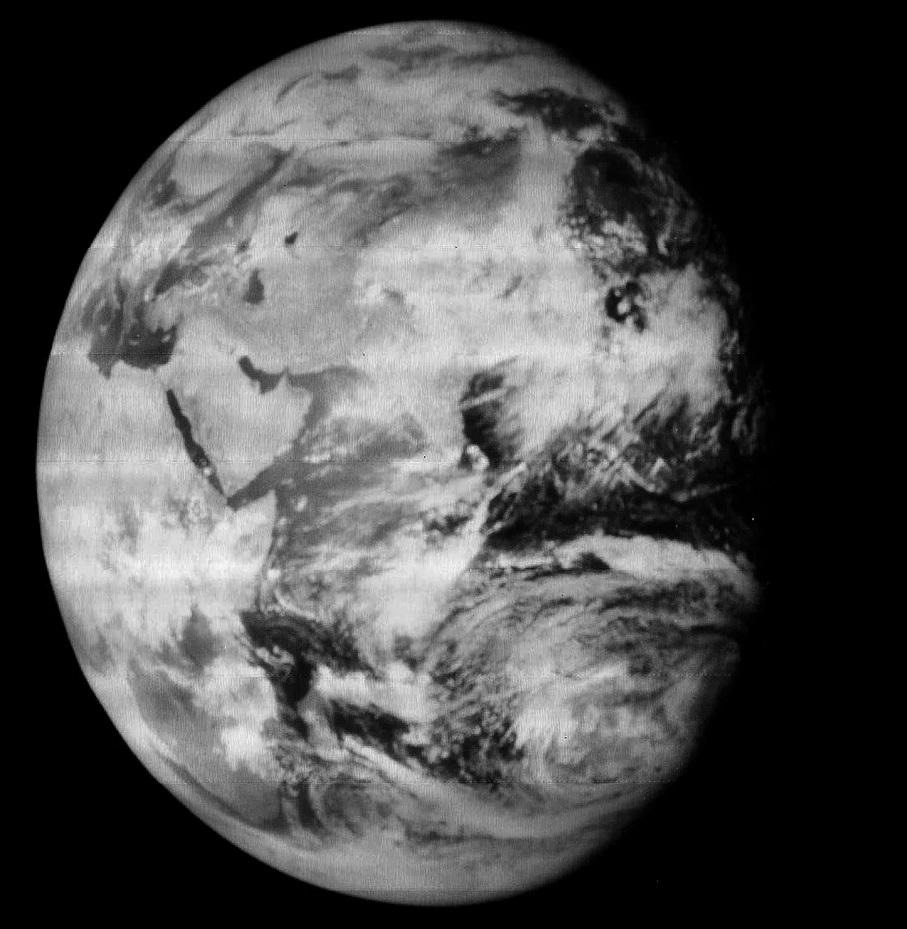

A newcomer gets the cover. Does he deserve it? Art by Vaughn Bodé![[August 24, 1967] Up and Around (Lunar Orbiter)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670824lunarorbiter-672x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1967] Family lines (August 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670710cover-672x372.jpg)

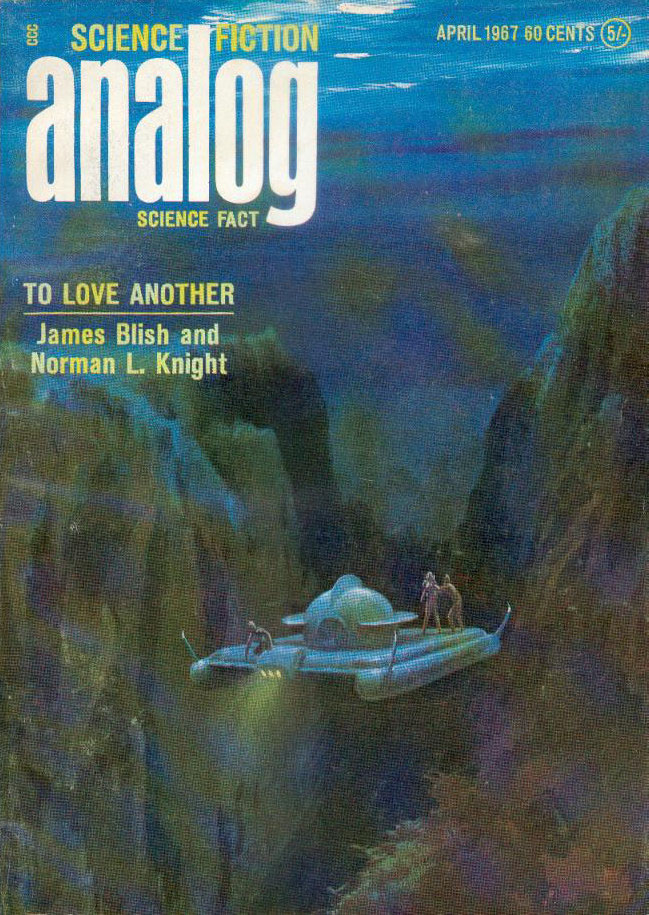

![[March 28, 1967] At last, a drop to drink (April 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670328cover-649x372.jpg)

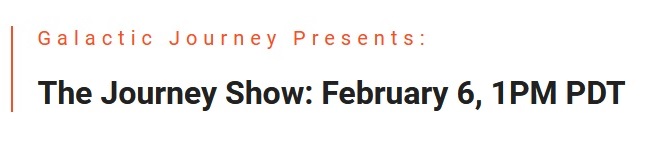

![[September 4, 1965] Doctor's Orders (Review of "A Doctor in Spite of Himself")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Moliere.jpg)

![[January 16, 1965] What a Difference a Year Makes (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Season 2, Episodes 13-17)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650116end-672x372.jpg)

![[May 28, 1964] Down to the Wire (<i>Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 29-32)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640528e-672x372.jpg)