by Gideon Marcus

The Winds of Change

History is divided into eras: The Stone Age, The Middle Ages, The Renaissance. There are Golden Ages and Dark Ages. The Jazz Age. The Gilded Age. One is never quite sure of a period's exact delineations, the precise moments of its beginning or end, until the next one is well on its way. It is possible to tell when one is in an age, however, and also to feel keenly the wistful uncertain sense one gets in the doldrums between epochs. Who can't have felt that way in the year succeeding President Kennedy's assassination, when his civil rights program, American involvement in Indochina, even the character of government in general hung in the balance. And who can doubt that, for better or worse, the Johnson era has clearly begun?

I've lived through two sea changes in music. The first was in 1954, when the overripe swing and schmaltz on the radio was overrun with a wave of rock and roll, particularly if you tuned into the Black stations (luckily, a radio tuner cannot easily be segregated). By 1963, the winds of change had become muddled. With folk, pop, motown, surf, and country vying for our eardrums, it was quite impossible to know then where the next two years would take us. Then the Beatles spearheaded the biggest British invasion since 1812, and a new age was upon us.

Science fiction has its ages, too. When I got into SF in a big way, the genre was clearly plumb in the middle of one. It was 1954, four years after Galaxy's editor, Horace Gold, had thrown the gauntlet down at the feet of puerile pulp SF, five years after the new Fantasy and Science Fiction established a literary benchmark for the genre that has yet to be exceeded. Science fiction primarily came in digest sized magazines, and the market was aflood with them. Quality ranged from the penny-a-word mags which were little above the pulps that preceded them to stellar new fiction that burst beyond our solar system and ranged deep into our pysches.

As the 60s dawned, the genre had become anemic. Almost all of the monthly digests had gone out of print. The old stalwart, Astounding, had changed its name to Analog, but is fiction remained stolidly fixed in an older mode. Gold retired from Galaxy and Fred Pohl struggled to keep it and its sister mags fresh as its reliable stable of authors left for greener (as in the color of money) pastures. F&SF's helm passed on to Avram Davidson, whose whimsical style did the magazine few favors.

But the genre seems to have found its feet and is stomping off in a new direction. Propelled by a "New Wave," again largely based in Britain, the science fiction I've been reading these days no longer feels like retreads of familiar stories. They have the stamp of a modern era, an indisputable sense of 1960s. And no single issue of a single magazine has represented this renaissance in SF better than the latest issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

A Fresh Breeze

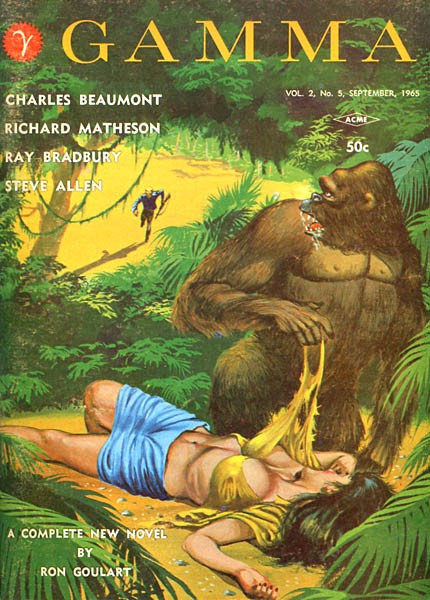

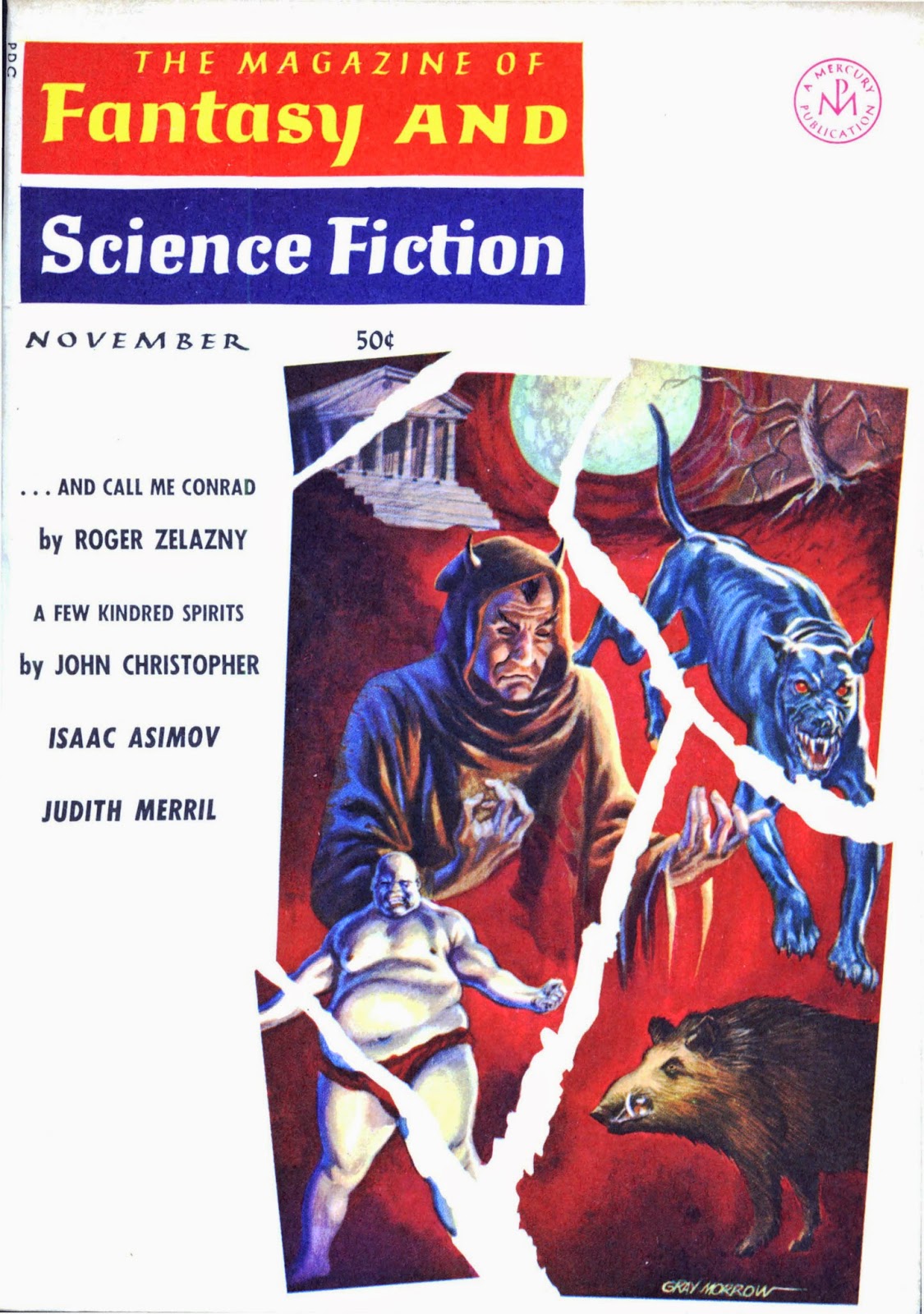

by Gray Morrow (illustrating the many perils of … And Call Me Conrad (Part 2 of 2)

Come to Venus Melancholy, by Thomas M. Disch

Disch is one of the flagbearers of the new era. In just three years, this new author has produced more than 20 stories, some of them quite brilliant. In this one (set on an obviously pre-Mariner Venus), a lonely cyborg staffer of a trading post literally holds you captive while she tells the sad story of how she lost her love.

By turns horrifying and heartbreaking, it's a moving piece. Four stars.

The Peacock King, by Larry McCombs and Ted White

Less effective though more experimental is this piece on the first successful hyperdrive jaunt. After four failures, it is determined that the transition to hyperspace bears similarities to drug-induced schizophrenia. One couple, so in love as to practically share a consciousness, is fed a regimen of psychoactives to prepare them for the trip.

Somewhat roughly written, and perhaps too short, it is nevertheless a fascinatingly "now" story delving into new territory.

Three stars.

Insect Attractant, by Theodore L. Thomas

This usually disappointing column of sf-story ideas masquerading as short science articles starts promisingly, discussing how insect pests could be eradicated through synthesis of female sex pheromones, which could then be sprayed to disrupt their breeding cycles. A fine alternative to DDT.

But then he goes on to suggest that human females have similar pheromones, and that distillation and application of same could be used by marriage counselors, as if love is purely a matter of chemical compatibility. Perhaps the author has never been in love, let alone gotten married. Of course, Mr. Thomas may have meant the piece in jest, though I also resented its casually sexist overtones. Either way, it's not worth the page it occupies.

Two stars — and let's please 86 this column, Mr. Ferman?

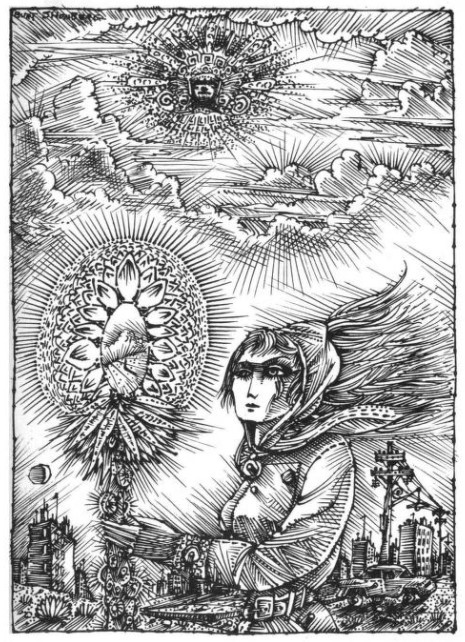

… And Call Me Conrad (Part 2 of 2), by Roger Zelazny

When last we left Konstantin Karaghiosis, Minister for Cultural Sites on an atomics-devastated Earth, he was giving a tour of Greece to a blue-skinned Vegan, name of Cort Vishtigo, and his human entourage. Ostensibly, the alien was on Earth to write a travelogue. His true purpose is unknown, but the members of the Radpol movement believe Vishtigo's trip is a real estate survey, prelude to the Vegans buying up the planet to plunder. An assassination attempt is in the offing, and Karaghiosis (virtually immortal and currently going by the name of Conrad) believes that the alien's bodyguard, Hassan, is the likely killer.

That's the context, but the tale Zelazny weaves reads like a modern interpretation of mythology, with Conrad's party encountering a host of radiation mutated beasts, humans, and everything in-between. Conrad is a tale of survival, of derring do, of proving worth. It's also a pretty good mystery with a satisfying, if a touch too pat, ending.

At first, I was leery of Zelazny's style, a first person macho that threatens to become precious. But there's enough self-deprecatory humor to make it work, and I found the pages flying. There's enough action to keep it moving, enough depth to keep you thinking.

Four stars for this segment, and the novel as a whole is elevated to this rank as well.

El Numero Uno, by Sasha Gilien

It used to be that Death attended to matters personally. Now, the business has boomed, and he requires field agents armed with legal contracts instead of scythes. This particular case involves a harried operative on the sports beat and a particularly recalcitrant matador scheduled for expiration.

Good stuff in the style of Ron Goulart. Four stars.

Squ-u-u-ush!, by Isaac Asimov

Having previously discussed the shortest measure of time, the largest measures of dimension, the hottest heat, and the coldest cold, the Good Doctor now explores the densest densities, starting with ordinary matter and proceeding the greatest crushes in the universe: the interior of giant stars.

Cutting edge stuff, and it's the first time I learned of neutronium, a state of matter even more compressed than that found inside a white dwarf.

Four stars.

A Few Kindred Spirits, by John Christopher

Last up, the much heralded author of No Blade of Grass offers up a tale combining a queer (in both senses of the word) group of dogs, the concept of reincarnation, and the pursuit of literary laurels. A character study cum literal shaggy dog story, it's perhaps the most conventional piece of the issue — save for the rather daring (and refreshingly uncondemned) discussion of alternate sexual preferences.

Four stars.

The Sound of Shoes Dropping

It is clear that, after a long many-tacked jaunt in trackless seas, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction has set a bold new course. I have high hopes and more than a little suspicion that this New Wave era has many more exciting years left to it.

After quite a few lean years, I'm finally getting my dessert again!

![[October 18, 1965] Turn, Turn, Turn (November 1965 <i>Fantasy & Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651018cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 10, 1965] Doctor Where? (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Mission To The Unknown)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651010recording-672x372.jpg)

![[October 8, 1965] Handle with Care (<i>Forbidden Planet</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651010a-672x372.jpg)

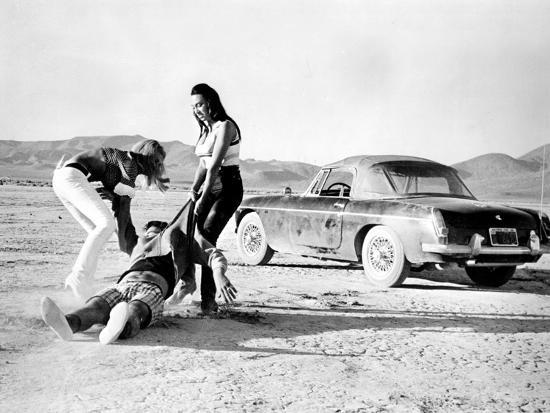

![[October 6, 1965] Go, baby, go! (<i>Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/99f21f4b8fd97f8ef16ec5f38a6030ae-2-500x372.png)

![[October 4, 1965] Galaxy Bore (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Galaxy 4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651004chumbleyonpatrol-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1965] Gimmickry (November 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/1965-11-IF-cover-645x372.jpg)

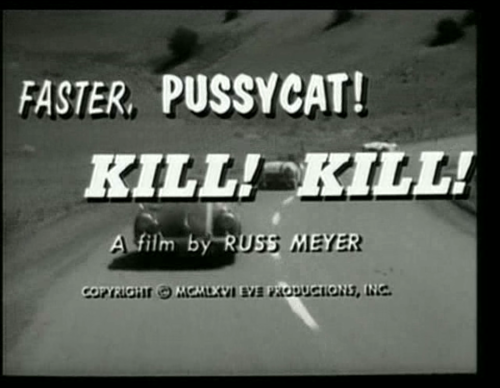

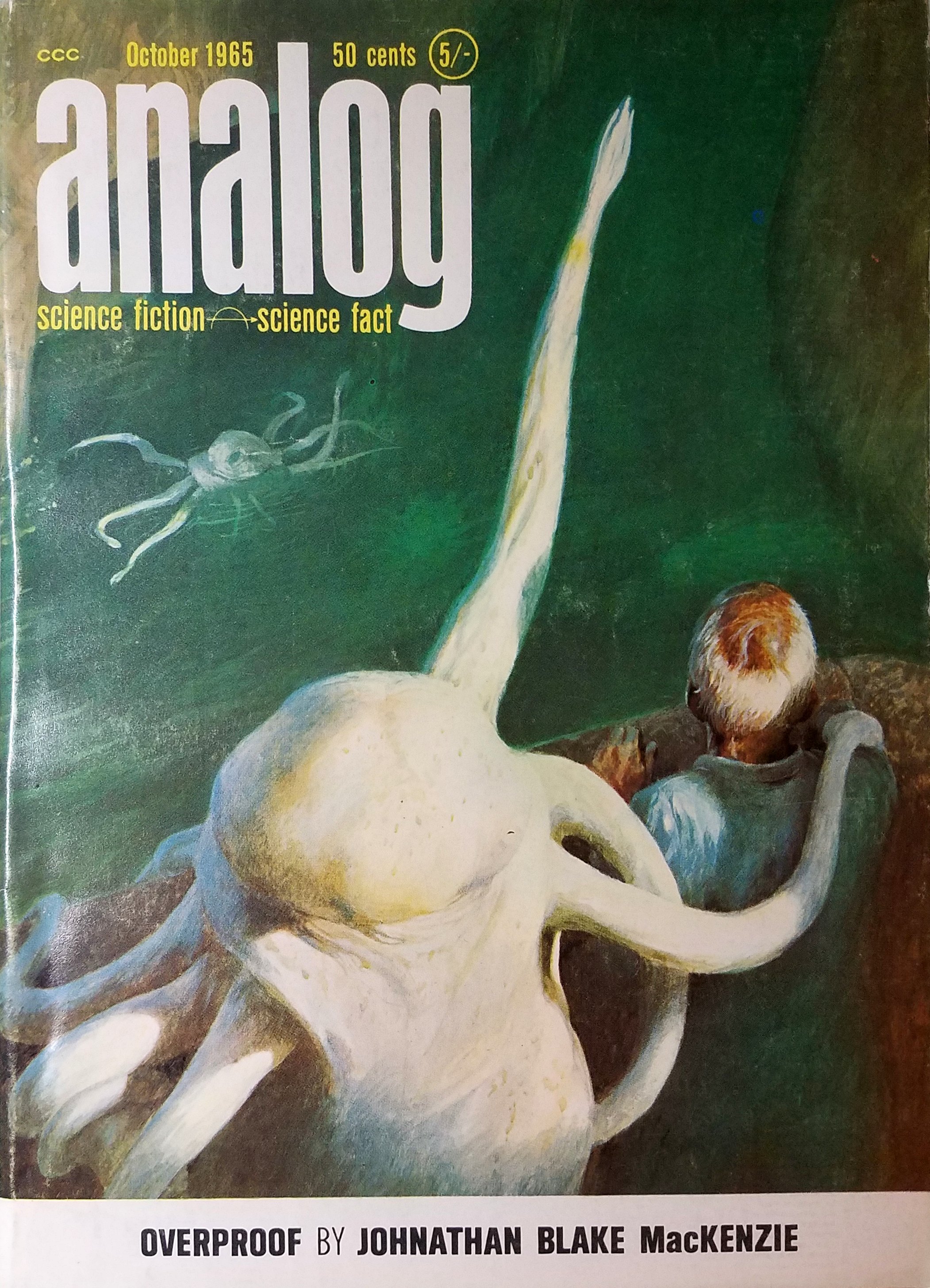

![[September 30, 1965] Big and Little Bangs (October 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650930cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 26, 1965] Allegory and Mythology <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, October 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/sf-nw-october-1965-672x372.png)

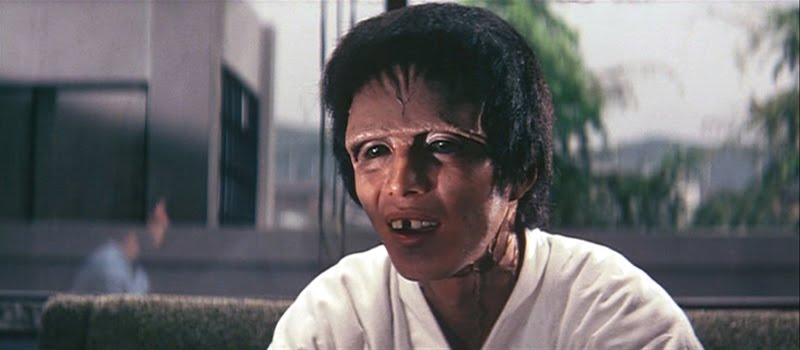

![[September 24, 1965] False Advertising (<i>Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster</i> and a brief history of Mary Shelley's creation on film)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/4d6e7604f0053e87ac44cfd4c8fb9dd0e9de58b6r1-749-920v2_hq-2-672x361.jpg)

![[September 22, 1965] Foul! (September Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650922covers-656x372.jpg)