Better Than Perry Mason

by Jessica Dickinson Goodman

In Court Martial, we see Star Trek trying on a new genre: courtroom drama. Like a good Perry Mason episode, we have twists, turns, dramatic monologues on the subject of rights, stodgy courtroom pedantry, and a wicked villain who gets his comeuppance before the hour is up.

But it being Star Trek, it added some important layers to the genre. Our Perry Mason – a stolid Luddite named Samuel T. Cogley (Elisha Cook Jr.) – is less dapper and more dogged in his defense of Captain Kirk. Unlike any Perry Mason I can remember, the prosecutor is a woman (Joan Marshall as Areel Shaw), and the four judge panel is played by actors who can trace their family trees to nearly every continent on Earth, including Commodore Stone (played by the excellent Percy Rodriguez), Starship Captain Chandra (Reginald Lal Singh), Starship Captain Krasnovsky (Bart Conrad), and Space Command Representative Lindstrom (William Meader).

A nice cross-section of ethnicity, if not gender

Percy Rodriguez was born in Montreal and is of Afro-Portuguese descent (that gets us three continents right there). Reginald Lal Singh was born to Indian parents in what was then the mainland of the British West Indies and is, as of May 26, 1966 the independent state of Guyana (which gets us two more continents, plus a second count in Europe’s column for the British passport). Then add in the unnamed Ensign who appeared to be of East Asian descent, and we don’t even need to count real-life U.S. Army Colonel Bart Conrad, who as it happens, also worked in several episodes of Perry Mason.

I don’t list these actor’s family histories to distract from their professional credits, but to note that Star Trek manages to reflect our world in ways that many theoretically more realistic shows do not. Afterall, we are a country which first elected Dalip Singh Saund to the U.S. Congress in 1955, and seven years later, appointed Thurgood Marshall to the Second Circuit Federal Court of Appeals, the brave lawyer who argued Brown v. Board of Education before the still all white, all male U.S. Supreme Court. (Perhaps 1967 will be the year at least one of those descriptors changes).

The Supreme Court, in 1962

Today, there are dozens of Black judges serving on the federal, state, and municipal bench – including Vince Townsend, a municipal judge in Los Angeles County who played a judge in the 1963 Perry Mason episode “The Case of the Skeleton's Closet” (and, because the world is tiny, I have heard that Judge Vince Townsend used to be roommates with Judge Thurgood Marshall). So why do we need to look hundreds of years into the future to see judges and captains and prosecutors who reflect our real world?

Perry Mason, in the courtroom

As interesting as the casting was for this episode, the plot itself also held my attention. First, we think we’re about to follow a routine investigation into the tragic death of a crewman. Then his daughter appears, wild with grief and accusatory in speech. Things begin to shift for Captain Kirk, his colleagues turning their shoulders at him, an old flame warning him of impending disgrace, and a trial which forces his nearest and dearest officers to testify fairly damningly against him.

But then in hops our very own Perry Mason, with clever words about rights and the flaws of technology. Cogley convinces the judges to return to the Enterprise where my very favorite moment of the episode happens: a luscious soundscape of heartbeats that is slowly narrowed down to a single, unknown body, stowed away belowdecks.

Well, second favorite; as I am sure Erica will concur, watching Captain Kirk roll around on the floor and tear his shirt on the carpet isn’t a bad use of screen time either (another common Star Trek cliché that Perry Mason never included).

Two absolutely convincing stunt doubles fighting in Engineering

The episode lost most of its tension at this point, as we waited for an increasingly barechested Captain Kirk to corral the previously-thought-dead Lieutenant Commander Finney and stop him from crashing the Enterprise into the planet’s surface.

The little twist at the end, where we discover Cogley has now agreed to represent Lieutenant Commander Finney, was a nice touch.

This episode gave meaty, well-developed roles to Areel Shaw and Percy Rodriguez, giving them space to explore courtroom theatrics and protocols in roles many drama’s casting directors would have given only to white men. Though parts of this episode flagged, that delightful choice carried it through for me.

Rating: 4 Stars.

Wrong Way Street

by Abigail Beaman

While I know a majority of my peers rated this episode highly, I was let down by the ending of the episode. I feel that Trek has worked best when it left me with some warning or moral, and to have it just devolve to fisticuffs and Kirk half naked at the end just seemed to disappoint. And believe me, I like when the cast gets half naked.

Perhaps I was just expecting a different story. "Court Martial" opens up with what we believe will be a man versus machine parable, with Kirk versus the computer of the Enterprise. Instead we end up with man versus man: Kirk versus Finney. I feel like if Marc Daniels had followed through with the theme "don’t trust machines on everything", I would have happily rated this episode above a four.

Computers–who needs 'em?

My biggest issue is with Finney being alive. It raises many unanswered questions. What was Finney’s plan after Kirk got indicted? How did Finney manage to change the computer without being spotted? How did Finney even get out of the pod before it was sent off? How did messing with the data stored in the computer also mess up Spock’s chess programming?

In the end, I was just disappointed and annoyed. While the story started off strong, it ended up crashing in the climax, leaving a sour taste in my mouth. That’s why I rate it 2.5 stars.

Our Perception: what can and can’t we trust?

by Andrea Castaneda

I agree with my colleague, Abby, though perhaps the premise saves this episode a little more for me. “Court Martial” was, to me, one of the more intriguing episodes in the show of the series. We’re presented with high emotional stakes, see a more vulnerable side to Captain Kirk, and take a deeper look into how StarFleet operates. But what I liked most about this episode was how it analyzes man’s perception in contrast to the cold hard evidence of the machine.

The courtroom scene reminded me a lot of Sidney Lumet’s “Twelve Angry Men”. In that film, eleven men of a jury believe a man guilty of murder, but one juror still wants to discuss how there can be doubt. The film goes on to dissect how one’s perception can be warped by emotion, physical limitations, personal beliefs, etc. In the end, they conclude the provided evidence is insufficient, and the defendant is spared from the electric chair.

Twelve Angry Men, perhaps the seminal courtroom drama of the last decade.

This episode shared similar themes. Kirk starts out unwavering in his confidence. But when presented with seemingly damning evidence, he’s shaken. With a defeated tone, he says to himself “but that’s not the way it happened.”

But unlike “Twelve Angry Men”, Spock subverts the idea that man’s memory is inherently flawed. When the prosecution asks him how he could know Kirk did the right thing if he didn’t see him, he states that one doesn’t need to observe him at all times to know he did. Just as one doesn’t need to see a dropped hammer fall to know it has in fact fallen. And while he does concede that this is– at the end of the day– his opinion, his confidence in Kirk is what prompts him to prove the computer is wrong. And of course, he tests the system via chess.

Where the episode missed an opportunity, however, was how they chose to end it. I was hoping that once Spock proved the computer was faulty, it would lead the court to reevaluate the evidence and/or rule that the man’s death was due to a programming glitch. But instead, it’s revealed that the dead man was alive the whole time, and that this was all part of a half-baked revenge plot. He and Kirk wrestle while the Enterprise is set to crash, but Kirk once again saves the day. And with that, what started out as a sober courtroom drama winds up as a James Bond movie.

Ridiculous as that ending was, I still thoroughly enjoyed the mental analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of one’s perception. It gives me as a viewer something to think about once the episode ends. Unfortunately, the conclusion of events– including Kirk’s unprofessional kiss with the prosecution lawyer– compels me to declare “Court Martial” a mistrial.

Three stars.

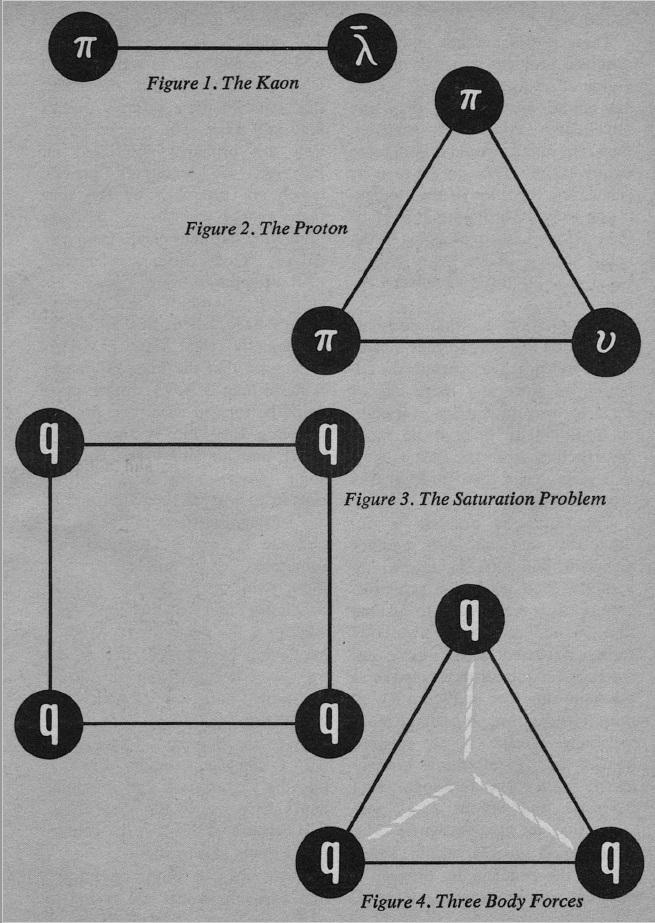

Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

by Lorelei Marcus

"Court Martial" is the second trial-centered episode we've seen on Star Trek, though unlike "The Menagerie" (and many other episodes) there are no God-like aliens or other fantastical features. Which is why "Court Martial" is one of my favorite episodes: because of its focus on technology and its ability to straddle the line between implausibility and familiarity.

The source of conflict in this episode is the malfunction of the ship's "computer". The show portrays this computer as a piece of machinery so complex it can recognize verbal commands, act as an archive of all human knowledge, and even play chess! Yet it's so small that it can fit into a panel console [I think those are just the teletype terminals. Cogley's law computer seems self-contained, though. (Ed.)] This is far more advanced than anything we have today, or anything that could conceivably be developed in the next 50 years.

"Computers. I know all about them."

However, the audience is not totally disconnected from this incomprehensible device because the computer represents more than itself. When Kirk first meets his defense lawyer, he is startled by the lawyer's reliance on paper books over computer banks. In the Star Trek future, physical books are an antiquated and nearly extinct form of information storage. While this is a rather extreme (and grim) prediction, the situation does reflect a trend toward a reliance on technology over physical media happening in our society today.

Rather than read the paper or a novel, we increasingly watch the news or a Western on television. We've long since switched computation work at NASA from "computers" (actual human beings doing calculations) to IBM's metal monsters. It isn't a stretch to see a future where the development of computers alters the very way society operates and exists, eschewing personal bonds of trust and the evidence of the human eye. Someday, we may even leave justice to the computers themselves – after all, they cannot lie, can they?

Except, of course, they can. Because people can, and computers are still, even in the far future, servants of people. That, I think, was the point of the episode, and a good one.

Four stars.

The measure of a man

by Tam Phan (Secret Asian Man)

It doesn’t always feel good to do the right thing, but there’s something to be said about having complete confidence in your integrity when it’s under scrutiny. Kirk walks confidently into most situations as if he always has the right answers. Ben Finney is not Jim Kirk. Without even getting to know him that well, it’s still abundantly clear that the infraction that he received wasn’t the real reason he wasn’t a senior officer.

As the records officer, Finney seemed to be doing just fine. After all, he was an officer aboard the Starship Enterprise. It’s not clear if there are many other starships, but as far as we know, the Enterprise is a very important one. [Last episode, it was revealed "there are only twelve like it in the fleet" (ed.)] If Spock’s and McCoy’s commendations aren't enough to tell us how much prestige is represented in the ship's crew, Kirk’s commendations practically flaunt it. I assume that Finney’s service record must be relatively strong to serve on such a ship, but his actions in “Court Martial” tell us everything we need to know about why he’s not captain of his own starship.

Captain material?

Finney’s ability to sabotage the ship shows us that he’s clearly competent, but his plan lacked any forethought; a trait that is expected in leadership. What did he think was going to happen once Kirk was court martialed? Life couldn’t go back to normal for Benjamin Finney. He was on record as being jettisoned and presumed to be dead. It’s not as if he could return to being Enterprise’s records officer. At the very least, he’d have to escape the Enterprise and go into Richard Kimble-style exile. He didn't even manage to do that!

In short, he didn’t have the fortitude to move on from a decade-old perceived personal slight, instead developing a grudge. He didn’t have the integrity to own his mistakes, and so he blamed Kirk. He failed to weigh the possible consequences of his actions, either in the past or of his current half-baked scheme. But I don't condemn Finney for this. For all of his flaws, Finney is a perfectly understandable character, a human character. I get him, even if I don't grok him, and his relationship with Kirk was poignant and interesting.

In the end, no one is perfect: not the records officer nor the computer he works on.

4 Stars

The Little Black Box

by Janice L. Newman

As a fan of mysteries, I really enjoyed Court Martial. The episode did a good job of building tension throughout, even making the audience second-guess ourselves. One thing that I thought was an interesting touch was the recordings made of the events on the bridge and played back later for the purposes of the trial. We saw something similar in "The Menagerie", but in that case the playback was facilitated by the aliens. In Court Martial the implication is that the recordings are done automatically, presumably for circumstances like those in the episode.

This year (1967) regulations are going into effect that state that all planes must have a ‘black box’ installed—that is, a flight recorder that can help explain the cause of a crash after the fact. Having cameras on the bridge that record everything is a natural extrapolation of this new technology and makes perfect sense. And when the audience ‘sees’ Captain Kirk push the wrong button at the wrong time, even many of us are fooled for a moment, wondering, ‘Maybe he just made a mistake?’

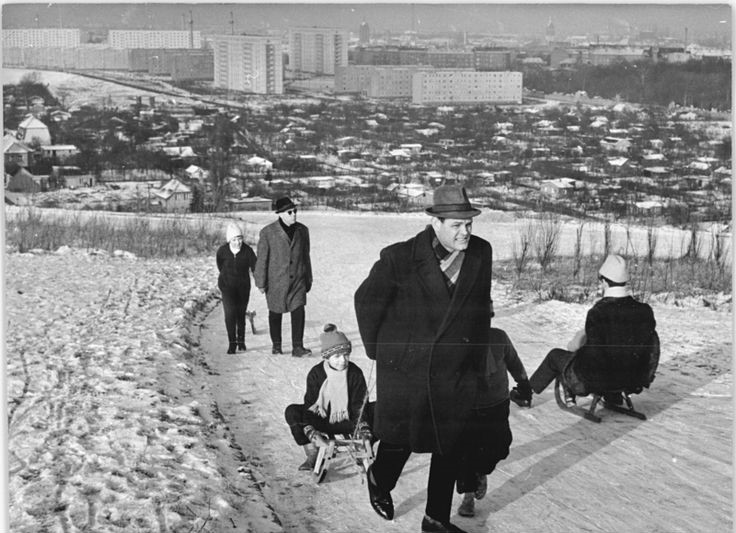

A Soviet flight recorder – a "red box"?

It’s not a perfect episode. The denouement, where Captain Kirk is permitted to face the man who has a personal vendetta against him and engage in fisticuffs, didn’t make much sense. Nor did Finney’s plan: did he plan to hide out for the rest of his life? Was he going to get Harry Mudd to make him a false identity? What about his daughter?

Despite these caveats, I liked the mystery and the story overall, and particularly found the dramatic scene where each person’s heartbeat was screened out to be nail-bitingly effective. It was also refreshing not to be dealing with godlike aliens. I give this episode four stars.

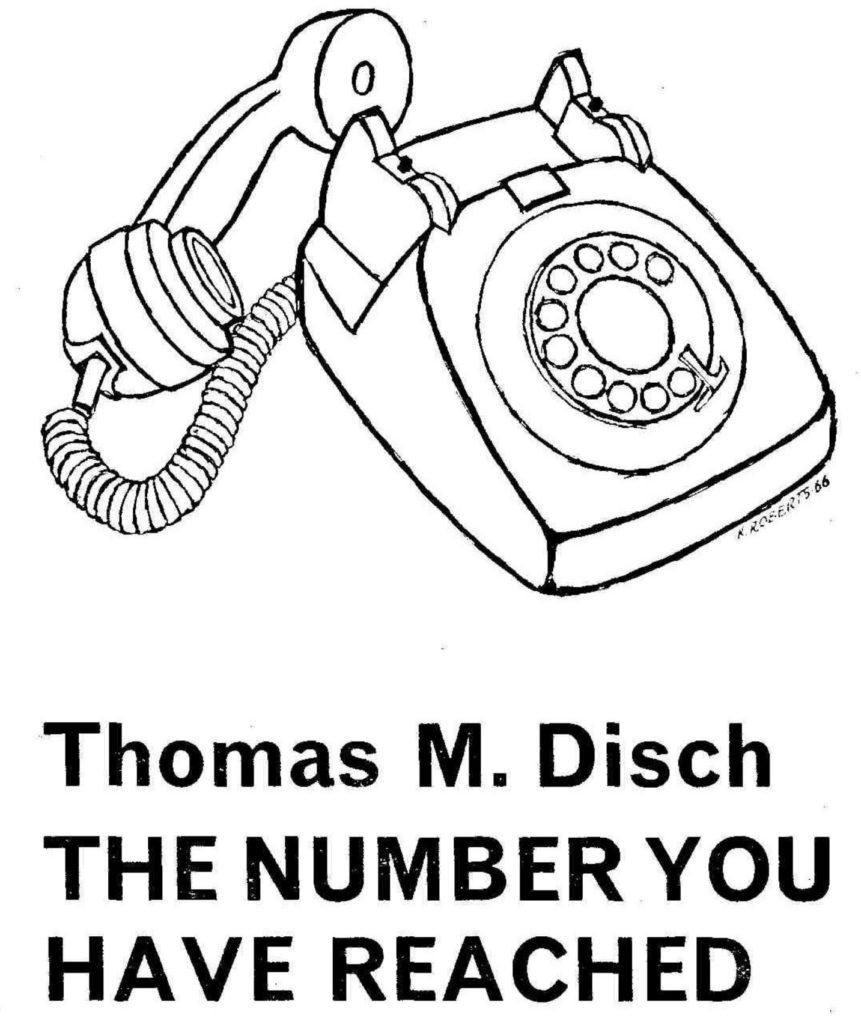

The Return of Shirtless Kirk

by Erica Frank

Other viewers have covered the plot, the characters, and the nuances of the legal system. I'm going to focus on something more fun: The clothing, and occasional lack thereof.

We never meet the people who design Starfleet's uniforms, but they must be very influential. There's so much variety! You'd think people living on a spaceship would have limited resources, but no: everyone has uniforms in several colors and styles.

A trial is a formal event, which calls for formal apparel. Naturally, Starfleet's fashion designers rise to the occasion. First, we get Kirk in his side-wrap shirt, while he meets with Commodore Stone to discuss the accusations against him. This seems to be more formal than the normal pullover uniform.

Kirk's wraparound green uniform

The Commodore's outfit is similar to the Enterprise crew's standard ones, but his insignia is a sparkling flower brooch. Very nice.

Kirk changes back to his gold pullover to meet with an old friend; she's in a wild pink-and-green paisley gown. Later, in the courtroom, she wears a red minidress, very similar to Uhura's outfit, only with another flower brooch. I might have mistaken it for mere jewelry if I hadn't seen the same on the Commodore earlier.

This is what lawyers in Starfleet wear when they're not in court.

Dress uniforms—which is what I assume the officers are wearing in court—are satin, with gold trim, and the insignia is an array of triangular gemstones. They seem to open down the front; I approve of Starfleet's apparent policy that the more formal the outfit, the easier it should be to remove. (I'm glad someone in Starfleet is focused on practical issues.) As one would expect, the Commodore has more sparkles than a mere captain, even considering Kirk's impressive record.

Which of Kirk's triangles is the Grankite Order of Tactics? Is the thing on the side the Prantares Ribbon of Commendation? (Do enlisted personnel just have one or two little triangles?)

He can fight a Gorn on a planet full of gemstone rocks and not lose a thread, but when he's up against anyone he knew at the Academy, he loses clothing. He must have been terrible at strip poker.

This episode raised some questions, like: Why must Spock win at chess to prove that computer records can be altered? But I am willing to look past quite a few loopholes to see Kirk half-undressed and on his knees.

I'm not quite as shallow as that sounds. I'm just aware that we viewers often put more thought into the worlds and societies than TV writers have time to develop. I watch this show to have fun; I enjoy the science fiction elements as best I can, but when they're a bit weak, I am happy to be distracted by petty pleasures.

Three and a half stars. I know too much about the law to give it four.

Week before last, it was I Dream of Jeannie. Now, it looks like the Enterprise crew will be on Wild, Wild West! Come join us tomorrow at 8:30 PM (Eastern and Pacific).

Here's the invitation!

![[February 8, 1967] Hung Jury (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Court Martial")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670208title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 6, 1967] Nothing In The World Can Stop Me Now! (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Underwater Menace)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670206atlanteans-672x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1967] The Sweet (?) New Style (March 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IF-Cover-1967-02-full-672x372.jpg)

![[February 2, 1967] It's About Time (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Tomorrow is Yesterday")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670202title-672x372.jpg)

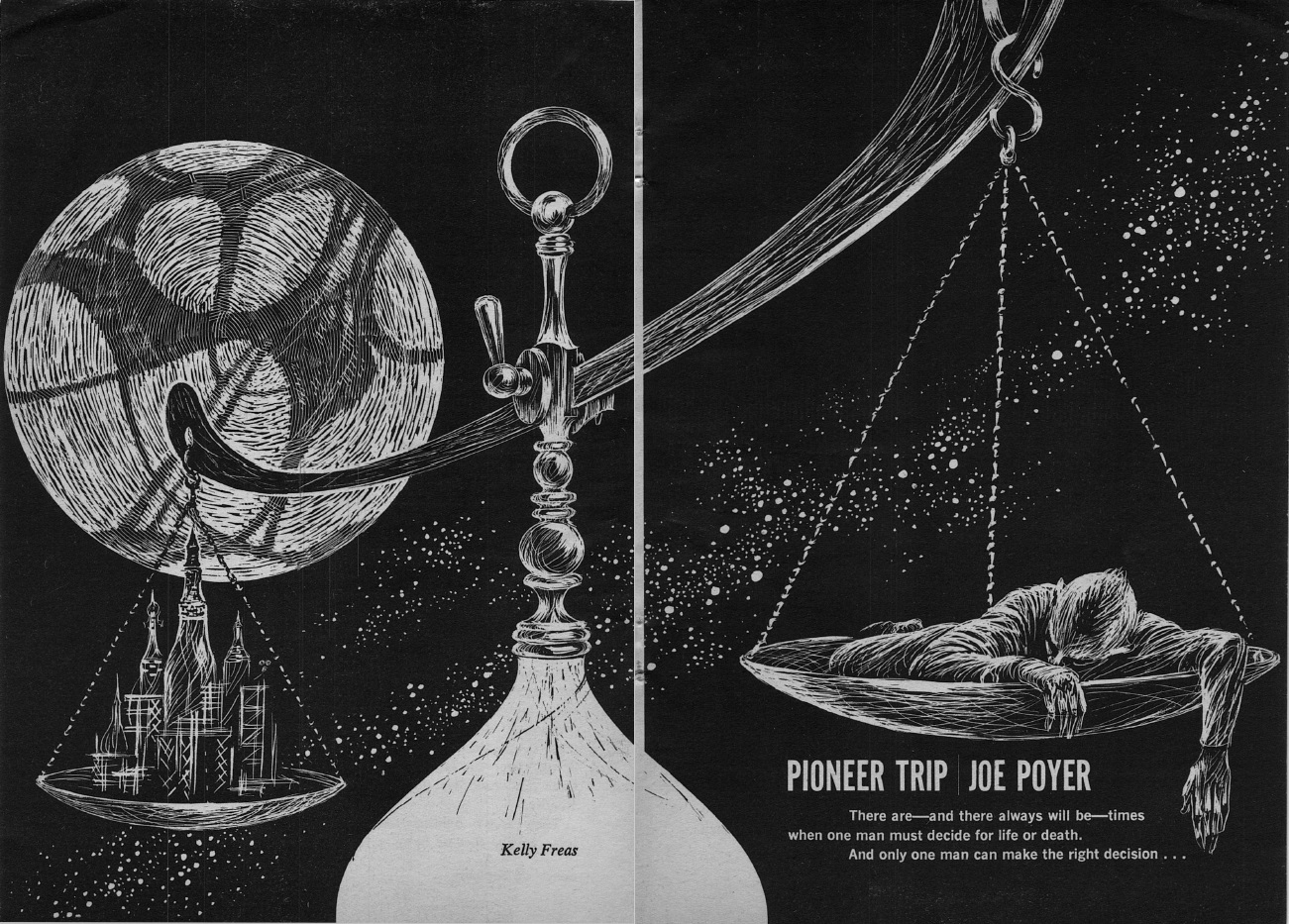

![[January 31, 1967] The Law of Averages (February 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670131cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 26, 1967] Cold-blooded murder (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Arena")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670126title-672x372.jpg)

![[January 24, 1967] Absenteeism and Making Do <i>SF Impulse</i>, February 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/SF-Impulse-Jan-67-672x372.jpg)

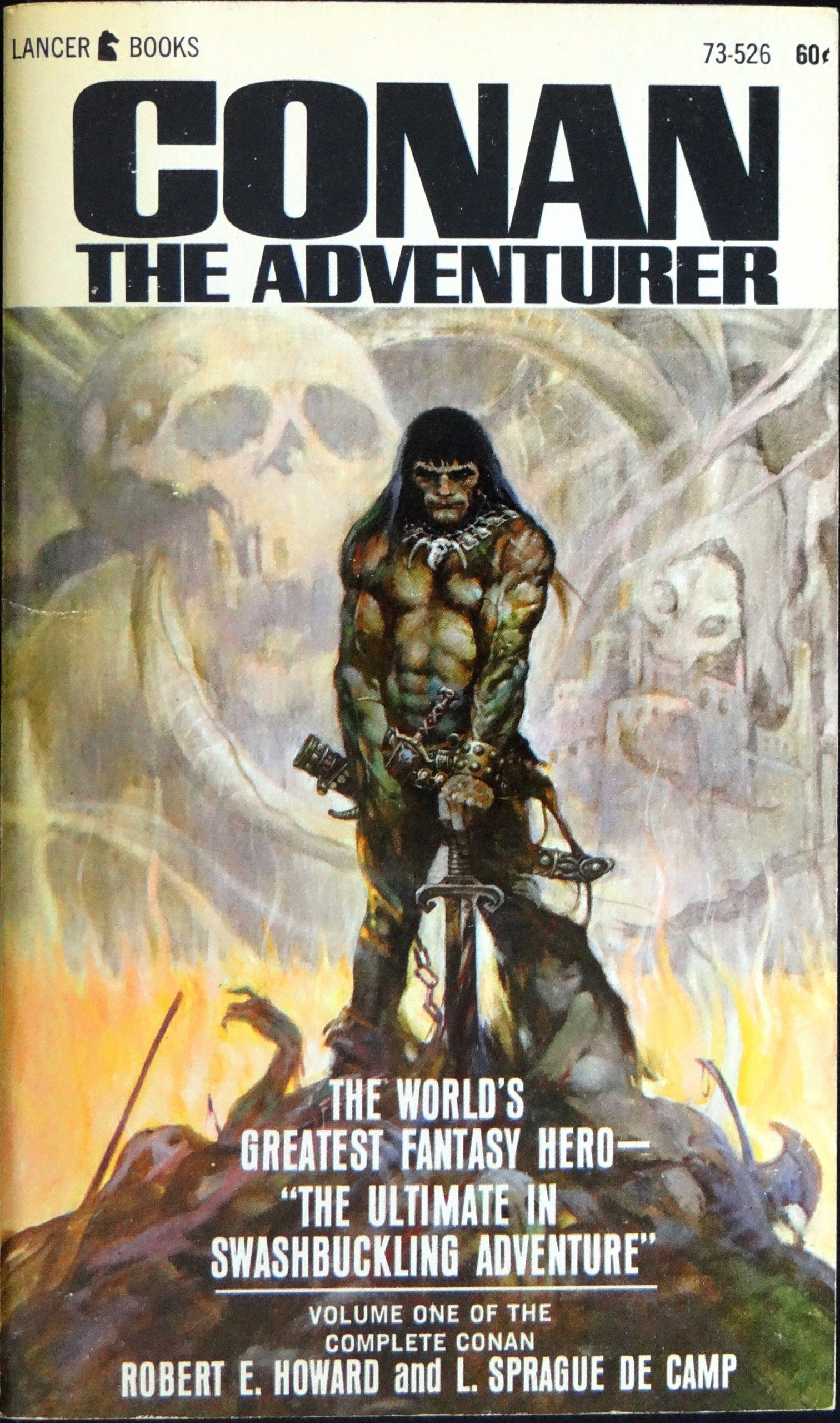

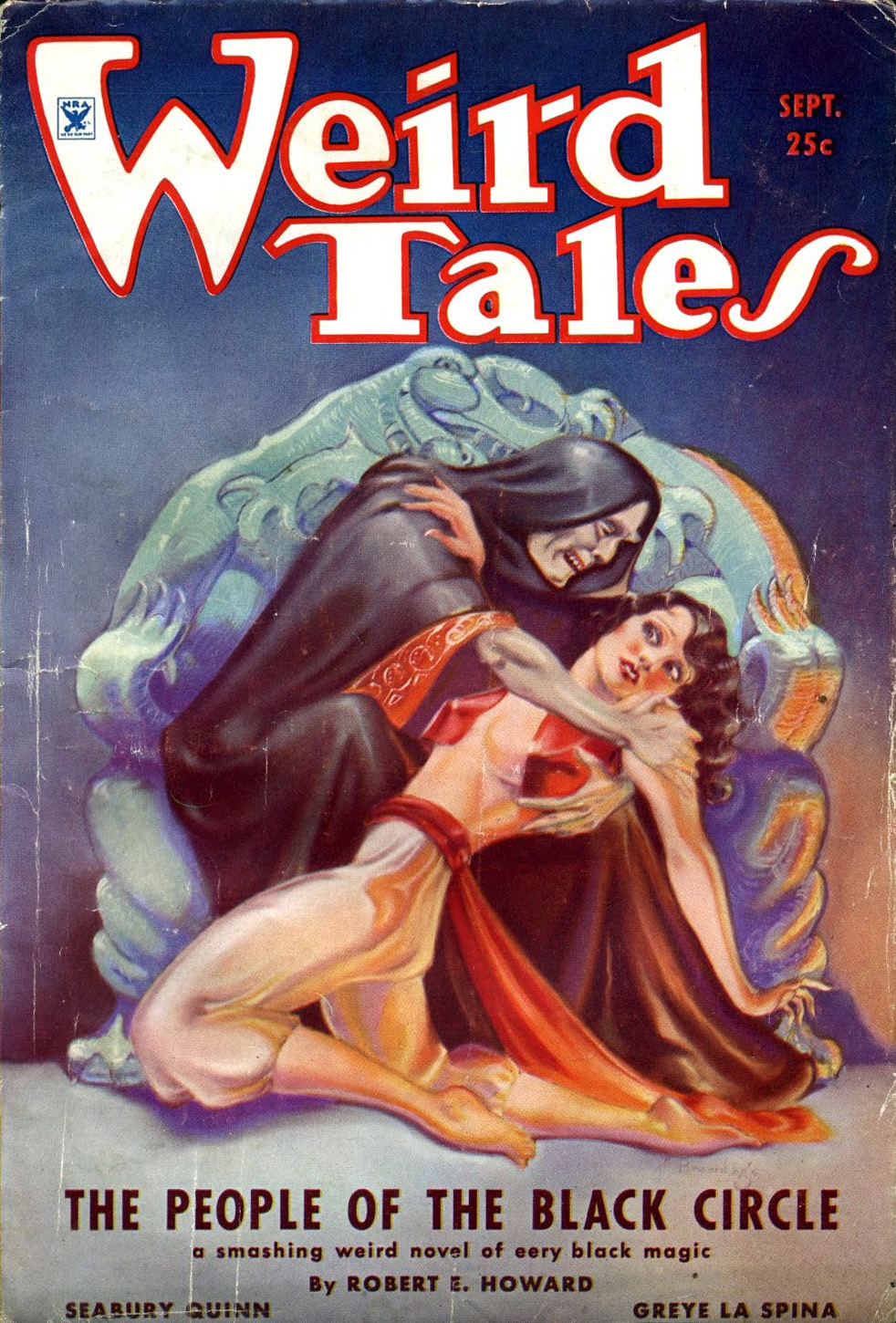

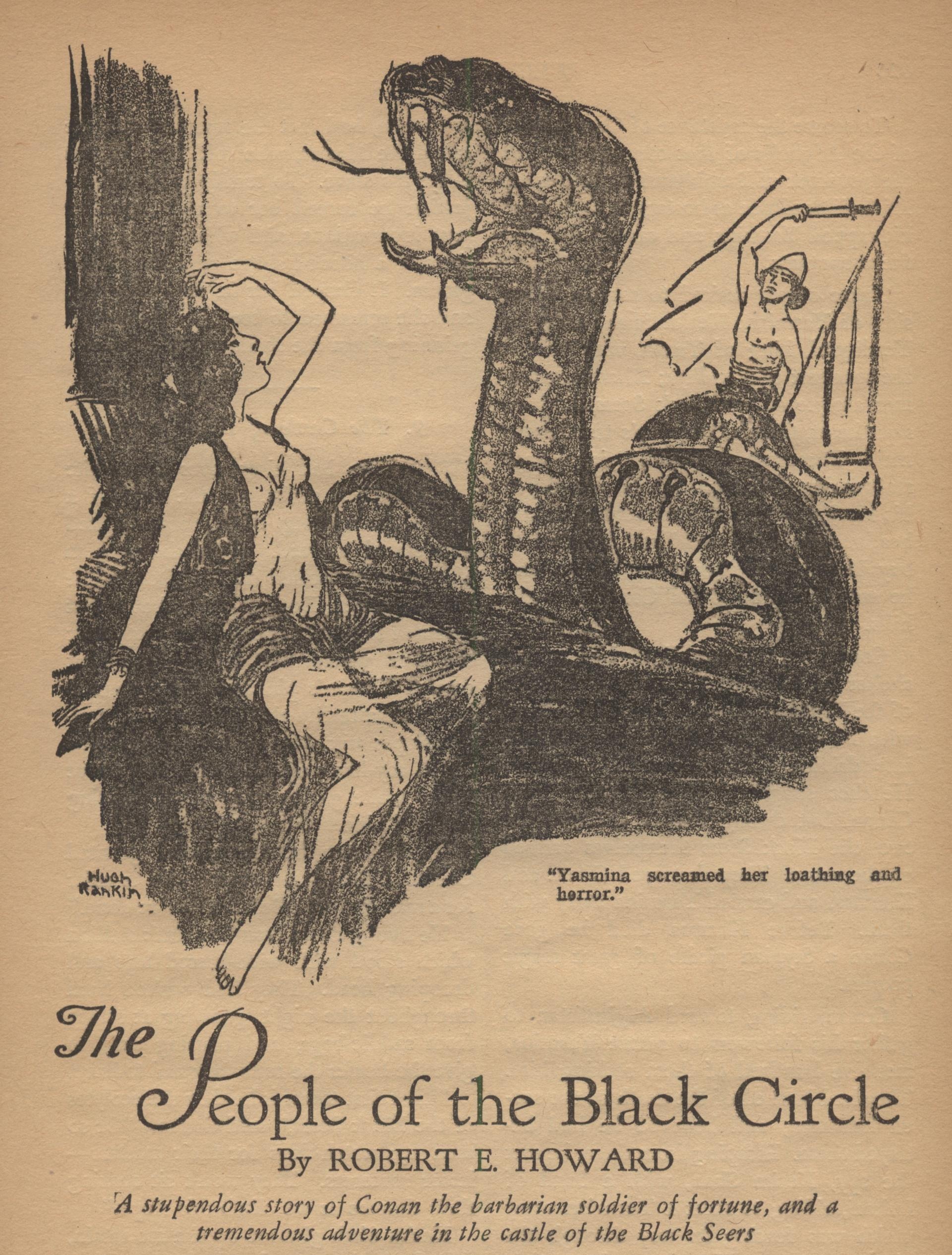

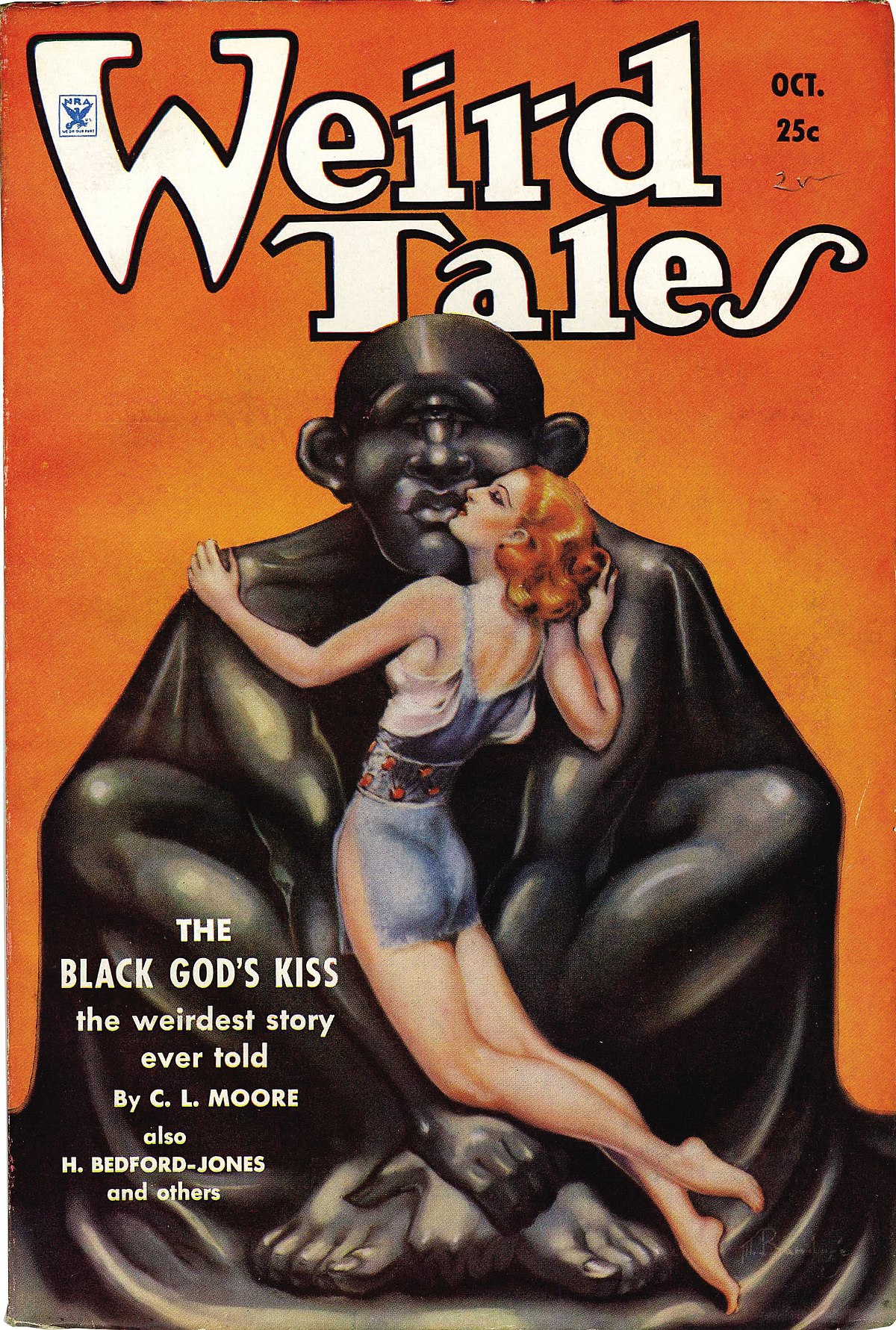

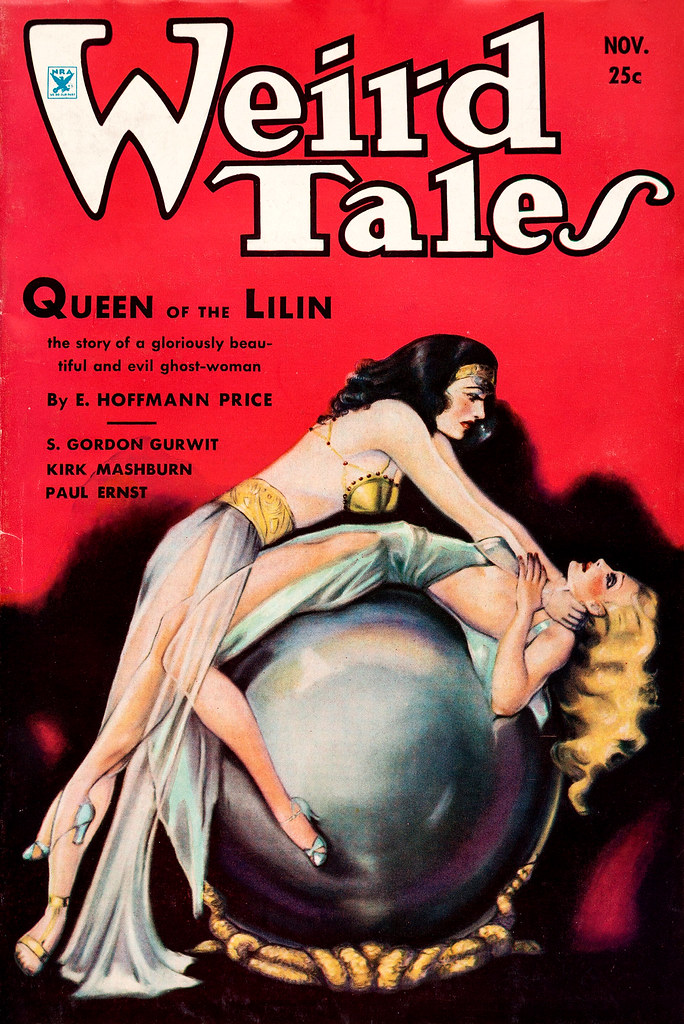

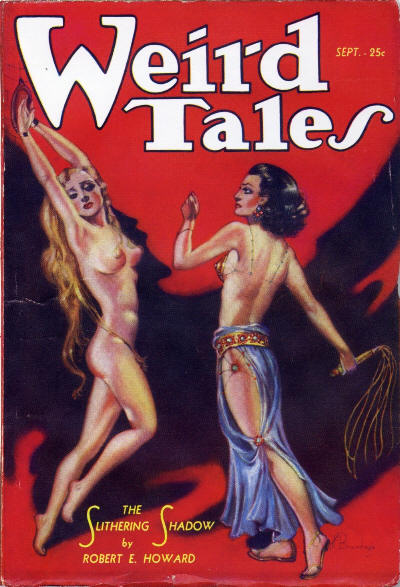

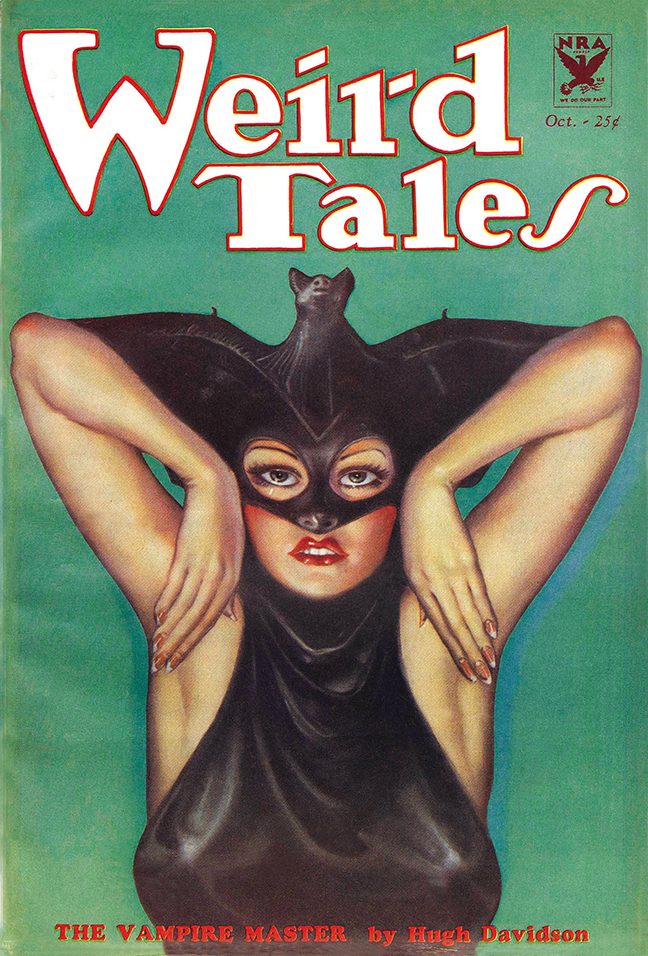

![[January 22, 1967] The Return of the Cimmerian: <i>Conan the Adventurer</i> by Robert E. Howard](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/14539434635_ea7488eae9_o-672x372.jpg)

![[January 20, 1967] Sag in the middle (February <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670120cover-1-422x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1967] Temper tantrum (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Squire of Gothos")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670118title-672x372.jpg)