by Gideon Marcus

Last minute reprieve

If you're just an average, everyday stf-loving citizen, you've probably been feeling pretty secure about the new show, Star Trek. After all, it's leaps and bounds better than any other SFnal show on TV (e.g. Voyage to the Bottom of the Aquarium, It's About Time (this show got canceled), Time Sink, Lost in Spoof, The Invasive, etc.) Surely if Irwin Allen can get his shows renewed, Gene Roddenberry can, right?

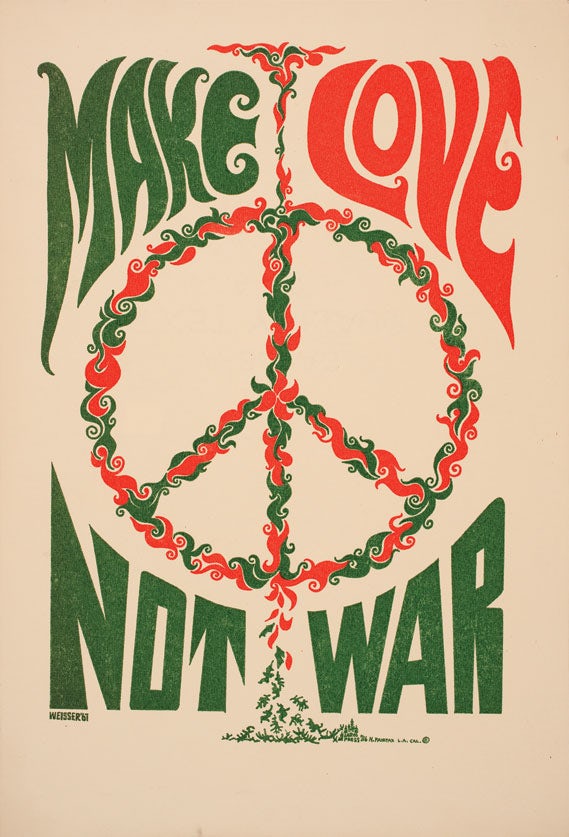

Well, maybe not. Late last year, the fanzines and club meetings were abuzz. Seems Harlan Ellison had sent out a written plea, letterheaded by more than half a dozen Big Names in the SF screenwriting biz (self-importantly dubbed 'The Committee') begging trufans to write their local stations, NBC, Desilu, the Pope, etc. voicing their support of the show. Otherwise, it might not finish out the season and certainly won't get renewed.

This call was met mostly with enthusiasm, though there were cynics. Thousands of letters were sent (one over-enthusiastic fan conjectured the number was "around a million"). It now appears that Trek will run another season after this one is done.

There is something of a preemptive quality about all of this. Talking to astute newspaper-clippers and folks in the know, I learned that Trek was greenlit for a full season back in October, before the alarm was sounded. Now, I don't think it's a bad idea to tell the powers-that-be how much you like a show to make sure it stays on longer than the usual crud, but I worry that this may have been a bit of crying wolf. If the network really does plan to axe this lovely new SF show in the future, will they take us seriously then? Tune in next winter, I guess.

An Orgy of Destruction

Speaking of last-minute reprieves, this week's Trek episode, "Return of the Archons", was full of 'em.

Investigating the loss of the starship Archon decades before, the Enterprise visits Beta 3, an uncharted world. The episode begins quite effectively with a cold open: Lieutenants Sulu and O'Neill, in Western garb, are being chased through a nameless 19th Century-style city, completely unadorned with signs or other decoration. Before Sulu can be beamed aboard to safety, he is zapped by goons in monk robes. Once aboard the ship, the vivacious helmsman is reduced to a grinning imbecile, now one with "the body".

In perhaps the greatest disregard for sense I've yet seen on the show, three of the most senior crew transport down to investigate. There, they find a world of zombie people, placid, without will. Except that night is "Festival", an uncommon but periodic occurrence when the muzzle is removed and people give in to their urge to lust and rapine. All of this, the mindlessness and the maelstrom, is the will of "Landru", some sort of omnipotent, telepathic God.

Landru.

Some of the Betans are resistant to being "absorbed" into the body, however. They do their best to help Kirk and co., though they fail to prevent Dr. McCoy (who the captain jarringly keeps calling "Doc" rather than "Bones" in this episode) from losing his mind to Landru. It is determined that this status quo has existed for 6,000 years, a reaction to a period of world-threatening savagery. Landru was a real fellow who set up this completely (except for Festival) peaceful and static society to save the people of Beta 3.

It worked, but only at the cost of the human soul. And, as Kirk and Spock correctly guess, only a soulless entity could create such an order: in this case, a computer of Landru's construction. When directly confronted, the computer quickly gives up the ghost, and Beta 3 is left rudderless. A team of sociologists (the Enterprise conveniently has them on hand) stays behind to provide better guidance than LANDRUVAC.

My colleagues will discuss the various elements of this episode in subsequent sections so I'll keep my comments narrow. "Return" is quite a good episode, utilizing existing costumes and sets (for other Desilu shows, presumably) to get more bang for the budget (though if the Enterprise had a panoply of outfits they got from Bonanza, you'd think they'd have them for other eras, too – would have been useful when they visited modern day in Tomorrow is Yesterday! There are inconsistencies and some areas underdeveloped due to lack of time, but the show flows pretty well.

If only they'd had access to this wardrobe in earlier episodes…

There are lots of messages one can divine from "Return", notably the "computer-driven society is bad" message we've gotten a few times before. Going deeper, particularly tying in with Spock's noting that the peace and tranquility of Beta 3 is that of the factory, the machine, I discern an indictment of Communism. "From each according to their ability, to each according to their need" sounds like a good idea in theory, but it robs humans of their individual dignity, placing power solely at the venal top. Landru's projected image, with his robes and cult of personality, calls to mind Mao and Confucius, with inflexible dogma and inescapable "justice".

Such a society clearly cannot stand. I wonder, however, if simply toppling the big boss and (mostly) leaving the wrecked culture to fend for itself, is the best way to ensure a future of democratic enlightenment.

Four stars. It's solid entertainment for all its stumbles.

Silicon life?

by Abigail Beaman

If something does not feel, only does what it is told, and shows no creativity, is it alive? That’s what this week's episode titled, "Return of the Archons", was about. A computer-run colony of people with a very stagnant culture that seemed to be more destructive than helpful. This episode, despite having some flaws, is probably one of my favorite episodes, not only because Mr. Spock looks very dashing in his cloak, but because it digs into what makes a human being alive.

Dashing Mr. Spock.

Society, by definition, is the aggregate of people living together in a more or less ordered community, and from what we know, Landru has not allowed the Betans’ society to thrive. Instead, he has allowed it to stay in this linear pattern, which is nothing more than the same routine every day. Well, that is except for one day, of course, during the Festival, where it seems you are allowed to do whatever (and whomever) you want, without Landru's instruction. But why is the culture so stagnant? That’s simply because Landru is a machine.

Our first glimpse of "Landru".

Throughout the episode, it is suggested multiple times that Landru is not human by Mr. Spock, and as someone who isn’t fully human, he should know. And by the end of the episode, Mr. Spock is right but also somewhat wrong. Landru was a human many years ago, but now he no longer exists as a living creature but is instead a computer, who may have his knowledge but not Landru’s wisdom. While Landru tried to save his people from the ruins of war, by having a machine input and output peace and tranquility above all, he created a machine that prohibited all human creativity and advancements. To put it simply, these Betans are not thinking for themselves as they have a machine telling them what to do and probably how to feel non-stop. It’s even stated by Mr. Spock, after Kirk causes the Landru machine to self-destruct:

“They have no guidance. Possibly for the first time in their lives.”

Free will is the basis of all of humanity. Without free will, we are nothing more than just robots. We are nothing more than what Landru was, awaiting the next input from a human. If you cannot think for yourself and rely on someone to tell you what to do, are you truly alive? That point was underscored by the confrontation between Landru and Kirk talked: Landru could ordered its men to kill Kirk or simply stop talking, but instead, Landru allowed Kirk to tell it what to do. Landru does not have free will, therefore relies on someone to tell it what to do.

Yes, a programmed society IS a dead society, for it contains no individuals. It can not grow from human mistakes. It will stay the same, because that is what it is programmed to do. It is programmed to give you the same result each time. A human can never give you the same result all the time, no matter what you tell them.

That’s why, to me this episode kept me thinking, even in the slower parts of the episode. And just for that, I give it my good old rating of 4.5 out of 5 stars.

But also for Mr. Spock in a smock.

Everything Old is New Again

by Janice L. Newman

“Return of the Archons” was a fun episode, but one that doesn’t hold together well if you look at it too closely. I had to wonder if the story was written to make use of sets and costumes Desilu had on-hand. If so, they did a decent job, making the transitions from Western Town to what looked like Castle Dungeon fairly convincing. Plus, it was fun to see the crew dressed in period costume even if, as The Traveler noted, this was inconsistent with prior episodes.

Garb and scenery weren’t the only things we’d encountered before. From music, to actors, to the very theme of the story, all of these were recycled from other episodes.

Setting aside the Enterprise crewmember regulars, at least one of the townspeople appeared in a prior episode: the old man Tamar, who dies at the hands of Landru’s enforcers, appeared as the illusory leader of the colonists in The Cage (or as most people will remember it, The Menagerie). Re-using actors is common practice, of course, but it’s always fun when one can identify someone that’s been seen before.

“Aren't you Vina's father?” “Of course not! Vina's parents are dead…I mean…Vina who?”

As for music, Star Trek commonly reuses themes written for the first few episodes of the show. I thought it particularly cleverly done this time, with the driving ‘encounter with the Fesarius’ music from the The Corbomite Maneuver used to back the violent ‘Festival’ scenes juxtaposed effectively against the eerie, wailing piece that begins with a descending half step that was first introduced in The Cage/The Menagerie (though viewers not privileged to see The Cage may have first encountered it in other episodes). Themes from several other episodes were interwoven throughout, but those two in particular stood out to me as interesting choices. I especially liked that the piece from The Cage, which has usually been used to introduce beautiful women who are viewed through a soft-focus lens, was instead used to underline how oddly the people of the planet were behaving.

And then there’s the thematic recycling. While it’s not a one-to-one match, there are definite resonances between Return of the Archons and What Are Little Girls Made Of?, the episode where Kirk encountered (and ultimately destroyed) multiple androids. Doctor Korby, or at least his android version, had envisioned a society where all people were turned into androids like himself. When confronted, he cried, “I'm the same! A direct transfer. All of me, human, rational, and without a flaw.” Contrast this with computer-Landru’s words: “I am Landru. I am he. All that he was, I am. His experience, his knowledge.” Consider, too, that computer-Landru built a ‘rational’ society of people who were little more than robots, fulfilling a similar vision to Korby’s dream.

Reusing and recycling can be good if it’s done with cleverness. Just as a skilled tailor can take an old dress and disguise it as a new one with a few alterations, changing the context can make costumes, sets, actors, music, and even themes feel like new and different choices. It’s a good cost-saving measure and an efficient use of what one already has on hand.

But like a dress that’s been altered too many times, sometimes the seams start to show. There were too many questions left unanswered in Return of the Archons for me to enjoy it as much as I’ve enjoyed other episodes. What exactly was the purpose of “The Festival” and how often did it occur? How wide was Landru’s influence – for example, were the people of “the valley” also under his control? (And if not, why did they not seek to free their neighbors from it?) Why were some people immune to Landru’s influence? Why was it so easy for Kirk to break Landru at the end (another parallel with What Are Little Girls Made Of?), despite the fact that his logic didn’t make much sense?

Dialectic at thirty paces

I can come up with answers to all of these questions, and I’m sure you can as well. Sometimes that’s the fun of shows like these: filling in the holes. But leave too many holes and a garment falls apart. I’m afraid that under closer scrutiny, Return of the Archons does just that, which is why I can only give it three stars.

Computer Dating

by Lorelei Marcus

There are many issues that come from a society run by a computer. Of course, there's the lack of will of its inhabitants, as Abby points out. But beyond that, there are serious logistical concerns. Landru's utmost priority is to "preserve the good of the body" or protect the community he is in charge of. He does this by assimilating every one of his citizens into a state of compliance, and then has them walk around all day greeting each other. "A simpler time" indeed.

Assuming there is no labor in this society, and all the infrastructure is produced and controlled by machines (perhaps using energy to matter food converters like we've seen on the Enterprise), then the biggest logistical issue in Landru's society is the production of more people.

(Note: the beings we see are not actually humans but aliens on their own planet with a coincidentally similar biology to us. Despite this, those from the Enterprise frequently refer to them as humans and rejoice in the destruction of Landru because it makes the society more human. Now who's doing the assimilating?)

I believe Landru's solution to the (need for) population issue is Festival Day, one of the great mysteries of the episode. A time when the young adults of the town (the elderly are excused) riot in the streets, breaking windows, setting fires, and generally committing acts of lust and violence alike. It's a horrific display, and one that contrasts jarringly with the normal tranquility.

Kirk's hotel overlooks the Sunset Strip.

There are two explanations for Festival, one being that, while Landru has an immense capability to pressure human minds into subservience, inevitably there will be some, over time, whose suppressed emotions boil over and cause outbursts (or perhaps even turn them into resisters). The Festival allows them to get these out of their system in a directed fashion.

The second explanation: as far as I can tell, there are no interpersonal relationships in this culture, which would lead to a distinct lack of intimate sexual encounters.This would lead to extinction. So Landru kills two birds with one stone, allowing its people to indulge their baser desires on Festival, and nine months later, producing the next generation for Landru to influence. An elegant solution to an inelegant problem. Something that could only be conceived by a machine.

I personally have no opinion on the rightness of Landru's programmed culture, but I do feel the concept had and has a lot of potential for a science fiction setting. I wish Captain Kirk had taken a little more time to explore and understand his surroundings before deciding that destroying them was the only option. Perhaps this episode will inspire more stories with a similar premise, but more fleshed-out worlds. We can but hope.

Three stars.

When you assume…

by Erica Frank

Sigh. Once again: An entity with godlike abilities controls a society where a veneer of peacefulness hides an underbelly of fear and violence. This time it's a soulless computer, not an "evolved" being—but it still treats humans as playthings. Two clichés for the price of one!

I suppose it's difficult to write about benign beings with godlike powers; if they exist, wouldn't they be out helping people and making the galaxy a better place? How would the Enterprise even encounter them, except in a setting like Shore Leave – "here's our vacation resort; enjoy?" But I am so very tired of the variations on "actually, ESP stands for Evil Supremacy Powers."

Setting aside the hackneyed science fiction elements and focusing on the story itself, I thought Kirk missed his mark, and more than once.

When he spoke to Reger and Marplon, trying to convince them to help him fight Landru, he tells them to set aside their fears and "start acting like men!"…as if they were actually humans who grew up in a human culture. Instead, they are aliens who just look like humans, raised in a culture where, for thousands of years, people who show any resistance have their memories and personalities wiped, and become "of the body"—forever lost to their loved ones.

They don't have a context for bravery. They have no stories of heroes to inspire them. They have a whispered legend: Someday, the "Archons" will return to save us. But they have no plan for assisting. Defiance, for them, is secrets and stealth, not confrontation. Yet Kirk expects them to act like human men from a culture that values heroism.

“Did we say 'resistors'? We meant 'rejoicers!' We love Landru!”

Later, Kirk told Landru that the society he'd built wasn't peaceful, but stagnant, that people need creativity and free will. That's true—but he failed to mention the "Festival" of violence and destruction. Why didn't he mention Tula's injuries, the rubble in the streets, the terror and carnage of the twelve hours of Festival? Those seem like much stronger counterpoints to Landru's claim of a "perfect and tranquil" society.

However, even though I sighed at the mind control, and may have yelled at the screen during Kirk's talk with Landru, I enjoyed most of the episode. The blend of an apparent 19th-century culture with "lawgivers" who look like medieval monks was delightful, and I'm fond of "religious kook" language, even when it's obviously forced. Maybe especially then—I did like Kirk's pretense of being "of the body" near the end of the episode.

Three and a half stars. Fun to watch; even more fun to critique.

A Perfect Society—for Whom?

by Jessica Dickinson Goodman

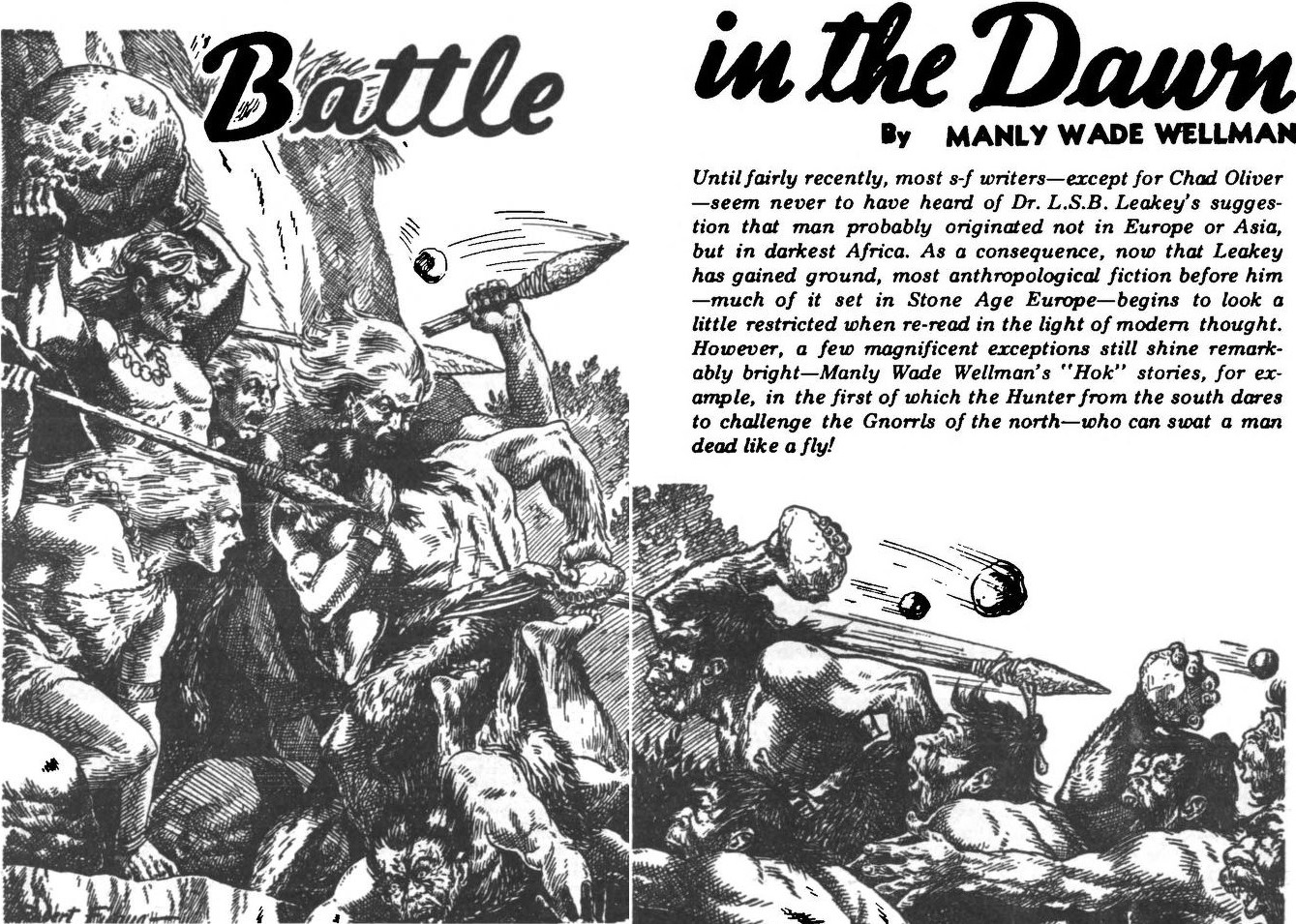

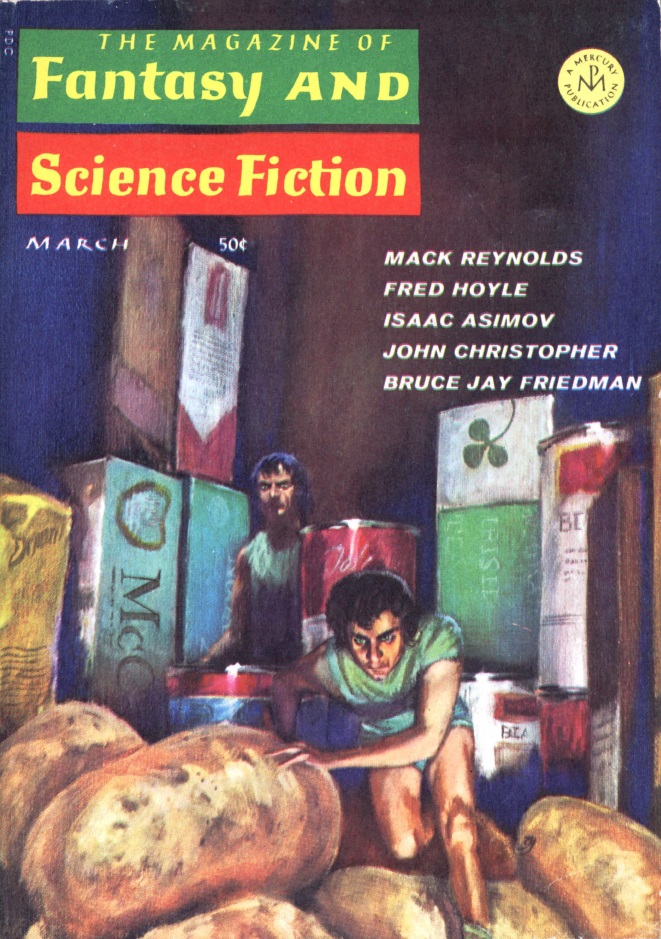

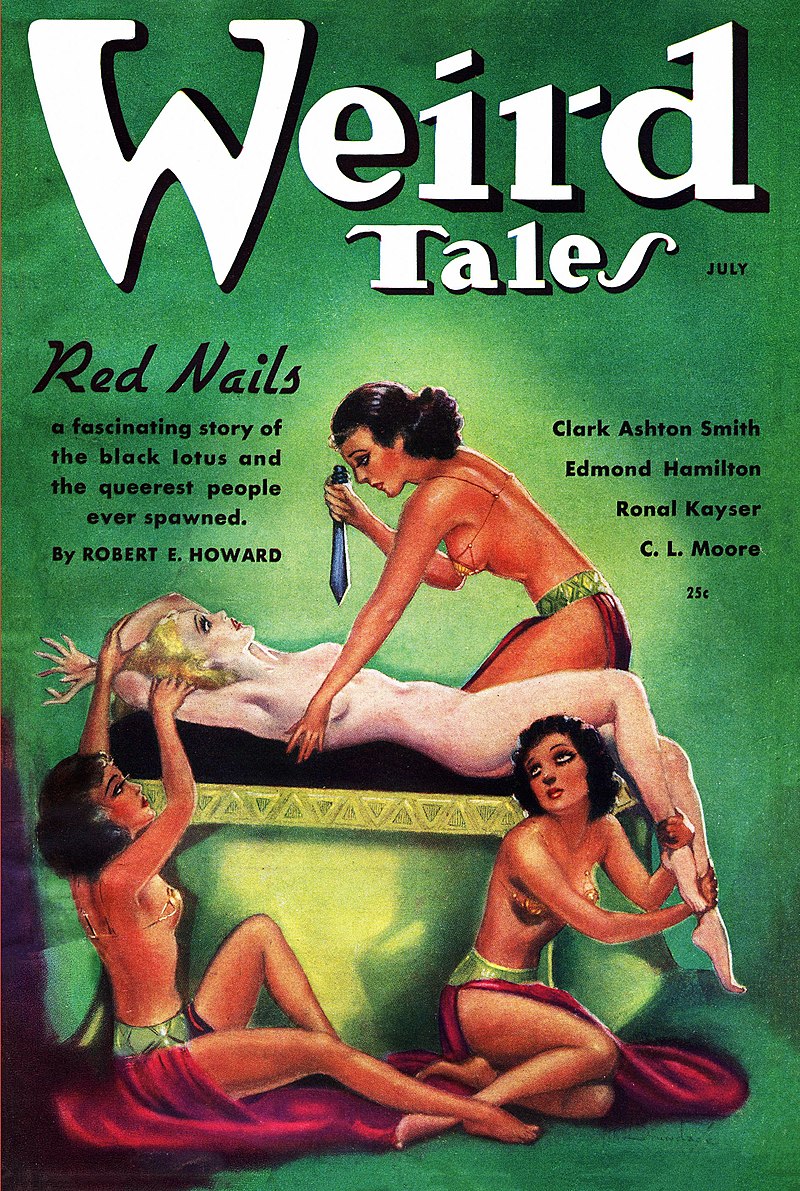

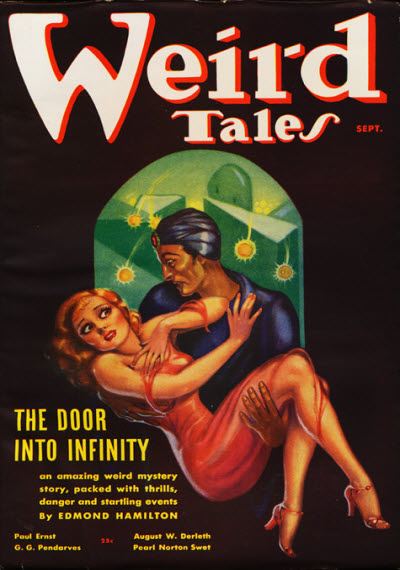

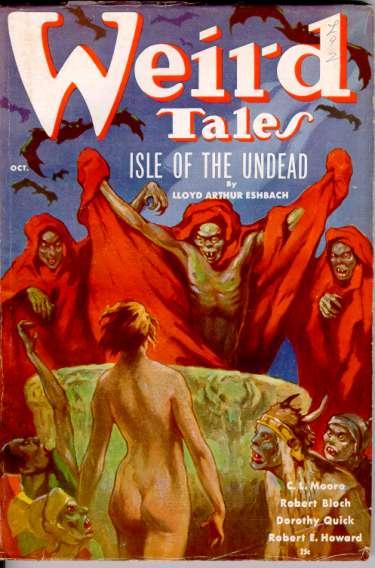

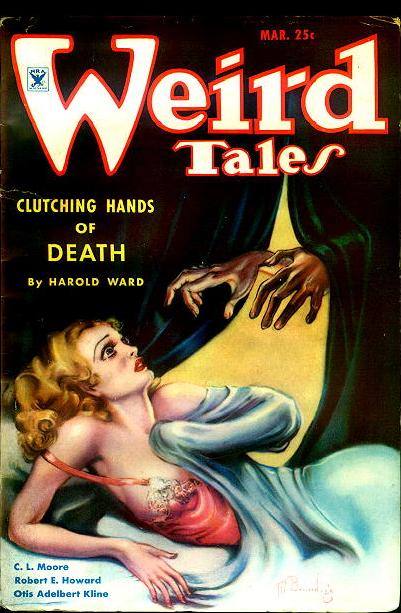

The "Festival" scenes from "Return of the Archons" reminded me of a piece by Miriam Allen deFord in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction back in 1956. She was responding to a Saturday Review column by Dr. Robert S. Richardson, where he argued women should absolutely be included on future missions to Mars – as sex toys for the male astronauts. Ms. Allen DeFord deftly picks apart Mr. Richardson's argument, redolent with "subconscious male arrogance," piece by piece, in an article I have laid out in my feminist scrapbook; but it was her successful shredding of his argument that women are emotionally unsuitable for space travel that I thought of most during this week's Star Trek episode.

Women. So emotional.

Ms. Allen deFord writes:

"The notion that women are inherently more emotional and excitable than men is a hoary myth that belongs back in the days of the 18th century 'vapors' and Victorian swoonings. Actually, the convention that induces men to repress every indication of emotion makes neurosis more prevalent among them than among women."

Men. The picture of mental stability.

That see-sawing between repression and violent emotional excitement formed the core of Landru's unbalanced world. But the near-total invisibility of women on Beta Three – with the exception of Tula, the daughter of a saloon-keeper who seems to only have existed to be brutalized during the Festival – was exactly the kind of society that Dr. Richardson had envisioned humanity creating on Mars. One where women's only roles are to be carried off by men, screaming.

Landru takes Beta 3 back to a simpler time: the Neolithic.

I like Ms. Allen deFord's vision better, because it reminds me of the world we are usually treated to on the Enterprise. One which is composed of, as she says: "a bisexual instead of monosexual staff of prioneer observers, investigators, and technicians." It is a future where women are not toys or victims, but living people who sing, study, lead, organize, and live. Where: "Women are not walking sex organs. They are human beings. People, just like men."

Landru's major failure in this episode wasn't just assuming that the best world for his descendents would be one characterized by dull emotional repression, punctuated by scarlet periods of neurotic violence; it was designing a world where women held no meaningful power and were confined to roles which profoundly limited their human potential far below the men in their society.

Here's hoping in the next episode, Lieutenant Uhura gets more than one line and we go back to having fully human women alongside us on our journeys to the stars.

If you squint, you can almost see Uhura in this episode.

Three stars.

PS: I wish some brave soul would collect and republish Ms. Allen deFord's essay and other pieces from her era so more people could enjoy her incisive wit and colorful prose; maybe pair it with some women-centered fiction by Mari Wolf, Alice Eleanor Jones, or Evelyn E. Smith.

Tonight at 8:30 PM (Eastern and Pacific), Hollywood Palace presents Ricardo Montalban and his Amazing Supermen!

Come join us – here's the invitation!

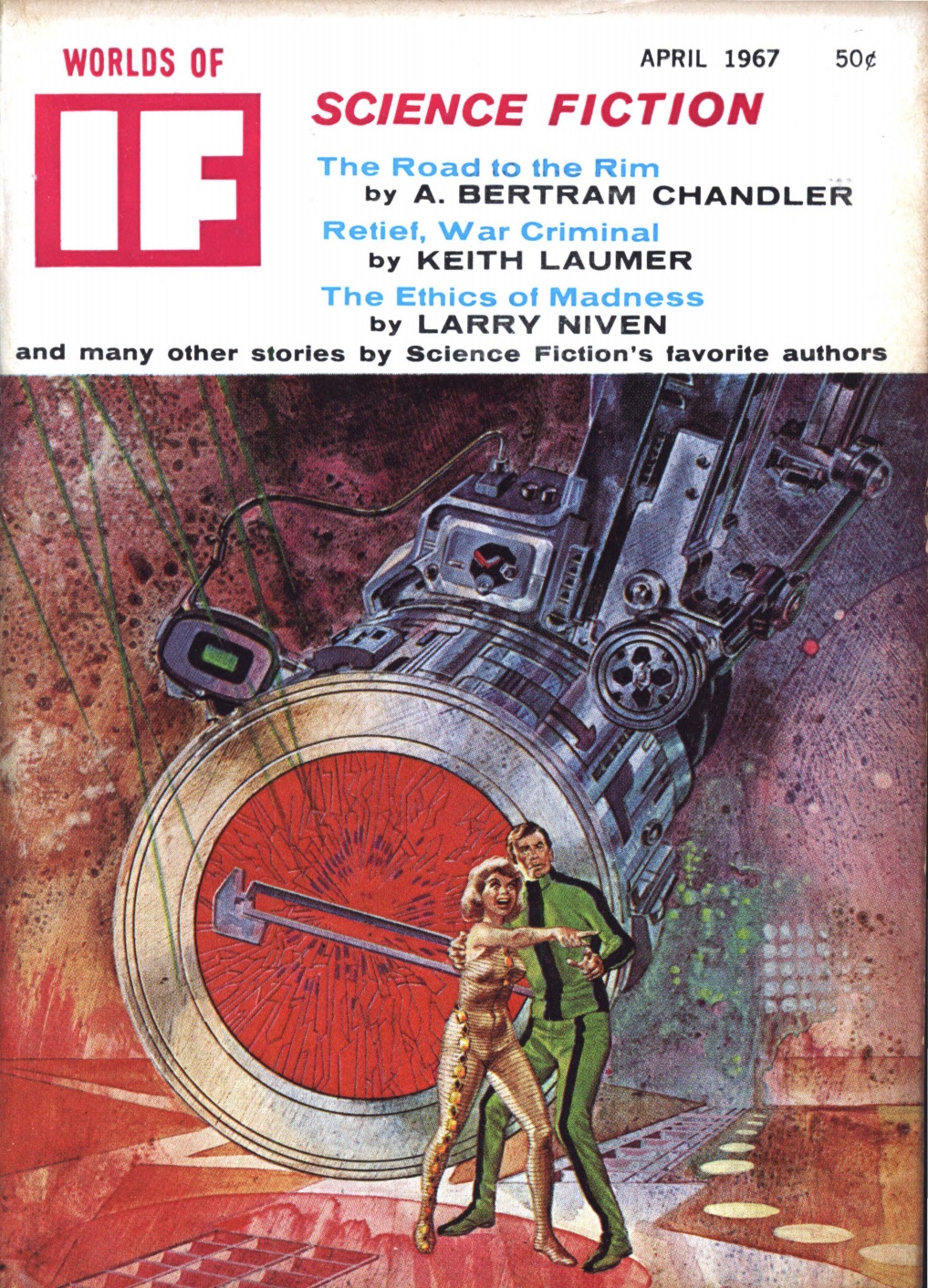

![[March 4, 1967] Mediocrities (April 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IF-Cover-1967-03-672x372.jpg)

![[March 2, 1967] (<i>Star Trek</i>: "A Taste of Armageddon")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670302title-672x372.jpg)

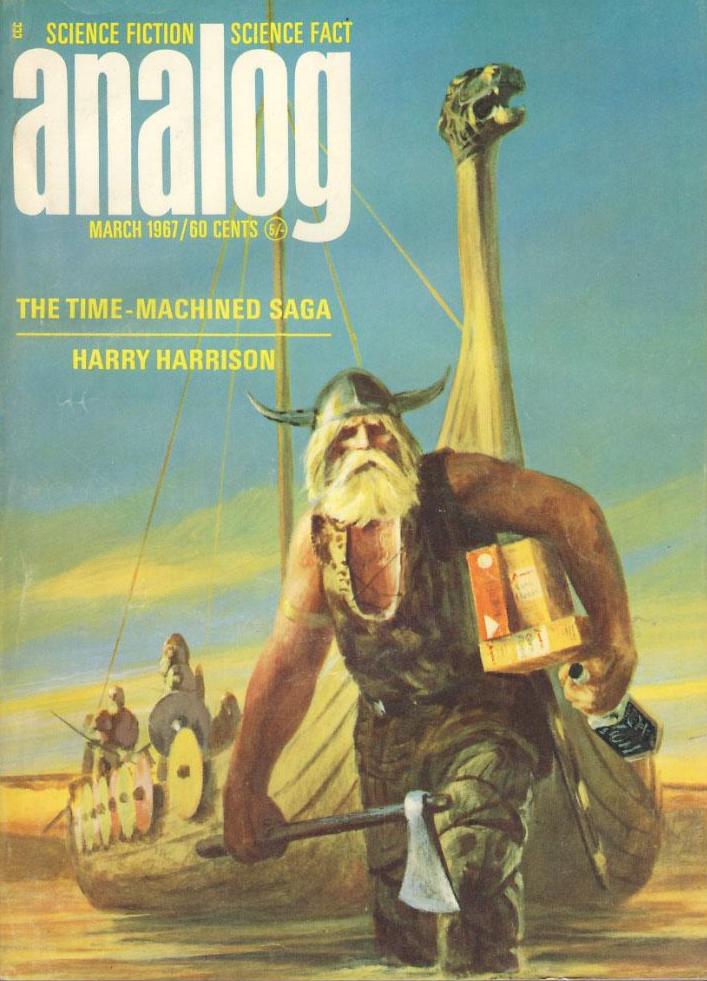

![[February 28, 1967] The Big Stall (March 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670228cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 24, 1967] Changes Coming (<i>New Worlds and SF Impulse</i>, March 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/New-Worlds-March-1967-672x372.jpg)

![[February 22, 1967] Where some (super)men had gone before (<i>Star Trek's</i>: "Space Seed")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670222title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 20, 1967] To Ashes (March <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670220cover-661x372.jpg)

![[February 18, 1967] Six! Count them — Six! (February Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670218covers-672x372.jpg)

![[February 16, 1967] The People's Choice (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Return of the Archons")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670214title-672x372.jpg)

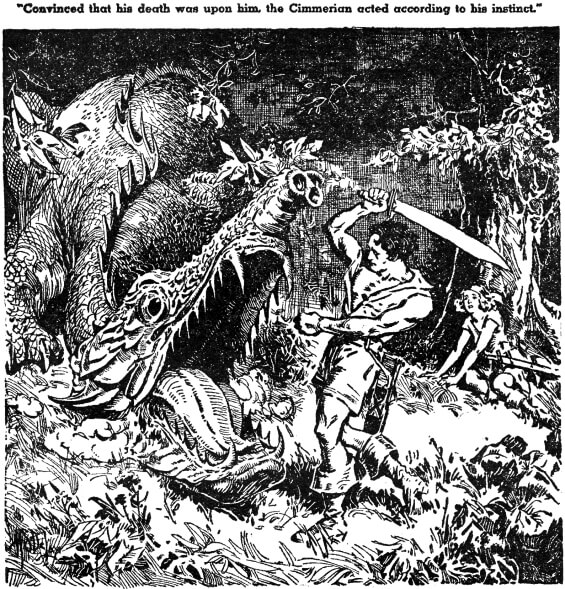

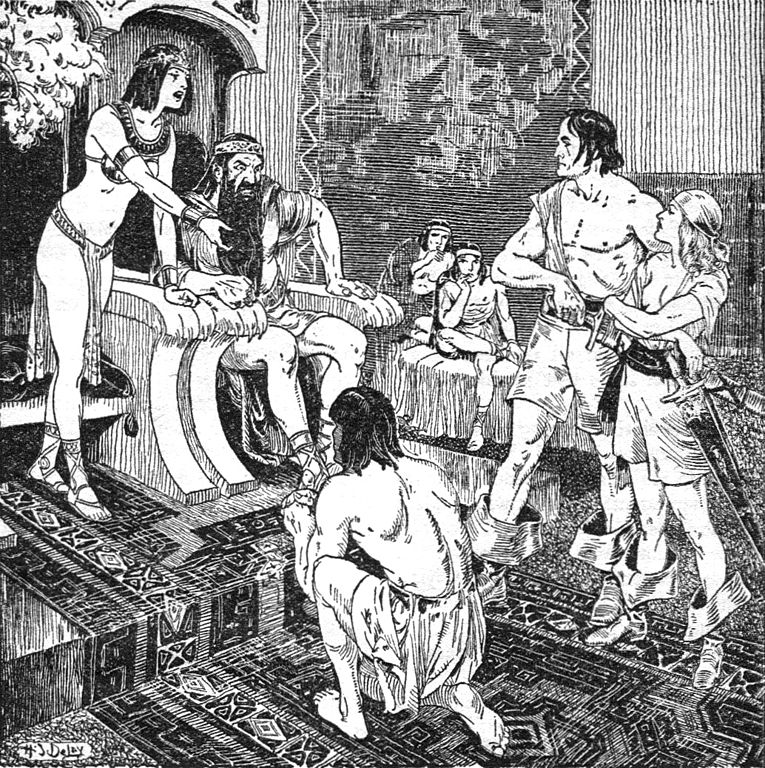

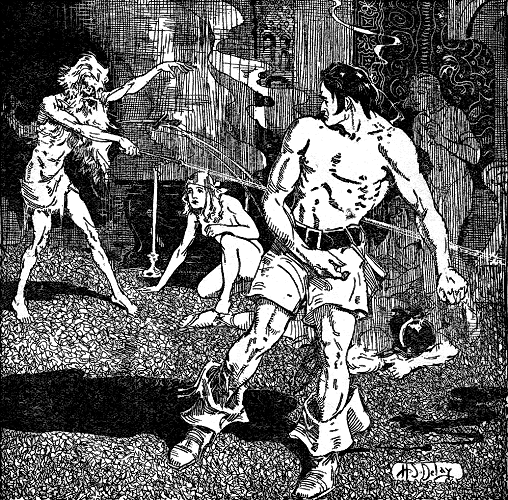

![[February 14, 1967] Three Facets of Conan: <i>Conan the Warrior</i> by Robert E. Howard](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/02conan_the_warrior.webp)

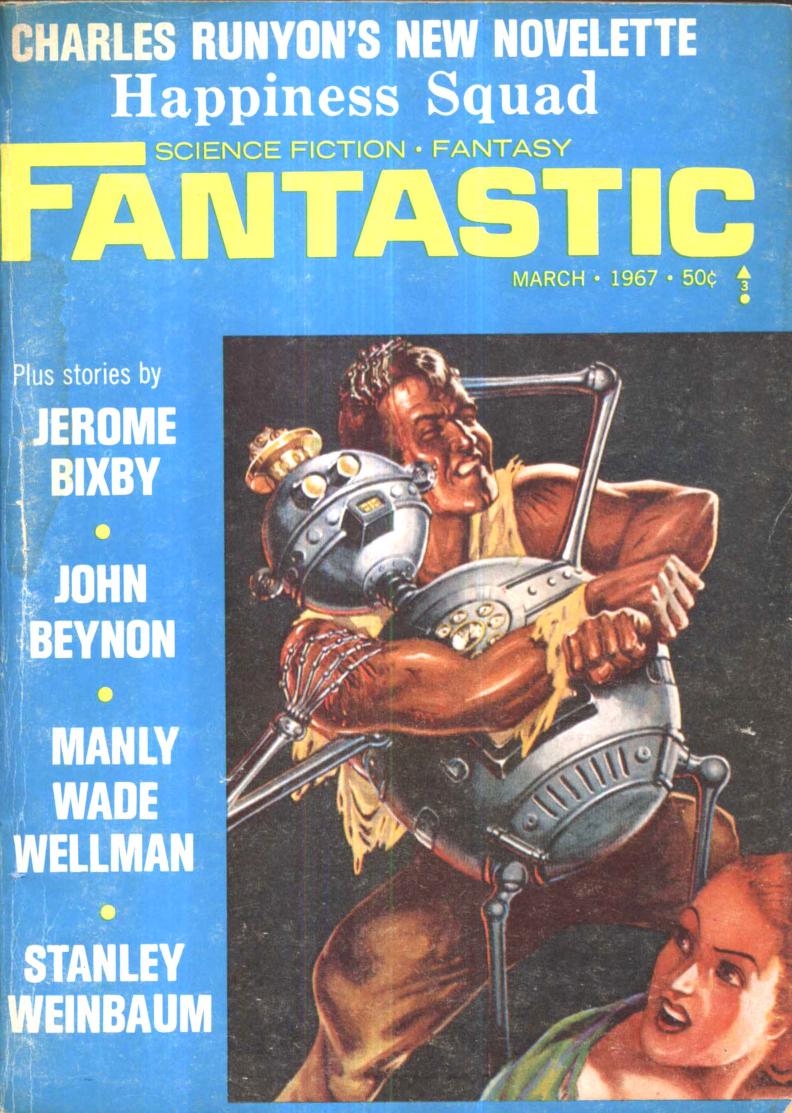

![[February 12, 1967] All's Fair in Love and War (March 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Fantastic_v16n04_1967-03_LennyS-cape1736_0000-2-672x324.jpg)