I have lamented for some time that we've been at a nadir of female participation in our peculiar genre. If this month's clutch of books be any indication, that trend is finally reversing, to the benefit (for the most part) of all of us science fiction readers!

by Victoria Silverwolf

Wordplay

Two new science fiction novels arrived this month with one-word titles that don't show up in my dictionary. No doubt that's meant to intrigue the potential reader, and create the sense of strangeness associated with much SF. Let's take a look at them and see if we can figure out what the titles mean.

Restoree, by Anne McCaffrey

Anonymous cover art.

Sara is a very ordinary young woman, maybe a little less content with her life than most. She considers herself unattractive, and is particularly sensitive about her large nose. She runs off from an unhappy home to take a job in New York City.

While walking through Central Park one night (not a wise thing for an unaccompanied woman to do, I'd think) she is abducted and taken aboard an alien spacecraft. The opening of the novel is a chaos of strange and disturbing sensations, so we don't really figure this out for a while, but it becomes clear later.

In a way that isn't explained until late in the book, she winds up in a

new body. For some time, she's in a dazed, zombie-like condition, only slowly coming to full awareness. The good news is that she's beautiful, with golden skin and a perfect nose. The bad news is that she's enslaved as a sort of nursemaid to a fellow in a mindless state.

Eventually, she figures out that the fellow has been drugged into catatonia by the bad guys. She helps him return to normal by reducing the amount of drugged food he consumes. The two escape from the hospital/prison and a tale of palace intrigue and space opera adventure begins.

The plot gets pretty complicated, and there are lots of characters with odd names, so I got lost at times. (The drugged man's name is Harlan, by the way; a reference to one of the author's fellow writers? Anyway, he's got the only name I've ever seen before, other than the heroine's.)

Suffice to say that Sara is on another planet, although the inhabitants are completely human. Harlan is the Regent for the planet's young Warlord. The bad guys drugged him, faking it as insanity, in order to control the government in his place. Add in aliens that Harlan's people have been fighting for millennia and rival factions for the throne. A further complication is that Sara has to hide the fact that she's a restoree (there's that word!) or she is likely to be killed as an abomination.

Besides all this science fiction stuff, there are a lot of romance novel aspects to the book. The beautiful, virginal heroine and the dark, mysterious hero fall in love, finally consummating their passion in sex scenes that are far from explicit. I also found a fair amount of subtle humor in the novel, as if the author has her tongue firmly in her cheek. What the evil aliens do to the people they capture stirs in a bit of gruesome horror as well.

The characters, for the most part, are either all good or all bad. The only ambiguous one is the brilliant physician who gave Sara her new body, in the forbidden and universally reviled procedure that made her a restoree. (If he hadn't, she would just be dead.) He does seem to be genuinely concerned with healing the afflicted, but he also works with the bad guys.

Kind of a silly book, really, but mildly entertaining if you turn your brain off. It's the author's first published novel, so let's just say that she shows promise.

Two stars.

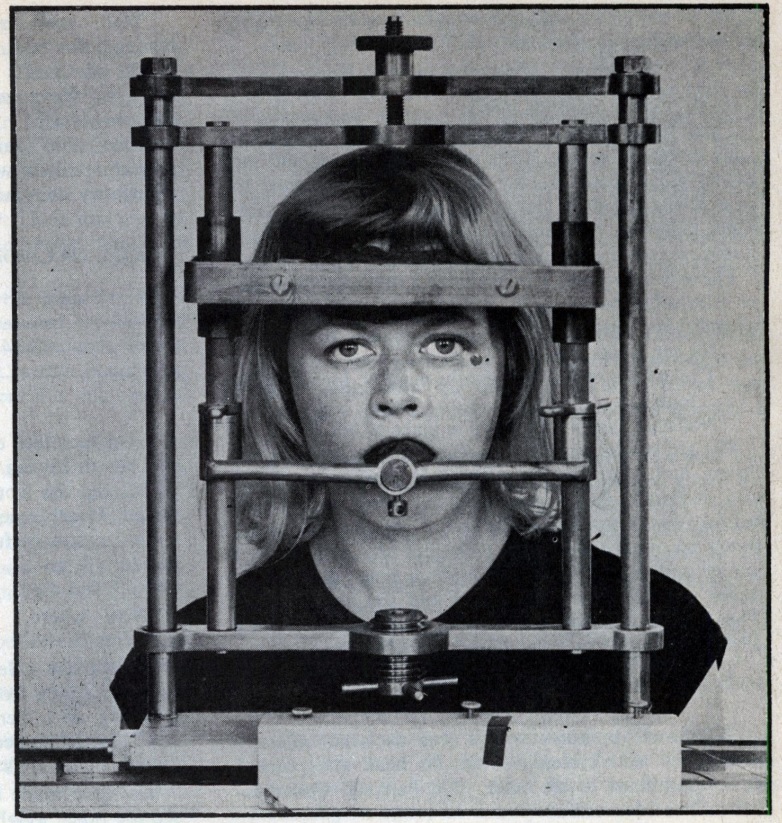

Croyd, by Ian Wallace

More anonymous cover art.

The explanation for the title is simple enough; Croyd is the hero's name. He has no other, as far as I can tell.

Croyd is some kind of agent for the galactic government. He is also a Van Vogtian superhuman, with a brain that allows him to do things like go back and forth in time. While waiting to hear the details of his latest assignment, he saves a lady in distress from an abusive man.

There's a lot more to the woman than he realizes. It seems that an alien from another galaxy, bent on conquering the inhabitants of the Milky Way, has her mind inside the woman's body. Next thing you know, her mind is inside Croyd's body, and his is inside the woman's.

The woman's mind is still inside her body as well, so she and Croyd share it as they track down the alien who stole Croyd's body. Meanwhile, a gang of beatnik terrorists are planning to send the asteroid Ceres crashing into Nereid, one of Neptune's moons, where there's a government base. The alien in Croyd's body has to deal with this, to convince people that she's really Croyd.

Things get really complicated. There are alien agents among the government staff, with the ability to hypnotize people into turning against humanity. There's another group of aliens that wants to destroy the entire Milky Way rather than conquer it. Both Croyd in the woman's body and the alien in Croyd's body have to fight their nefarious scheme. There's even a second Croyd mind that shows up inside his purloined body. This one is a stupid brute, intent only on animal pleasures.

With all this going on, and characters rushing back and forth in space and time, this is definitely a wild roller coaster ride. I didn't believe any of it for a second. If McCaffrey's book often has the feeling of a stereotypical woman's romance novel, with science fiction trappings, Wallace's frequently seems like a stereotypical men's adventure novel, with the same decorations.

Two stars.

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

With the New Wave such a strong force in British science fiction at the moment there is a real blurring of the boundaries of what is speculative and what is literary experimentation.

If they had not come of Science fiction publishers and\or from science fiction authors would we consider Squares of the City, Greybeard or Ballard’s cut-up tales to be speculative? By the same token if Fowles’ Magus, O’Brien’s Third Policeman or Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita had been published as Ballantine Paperbacks from Cordwainer Smith or Daniel Keyes, would they be on the Hugo Ballot?

This leads into probably one of the most interesting edge cases of recent years, where the author says she had no intention of writing science fiction but it is hard for the SF community to see it as anything else:

Ice, by Anna Kavan

In contrast to some recent writers, Kavan’s move into the speculative realm is not as much of a leap. She has been writing since the twenties and her works have often made use of experimental and surrealist techniques, commonly looking at madness and incarceration.

As anyone who has read the stranger side of science fiction, such as Philip K. Dick, these kind of ideas are often played with in the speculative space. However, in this work it definitely feels like she walks over the 49th parallel into SFnal Canada.

In Ice we follow our unnamed protagonist (no one has names here) through a world where society is collapsing under the weight of a frozen disaster. Our narrator seems to be in pursuit of a young woman near the start but the full motivations remain obscure as, even though written in the first person, it is narrated in a very matter of fact style.

In many ways this reminded me of Ballard’s elemental apocalypses, where The Drowning World flooded the world and The Drought boiled it, this one has frozen it. And all involve the characters moving through the disaster riven Earth in a dream-like state, as we get to see insights into their state of mind.

However, where Ballard does more direct exploration of his inner-space, Kavan keeps everything very cold and clinical, written in sharp fragments such as this description of the aftermath of a rape:

Later in the day she did not move, gave no indication of life, lying exposed on the ruined bed as on a slab in a mortuary. Sheets and blankets spilled on to the floor, trailed over the edge of the dais. Her head hung over the edge of the bed in a slightly unnatural position, the neck slightly twisted in a way that suggested violence, the bright hair twisted into a sort of rope by his hands.

There is no mention of our narrator’s feelings on this, it is treated in a disassociated manner, as if he is outside the events being described. This in itself gives us insight, but predominantly by the absence of explanation than by the paucity of it.

Yet, it remains dreamlike in another way, for it follows through in a manner that feels coincidental and directionless. They move between scenes in a way that often led me to look back if I had missed anything. In addition there are regular hallucinations throughout, meaning that we have extra questions as to the reality of what we are seeing.

But I believe this is the point: we are meant to feel isolated and abstracted, just as the protagonist does. To see what we as the reader are appalled and terrified by this world, yet we see someone completely numb to it all as our guide.

I could take you through various sections but really it is one of those books you need to experience, to delve into the atmosphere and feelings (or rather lack thereof) in order to truly understand.

A very high four stars.

by Gideon Marcus

Bringing up the Rear

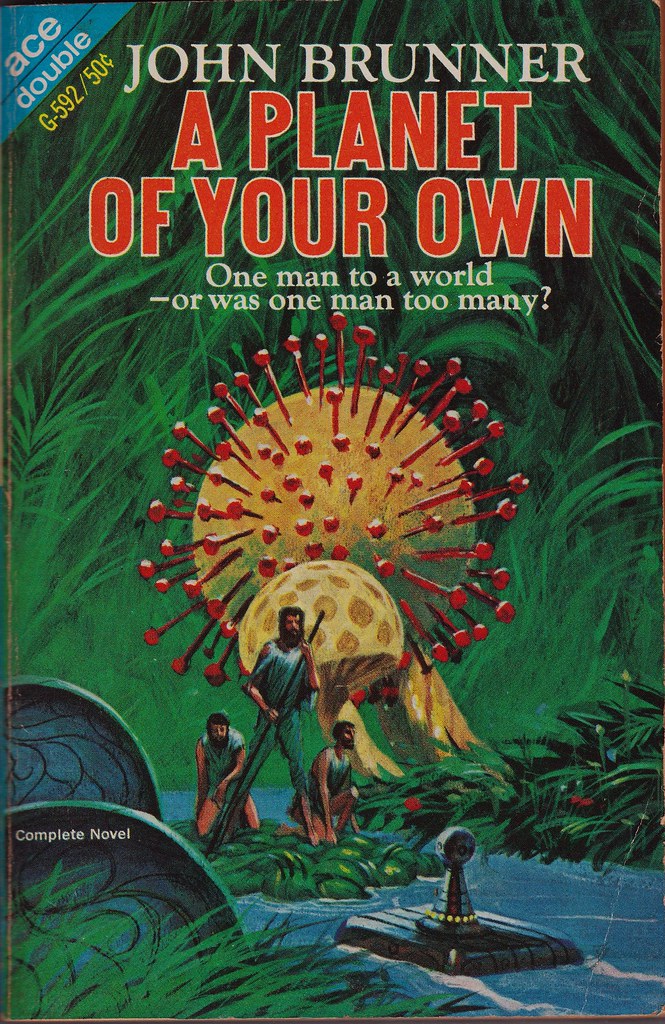

Ace Books, regular as clockwork, releases a monthly double dose of adventure in the form of the luridly composed Ace Doubles. In the past, these bundled short novels had a reputation for being rather shallow and adventure-focused, while also being subject to the mercurial editorial whims required to ensure the stories fit in the prescribed lengths. Over the last few years, however, these volumes have become some of my favorite sources of entertainment, and they've launched the careers of many a new and promising author. This time around, we've got a veteran paired with a newcomer:

The Winds of Gath, by E.C. Tubb

Earl Dumarest awakens from cold sleep several days prior to his destination. He is one of the fortunate ones: 15% of the interstellar travelers who take Low Passage on a starship never revive. But Dumarest's luck ends there–instead of being dropped off at Broome, he must debark on the hell planet of Gath. On that tidally locked world, the Low Passage travelers are trapped without sufficient funds to leave, exploited by the Resident Factor of Gath despite the efforts of the local enclave of the Church of Universal Brotherhood.

What fuels the economy of this blighted planet? It is the winds that blow from the baked day side to the frozen night side. As they whistle along twilight mountain ranges, they set up resonances in the human mind, facilitating all manner of hallucinations: some pleasant, some insanity-inducing.

This natural phenomenon is the least of Dumarest's troubles as he has been plopped down into a budding conflict between the Matriarchy of Kund, the cruel Prince of Emmered, and other miscellaneous galactic forces. Can he thread the needle before the looming tempest envelops them all?

Truth be told, I was not expecting much from E.C. Tubb, a writer who almost invariably merits three stars. Even more so as the story reminded me strongly of Dune, with its sweeping setting, frequently shifting viewpoint, and its almost mythological character. The problem, of course, is that Dune was also a three-star tale for me.

So I was quite surprised that this tale grabbed me by the throat and did not let go until I finished, quite soon after I started. I think the main reason Tubb succeeds where Herbert does not is that Tubb can write! There are few wasted words, and his prose is sensual and visceral (perhaps he overuses "blood-colored" a touch; crimson would do occasionally). If Dumarest is a bit too superhuman, he is at least consistent in his abilities, and the limitations thereof. And such a vividly drawn world–it is clear that Dumarest will have more adventures in the future.

Four stars

Carl Race is a Federation junior ecologist brought into investigate an agricultural blight on Cheiron. The garden-like world is home to a race of primitive but industrious centauroids working with the private enterprise Consolidated Enterprises (humorously abbreviated to "Con En"). There is concern that Con En caused the global catastrophe, which threatens the planet's legume and honey industries, potentially destroying the entire ecosystem. Should Con En lose its contract to trade with the Cheironi, its rival, Trans-Galactic, will swoop in.

Very quickly, Carl, with the assistance of a human teacher, Marcy, and a precocious Cheironi teen, Nubi, determine not only that the blight is artificially caused, but that there is a nefarious conspiracy involved. Much rushing around, near-miss assassinations, chase scenes, scientific explanations, and spelunking ensue. Don't worry–it's got a happy ending.

Author Juanita Coulson is probably better known to the world as half of the editing team of Yandro, a prestigious fanzine that has garnered nearly a dozen Hugo nominations and one win. This is her first foray into novel writing, and she's not nearly as polished as Tubb. The first 20 pages are quite rough sledding, and probably could have been pared down to perhaps a page. In fact, the whole first third is quite padded, and I have to wonder if this was an editorial decree to fill space (this particular Ace Double has very compressed pica, resulting in more words per page). But I stuck with it, and ultimately I found the book to be decently enjoyable. It feels pitched at a much younger audience, what was once called "juvenile" and is now coming to be termed as "young adult". You will probably guess the phenomenon that is the culprit before it is described, but that's fine. One should be able to solve a mystery from the clues provided.

I appreciate that Marcy is vital to the plot and Carl clearly finds her attractive, but no romance develops between the two leads. The aborigines are depicted as equals to humans (with good and bad examples of the species), which I would expect as Coulson has been a strident civil rights booster since her college days in the early 1950s.

So, three stars, and congratulations Juanita!

![[September 10, 1967] Women's liberation! (September 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/670910featured-672x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1967] New York, New York! (the 25th World Science Fiction convention)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/670906hugo-350x372.jpg)

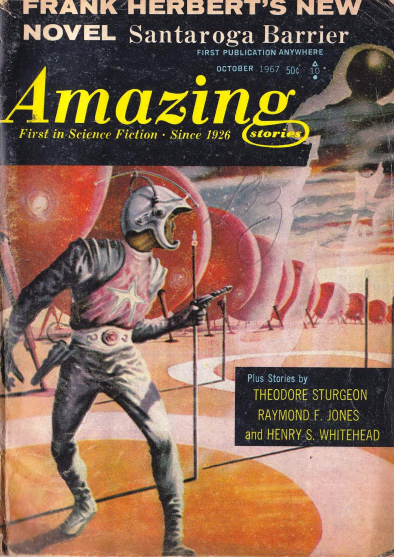

![[September 6, 1967] New Look, New . . . ? (October 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/amz-1067-cover-394x372.png)

![[September 2, 1967] Of Genies and Bottles (October 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IF-Cover-1967-10-672x372.jpg)

William C. Foster, the chief American representative to the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament.

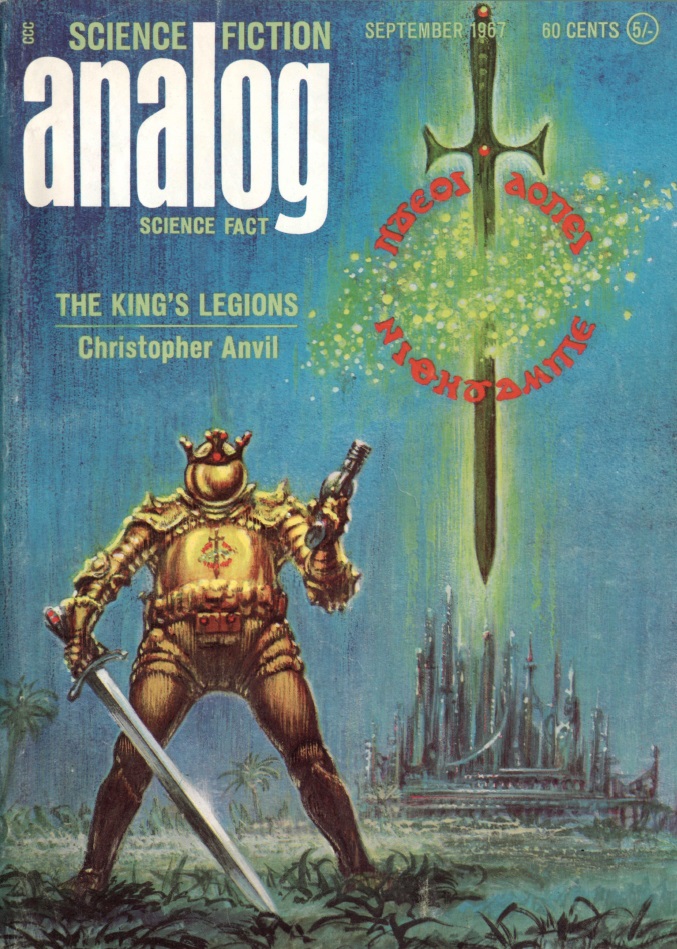

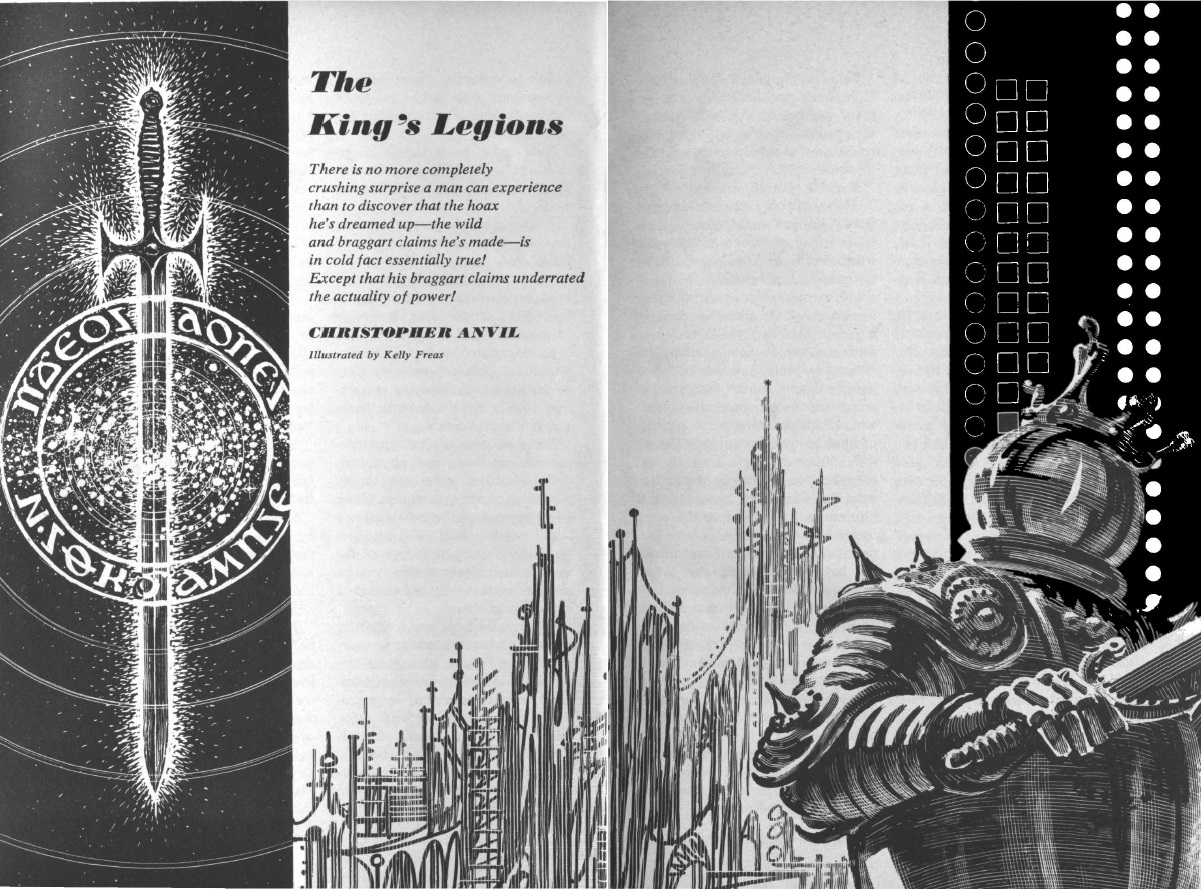

William C. Foster, the chief American representative to the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament. The art is intriguing, but none of this happens in Hal Clement’s new novel. Art by Castellon

The art is intriguing, but none of this happens in Hal Clement’s new novel. Art by Castellon![[August 31, 1967] I wouldn't send a knight out on a dog like this… (September 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670831cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 26, 1967] The Shock of the New II – Sex and the Modern British SF Reader <i>New Worlds</i>, September 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/New-Worlds-cover-Sept-67-672x372.jpg)

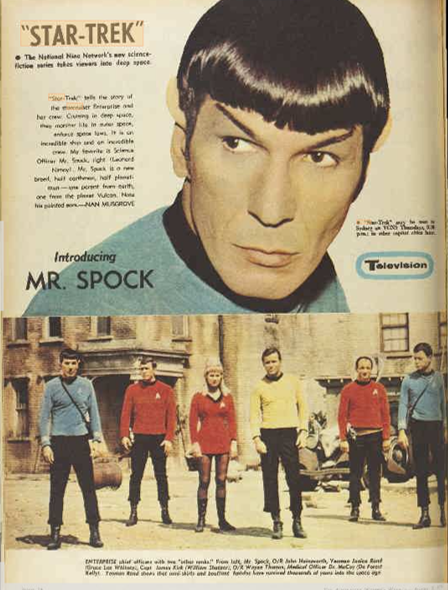

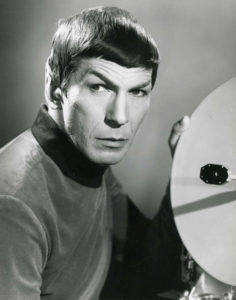

![[August 22, 1967] Boldly Going Down Under (Star Trek, Spies and space in Australia)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AWW-ST-448x372.png)

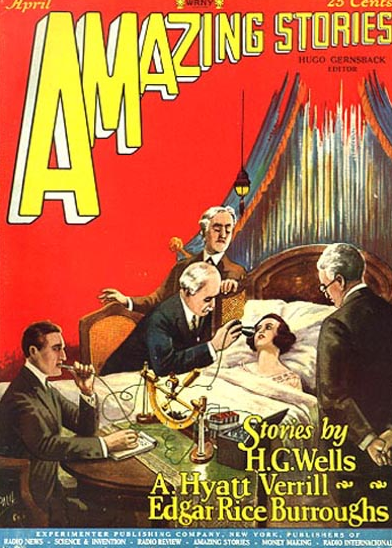

![[August 20, 1967] Hugo Gernsback, 1884-1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/gernsback-1929-486x372.png)

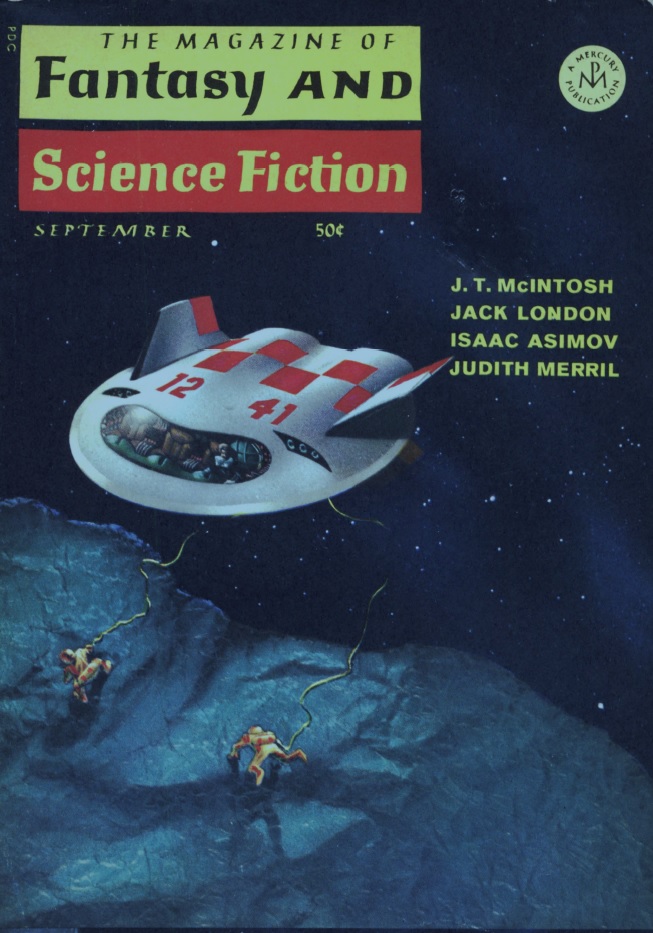

![[August 18, 1967] The Best and the Brightest? (September 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670818cover-653x372.jpg)

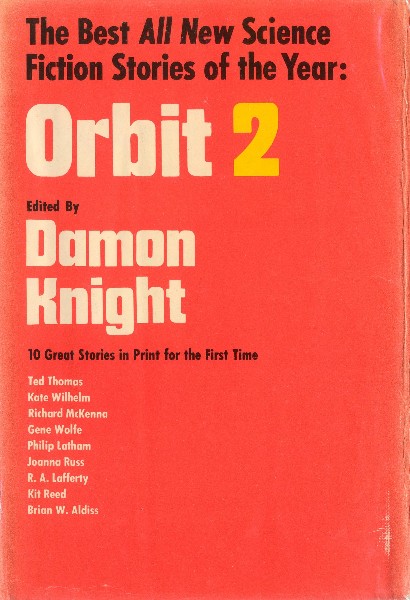

![[August 14, 1967] She Does Everything For Me (<i>Orbit 2</i> by Damon Knight)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670816cover-410x372.jpg)