by Gideon Marcus

Unusually for the Galactoscope, our monthly round-up of new science fiction publications, we're starting this article with a stop press. It's simply too big an item to ignore.

If you read the papers this morning, you know the big news was that the Mets played the winning game of the World Series last night, against the Orioles. Competing for inches on the front page was the largest, the most coordinated, the most widespread anti-war demonstration this country has yet experienced.

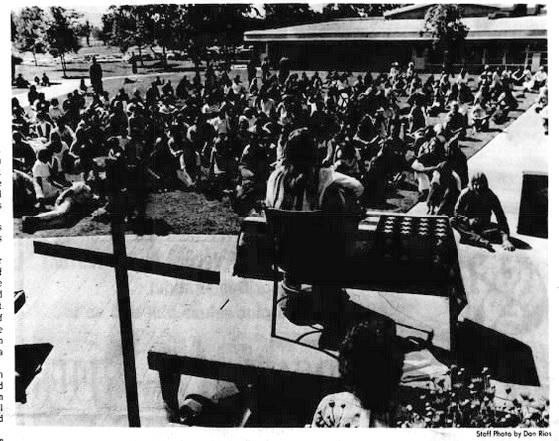

Demonstrators in Washington

One million people, in every state of the union, participated in Vietnam Moratorium Day. Originally planned as a nationwide strike, instead, attendees made highly their protests highly visible—and peaceful. A quarter of a million marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in the nation's capital, echoing Dr. King's march on Washington in 1963. 100,000 gathered in Boston, with similar numbers protesting in New York (where Mayor John Lindsay is rumored to have given tacit support) and Miami. My local rag reported that there were counter-protests, too, but I have to wonder how big they were.

Closer to home, 1,500 gathered in Los Angeles to burn their draft cards. And at Palomar Community College, just ten minutes from my home, hundreds of students gathered for a "Teach-In". When word got out that protestors might take down the flag in front of the student union, a squad of football players was stationed at its base. No altercation occurred.

Protestors at Palomar

Will this demonstration alter the course of a war, which has killed tens of thousands of Americans and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese? A spokesman for Richard Milhouse Nixon said last night, "I don't think the President can be affected by a mass demonstration of any kind." Comedian Dick Gregory retorted to the crowd in New York, "The President says nothing you kids do will have any effect on him. Well, I suggest he make one long-distance call to the LBJ ranch. "

Card-burners in Los Angeles

In any event, this may be just the first salvo fired in a peace offensive. Washington protest organizer Sam Brown said last night, "If there is no change in Vietnam policy, if the President does not respond, there will be a second moratorium."

And now on to book news—are this month's science fiction titles as noteworthy?

By Mx Kris Vyas-Myall

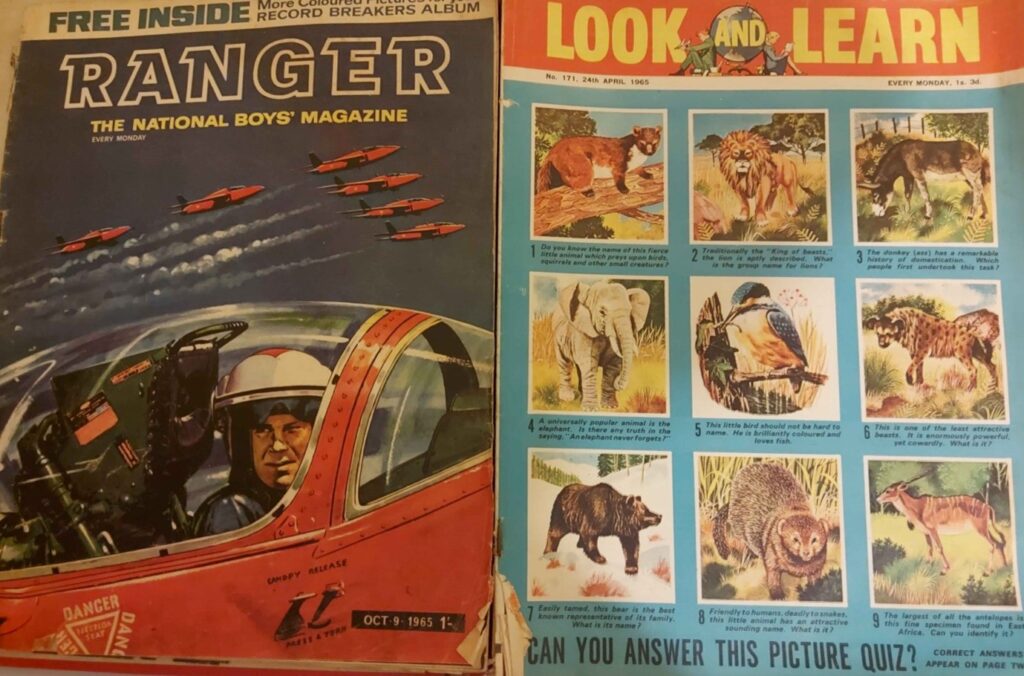

Heartease by Peter Dickinson (as serialized in Look and Learn)

Copies of Ranger and Look and Learn from my collection inside the official binders

Regular readers of the Journey will probably know I am a big fan of British comic books. They may even recognize the name Look and Learn due to it containing the multi-Galactic Star winning Trigan Empire (formerly of Ranger).

However, I have not talked much about Look and Learn itself. It is by far the most expensive comic book on the market at 1/6-, almost triple the price of your standard copy of June or TV Century 21. In spite of this it has retained a significant market presence by presenting itself as an educational magazine for young people, in contrast to the naughtiness of Dennis the Menace, or the pulp space adventures of Dan Dare.

This, however, is not merely a trick. They have both some of the best comic strips on the market and non-fiction articles–better than you see in most magazines aimed at adults. Looking at the contents of a June issue we have:

- Ongoing comic book adaptation of Ben-Hur

- How to prevent forest fires and how to apply for a career in forestry

- A short story on a Gypsy boy winning the Natural History Prize

- The life of the current Prince of Wales

- An interview with a Chicago police officer on what crime fighting was like in the 1930s

- Story of the ship Emile St. Pierre in the American Civil War

- How the Magna Carta came to be

- Regular series of identification of coins, planes, stamps and trains

- Rob Riley comic: Adventures and daily life of English school boys

- Laugh with Fiddy: Short uncaptioned humour comics

- Wildcat Wayne: Action adventures of a troubleshooter for an oil company

- Trigan Empire: Tales from the history of an interstellar empire, centering around its ruling dynasty

- Dan Dakota – Lone Gun: Western comic

- Origin and meaning of the saying The Widow’s Mite

- Diary entries from James Woodforde in 1786

- The history of RADAR in British aviation

- Ongoing prose serialization of The Mark of the Pentagram, a tale of slavery in the 18th century

- How tea came to be imported to Britain

- Marsh land reclamation efforts on river estuaries

- How William and Dorothy Wordsworth influenced each other’s work

- Picture series on how heavy loads have been transported over the centuries

- Feature on the novel Ring of Bright Water by Gavin Maxwell

- About the game Takraw

- Picture series on Iceland.

As such, it is much easier for a kid to justify dropping their pocket money on this each week when they can also show their parents a page on the lifecycle of a butterfly and give them a series of facts from the life of Jane Austen between reading about spaceflight and the adventures of cowboys.

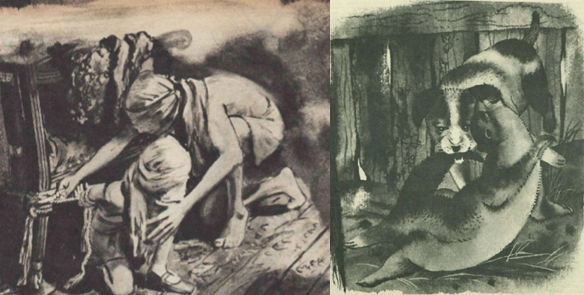

Example illustations for I Am David (left) and Tarka the Otter (Right) (uncredited)

However, outside of the comic strips Space Cadet and Trigan Empire, SF content is rare inside. Keeping to its educational mode, it tends towards historical fiction or uncovering the natural world. With serials tending to be works like The Silver Sword, Tarka The Otter or I Am David.

In fact, I cannot recall any prose serials that have been science fiction, before now. As such, with adult responsibilities getting the better of me, I hadn’t paid too much attention to these pieces. It was only when flicking back through them recently that I perked up at the name Peter Dickinson.

Last year he published The Weathermonger, a book that was much enjoyed by the folks here. This was not only by the same author but Heartsease also takes places in England under The Changes. It was serialised in 10 parts (from 8th March to 10th May 1969).

This is set in an earlier time in the history of this world. Whilst Weathermonger is set when The Changes are a well-established way of life, this is in the earlier stages of these events. As we are told at the beginning:

This is a story about an England where everyone thinks machines are wicked. The time is now, or soon; but you have to imagine that five years before the story starts, because of a strange enchantment, people suddenly turned against tractors and buses and central heating and nuclear reactors and electric razors. Anybody who tried to use a machine was called a witch or stoned or drowned.

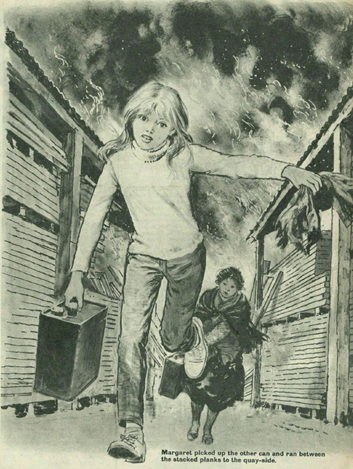

Illustrator uncredited

In the Cotswolds, Margaret and her cousin Jonathan live with her Aunt Alice and Uncle Peter, plus two servants Lucy and Tim, the latter of which is unable to speak. Near their village, an outsider is found using a radio and is sentenced to be stoned as a witch.

The horror of witnessing the stoning seems to break Jonathan out of the hatred the adults have, so he works with Margaret, Lucy and Tim to free the man condemned for witchcraft. Hiding him he reveals his name is Otto, he is an American sent to investigate the situation in Britain when he was caught. The children agree to get him back to his ship.

However, the local Sexton, Davey Gordon, is still on the hunt for Otto. What’s more he is suspicious of Lucy and Tim, given the latter’s disability. They all form a plan to help him escape using an old tugboat called Heartsease.

Illustrator uncredited

I can understand why this would appeal to the editors of Look and Learn. With the removal of technology, it resembles historical fiction and does not have the magical elements of The Weathermonger. In addition, it contains information on how locks work, so it can be marketed as educational.

It is a much smaller tale than The Weathermonger, just about young people trying to do the right thing as they get caught up in horrific events. But, for that, it becomes a bit of a deeper tale. As well as having plenty of adventure, it looks at how we treat others and posits some darker reasons why things may be happening than is revealed in the prior novel:

“…they’ve done so many awful things they’ve got to believe they were right. The more they hurt and kill, they more they’ve been proving to themselves they’ve been doing God’s will all along.”

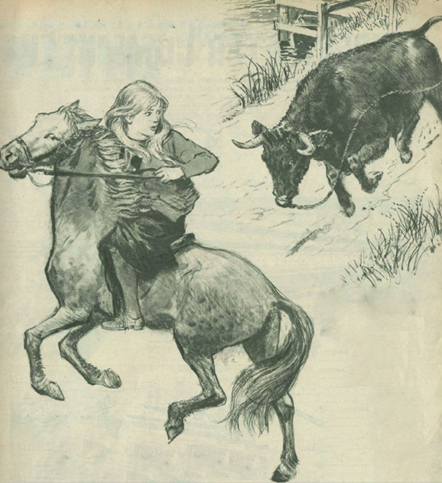

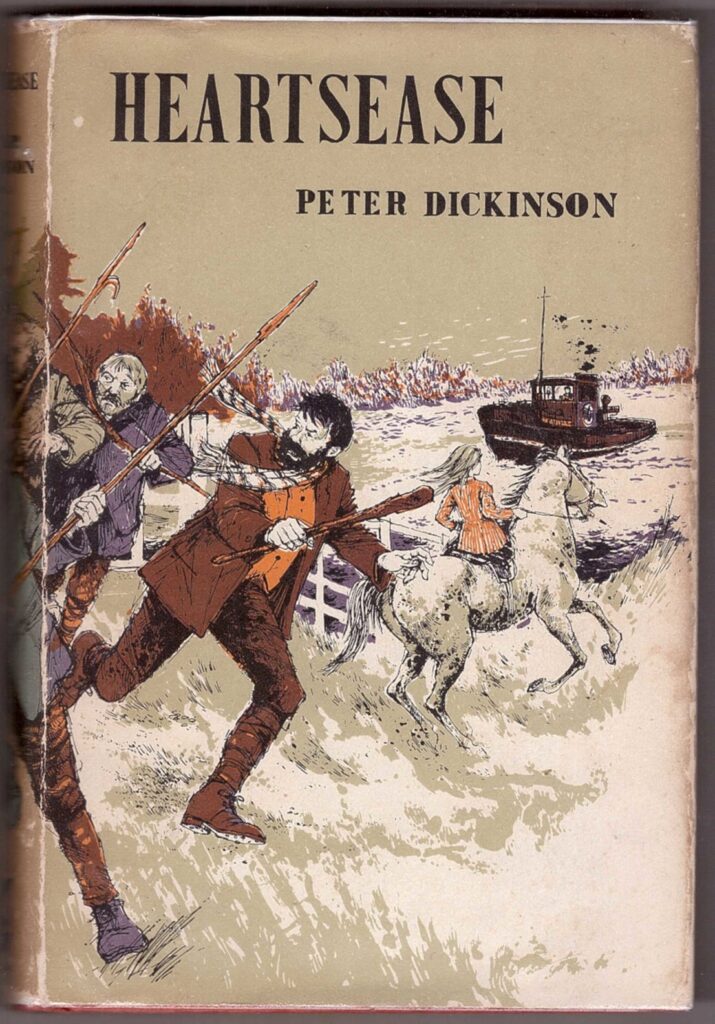

Gollancz book edition. Unknown illustrator

Based on some fag-packet-maths I estimate the word count here is somewhere between a third to a half of what is in the book version, so there is likely more story to be told.

But for this serialized form, I will give it Four Stars.

by Victoria Silverwolf

Bigger and Better?

Two novels that are expanded versions of earlier, shorter works fell into my hands recently. Will this added verbiage improve them? Let's find out.

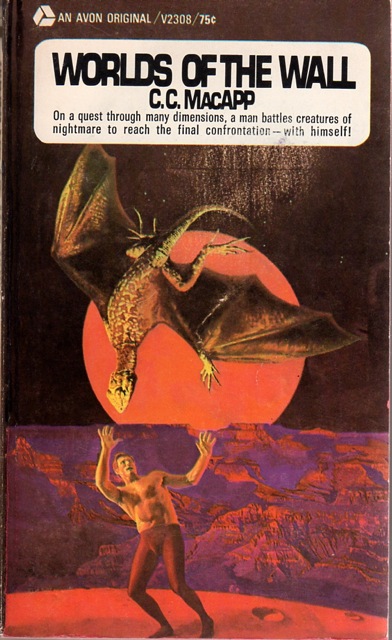

Worlds of the Wall, by C. C. MacAppp

Anonymous cover art. Human and pterodactyl number one.

This book started life as a novelette called Beyond the Ebon Wall in the October 1964 issue of Fantastic. I reviewed it at the time, giving it two stars. That's not a good omen, but let's not give up hope.

Our hero is inside an experimental starship. He winds up near a planet that seems to be missing an entire hemisphere. Forget all this science fiction stuff, because the rest of the book is pure fantasy.

Landing on the weird world, the guy finds out that the place is divided in half by a gigantic wall. He sees two naked men fighting and an elderly fellow with a scarred face. The latter seems very familiar, which is a clue as to the novel's major plot twist.

The protagonist passes through the seemingly solid wall as if it weren't there. He meets a double for the elderly guy and hears a huge magpie recite an enigmatic poem. This begins an odyssey that involves becoming a galley slave, taking part in a hunt for a gigantic beast (which develops a bond with a hero), and battling a pirate captain allied with a sorcerer. It all winds up where it started.

This is the plot of the novelette, so what's new? The middle section of the novel, detailing the hero's adventures as a galley slave, is much longer. There's a vivid scene of the protagonist and his shipmates climbing down a gigantic cliff.

The new version is a slight improvement on the old one. The explanation for what's going on, involving multiple continua and time travel, still doesn't make much sense, but it's a little less incoherent that before.

Two and one-half stars.

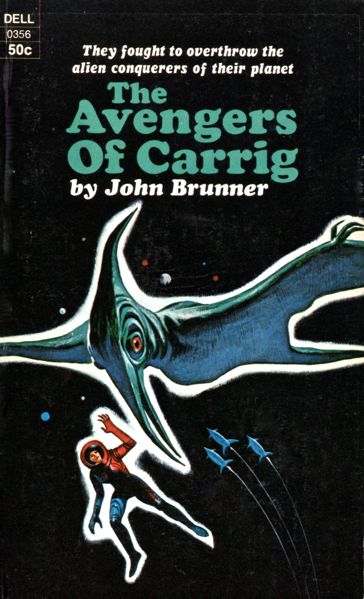

Thbe Avengers of Carrig, by John Brunner

Cover art by Jack Gaughan. Human and pterodactyl number two.

A shorter version of this novel appeared in 1962 as half of an Ace Double, under the title Secret Agent of Terra. It was reviewed by my esteemed colleague Rosemary Benton, who gave the twin volume four stars as a whole.

The setting is a planet settled by human refugees from a nova that wiped out another colony world many centuries ago. The survivors have evolved into a medieval, feudal kind of society. Carrig is the dominant city-state. The place has an ancient ritual of choosing its leaders in an unusual fashion.

Contenders for the title of regent board gliders and try to kill the biggest and strongest specimen of the giant flying beasts that inhabit the planet. (The winner is called a regent because the creature is considered to be the true king.) If nobody slays the animal, which definitely puts up a good fight, the former regent retains the title.

A couple of strangers show up, one of whom easily kills the so-called king with what is obviously highly advanced technology. It's clear to the reader, if not the locals, that they're from another world. Along the way they kill a fellow who discovers their nefarious plan.

The victim was secretly an agent for the folks who keep an eye on refugee planets like this one, being careful to avoid interfering with their natural development, but also making sure other people don't take advantage of them.

When the dead man stops sending messages back to his superiors, they send a fledging agent, along with an older, more experienced one, to the planet to find out what happened. (The young agent is something of a snob and unpopular with the others, so this is one last chance for her to prove herself during what is supposed to be a routine mission.)

They don't know the bad guys are there (they think the deceased agent has gone silent for some other, less sinister reason) so they're taken completely by surprise when an enemy spaceship attacks. The young agent winds up in a frozen wasteland. We don't find out what happened to the older man until later.

As luck would have it, she joins forces with the fellow who was the favorite to become the next regent. Both of them win an unexpected ally in the form of one of the flying creatures, who turns out to be a lot more intelligent than they thought.

Like MacApp's novel, this is strictly an adventure story. The big difference is that Brunner offers a tighter, more unified plot (even if it does depend on some remarkable coincidences.) It's not a complex, ambitious work like Stand on Zanzibar or The Jagged Orbit, but it's highly competent entertainment.

Three and one-half stars.

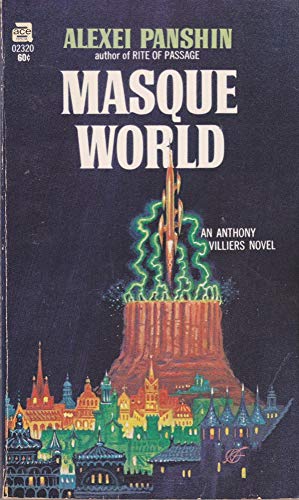

Masque World, by Alexei Panshin

by Jason Sacks

Last year I reviewed the first book in Alexei Panshin's "Anthony Villiers" series, Star Well . I praised the book for its wry, often post-modern take on heroic fiction, digging Panshin's frequent absurd sidebars and silly takes on events.

Now the third book of the Villiers series is out, and Masque World offers much the same as his earlier book: it's absurd and wise, clever and sometimes frustrating, and a pretty delightful "shaggy dog" story.

cover by Kelly Freas

This time Villiers and his pal, the Trog named Torve (a deliberately odd alien creature who is thoroughly uncanny for most people) have found their way to Delbalso, "a semi-autonomic dependency of the Nashuite Empire," as the introductory text informs us. When there, the duo gets deeply involved in all kinds of affairs in the kingdom, many centered around Villiers's uncle Lord Semichastny who is obsessed and addicted to melons (did you know there are over 100 different types of melons? Semichastny can tell you all about that topic, and many more, as if he's some sort of savant or young child in adult form).

Cultures are games played to common rules — for convenience. The High Culture, while not superior to very much, is a fair-to-middling game, and that is all.

There's also an angry robot bulter who seems to resent his subservient role and who tells spooky stories to the other mechanical creatures in Semichastny's castle, and there's a Semichastny friend who gets transformed when he puts on a costume, and there's a cult who seem incredibly happy – perhaps too happy for their own good.

Monism promises only one thing, to make you very very happy. There is a catch, of course. To be happy as a Monist, you must accept Monist definitions of happiness. If you can — you have a blissful life ahead of you. Congratulations.

A lot of this story, therefore, centers around the idea of identity, how to shed identity and how to transform identity; how identity conforms to crowds and how identity stands alone. This all does a wonderful job of showcasing Panshin's elusive commentary on the human condition. As becomes clear by the end, it's the humor and commentary which matter here, not the story.

Do places dream of people until they return?

For the longest time I kind of fought this book, trying hard to make sense of the twists and turns of its plot. Until, that is, I realized that plot is meant to be arbitrary and somewhat confusing. Its twists and turns reflect the mindset of Mr. Panshin, and that and his wordplay – highlighted here as excerpts – are the key things he wants to share with readers.

Holidays are no pleasure for anyone but children, and they are a pleasure only for children only because they seem new. Holidays are no pleasure to those who schedule them. Holidays are for people who need to be formally reminded to have a good time and believe it is safer to warm up an old successful party than to chance the untried.

Masque World is very loose and fun, a bit arbitrary and silly, and I enjoyed it alright. The book feels a bit indulgent at times, and Panshin's having a bit of a goof, but it's well worth 60¢ and 3 hours of your time.

The ending promises a fourth book in the series, to be called The Universal Pantograph. I do hope we get to spend more time in this wildly discursve world of the one and only Anthony Villiers.

3 stars

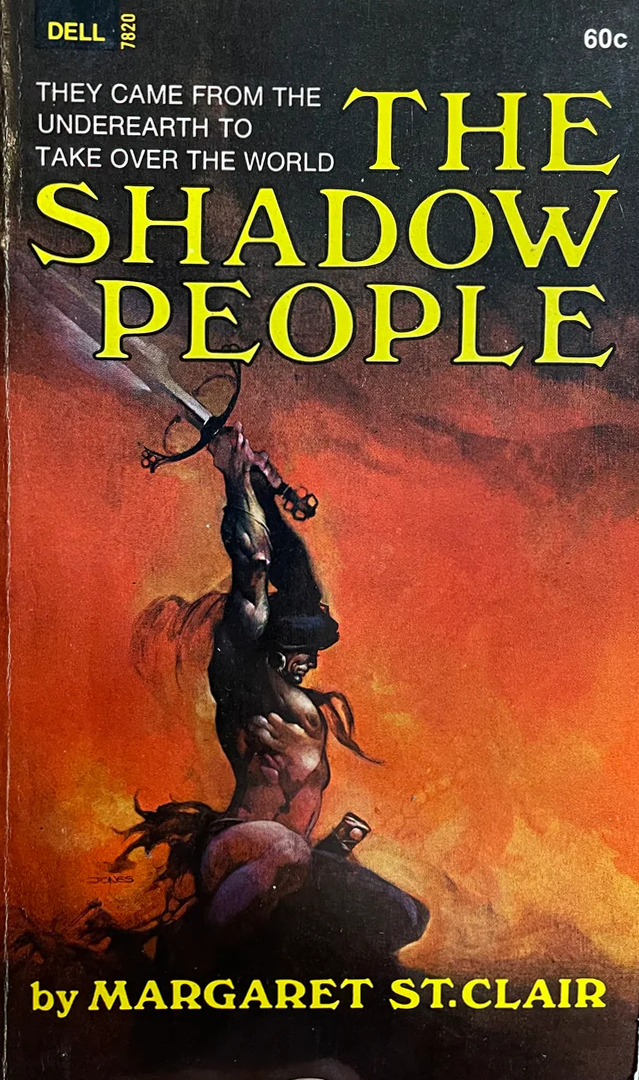

The Shadow People, by Margaret St. Clair

by Tonya R. Moore

I had never encountered any works of fiction written by Margaret St. Clair before reading The Shadow People. The story’s premise is wonderfully dark and imaginative but the reader’s sense of wonder is drowned out by the book’s glaring faults.

cover by Jeff Jones

Aldridge, our hero, descends into a strange and alien underworld in search of his girlfriend who has gone missing. He finds her while navigating this strange dimension, but something about her has been irrevocably altered. Even so, Aldridge seeks a way back to the human world for himself and for the love of this life. When he/they finally returns to the surface, he finds that during his absence, human civilization was twisted into a dark, futuristic dystopia where people are now heavily policed and managed like cattle.

The fact that a female author would center a male character in her work feels like some kind of betrayal. I understand that science fiction tends to be a male-dominated genre, where only men can be the heroes and only men are expected to save the day. But Carol is the one who disappears into the fae realm first. Why does she need to sit on her laurels and wait for The Man to come and save her?

Furthermore, Carol is transformed into a mindless shell of a human, devoid of any ability to express any will of her own or even think for herself. Ultimately, The Man must dictate the woman’s fate. So much for the Women’s Rights Movement. There is a part of me that expects female authors to push back against such demeaning notions and St. Clair, in very bad taste, seems to capitulate to this male chauvinist ideology. Perhaps it was this bias that made it impossible for me to resonate with this story’s protagonist.

Aldridge is a canned character. He is everything a heroic male protagonist “ought” to be and possesses very little depth or complexity in personality. He responds “correctly” to every situation and never seems to doubt or question himself. This leaves a discerning reader with little choice but to question his humanity.

Another possible reason the story rankled was the way elves are portrayed in The Shadow People. St. Clair's version runs counter to the commonly held mental image of elves, portraying them as grotesque and malevolent, instead of beautiful, good-willed, and elegant. St. Clair’s elves are more like the lesser known spriggans of elven lore. This, I agree, is very clever of St. Clair but still, broadly classifying these beings as “elves” felt like needlessly shattering the average reader’s fanciful notions about fae-kind.

There are some disconcerting allusions here to the alienation and institutionalized oppression of the Negro people. As a black woman, I felt that there was a certain lack of sensitivity in drawing these parallels while also side-stepping the cruel reality plaguing modern society.

The imagery in The Shadow People is visceral and draws the reader into every moment. The events of the story are quite dramatic and would make a great film. For some reason, though, none of this resonated with me. I could not fully appreciate or enjoy reading this book nor could I quite rid myself of the vague suspicion that this author had to be a man, a misogynist at that, writing under the guise of a female author.

2.5 stars.

West of Sol

by George Pritchard

Postmarked the Stars

Cover by R. M. Powers

There is a phrase, deja vu, which refers to feeling or seeing something that you have not interacted with before, yet seems intensely familiar. These are now believed to be psychic echoes, but it is a useful term for Andre Norton's latest work, Postmarked the Stars. I was excited to begin this, as the last thing I read of hers was Star Man’s Son, which I enjoyed deeply and still own a copy of.

I want to emphasize that I did not hate this book, nor did I find it incompetent, but reading Postmarked feels like watching a piston engine. Smooth and efficient and automatic, but always quite obviously a machine. This is the fourth entry in the Solar Queen adventures, although no previous books need to be read to understand this one. The previous book in this series came out a decade ago, but I am not particularly familiar with what interest there was, or is.

Dane Thorson, assistant cargo master to the Free Trader ship Solar Queen, discovers that a strange, radioactive box on board is causing the creatures near it to change, becoming larger and more intelligent. Before the crew can figure out what to do with this information, the ship is caught in a tractor beam, and they are dragged to the planet’s surface. Dane, Tau the medical officer, and the psychic cat end up separated into a search party. A group of dead miners are found, an enormous insect monster is battled, before another tractor beam drags them and the planetary ranger onwards towards a secret base in unexplored territory. It all seems to be connected to that strange, radioactive stone!

Is there indeed gold in them thar hills?

One thing I have always enjoyed about Norton's writing, particularly given the genres she works in, is the equal footing she gives to non white characters. Even the names she gives to background characters vary in ways that speak to strength in differences amongst the stars — names from the Indian subcontinent right alongside Welsh, Jewish, and Chinese! For another example, a prospector type is introduced, and it's only mentioned half a chapter later that he is dark-skinned.

This story is a space Western, plain and simple. The recent movie, Moon Zero Two [review coming out October 18] is my immediate point of comparison, but this has been a rich vein in the genre for a long time. The potential for racism in the story is, for better or worse, replaced by that dullest of Westerns, the claim jumper plot, combined with the Pony Express or stagecoach robbery.

Norton has been publishing continuously for almost two decades at this point. Maybe she needs a break, taking a chance to look at the New Wave trends and use them for her own. I know that, given time, she can make them shine the way Star Man’s Son pushed the boundaries of boy’s adventure novels. Norton can do better, and has, but Postmarked the Stars does nothing at all.

Two stars.

![[October 16, 1969] The March Goes On (<i>Heartsease</i>, <i>Masque World</i>, <i>The Shadow People</i>, <i>Avengers of Carrig</i>…and more!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691016covers-672x372.jpg)

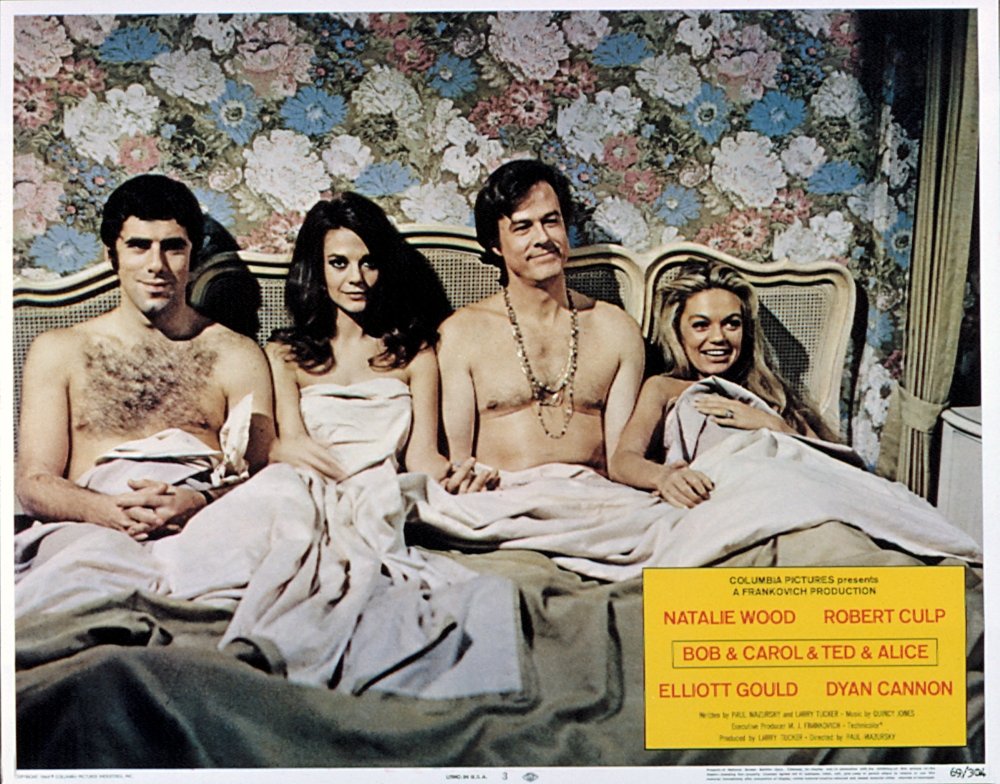

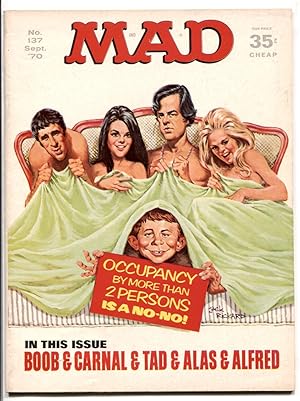

![[October 14, 1969] News Bulletin/No Separate Beds (Review of "Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/bobandcarol-672x372.jpg)

The Alvin

The Alvin

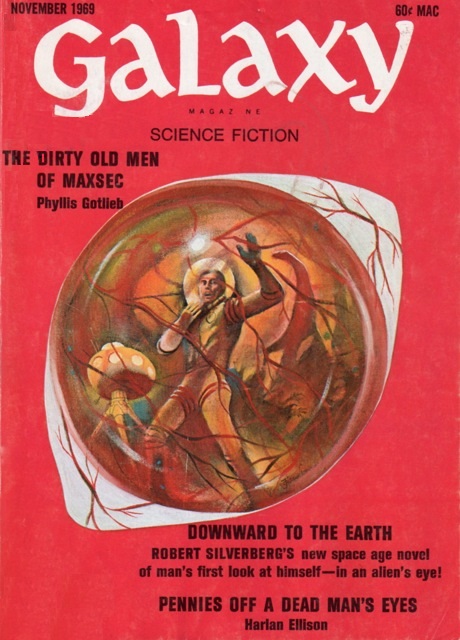

![[October 12, 1969] My country, right or… (November 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691010cover-460x372.jpg)

![[October 10, 1969] Everybody's Talkin' At Me: <i>Midnight Cowboy</i> and Urban Tragedy](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691010midnightcowboyposter-1-672x372.jpeg)

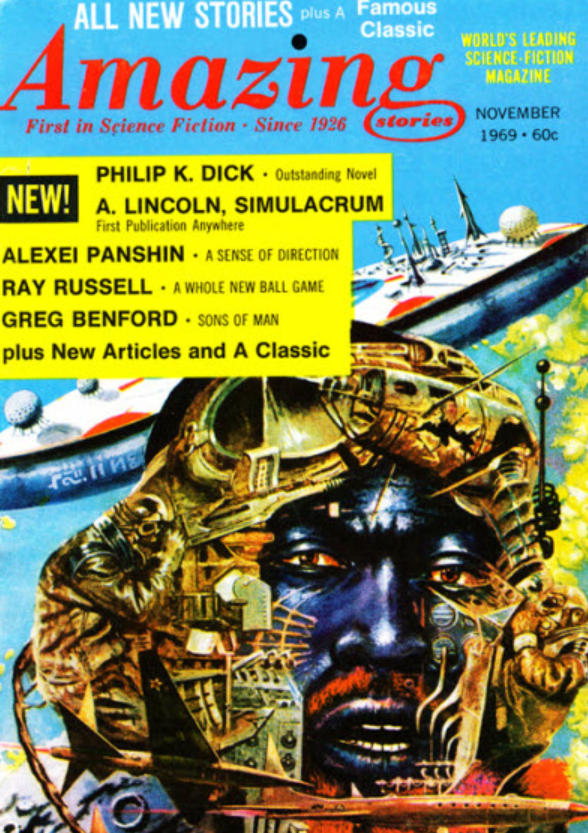

![[October 8, 1969] Suddenly . . . (November 1969 <i>Amazing)</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/amz-1169-cover-672x372.png)

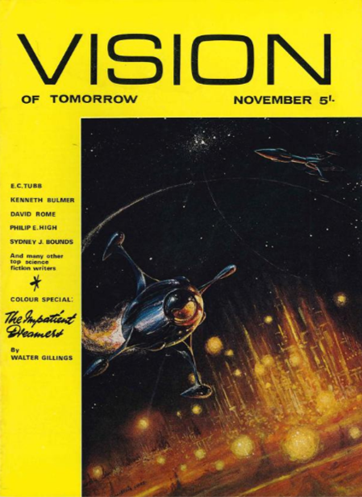

![[October 6, 1969] The Rule of a Mediocracy (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #3</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Vision-2-362x372.png)

![[October 2, 1969] Darkness, Darkness (November 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IF-1969-11-Cover-503x372.jpg)

King Idris from a couple of years ago.

King Idris from a couple of years ago. Libya’s new Prime Minister, Soliman Al Maghreby.

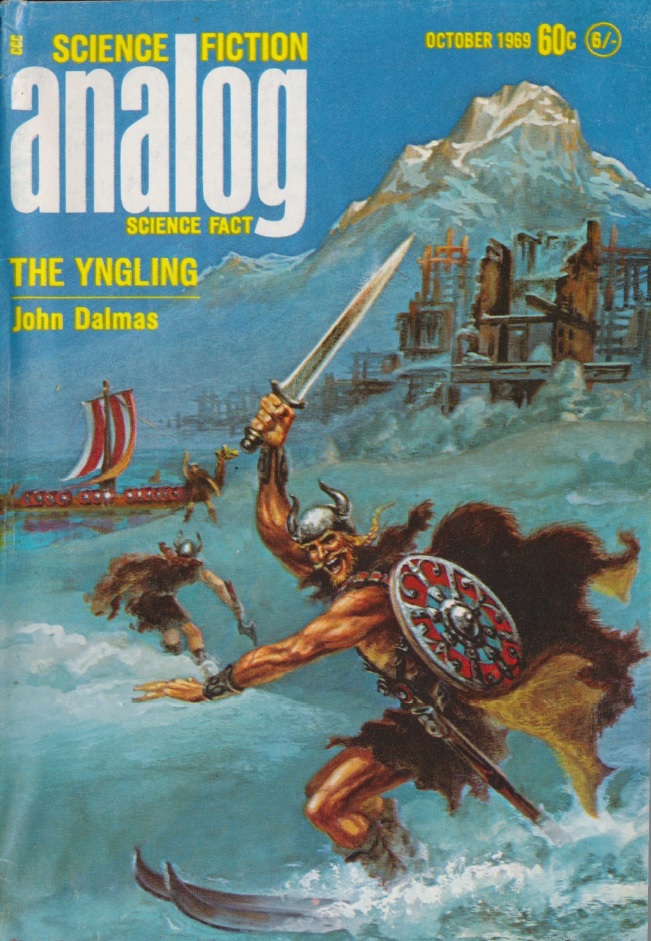

Libya’s new Prime Minister, Soliman Al Maghreby. This month’s cover depicts nothing in particular. Art by Gaughan

This month’s cover depicts nothing in particular. Art by Gaughan![[Sep. 30, 1969] Decisions, decisions (October 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690930cover-651x372.jpg)

.jpg)

![[September 24, 1969] Murder, Madness, and Middle Age (<i>What Ever Happened To Aunt Alice?</i> And Its Predecessors)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690924aliceposter-600x372.jpg)

![[September 22, 1969] Unsmoothed curves (October 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690922fsfcover-658x372.jpg)