by Gideon Marcus

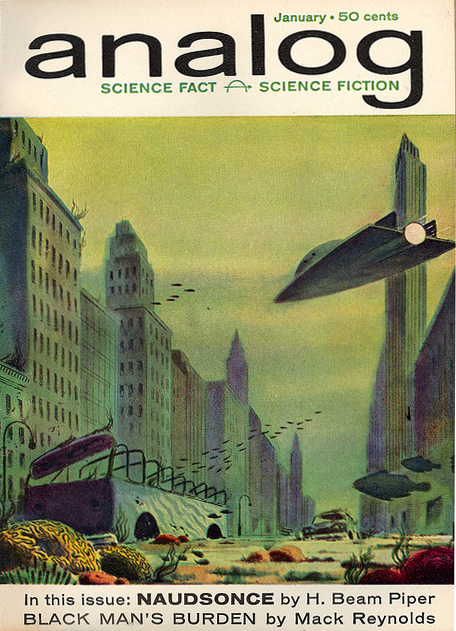

Our effort at the Journey to curate every scrap of science fiction as it is released, in print and on film, leaves us little time for rest. Even in the normally sleepy month of December (unless you're battling Christmas shopping crowds, of course), this column's staff is hard at work, either consuming or writing about said consumption.

I try to write my annual Galactic Stars article as close to the end of the year as possible. Otherwise, I might miss a great story or movie that had the misfortune to come out in December.

Fortunately for that report, but unfortunately for us, neither of the films in the double feature we watched last weekend had any chance of winning a Galactic Star.

Both of them were low budget American International Pictures films. This is the studio best known for making B-movie schlock for the smaller Drive-Ins. However, they also brought us the surprisingly good Master of the World as well as the atmospheric Corman/Poe movies. So I'm not inclined to just write them off. This time, however, we should have.

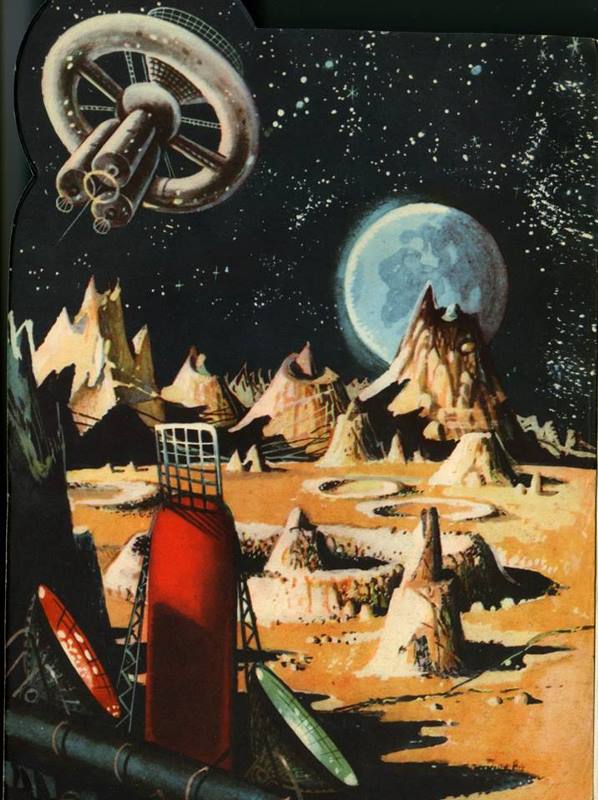

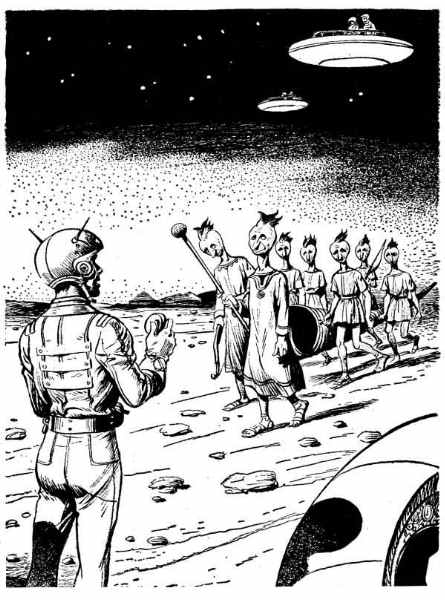

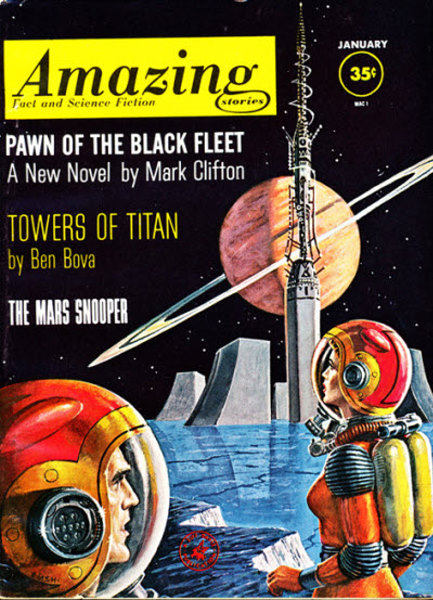

The Phantom Planet is a typical first-slot filler movie. Spaceships launched from the moon keep getting intercepted by a rogue asteroid. Only one crewmember of the third flight survives, a beefcake of a man who shrinks to just six inches tall when exposed to the asteroid's atmosphere. What's stunning is not the lack of science in this movie, but the assiduous determination to avoid any scientific accuracy in this movie. However, I the sets are surprisingly nice…and familiar. They look an awful lot like the sets from the short TV series Men in Space.

"Remember when we flew these last year?"

The people of the asteroid (humans, natch) are a paradox of ultra-advanced technology and primitiveness. They have powerful gravitational devices, operated similarly to the theremin, but they grow food out of rock and spin their own clothes. There is some typical jive about the softness of civilization and the conscious choice to live the harder, but more pure life.

"Decisions…decisions…"

Beefcake pilot must choose between the two women who asteroid chief throws at him. The younger, dramatic-looking one is mute, and therefore more readily impressed with a projected personality. The older one is coveted by the chief's top adviser, and some drama results from that. All squabbles are put aside when enemy aliens appear to blast the asteroid with fire. Beefcake and Jilted Lover work together to defeat them with theremins. One of the lumpy aliens, a prisoner at the movie's start, takes the mute girl captive. She is rescued, and happily for her, the ordeal gives her back her voice. Sometimes it's that easy folks.

"You asked to be woken up at 6…"

Jilted Lover wins the love of Older Beauty. Beefcake takes a gulp of oxygen and returns to normal size. He returns to the moon with nothing but a pebble to remember the formerly mute girl with whom he shared the love of a lifetime in the course of 25 silent minutes.

Not quite one star, I suppose, but not much above it. Call it 1.5.

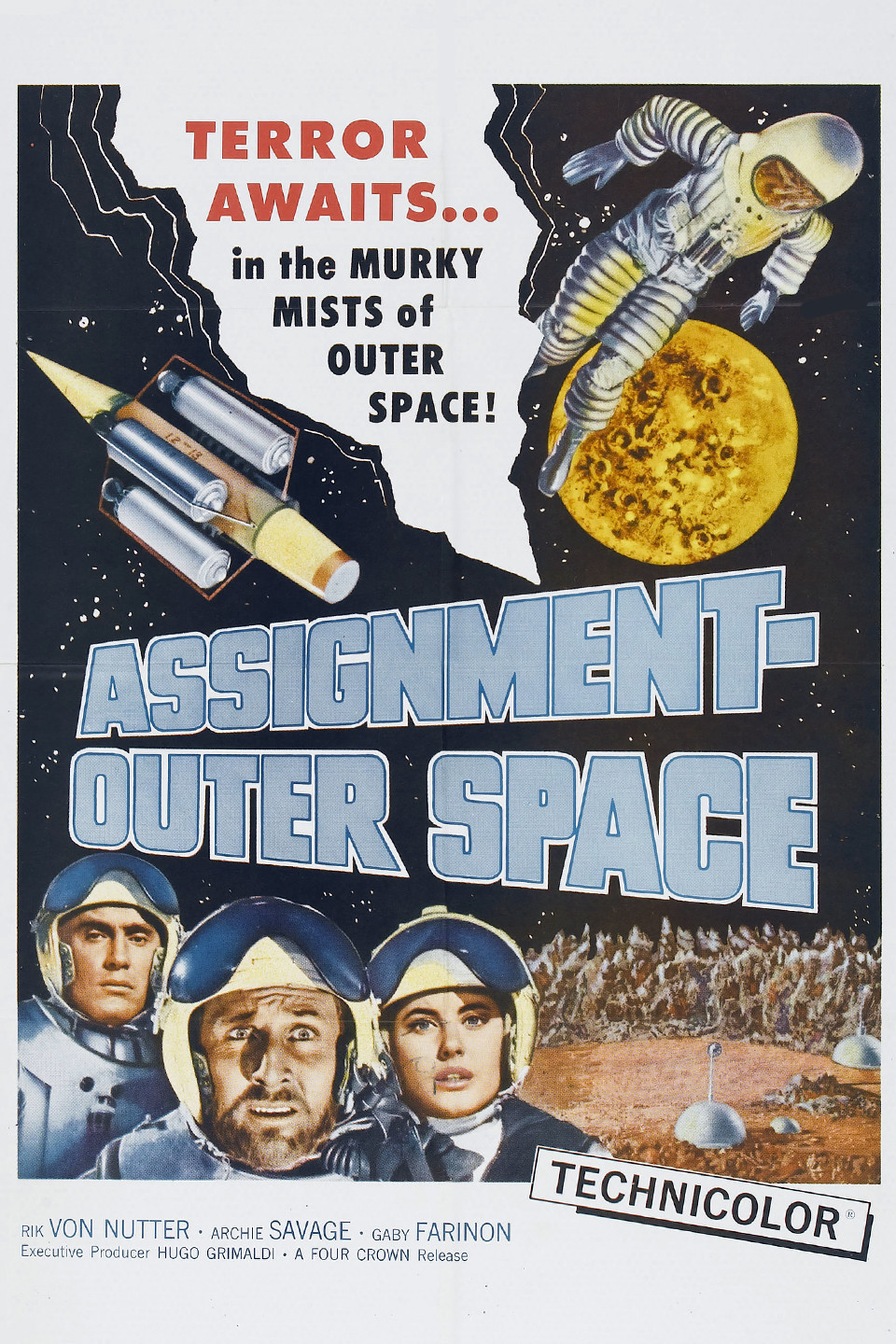

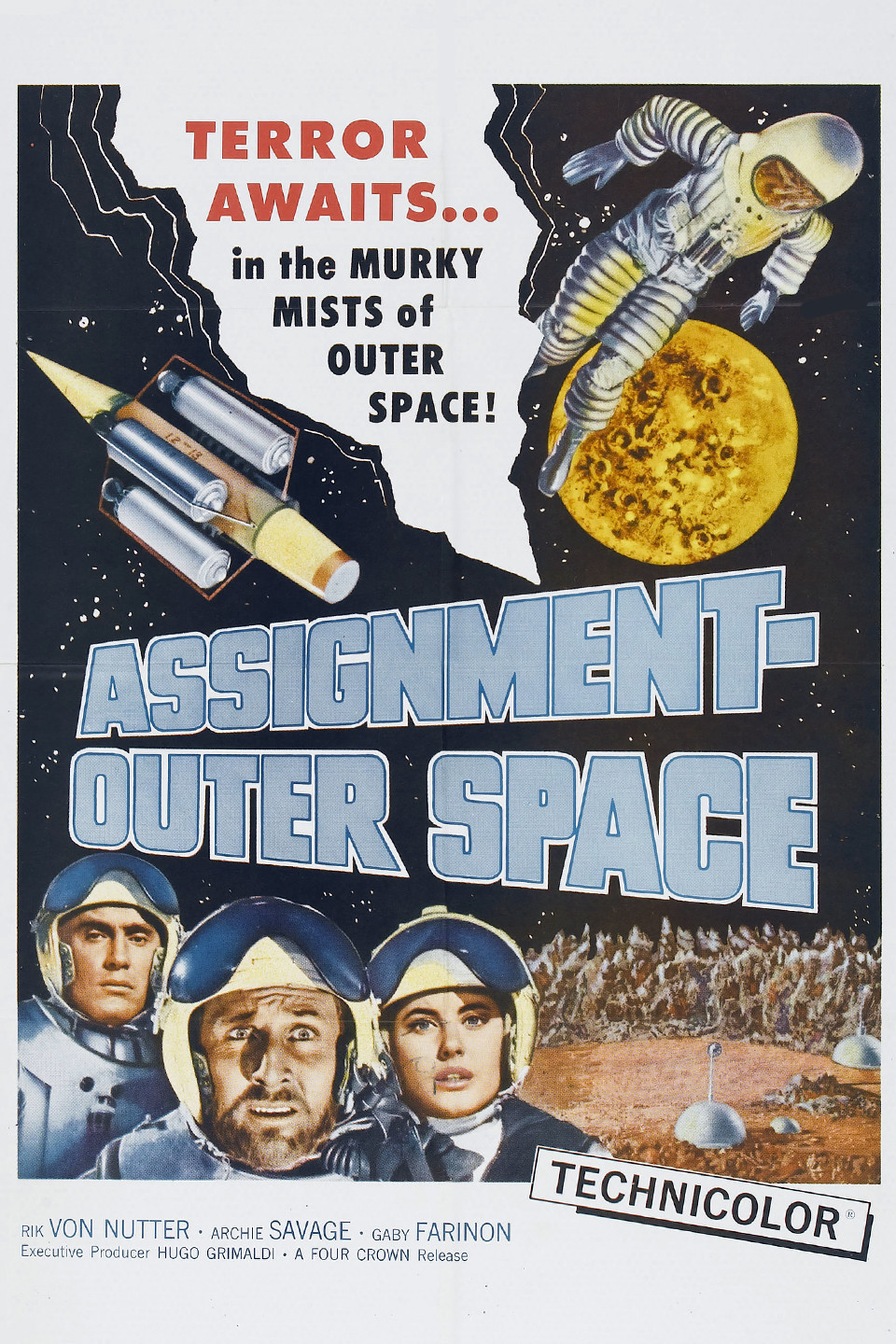

Assignment: Outer Space, the "A" feature, is even worse. An Italian production, it promised to be the superior of the productions, featuring full color, a wider aspect ratio, and a diverse cast. Sadly, Assignment, filmed in Italy and dubbed with signal ineptitude, is a hot mess. The set-up is fine, with an Earth reporter assigned to a space naval vessel to record a routine scientific investigation. There's some refreshing nods to weightlessness and some not terrible in-space shots. The laughable model work is somewhat offset by the serviceable sets. Yet, between the arbitrary plot (an Earth ship's "photonic drive" has gone haywire and will destroy the Earth!!!) the fuzzy grasp of distance (Let's go to Mars! Now let's go to Venus!) and the indescribably poor acting, this film is a dud. And, of course, there is the perfunctory and accelerated romance between our reporter, Ray, and the navy ship's navigator, Lucy. It is as engaging as it is nuanced.

"These plants convert hydrogen into oxygen." "I love you."

Another 1.5 star film (the half-star given for the mildly interesting engineer character, who is both Afro-American and the most competent of the ship's crew).

Of course, as usual, the Junior Traveler came along for the ride. As might be expected of someone with such maturity, culture, and discernment for her age, her views mirror mine…

by Lorelei Marcus

Today me and my dad decided to hit the theater and see what magical experience it would give us this time. We got a double showing, featuring The Phantom Planet and Assignment Outer Space. I will start with the former movie, to keep things in order. So without further ado, the review:

I think Phantom had to be one of the most low budget, poorly written, B movies we've seen so far. However that does not mean it wasn't enjoyable. In fact it was quite humorous, after we decided to add our own little ongoing commentary. It's more a movie to be made fun of rather than watched as a respectable feature. I don't think it's possible to watch it seriously all the way through.

What really intrigued me, is that it was made by the same studio who made Master of the Sky and the infamous Konga! This baffles me, because as you might know, these movies have a drastic difference in quality. In a way that's really an understatement considering Konga was literally the worst movie we've ever seen. I suppose it isn't that surprising for the studio to make The Phantom Planet though. It's about the quality you would expect from a B movie studio.

"I thought cotton shrunk in the dryer…"

In terms of the story, there wasn't one. Things happened, of course, but there was no ongoing plot, just a bunch of random events being thrown in your face, at random! The effects were cool at times, though mostly they just made me laugh. For example, the rubber alien suits on flaming ships, in space. The science of the movie could not be less accurate. I found myself constantly muttering to myself, “That's not how it works!” throughout the movie. Still, that did also give more fuel to make fun of the movie and get any scraps of humor we could out of the mess.

"Theremins…in…space!

I'm going to give this movie 2 stars. Despite being absolutely terrible in every way, the experience around it that I had with my dad was quite enjoyable. I imagine someone going alone would give this movie a lower score than mine, but my experience is going to affect my score – I imagine if I'd gone alone it would probably be a 1 out of 5 stars instead. At least I had fun!

Unfortunately I can't say the same for Assignment Outer Space. We came back from the concession stand with high hopes, after the not-very-good experience we'd just had. Sadly, our hopes were soon crushed into a billion, tiny, disappointed pieces. The worst part is this thing tried to disguise itself as a movie, making the realization that it wasn't even harsher.

We start off on a space ship where the main characters are waking up from hyperspace. We know this, thanks to the constant expositional narration that describes everything that's currently going on in every scene. Despite that, we still managed to be confused about what was actually happening nearly the entire movie, which tells you something.

"I dreamed I was in a lousy movie!" "It's no dream, my son."

Anyway, we are soon introduced to the main character of the film, Ray, who is actually a reporter, and the narration is the article he writes after the movie. This was a terrible, and I repeat, terrible choice on the script-writer's part. Not just because it's completely boring and unnecessary, but it ruins the entire climax of the movie!

For you to understand, I will need to tell you the movie's plot. Unfortunately this movie does not have one, just a series of events with no context or build up whatsoever. The main conflict of the film, which literally appeared out of nowhere, was an indestructible man-made weapon, intent on destroying Earth. The main crew's job is to find a way to stop it, and that's the entire second half of the movie! However we know how it ends from the beginning, we know they save Earth and the main character survives because we know he writes an article that he will share with the world! Plus, its not like the narration was even needed in the first place!

Ray saves the day. Surprise, surprise.

As you can probably tell, that frustrated me a lot, probably because it felt like the entire movie was a pointless waste of time and I wasn't going to get anything new out of watching it. I almost walked out of the theater at one point, especially when they killed the one character I was at all fond of (the engineer sacrifices himself to find the photonic barrier's weakness). But no, I stayed.

"Mustn't… show… emotion…"

I could go on and on about all the flaws in the pacing and acting and dubbing sync etc., but I already pretty much did that for the other movie. In comparison to Assignment Outer Space, The Phantom Planet actually looks like a decent movie (despite being in black and white). So of course, Assignment Outer Space is going to get a lower score of 0.5 stars. I think this is the lowest score I've given a movie so far, and this one deserves it. Konga was incredibly bad, but it had more redeeming qualities than this pile of garbage. I think the only two things I liked about this movie was the style of one of the character's hair, and a shot where the main character turns towards the camera ridiculously slowly for no reason. That's it!

Get used to this shot. You'll see it a lot.

With a steep ratio of bad to good Science Fiction movies this year, I'm really hoping we'll get some better quality stuff in 1962. I wish I were a Time Traveler so I could just go and see, but that would spoil the fun. I hope you all have Happy Holidays, and do me a favor: never watch Assignment Outer Space. Thank you.

This is the Young Traveler, signing off.