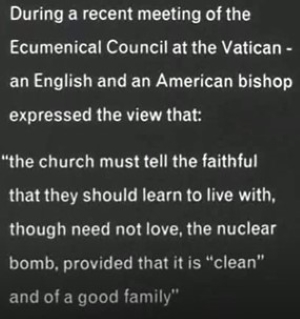

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

Eye Spies

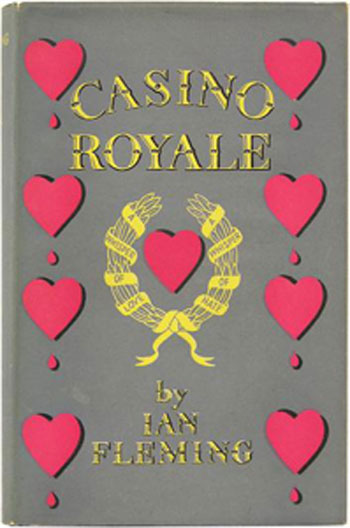

Spies are everywhere these days. James Bond is now just one of many secret agents dominating cinema.

On TV you are spoilt for choice, whether you prefer John Steed, John Drake, Richard Cadell, Napoleon Solo or even Amos Burke.

You can go to any bookshop and pick up the latest thriller from people like John Le Carre, Len Deighton or even by Michael Moorcock (under one of his many aliases).

But also, in real life news. A 92-page document was made public in Vancouver yesterday, detailing the allegation that George Victor Spencer, recently deceased, had been assigned to look into farms near the US border in order to find a suitable property to set up a site that could possibly have been a base for Soviet intelligence operations.

Mr. Spencer had denied these allegations and called for a public enquiry before his death. I imagine the debate about whether he was really a Russian agent or just a falsely accused man will continue for some time.

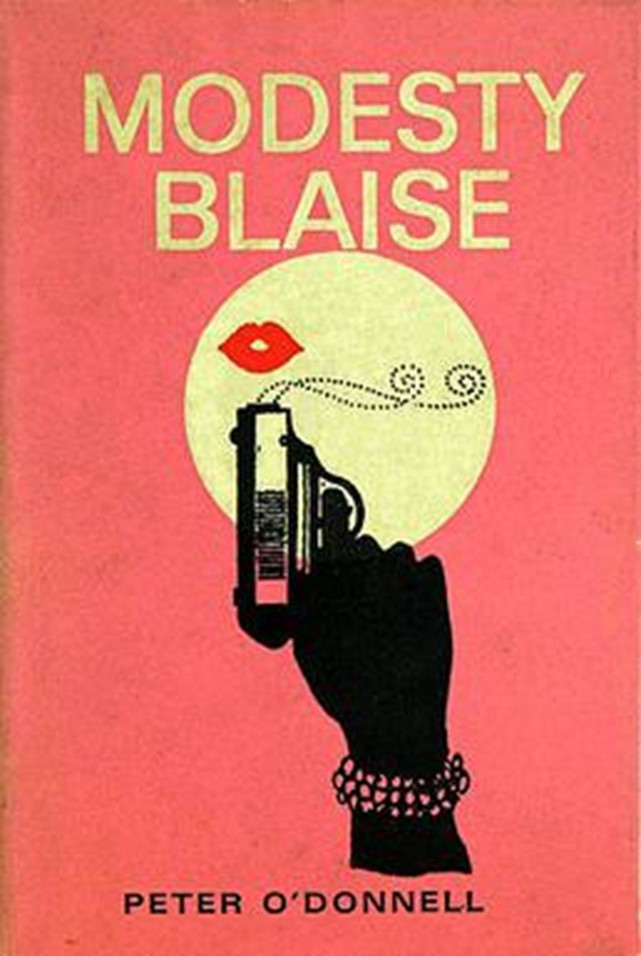

With all this intrigue happening around us, it is perhaps unsurprising that the first ever British comic book adaptation is another spy tale: Peter O’Donnell’s Modesty Blaise.

An Unlucrative Medium

Comic books have not been ones for adaptation in Britain. We did not have the 30s/40s film serials like the United States, so we did not get a Garth Conquers The Universe or The Return of Buck Ryan.

Nor is there a strong enough animation field to produce The Adventures of Dan Dare or The Rupert The Bear Show.

Whilst comics remain popular the idea that we would ever get a Roy of the Rovers or Bash Street Kids film would seem beyond remote. But Modesty Blaise has changed that.

A Pop Culture Icon

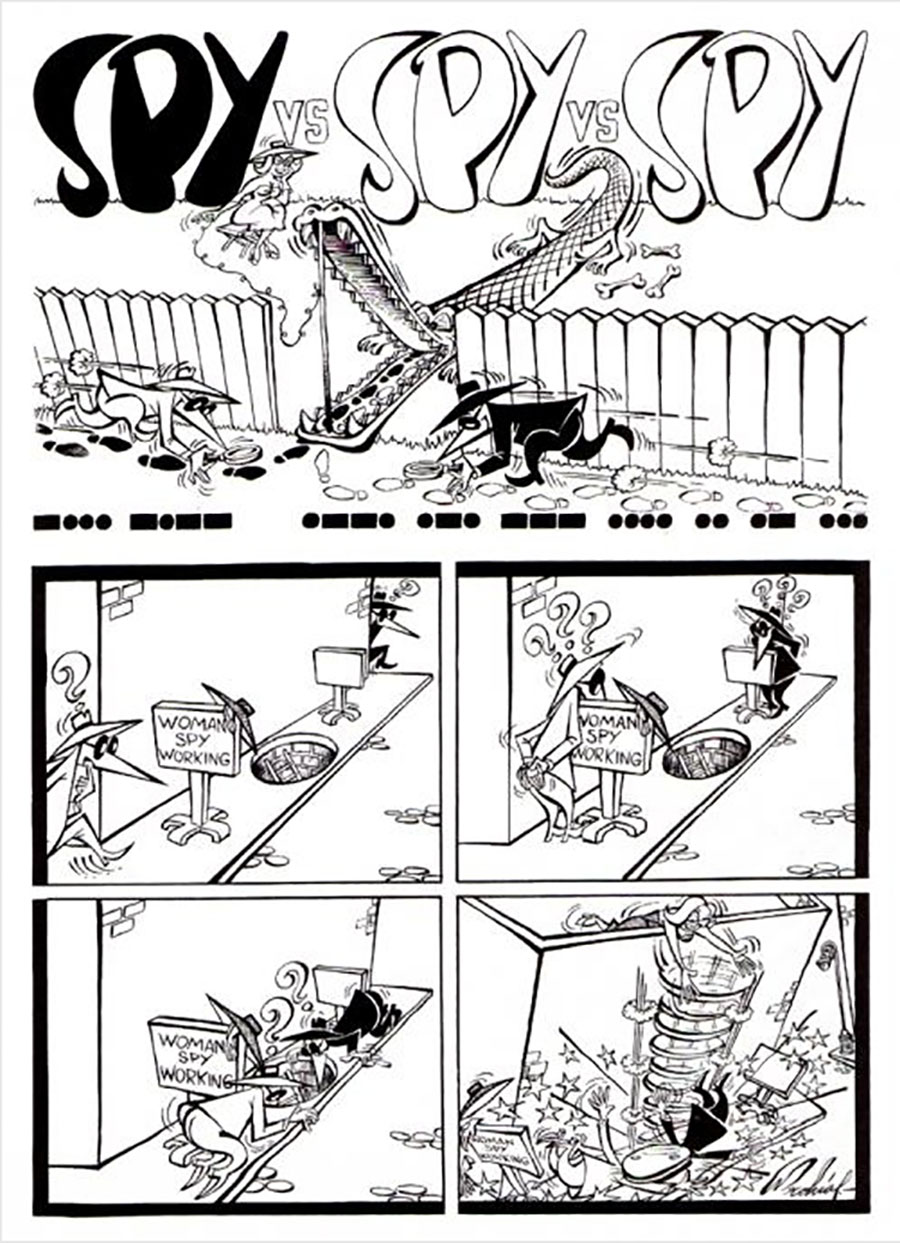

The first strip of Modesty Blaise was only released 3 years ago, but she has already become a massive success. So before talking about the new movie I think it is important to talk about the original strip.

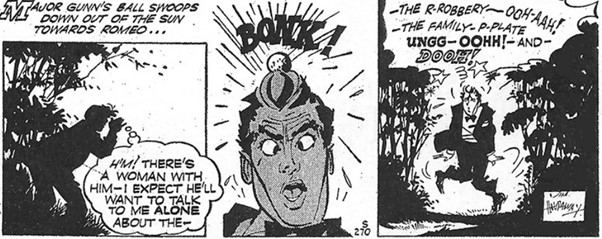

At the same time as working on the beloved adventure strip Garth, the Daily Mirror further employed Peter O'Donnell to takeover Romeo Brown, their comedy comic strip about a bumbling detective, usually involved in silly situations with various young women. The quality of the strip is not that memorable, but it is there he began collaborating with Jim Holdaway.

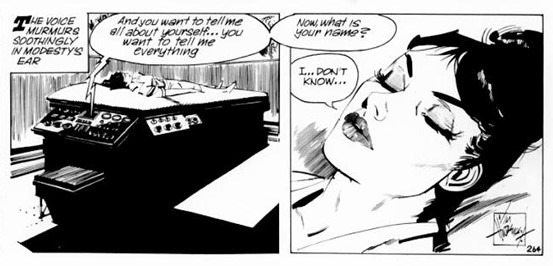

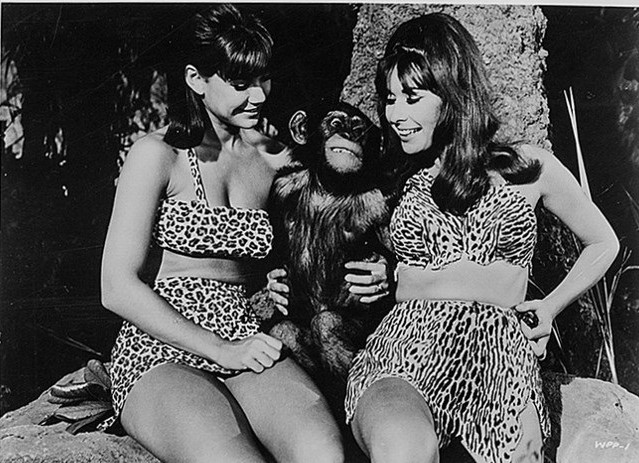

After Romeo Brown finished, Peter O’Donnell decided to create a more serious strip where a woman would be a capable hero rather than simply an object of desire or a damsel for the man to rescue. Apparently inspired by an orphan girl he met when stationed in Persia during the war, he teamed up once again with Holdaway to create Modesty Blaise.

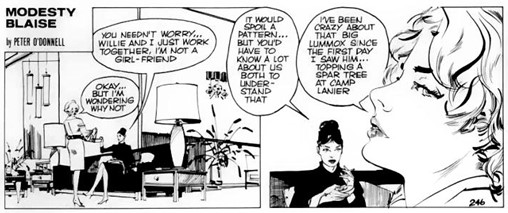

Starting in 1963, Blaise feels like a totally new type of hero. Both Modesty Blaise and Willie Garvin (her loyal sidekick) are both former criminals neither from privileged backgrounds. Modesty grew up in refugee camps in Persia and other Middle Eastern countries, whilst Willie is very much a working-class character. There is also no suggestion that she has any romantic interaction with Willie, instead they are loyal professional colleagues.

It is not just the initial concept that is fresh, the quality of the strip feels ahead of anything else I could easily pick up. O’Donnell’s plots feel fresh and complex, varying significantly from story to story. One week she will be investigating drug running in the Vietnam war, the next dealing with psychic espionage. These are combined with characters that feel deep and real. O’Donnell’s writing and Holdaway’s art also come together to give a really cinematic presentation with a real eye for direction.

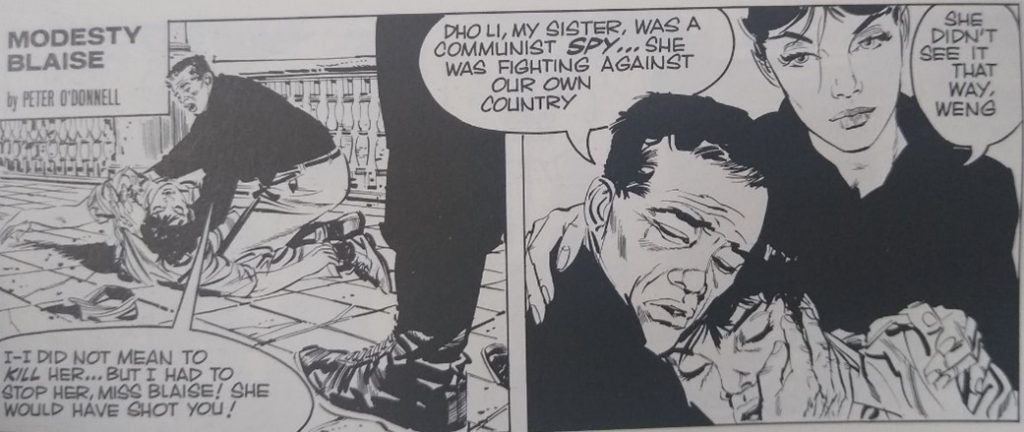

Whilst it can often feel like comic books lag behind literature (most science fiction strips seem to be barely coming to grips with the Golden Age), Modesty Blaise often feels like it is closer to the new wave of British espionage literature. Rather than the old-fashioned heroics of James Bond, Blaise owes something to the George Smiley tales or The IPCRESS File, with a certain level of cynicism about intelligence operations.

The prospects for the film seemed good at first. Peter O’Donell wrote the initial story for the film, although it was changed significantly for the screen (his novelization is based on his script rather than the finished product) with the main writer and director representing a reunion of Joseph Losey and Evan Jones, the team behind the brilliant Hammer Film The Damned.

So, I went in to see it on the first day of release quietly confident…

An Outrageous Mess

…and I am honestly not sure what I got. It is almost like every scene was made by a different director, none of whom talked to each other, and all footage edited together in five minutes at midnight.

It is quite an experience to watch and hard to believe it was ever released. Is the intention meant to be satirical? Artistic? Serious? I cannot see it particularly working with any reading.

If I were to praise anything about it, it is the look. The design work in it is beautiful, taking full advantage of being in colour to showcase bright locations and fashions. But even that gets wearying quickly. I believe Modesty changes outfit in almost every scene, only briefly wearing her iconic comic outfit for the sake of a cheap joke about how to change out of it. At times it feels less like they consider Blaise to be a spy than a model for Marissa Martelli’s designs.

Rather than the serious tone of the newspaper strip, Losey’s film has a large dose of comedy inserted into it. Some is absurdly silly, some is satiric, some is very dark. None of it really landed for me.

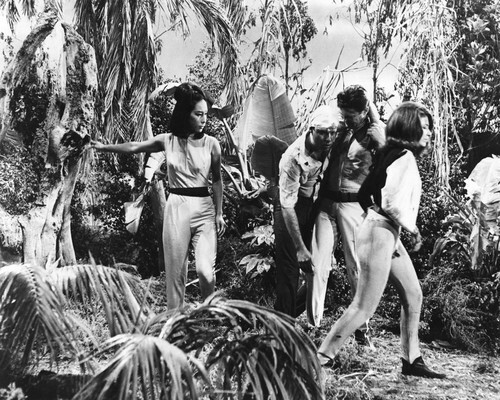

One of the core points of Modesty's character is how skilled a fighter she is. Here the only evidence we see of that is a really poorly choreographed fight scene. For much of the film she is reduced to being a damsel in distress. This is a common problem in British media, I am aware, but that doesn’t make it any less disappointing to see here.

Willie now seems to have transformed into some Alfie-like lothario in a modish bachelor pad rather than an ex-criminal who runs a pub. They also break one of the most interesting elements of the original strip by involving them in a romance. Inexplicably told through musical numbers taking place in between or during action scenes.

Gabriel was previously a Moriarty style figure with an enlarged forehead and walked with a limp. Much like Lex Luthor is to Superman, he seems designed to be the brain to match Modesty and Willie’s brawn. Yet in the film he just appears to be an eccentric, upset about any snag in his plans whilst launching rocket missiles that shoot lasers.

The movie also uses scenes from the original comic but without any real explanation or context. The opening scene appears to be taken from The Gabriel Set-Up but whilst there it is a key plot-point about a device to extract people’s secrets, in the film it appears to be an advanced printer which, in another attempt at humor, is unable to give information she requires and has no relation to the rest of the story.

At the start of this section, I said trying to get a read on what this film is trying to do is tough. As an adaptation it has barely any faithfulness. As a silly comedy the jokes are not directed well enough to land.

If it is a satire I am not sure what of? Imperialism? It is more imperialist than anything. Spy films and TV? The meta-fictional jokes don’t really make sense for that. I never thought a problem with all the espionage thrillers coming out is that they have obvious continuity errors, break out into musical numbers at random or even that they take themselves too seriously. The awful carry-on films do a better job at mockery of popular media than this.

I have heard it is trying to be artful but, honestly, I am not convinced by that either. I am fan of the cut-up approach of Burroughs, Ballard and their ilk but they do this to tell a story as a whole in an interesting way, not to make something non-sensical. Whilst we can debate the true value of Duchamp’s Fountain, I can see the point he was making. The only point here seems to be it is a plainly bad film.

The End…Thankfully

I do not even know if you can truly rank this on a star system. I cannot even be sure what I just watched was actually a film. The only evidence seems to be I paid money to see it in a cinema. The whole thing, whatever it is, is almost worth seeing in order to appreciate how bizarre an experience it is.

However, I come down on the side of staying at home instead. There you can spend your time reading O’Donnell and Holdaway’s wonderful comic strip in comfort. Find out if a newspaper anywhere near you is syndicating it, I hear that it has been picked up all over the world and it is one of the true greats.

Unlike the shambles Losey served up.

One Star

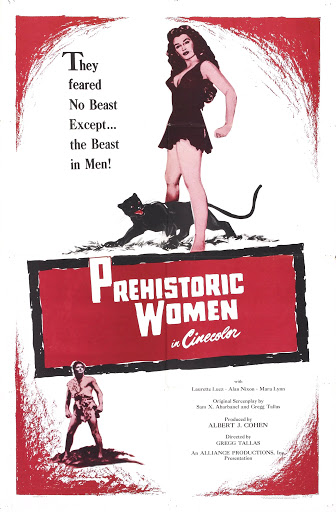

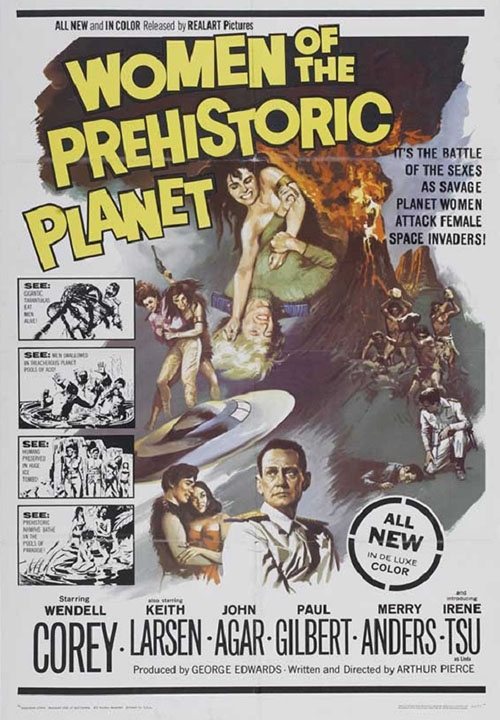

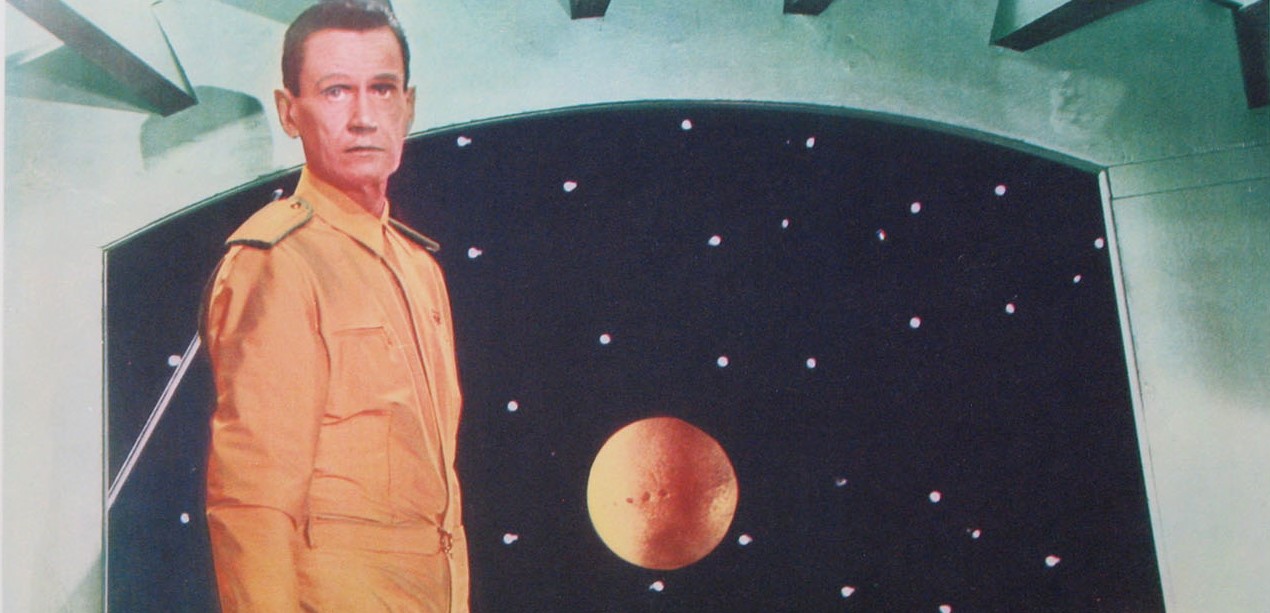

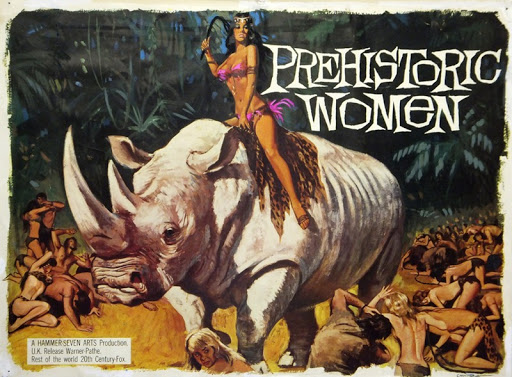

![[April 22, 1966] No Man's Land (<i>Women of the Prehistoric Planet</i> and Further Female Filled Fantasy Films)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/women_of_prehistoric_planet_1966-3.jpg)

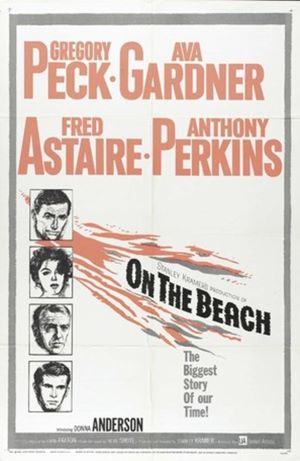

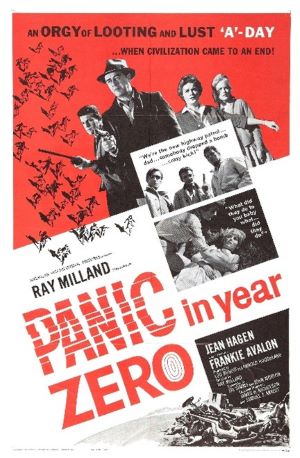

![[April 14, 1966] A New & Clear Bombshell (<i>The War Game</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/War-Game-1a.jpg)

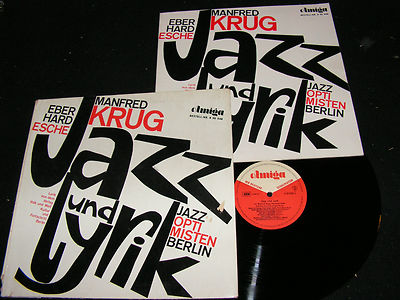

![[April 10, 1966] A Fairy Tale from the East: <i>King Thrushbeard</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/02-junger-Reiter-Manfred-Krug.jpg)

![[March 24, 1966] Dark Comedy and Birthday Wishes (a Tony Randall double feature)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660324b04-672x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1966] Sanguinary Cinematic Surgery (<i>Blood Bath</i> and <i>Queen of Blood</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660304movie-600x372.jpg)

![[February 16, 1966] An import-<i>ant</i> next step in my Sci-fi journey (<i>Them!</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/660216cover-672x372.jpg)

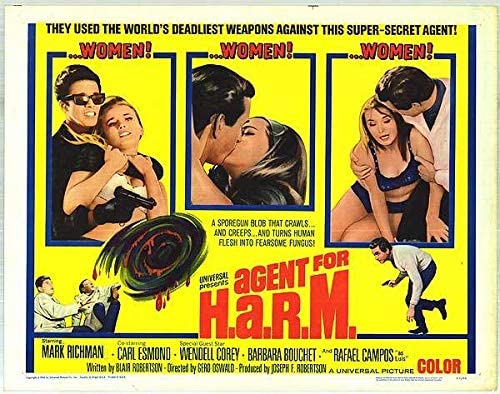

![[January 24, 1966] The Sincerest Form Of Espionage (<i>Agent for H.A.R.M.</i>, <i>Our Man Flint</i>, and Other Bond Imitations)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/51pPnb0TRVL._AC_-500x372.jpg)

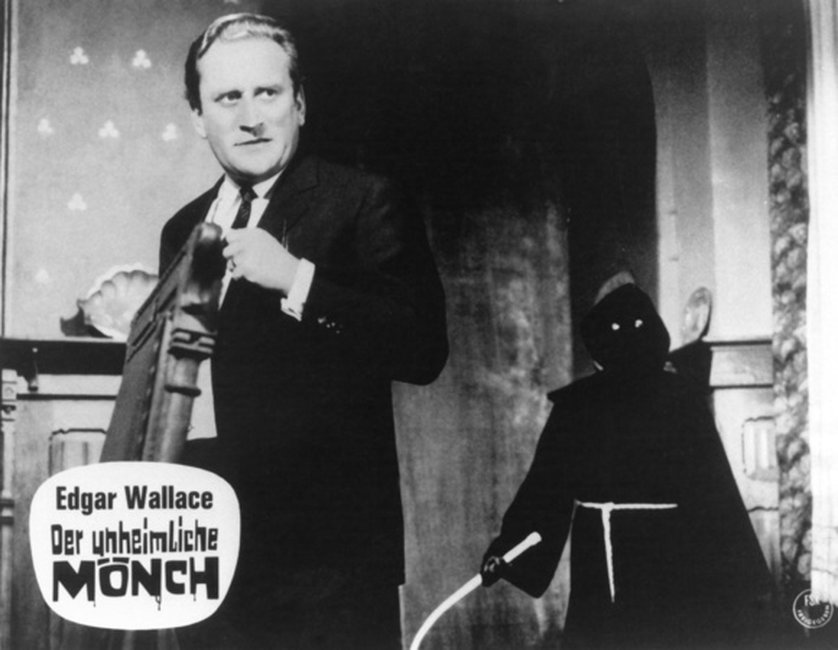

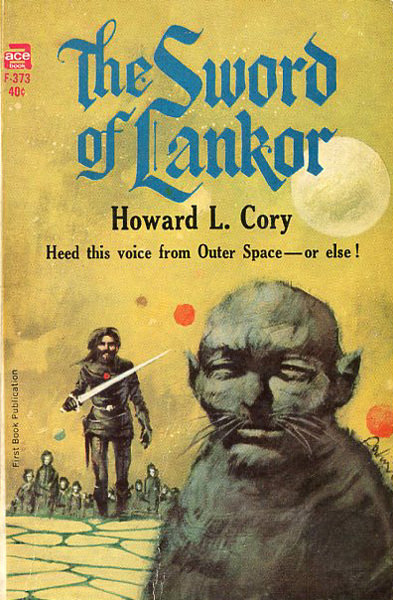

![[January 22, 1966] Monks, Demi-Gods and Cat People: <i>The Sword of Lankor</i> by Howard L. Cory](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/SWRDLNKR1966-393x372.jpg)

![[January 14, 1966] An Excellent Set of Hammers (<i>Dracula Prince of Darkness & Plague of the Zombies</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Hammer-Titles.jpg)