A Trip To Tomorrowland?

by Fiona Moore

People who don’t like trippy, confusing endings for their movies are in for a bad time of it these days. The ending of 2001: A Space Odyssey at least makes more sense than the ending of The Prisoner (the filming of which series overlapped with 2001 at Borehamwood Studios, meaning Alexis Kanner had to share his dressing room with a leopard). The question is, does this make it a better piece of SF visual art?

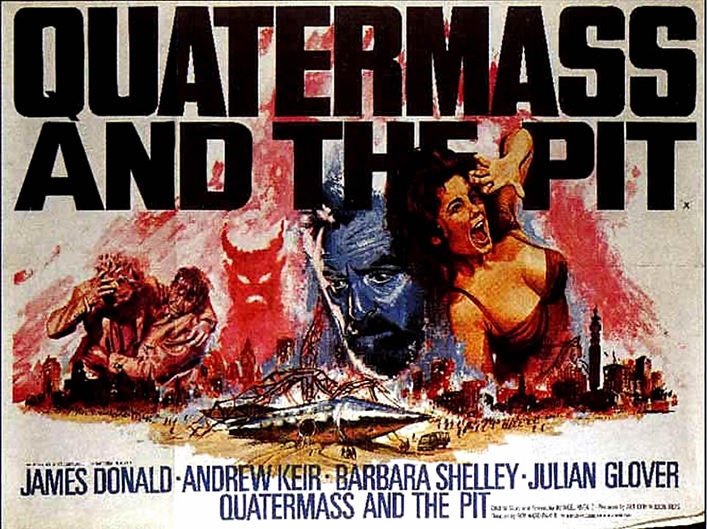

The plot of the movie is fairly thin. Millions of years ago, we see human evolution directed by a strange black monolith, in a premise strikingly similar to that of the recently-released Quatermass and the Pit. We then jump to the near future of 2001, where a similar monolith is discovered on the moon and another near Jupiter. A space mission is dispatched to check the latter out, but things go wrong in a memorable subplot when the sentient ship's computer, HAL 9000, goes mad and kills the astronauts before sole survivor Dave Bowman finally shuts it down. The psychedelic denouement contains the distinct implication that the next stage of human evolution has now been directed by the monoliths, and Bowman has become the first of the new species of elevated humans.

Interspersed with the plot is a lot of depiction of the future thirty-three years from now, with its space stations, ships and moonbases. Despite some very impressive and well-thought-through effects, with actors seeming to stand upside down or move at right angles to each other in zero-G environments, the overall impression was depressingly banal and rather like one of the corporate-sponsored imagined futures in Walt Disney’s Tomorrowland attraction. We may be able to travel to the moon, but we still have Hilton hotels and Pan-Am spacecraft. The characters are also banal, in the case of Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood almost to the point of seeming robotic: HAL is much more of a character than either of the two astronaut dolls.

As an anthropologist, what interested me most was the film’s questions about violence and human nature. The message seemed to be that humans are inherently violent, however evolved we are: the first thing the ape-men at the start of the movie do once they discover tool use is to kill a tapir and then make war on a rival tribe. Bowman’s last significant act as a human is to kill a sentient machine, and we have no idea what the evolved Bowman will do as he approaches the Earth. While the current scientific consensus on the inherent violence of humans is more nuanced (I note that the film also espouses the now-outdated theory about the first tools being discarded bones, suggesting that Arthur C. Clarke isn’t as up on his anthropology as he is on his astrophysics), it perhaps works well as a cautionary note about our current political situation and the possibility that we might wipe ourselves out through nuclear warfare.

2001 is a beautiful and lyrical movie which raises some interesting questions about the nature of humanity, but which also bogs itself down in the dull minutiae of an imagined life in the future. Three out of five stars.

Love At First Sight

by Victoria Silverwolf

Unlike Tony Bennett, I left my heart in Los Angeles.

I happened to be in that city during the initial run of Stanley Kubrick's new science fiction epic 2001: A Space Odyssey. I understand that the director has cut the film slightly, to tighten the pace a bit and to add a few titles to the various sequences. (The Dawn of Man at the beginning, for example.) What I saw was the original version, and it knocked me out.

Instead of just gushing about the movie, let me introduce you to the little demon sitting on my left shoulder, who will do its best to convince me I'm wrong.

Giving the Devil Its Due

ZZZZZZZ. Oh, excuse me. I fell asleep trying to watch this thing. It's got the frenzied pace of a glacier in winter and all the excitement of a snail race.

Cute. Real cute. Some people are going to consider it boring, I'm sure, compared to an action-packed film like Planet of the Apes. But that's a matter of apples and oranges. I found every second of this leisurely movie absolutely enthralling.

No accounting for taste. What about the actors? What a bunch of bland nobodies! They could be replaced with wet pieces of cardboard and you wouldn't know the difference.

First of all, let me deny the premise of your objection in at least two cases. During the Dawn of Man sequence, a fellow by the name of Daniel Richter does an extraordinary job of playing the prehistoric hominoid who discovers how to use tools. (Of course, this character isn't named in the movie itself, but I believe the script by Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke calls him Moonwatcher. We'll know for sure when the novel comes out.)

Not even the demon can deny that the makeup and costuming for this sequence is fantastic, better than in Planet of the Apes.

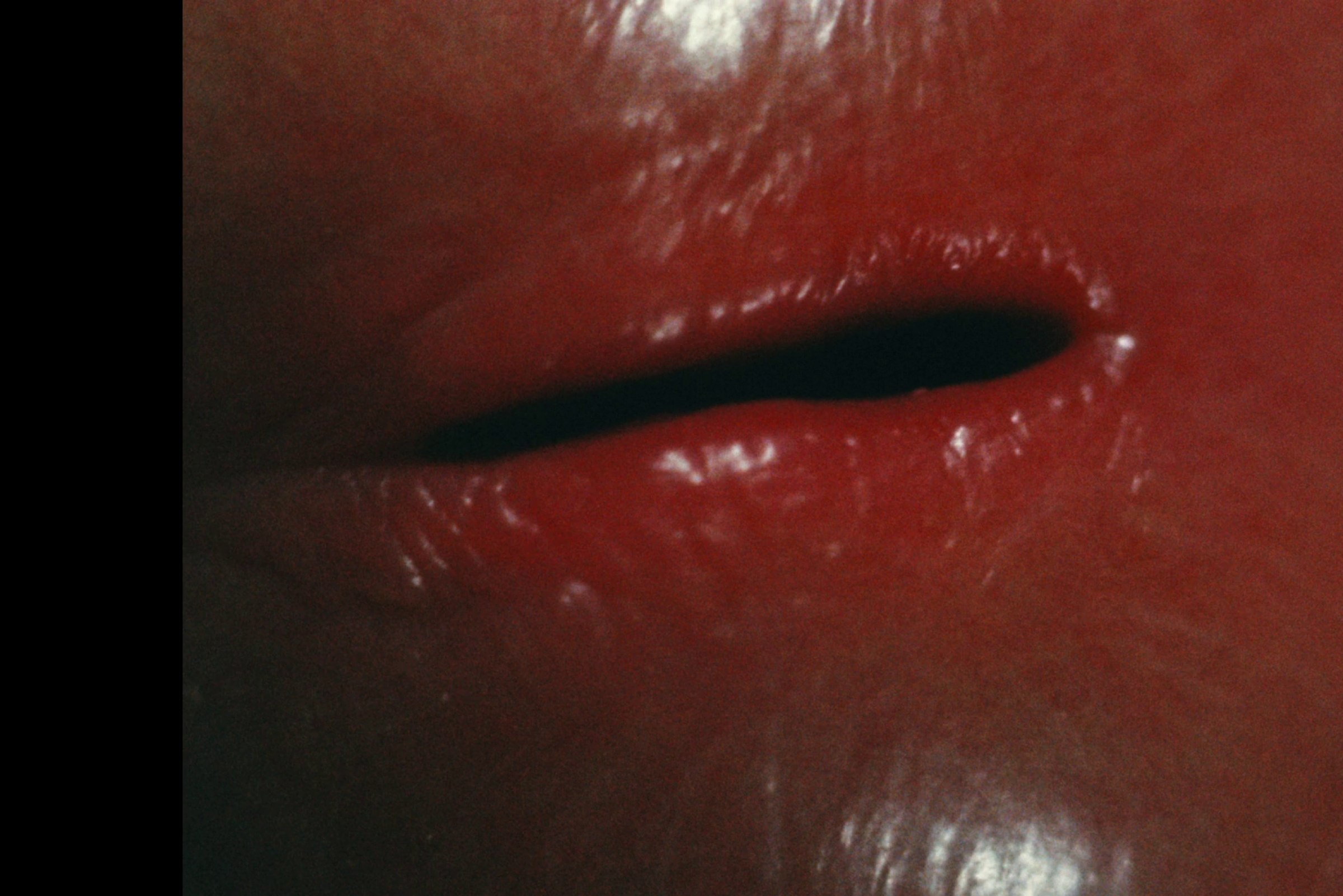

Then there's my favorite character, HAL 9000. Canadian stage actor Douglas Rain's voice is used to magnificent effect. It's exactly how I expect a sentient computer to talk.

Like everything else in the film, the design of HAL's eye is superb.

OK, I'll grant you those two. And I'll even throw in the costumes, sets, and props that appear in this turkey. But what about the actors who aren't hiding in a monkey suit or behind a glowing red circle? They're as dull as ditchwater.

Unlike Kubrick's black comedy masterpiece Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, this film doesn't have any big name stars in the cast. I think that's deliberate. Nobody is larger-than-life; they all seem like very ordinary people involved in something extraordinary.

Let's take a look at the three main human characters.

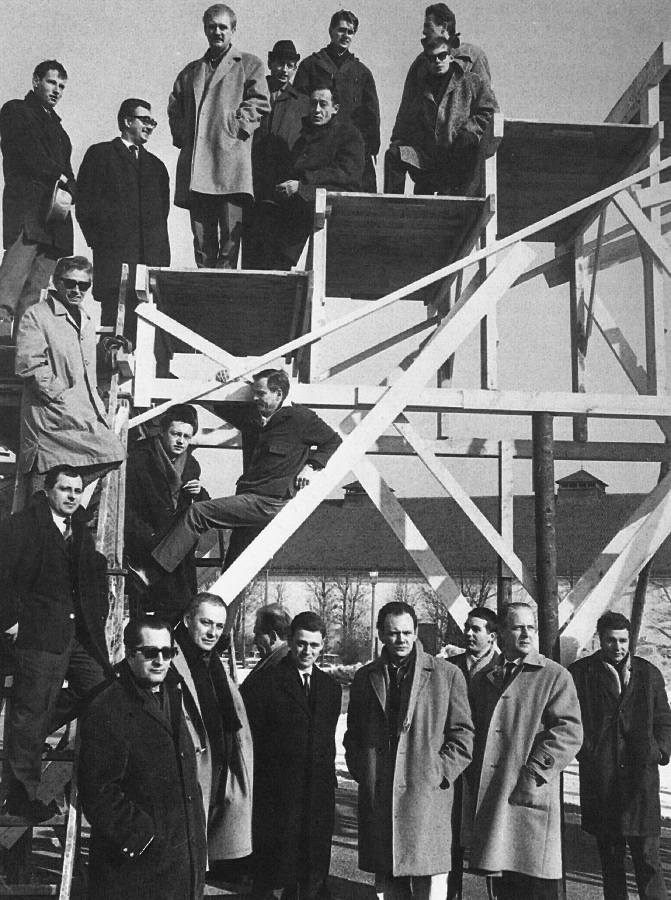

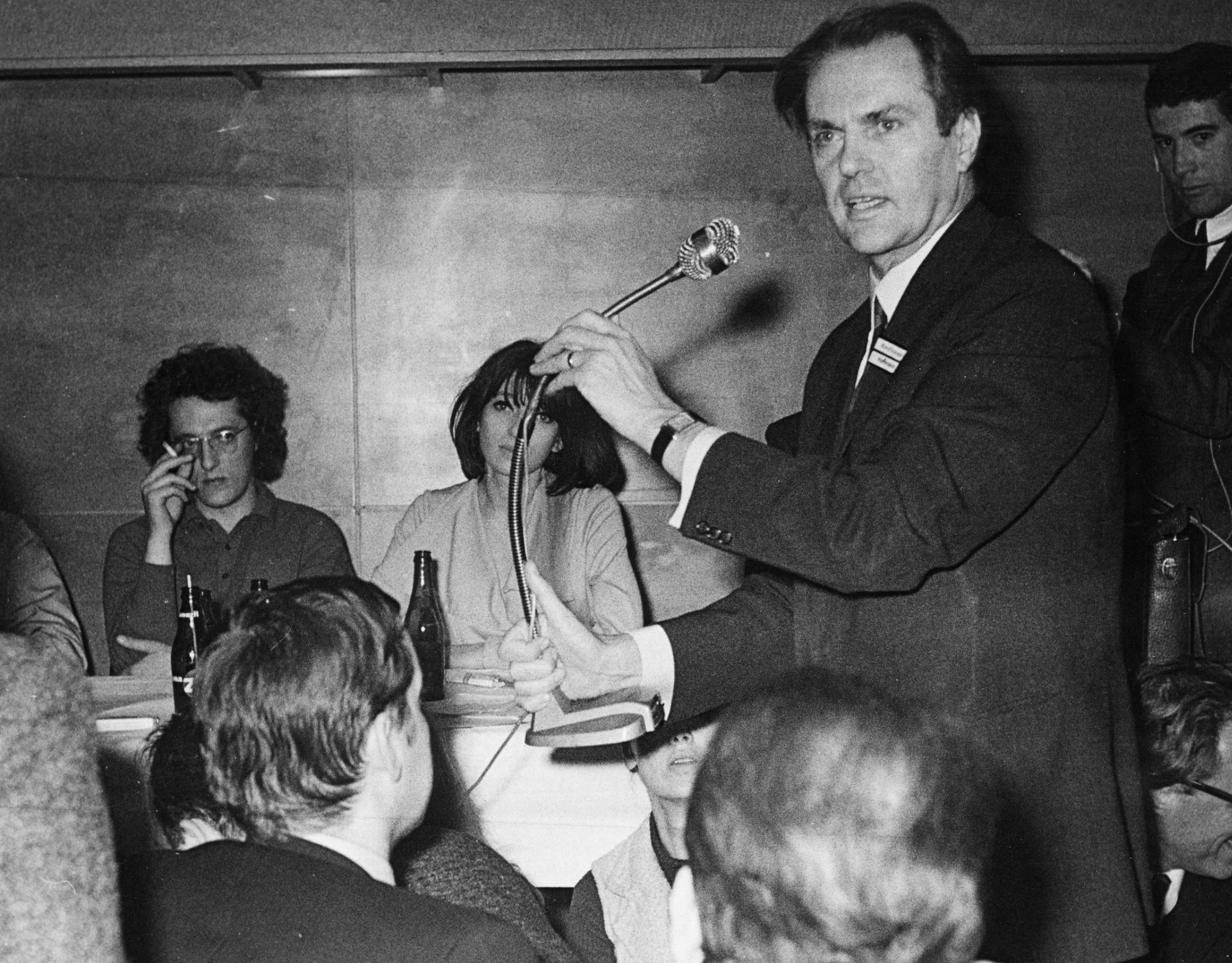

William Sylvester as Doctor Heywood R. Floyd.

William Sylvester was born in the USA but has lived and acted in the UK since the late 1940's. He's done a lot of British low budget films. I know him best for his lead roles in the horror films Devil Doll and Devils of Darkness.

Ha! And that gives him the experience to star in a multimillion dollar blockbuster? You've been watching too much Shock Theater, lady.

I can't deny that, but let me continue. Consider the two astronauts aboard Discovery in the depths of the solar system.

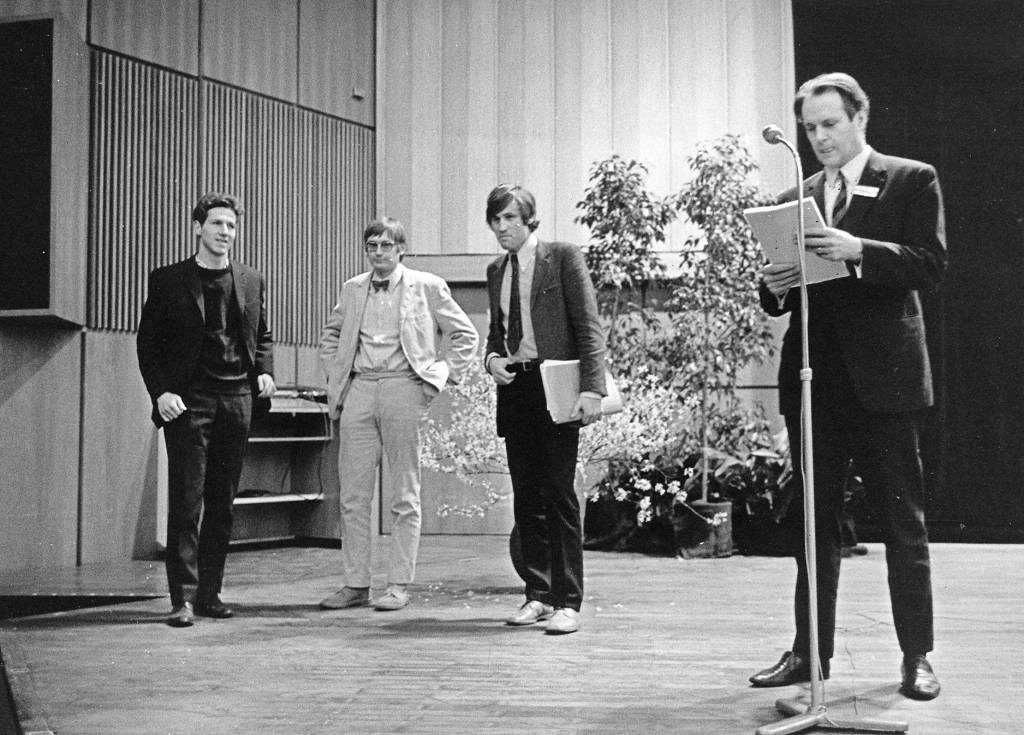

From left to right, Gary Lockwood as Doctor Frank Poole and Keir Dullea as Doctor Dave Bowman.

Gary Lockwood has done a lot of TV, and had the lead role in the fantasy film The Magic Sword. Keir Dullea has been in a few movies, and is probably best known for playing one of the two title characters in David and Lisa.

Let me guess; he didn't play Lisa. Anyway, you've just offered up two more minor league players. You're making my point for me. Where are the famous actors who would dominate the screen?

That's the problem. They would dominate the screen, and this is a movie best appreciated for its images and its ideas. You want to escape into its world, and think I am looking at the future and not There's Charlton Heston.

Point taken. So what about that goofy ending? What's that supposed to be, a San Francisco hippie psychedelic light show? Groovy, baby, pass the LSD!

I won't deny that the final sequence of the movie is ambiguous and mystifying. It's also a dazzling display of innovative film technique. In addition to what you call a light show, there's the eerie scene of Bowman in what looks like a luxurious hotel room.

A stranger in a very strange land.

What does it all mean? Don't ask me. Maybe the upcoming novel will make things clearer. But I adore this movie, and I expect to watch it dozens of times in the future, assuming it keeps coming back to second-run theaters. Maybe even if it ever shows up on TV, although it should really be experienced on a very big screen.

And the music! Goodness, what a stroke of genius to make use of existing classical and modern art music instead of a typical movie soundtrack. The Blue Danube scene alone is worth the price of admission. And the recurring presence of Also Sprach Zarathustra! Magnificent!

Five stars, and I wish I had more to give.

***sigh*** No use arguing with a woman in love.

You Damn Beautiful Apes!

by Jason Sacks

Man, who'd a thunk it? Just a couple weeks removed from seeing Planet of the Apes, there's another science fiction movie in the theatres which involves apes.

You might have heard of it, because this new film has the portentous title 2001: A Space Odyssey.

I loved Planet of the Apes. Just two weeks ago in the pages of this very magazine, I praised the film's restrained story, its tremendous special effects, its lovely cinematography and its spectacular use of music. Heck, I thought POTA was perhaps the finest science fiction movie in years. It's a thrilling, delightful sci fi masterpiece.

But 2001, man, wow, it's transcendent.

2001 is immaculate and powerful, smart and elliptical, with the greatest special effects I have ever seen in a motion picture. It tells a heady, fascinating story so vast it transcends mere humanity and expands into the metaphysical.

Many have criticized this film for being slow – heck, look at the devil on Victoria's shoulder to see just one example of that. But the slowness is obviously intentional. Director Stanley Kubrick clearly wants the viewer to see this film as stately and calm, playing astonishing space scenes juxtaposed with gorgeous classical music.

It's a work of genius to juxtapose Strauss's "The Blue Danube" with the image of a spinning space station. This juxtaposition and its stately pace allows the viewer to make connections, to see how a journey down a river in the 1860s will be as ordinary and beautiful as a journey into space in the year 2001. In the same way, using "Also Sprach Zarathustra" invites the viewer to imagine transcendence and evolution in an ecstatic way, bringing both a connection to the past and to the future in a way that perfectly suits Kubrick's themes.

Kubrick makes efforts to tether the viewer to his film with scenes like this.

What makes it even more thrilling is when he cuts that tether and demands the audience make connections ourselves.

What is the strange monolith that appears at different times of human evolution, and how does it propel us forward? Is the monolith a literal gift from alien beings (who might as well be gods – or God) or a symbol of mankind's evolution?

Why does the HAL-9000 computer, perhaps mankind's greatest achievement and an electronic being that achieves sentience, go crazy and destroy people?

What is the meaning of the trippy journey the astronaut takes towards the end of the film, and what is the meaning of the very strange place he finds himself? Why does he age? What is this place?

And what is that strange space baby we see at the end?

What do we make of any of this?

Kubrick asks the viewer to make up our own minds, to build our own interpretations of those scenes. 2001 feels overwhelming, in part, because it is participatory. This film demands we become involved with it as a means of determining some kind of truth and meaning out of it. Take this film in, interpret it, and determine your own truth. Like in life, there are no clear answers when considering the biggest questions.

Kubrick's previous film was Dr. Strangelove, a deeply cynical and polemical film (which is also hysterically funny) in which the director tells viewers what to feel. 2001: A Space Odyssey is the opposite. It's optimistic and ambiguous and highly serious. Strangelove was black and white and 2001 is glorious, rich color.

Stanley Kubrick is American's greatest living filmmaker. 2001: A Space Odyssey proves that fact.

Kubrick's film is an absolute masterpiece. Sorry, Fiona. The angel on Victoria's shoulder is right.

5 stars

![[April 26, 1968] 2001: A Space Odyssey: Three Views](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/maxresdefault-672x372.jpg)

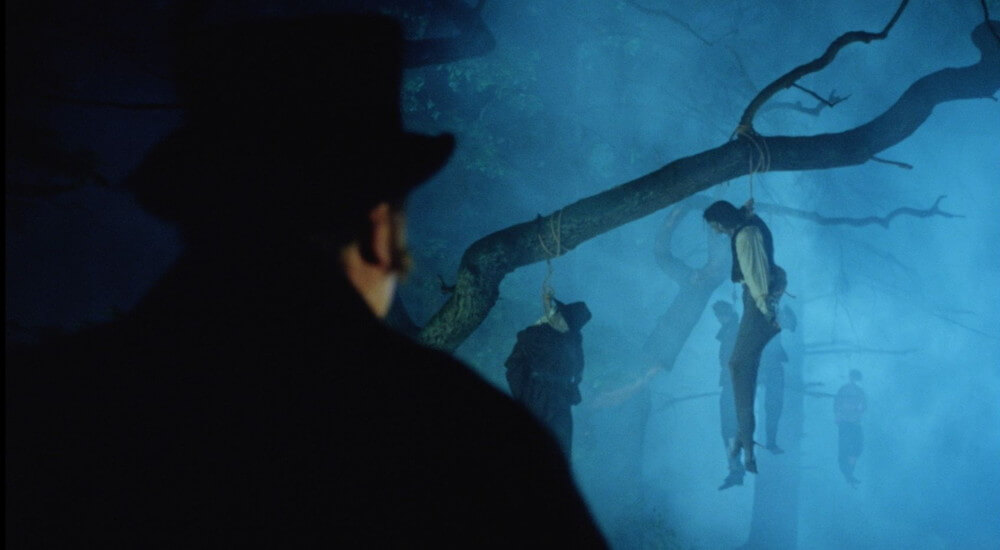

![[April 24, 1968] Terrifying Psychological Horror (<i>Hour of the Wolf</i>, by Ingmar Bergman)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/hour6-672x372.jpg)

![[April 18, 1968] "You Damn Dirty Apes!" (Planet of the Apes)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/poster-672x372.png)

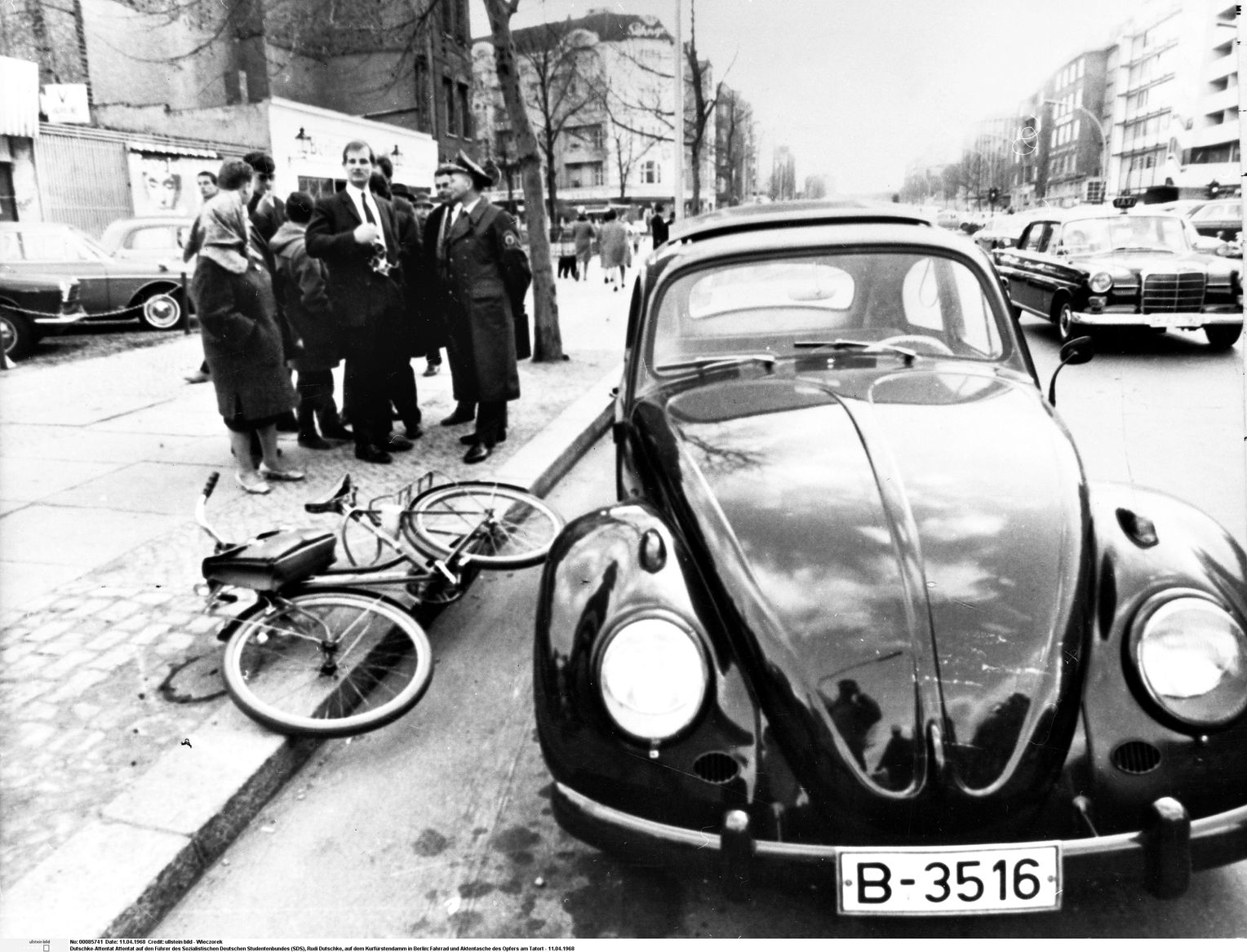

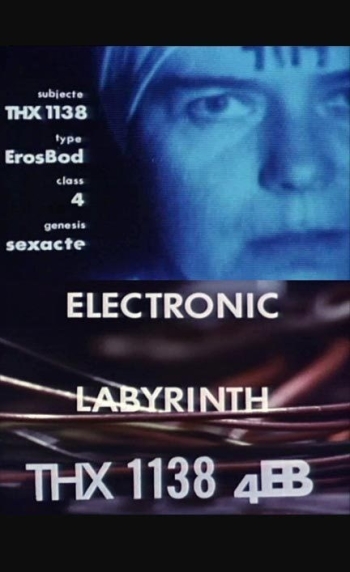

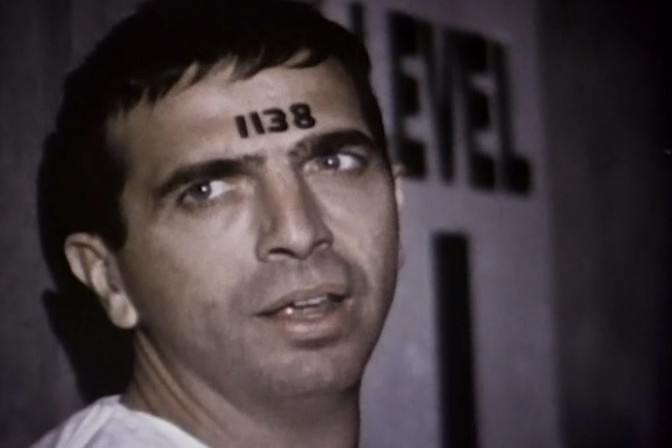

![[April 14, 1968] In Unquiet Times: The Frankfurt Arson Attacks, the Shooting of Rudi Dutschke and <i>Electronic Labyrinth THX-1138 4EB</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/THX_1138_01-672x372.jpg)

![[February 12, 1968] The Power of Cinema (<i>The Power</i>, a movie)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680212poster-672x372.jpg)

An image I'm not going to remove from my brain easily

An image I'm not going to remove from my brain easily Can *you* spot the bad guy?

Can *you* spot the bad guy? On the other hand, handsome people do get their kit off a lot.

On the other hand, handsome people do get their kit off a lot. George Hamilton about to have an encounter with a dipping bird.

George Hamilton about to have an encounter with a dipping bird. Mrs Van Zant is Japanese, and why shouldn't she be?

Mrs Van Zant is Japanese, and why shouldn't she be?![[February 6, 1968] The Most Dangerous Dame (<i>Confessions of a Psycho Cat</i>) and From the Land of Hype (Ellison's <i>From the Land of fear</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680206covers-672x372.jpg)

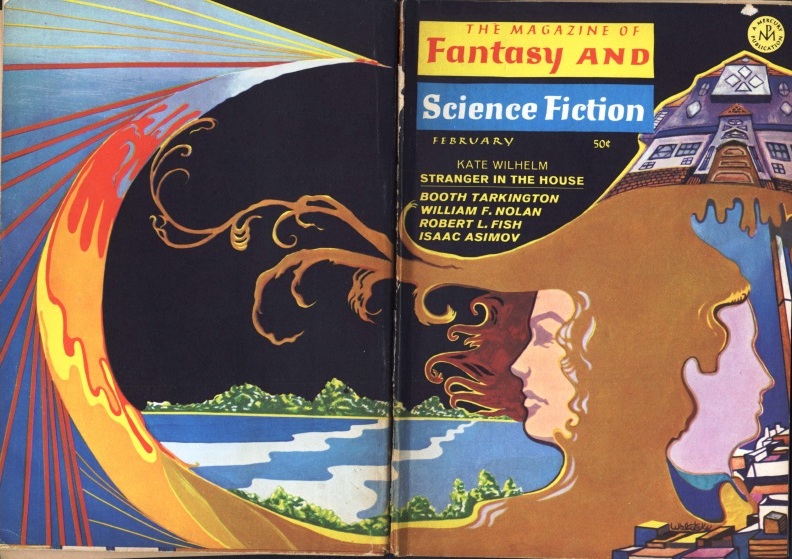

![[January 22, 1968] The Magical Mystery Tour (February 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>…plus the Beatles movie!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680122both-672x372.jpg)

The Mystery Bus attempting to flee its critics.

The Mystery Bus attempting to flee its critics. Yes, but why?

Yes, but why? Everyone having a lovely time, apparently.

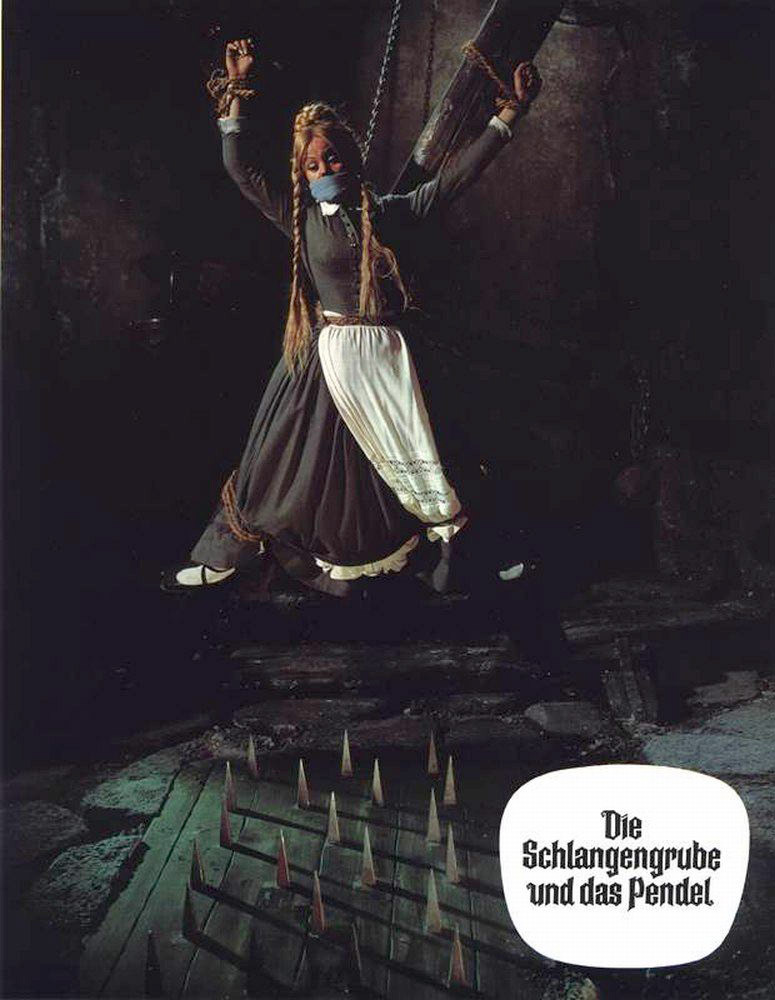

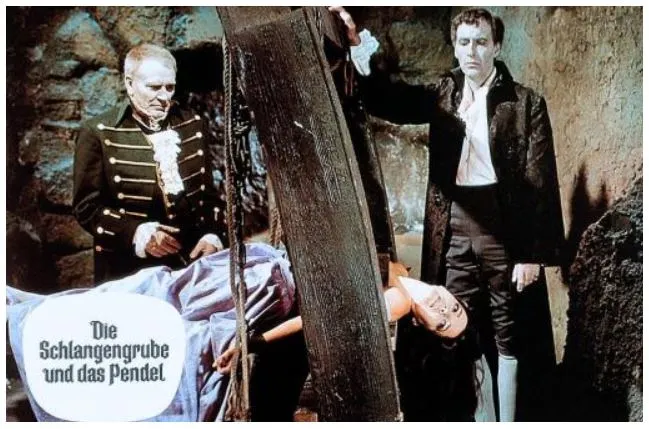

Everyone having a lovely time, apparently.![[October 18, 1967] We Are The Martians: Quatermass and the Pit, Bonnie and Clyde, The Day the Fish Came Out and The Snake Pit and the Pendulum](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671018posters-672x372.jpg)

Likeable: Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Barbara Shelley as Miss Judd

Likeable: Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Barbara Shelley as Miss Judd Colonel Breen, representing humanity's negative side.

Colonel Breen, representing humanity's negative side. Hammer's take on the Martians.

Hammer's take on the Martians.

![[August 4, 1967] Bond Movie. James Bond Movie (<i>Casino Royale</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670427casinoroyale-672x372.jpg)

In plot terms, Casino Royale is two almost entirely separate films, tenuously linked by a handful of scenes. The ‘first’ plot features David Niven as a retired, now celibate, British agent named James Bond, who is returned to service when all other agents are being killed off due to their fondness for sex. Bond recruits a new agent, Coop (Terence Cooper), and instigates an anti-sex training programme, thus allowing the movie to have its cake and eat it through sequences of Coop being sexually tempted but boldly resisting. Mata Bond (Bond’s daughter by Mata Hari) is recruited by her father and discovers a plot to auction SMERSH agent Le Chiffre’s collection of blackmail materials to various military forces from across the world, whose senior staff have been photographed in compromising situations.

In plot terms, Casino Royale is two almost entirely separate films, tenuously linked by a handful of scenes. The ‘first’ plot features David Niven as a retired, now celibate, British agent named James Bond, who is returned to service when all other agents are being killed off due to their fondness for sex. Bond recruits a new agent, Coop (Terence Cooper), and instigates an anti-sex training programme, thus allowing the movie to have its cake and eat it through sequences of Coop being sexually tempted but boldly resisting. Mata Bond (Bond’s daughter by Mata Hari) is recruited by her father and discovers a plot to auction SMERSH agent Le Chiffre’s collection of blackmail materials to various military forces from across the world, whose senior staff have been photographed in compromising situations. Meanwhile Mata and Bond travel to Casino Royale, where they discover the mastermind behind SMERSH, Doctor Noah, is in fact Jimmy Bond, Bond’s nephew (Woody Allen), who has become a supervillain through feelings of inadequacy. Noah is tricked into swallowing a pill that turns him into a walking atomic bomb and a free-for-all breaks out in the casino, with invasions by cowboys, Indians, seals, the Keystone Kops, a French legionnaire, and actor George Raft — the whole thing eventually blowing sky-high as the heroes fail to prevent Noah from exploding.

Meanwhile Mata and Bond travel to Casino Royale, where they discover the mastermind behind SMERSH, Doctor Noah, is in fact Jimmy Bond, Bond’s nephew (Woody Allen), who has become a supervillain through feelings of inadequacy. Noah is tricked into swallowing a pill that turns him into a walking atomic bomb and a free-for-all breaks out in the casino, with invasions by cowboys, Indians, seals, the Keystone Kops, a French legionnaire, and actor George Raft — the whole thing eventually blowing sky-high as the heroes fail to prevent Noah from exploding. Certain elements of the story are indeed more or less direct spoofs, either of the James Bond franchise itself or of the wider spy series craze. The film starts with a pre-credits sequence which is just a tiny scene of Bond meeting a French agent in a pissoir, simultaneously setting up and destroying expectations of a James Bond-style pre-credits action sequence. Mata Bond’s trip to Germany places her within a stage set straight out of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in a nod to the huge debt the spy film genre owes to Expressionist artform. The supporting cast includes people who’ve either appeared in Bond movies or the many independent television spy series that have cashed in on the Bond craze, notably Ursula Andress but also Vladek Sheybal and promising young character actor Burt Kwouk. As in many spy series, doubles and duplicates turn up frequently. The bizarre conceit of having all the agents, male, female, and, by the end of the adventure, animals, named James Bond/007, can be construed as a sly comment on the fact more than one actor has played Bond, or even a metatextual joke about the proliferation of code-names and numbers in such series. And, of course, the villain is motivated by a sense of personal and sexual inadequacy—what spy series villain isn’t?

Certain elements of the story are indeed more or less direct spoofs, either of the James Bond franchise itself or of the wider spy series craze. The film starts with a pre-credits sequence which is just a tiny scene of Bond meeting a French agent in a pissoir, simultaneously setting up and destroying expectations of a James Bond-style pre-credits action sequence. Mata Bond’s trip to Germany places her within a stage set straight out of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in a nod to the huge debt the spy film genre owes to Expressionist artform. The supporting cast includes people who’ve either appeared in Bond movies or the many independent television spy series that have cashed in on the Bond craze, notably Ursula Andress but also Vladek Sheybal and promising young character actor Burt Kwouk. As in many spy series, doubles and duplicates turn up frequently. The bizarre conceit of having all the agents, male, female, and, by the end of the adventure, animals, named James Bond/007, can be construed as a sly comment on the fact more than one actor has played Bond, or even a metatextual joke about the proliferation of code-names and numbers in such series. And, of course, the villain is motivated by a sense of personal and sexual inadequacy—what spy series villain isn’t? However, both plots reach their highest, as well as their lowest, moments when they embrace the surreal comedy ethos. Arguably this started with The Goon Show, of which Sellers was a key member, before really finding its home with audiences in the Sixties. Current examples of this genre include What’s New, Pussycat?, Round The Horne, the Dadaist stylings of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and At Last the 1948 Show. The trend is gaining strength: reportedly Paul McCartney is also a fan and is keen to adopt fantastical elements into Beatles films. So it’s not surprising, given the involvement of Sellers and Feldman, that Casino Royale would be taken in such a direction.

However, both plots reach their highest, as well as their lowest, moments when they embrace the surreal comedy ethos. Arguably this started with The Goon Show, of which Sellers was a key member, before really finding its home with audiences in the Sixties. Current examples of this genre include What’s New, Pussycat?, Round The Horne, the Dadaist stylings of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and At Last the 1948 Show. The trend is gaining strength: reportedly Paul McCartney is also a fan and is keen to adopt fantastical elements into Beatles films. So it’s not surprising, given the involvement of Sellers and Feldman, that Casino Royale would be taken in such a direction. The picture’s surreal comedy doesn’t always work. For instance, there’s an annoyingly self-indulgent sequence which seems just an excuse for Sellers to dress up as historical characters. Others are better: Niven’s Bond, for instance, lives on an estate guarded by a pride of lions (“I did not come here to be devoured by symbols of monarchy!” protests the Soviet head of espionage), and the idea James Bond and Mata Hari had a relationship is a somehow appropriate melding of the archetypes of the male and female spy. Mata Bond stops the auction of Le Chiffre’s compromising photos by switching the projector to a war film: as if triggered, the British, American, Chinese and Russian representatives instantly all start fighting each other, in a comment on the Cold War worthy of

The picture’s surreal comedy doesn’t always work. For instance, there’s an annoyingly self-indulgent sequence which seems just an excuse for Sellers to dress up as historical characters. Others are better: Niven’s Bond, for instance, lives on an estate guarded by a pride of lions (“I did not come here to be devoured by symbols of monarchy!” protests the Soviet head of espionage), and the idea James Bond and Mata Hari had a relationship is a somehow appropriate melding of the archetypes of the male and female spy. Mata Bond stops the auction of Le Chiffre’s compromising photos by switching the projector to a war film: as if triggered, the British, American, Chinese and Russian representatives instantly all start fighting each other, in a comment on the Cold War worthy of  Furthermore, the surrealist aspect transforms some of the problems and conflicts that arose during its production, from potential flaws to part of an overarching psychedelic atmosphere. Orson Welles had apparently insisted on performing magic tricks on camera, but these become both a send-up of the contrived “eccentricities” of spy-series villains and a deeper comment on illusion and artifice. The title sequence, which starts out as a simple riff on Bond films’ animated credits, becomes increasingly disconcerting, the imagery including walls of eyes staring pitilessly out at the viewer, with connotations of surveillance and voyeurism.

Furthermore, the surrealist aspect transforms some of the problems and conflicts that arose during its production, from potential flaws to part of an overarching psychedelic atmosphere. Orson Welles had apparently insisted on performing magic tricks on camera, but these become both a send-up of the contrived “eccentricities” of spy-series villains and a deeper comment on illusion and artifice. The title sequence, which starts out as a simple riff on Bond films’ animated credits, becomes increasingly disconcerting, the imagery including walls of eyes staring pitilessly out at the viewer, with connotations of surveillance and voyeurism. At the climax, the presence of multiple James Bonds escalates into a scenario where literally everyone becomes the titular hero; and this, together with the recurrence of doubles and duplicates, poses serious questions about how we construct our identity in modern society. At the end, everyone dies, going to Heaven or Hell, the accompanying random images and cheery music underscoring that there can be no guaranteed rescue or happy-ever-after in the atomic age.

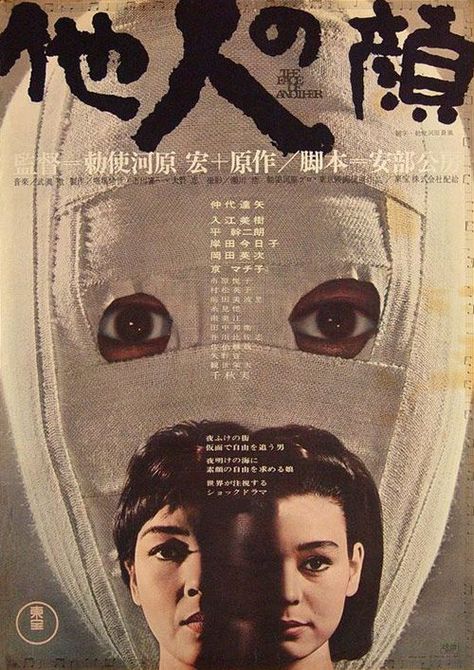

At the climax, the presence of multiple James Bonds escalates into a scenario where literally everyone becomes the titular hero; and this, together with the recurrence of doubles and duplicates, poses serious questions about how we construct our identity in modern society. At the end, everyone dies, going to Heaven or Hell, the accompanying random images and cheery music underscoring that there can be no guaranteed rescue or happy-ever-after in the atomic age.![[July 12, 1967] The masks we wear; the masks we must wear (the film: <i>The Face of Another</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/face-474x372.jpg)