by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

You might have realised that it’s nearly Christmas – again!

It has turned colder here but I’m pleased to say nothing like THAT Winter of four years ago, which has gone into the record books, I understand. Nevertheless, I do like the season, as it means I can sit at home, warm and cosy with (hopefully) a pile of good stuff to read.

Carnaby Street, London: where's the snow?

Carnaby Street, London: where's the snow?

One little shock to finish this year, however. The arrival of the latest New Worlds brings with it the usual excitement in anticipation of what I am about to read – it is pretty much a mystery at the moment, with each issue’s content rarely being predictable.

And out of all of the un-predictability, one point I wasn’t really expecting was the announcement that this issue is for TWO months – December AND January.

There were no signs of this happening in last month’s issue (other than a price increase), although I did say that there were rumours – grumblings of the publisher being unhappy, sales figures being a lot lower than expected, and editor Mike Moorcock having to go cap-in-hand to beg for more money.

Well, I might have exaggerated that last part a little. But here’s what I know. As I understand it, the ‘new’ New Worlds since it reappeared in July has been financed with an agreement between Mike Moorcock, a business partner named David Warburton and the British Arts Council, brokered by Brian Aldiss.

Facts are unclear, but evidently the take-up of subscriptions has been less – a lot less – than hoped, and so the anticipated money has not appeared. Not only that, but with such news Mike’s business partner has decided not to continue with the venture and has left Mike pretty much to it.

The money from the Arts Council has helped, admittedly, but doesn’t go far enough. The Arts Grant covers most, but not all, of the printing costs. It now seems that Mike has been paying author’s fees out of his own pocket, hoping things will improve, which haven’t. The result? Well, the price of the magazine has already gone up.

I guess that in the future these difficulties mean fewer magazines published each year, or magazines with less content and fewer pages, perhaps? It seems that Mike’s solution, at least for now until he can find more funds, is to keep up the quality but reduce the quantity.

Anyway, let’s go to the issue.

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch

Article: Free Agents and Divine Fools by Christopher Finch

A relatively short first article this month. In it Christopher looks at the year in art nearly gone and tries to point out trends and patterns. Finch’s summary is that the year’s been fairly uneventful on the surface. For Art to thrive, artistic freedom is important and is needed for art to survive, but deliberately avant garde activity seems obsolete and there is a risk of Culture becoming a sub-culture. Old class structures may be being broken down in society, but in Art in its place is a type of snobbery based on specialism. To rail against this there are a few artists, including Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton, both of whom have been in the magazine over the past few issues. There’s two pages of photos at the end to show some of their work.

Example of one of the pages of Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton art.

Example of one of the pages of Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton art.

Really, this article is a rallying call for art in the future to be outside of the systems already in place, which is pretty much the point of the new New Worlds, I think. 3 out of 5.

Bug Jack Barron (Part 1 of 3) by Norman Spinrad

An American writer who may be new to us here in Britain, although he has been mentioned here at Galactic Journey lately with his recent script for Star Trek (The Doomsday Machine) and his story Carcinoma Angels in Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions. He’s clearly a hot property at the moment, and I think this story will further add to his reputation.

Bug Jack Barron is meant to shock. It is full of expletives, overtly provocative, presenting a US in the 1980’s where the United States is often shown to be corrupt, prone to being un-democratic and riddled with corporate schemes.

This seems to follow a theme. From Ballard’s caricaturish depictions of John F Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe and Mickey Mouse, to John Brunner’s cut-up depiction of a near future New York in Stand on Zanzibar last month, it is clear that Bug Jack Barron continues this trend of anti-utopian unrest. Jack Barron is a media star who encourages anger across the country. On his nightly video show “Bug Jack Barron” he asks for, and gets, people sounding off on the concerns of the day. Jack is seen as someone whose purpose is to bring these injustices to light to the public, and gain publicity and viewers at the same time, of course!

When a caller accuses the Foundation for Human Immortality of racial discrimination by negatively discriminating against black people on Barron’s show, Jack attempts to contact live and on air the CEO of the Foundation, Benedict Howards, for a comment. However, Howards is unreachable and as a result, Jack gives air-time to negro Mississippi Governor Lukas Greene who launches into an attack on the Foundation. In an attempt to give an alternate view similar to Howards, Jack also speaks to Senator Teddy Hennering, the co-sponsor of Howards’ Freezer Utility Bill, but the result is to suggest that the Freezer Utility Bill should be cancelled. By the end of this first part, Barron begins to suspect that he may have inadvertently made an enemy in Howards, for which we must read on in the next issue.

Why is this shocking? I have already mentioned the expletive-ridden language throughout this story, which may be a little too gauche for some readers. In particular, a familiar expletive associated with those of African descent is bandied about an awful lot. This is inflammatory, vivid writing rather in the style of William Burroughs, the author so beloved by Moorcock and his colleagues. This frank discussion of race and politics in America is something a universe away from us here in Britain, although I suspect that the issues it raises are universal.

Most striking of all though is the suggestion that the media could have such an influence over a country. Could this really be a future? Could we see media monsters like Jack Barron dominate our future? I’m not sure, and certainly not in Britain, although Spinrad’s version is quite convincing.

If this is editor Moorcock’s last-hurrah, a response to his monetary struggles, it seems that he is determined to go down fighting, albeit in flames. 4 out of 5.

The Line-Up on the Shore by Giles Gordon

By comparison, the next story is much milder. One of those short stories that seem to be more a stream of consciousness than a story with a literary narrative. 58 people who seem to be stood staring until they move – or as described in the story “they run, run, run, run, run, run, run…” etc. Rather creepy, but I’m not entirely sure of its point – other than to be creepy, I guess. 2 out of 5.

Auto-Ancestral Fracture by Brian W. Aldiss and C. C. Shackleton

The return of the seemingly ever-present Mr. Aldiss (see his serial later in the issue, finishing this month), but unusually this one appears to be cowritten. This is not as it seems, however as C. C. Shackleton is a pseudonym for… Mr Brian Aldiss!

Anyway, this one is another story – or extract, I’m never quite sure – involving Colin Charteris. New Worlds insists on publishing these – the last story was Still Trajectories in the September issue – although for me they have had diminishing returns.

This time around, Colin is in Brussels, which you might know of from previous stories as having been heavily bombed with psychotropic drugs in the Acid Head War, surrounded by his disciples with his new god-like status.

Hearing two followers, Angeline and Marta, fight for Charteris’s attention as waves of reality flood in and out is rather torturous, making them sound like cast-offs from Anthony Burgess’s Clockwork Orange or devotees of Mr. Stanley Unwin’s famous gobbledegook. This also gives Aldiss/Shackleton a great chance to write about sex covertly, with words like ‘friggerhuddle’ and ‘bushwanking’, all of which seem to have been written with great glee. Edward Lear it isn’t, but I suspect an homage to James Joyce.

The last part of the story describes what happens when Cass, Charteris’s agent, persuades Colin to see famous film director Nicholas Boreas and have a film made about him. The finished film reads like a cross between something from Ken Russell and J. G. Ballard, full of fractured images and cars crashing. Afterwards Charteris continues his pilgrimage in Brussels, but things get out of hand. There’s a fire and much of Brussels burns. The story ends with eight sets of lyrics from imaginary songs.

Really don’t know how to summarise this one. The story is to be admired for its deliberately diverse styles of writing, but really not a lot happens. Like most of these Charteris stories, to me it feels incomplete, a portion of a bigger story, and as a result feels a little unsatisfying. It is better than the last Charteris story, admittedly, but that may not be saying much. Style over substance, which may be beyond most readers. 3 out of 5.

Article: Movies by Ed Emshwiller

A bit left-of-field, this one. I was pleasantly surprised that this month’s artist I have heard of, for like you perhaps, I know Ed for his artwork on magazines such as Galaxy and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. However, here this article tries to distance itself from all that pulp fiction nonsense, as it says here that in England he is best known for his film work, such as his 38 minute film Relativity, “thought by many to be about the best short film ever made.”.

Philistine that I am, I’ve never heard of it – and I suspect fans of Godard may have something to say on the matter. Anyway, this is a little different, in that it is a “primarily non-verbal description, done as a film storyboard, of his interests and aims in making films.” 4 out of 5.

Linda & Daniel & Spike by Thomas M. Disch

After Thomas’s recent serial Camp Concentration, I’m quite interested to read what fiction he comes up with next. (He has been busy writing non-fiction articles and reviews as well, admittedly.)

Linda & Daniel & Spike begins by telling us that it is a story of sex. The fact that the title is written on the back of a naked lady on the magazine cover, and the banner picture (above) may also be a clue to this. However, it is more than that. Linda tells her imaginary friend Daniel that she is pregnant with his child. Daniel walks away. Linda goes to a gynaecologist, who tells her that she is not pregnant but has uterine cancer. She gives birth to the tumour and names it Spike. Over the next fifteen years she brings Spike up, until she is readmitted to hospital for the removal of more tumours.

I get the impression that this is meant to be darkly humorous, but I didn’t find it so–just sad. It is written well, but I can’t say I enjoyed the experience. But, New Worlds is attempting to shock, and this story does that. 3 out of 5.

An Age (Part 3 of 3) by Brian W. Aldiss

Last month Edward Bush had been recruited as part of a group of soldiers from the Wenlock Institute in 2093 whose purpose was to mind-travel using the overmind back to the Jurassic and find, or arrest, or kill Silverstone, a scientist seen as a traitor by the dictatorial regime of General Peregrine Bolt.

This part begins by saying that they have had to omit chapters here and are presenting the last part of the story in a condensed form. As the book of this serial is advertised in the issue, it does feel a little like an attempt to make any interested reader go and buy the novel. There is a summary of what has gone on so far at the beginning, though, which may suffice.

Nevertheless, the story limps to an inconclusive finish. We now find that Bolt has been overthrown to be replaced by Admiral Gleeson. Bush finds Silverstone and meets him. Bush, Silverstone and a group of others mind-travel back to the Cryptozoic to avoid assassins. Silverstone then reveals his idea – that time is back to front and the future is actually our past. Silverstone is shot and killed by an assassin. The identity of the Dark Woman is revealed as someone from Central Authority and she explains the future, or rather the past. Silverstone’s body is taken away to be buried by people from Central Authority. The creation of the universe and the purpose of God is explained.

Bush and others return to the present of 2093 to explain Silverstone’s idea about the overmind to Wenlock, owner of the mind-travelling institute. Bush is put in a mental institution, allegedly because of anomia, a breakdown caused by excessive mind travel. Bush’s father tries to see him but is rebuffed. A girl (The Dark Woman? Ann?) watches him as he leaves.

A fair bit happens here. The scale is certainly epic, but the pace is rather uneven. Too much of the middle part of the story spent trying to explain Silverstone’s ‘big idea’, whilst other events feel like they happen too conveniently or too quickly. I also found the downbeat ending rather contrived and unsatisfying, leaving the story without a good ending. 3 out of 5.

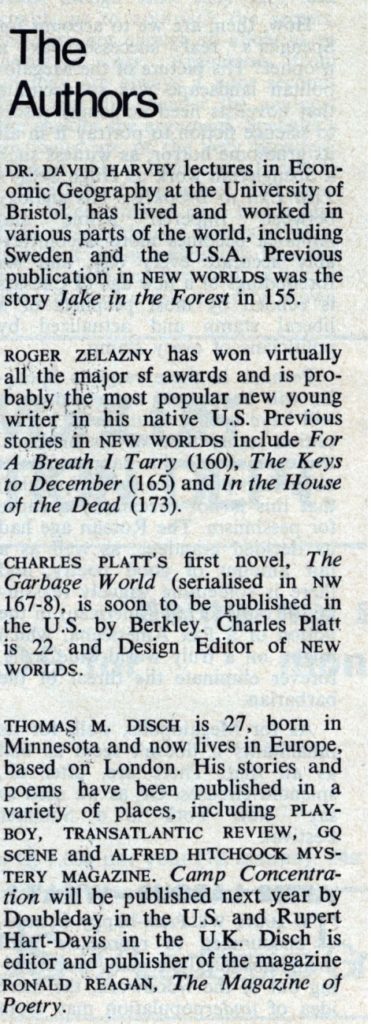

Article: Book Reviews – A Literature of Acceptance by James Colvin

This month’s Book Reviews seem to be another example of Mike Moorcock as James Colvin. He begins by examining a connection between literature – not just sf – and times of stress, postulating that the paranoia of the age is often reflected in popular writing of the time, not just now but in the past as well.

He then turns it around by claiming that change may be happening, and that – guess what! – stories like those in New Worlds may be a sign of the future and of mainstream acceptance, not just trying to entertain but to stretch and expand the genre.

The actual book reviews are for J. G. Ballard’s new collection of stories, The Overloaded Man, a reissue of Alfred Bester’s Tiger! Tiger!, Kit Reed’s first story collection, Mister da V. and Other Stories, The Seedling Stars by James Blish, Robert Zelazny’s Lord of Light and Kurt Vonnegut’s God Bless You, Mr Rosewater.

Unusually, Ballard’s collection is not given the usual glowing recommendation his work seems to get in New Worlds as it is “a poor representation of some of his early work – some of it is clumsily written and consisting principally of raw subject material that is worked in only the simplest and most obvious ways.”

The rest are generally more favourable. Taking a chance to self-promote, Moorcock/Colvin finishes the review section with a list of books coming out in 1968, many of them having first appeared in New Worlds, of course!

Article: Mac the Naif by John Sladek

This article examines the work of Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian philosopher whose style of work seems to echo much of what is being printed in New Worlds these days, in that cut-up mosaic form that Ballard and others seem to like. Even this article is written in that style.

Sladek looks at four of McLuhan’s books – The Mechanical Bride, which introduces McLuhan’s ideas of global communication, The Gutenberg Galaxy, which suggests that it is the printed word that has influenced society and ways of thinking since the Renaissance but with a McLuhan perspective, which leads to Understanding Media and his latest, The Medium is the Message, which is a condensation of his previous work and in the words of Sladek, “hardly worth reviewing” for that reason. Nevertheless, I can see that phrase becoming a mantra for all those executive advertising types in the future.

It's an interesting article, but complex, and I found I had to reread it to understand. Even Sladek admits that he doesn’t quite understand it all; whilst grudgingly admitting that there’s enough good ideas in the books to make them a worthwhile read. 3 out of 5.

There's quite a few missing here!

There's quite a few missing here!

Summing up New Worlds

We are again in a position where Moorcock seems to be determined to shake things up and is going all out to shock again this month. The Spinrad is a story I suspect would not be published in this form anywhere else. I am sure that its expletive-ridden prose, albeit with a purpose, may not go down well with the “Old Guard of Science Fiction”, but would have made an ideal choice for Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions collection, had it been shorter and a story from Spinrad not already accepted. Like Ellison, I think Spinrad has an exciting future ahead.

It actually is quite a surprise to realise that this is the same writer who wrote the script for the Star Trek episode "Doomsday Machine" – they are very different and show that the writer has a range. Obviously, this is only the first part, but I think it shows that in the future Spinrad could be up there with Samuel R. Delany at his most impressive.

The Disch also seems determined to shock, but I don’t think that it is as good as his previous work. I am now feeling that, even with my reservations about it, the rest of his writing tends to pale in significance against Camp Concentration.

Both Aldiss stories disappointed. Although I enjoyed Auto-Ancestral Fracture more than most of the others of his Charteris stories, it still was as unsatisfying as I had feared. An Age finished weakly.

But all in all, a good issue that seems to defiantly tread the path in the new direction the magazine is taking. Whilst there were parts that left me feeling dissatisfied, it must be said that it made me think. There’s a lot of things here as in recent issues that definitely make you think beyond the confines of the magazine, which in my opinion is good, but may be the magazine’s downfall. Extra cerebral activity may alienate some of the readership the magazine hopes to acquire.

Certainly, based on what I’m reading here, there are few signs that this will be the last issue – after all, the magazine feels confident enough to start a new serial this month. Hopefully this means that things financially will be resolved soon, and the magazine will continue.

It was interesting that the magazine put this at the back:

And that’s it from me for this year. All the very best to you all, have a wonderful Christmas and I’ll get back to you in the New Year (hopefully!)

President Johnson signing the law allowing women to rise in the ranks.

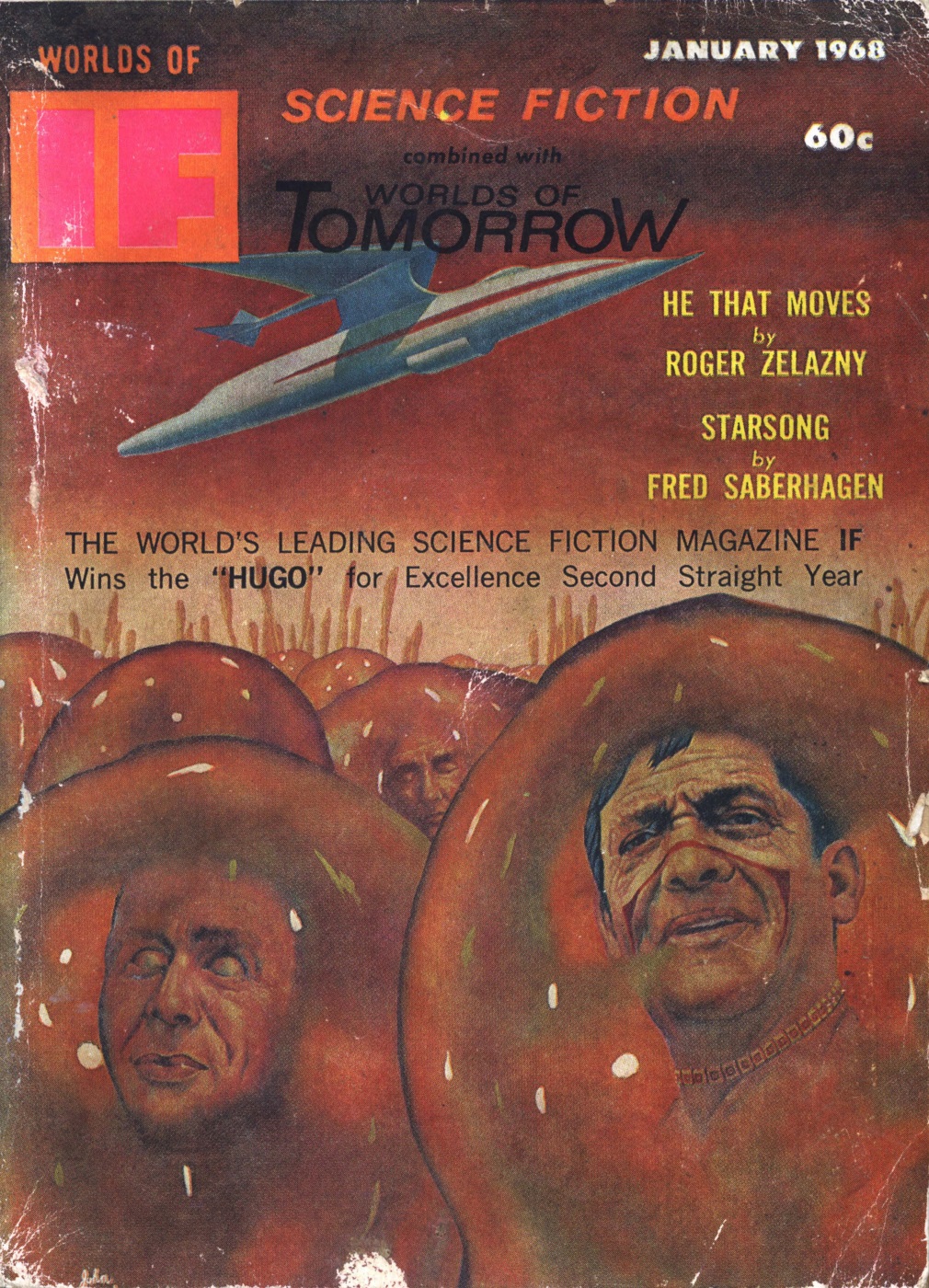

President Johnson signing the law allowing women to rise in the ranks. What are these people doing in these blobs? Art by Pederson

What are these people doing in these blobs? Art by Pederson

![[December 2, 1967] Women and Men (January 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/IF-1968-01-Cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 30, 1967] One door closes… (December 1967 <i>Analog</i> and Australia joins the Space Race!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/671130cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1967] The Shock of the New – Part 3 <i>New Worlds</i>, December 1967 – January 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/new-worlds-dec-67-672x372.jpg)

Carnaby Street, London: where's the snow?

Carnaby Street, London: where's the snow?

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch Example of one of the pages of Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton art.

Example of one of the pages of Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton art.

There's quite a few missing here!

There's quite a few missing here!

![[November 20, 1967] Fresh Air? (December 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/amz-1267-cover-497x372.png)

![[November 4, 1967] Conflicts (December 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/IF-1967-12-Cover-672x372.jpg)

Joan Baez is arrested in Oakland.

Joan Baez is arrested in Oakland. Fr. Berrigan pouring blood into a file drawer.

Fr. Berrigan pouring blood into a file drawer. Futuristic combat in The City of Yesterday. Art by Chaffee

Futuristic combat in The City of Yesterday. Art by Chaffee![[October 24, 1967] War, Anti-utopias and Near-Future Apocalypses <i>New Worlds</i>, November 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/New-Worlds-November-1967-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Vivienne Young

Cover by Vivienne Young An example of the logic shown in this article. Not sure I understood this!

An example of the logic shown in this article. Not sure I understood this!

Example of Self's imagery.

Example of Self's imagery. Uncredited image, but it looks like a Douthwaite, who is credited in the magazine.

Uncredited image, but it looks like a Douthwaite, who is credited in the magazine. Another uncredited image that looks like a Douthwaite.

Another uncredited image that looks like a Douthwaite. Sharing the horror in full – another poetic gem – well, they seem to be liked by some!

Sharing the horror in full – another poetic gem – well, they seem to be liked by some! Illustration by Cawthorn

Illustration by Cawthorn The future of energy?

The future of energy?

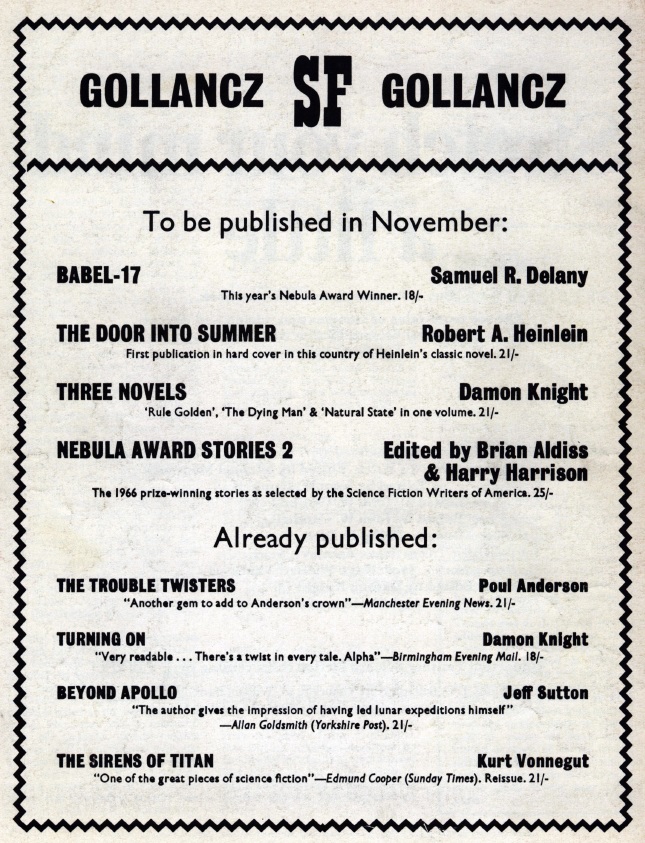

An advertisement from this month's magazine that shows how different book sales and New Worlds magazine is, perhaps? How many of these authors are mentioned in detail in the magazine these days?

An advertisement from this month's magazine that shows how different book sales and New Worlds magazine is, perhaps? How many of these authors are mentioned in detail in the magazine these days?![[October 2, 1967] Switching Sides (November 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/IF-1967-11-Cover-672x372.jpg)

The logo for the traffic changeover.

The logo for the traffic changeover. This photo was staged several months ago as part of the education campaign. The real thing was much less chaotic.

This photo was staged several months ago as part of the education campaign. The real thing was much less chaotic. A newcomer gets the cover. Does he deserve it? Art by Vaughn Bodé

A newcomer gets the cover. Does he deserve it? Art by Vaughn Bodé![[September 30, 1967] Ain't that good news! (October 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/670930cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 26, 1967] Anniversary? Really? <i>New Worlds</i>, October 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/NW-October-1967-672x372.jpeg)

Yes: people are willing to go to war over Baked Beans!

Yes: people are willing to go to war over Baked Beans! A page showing some of Peake's imaginative artwork.

A page showing some of Peake's imaginative artwork. This illustration seems to sum up this odd story.

This illustration seems to sum up this odd story.

![[September 2, 1967] Of Genies and Bottles (October 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IF-Cover-1967-10-672x372.jpg)

William C. Foster, the chief American representative to the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament.

William C. Foster, the chief American representative to the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament. The art is intriguing, but none of this happens in Hal Clement’s new novel. Art by Castellon

The art is intriguing, but none of this happens in Hal Clement’s new novel. Art by Castellon