by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again.

A recent comment from our leader here at Galactic Journey caused me to pause for thought. As he summed up the year in science fiction, it struck me that we are about to end one year (not that un-obvious, admittedly) and about to begin the last year of the decade, in what must be one of the most significant decades in recent human history.

Personally, the near-end of the decade seems to have crept up on me, but I can’t deny that it has certainly been eventful. Who knows, judging by all the recent activity (e.g. the Apollo missions!) we could be seeing people on the Moon in the next couple of years. Wouldn’t that be wonderful?

Anyway, I digress. My point is that I was suddenly made aware of how much things have changed in the last decade.

Which in a roundabout way brings me to the many changes involving New Worlds in the last few years. The New Worlds of 1968-69 is a very different beast from that of ten years ago. Some will say ‘better’ – more intelligent, more literary, more complex, more adult in nature – whilst others will say ‘worse’ – perhaps summarised as “Where’s my Science Fiction?”

After reading Gideon’s final article of November, I wrote him a letter, noting:

“More seriously, despite my personal grumblings, New Worlds is miles ahead of what the magazine used to be, even if its science-fictional content varies enormously. Much more inner space than outer space these days.

And there’s a whole debate over whether we can count it as an SF magazine any more – many of its older readers think not! – but it is noticeably different to pretty much anything else out there at the moment. I do hope that New Worlds can keep going next year, although it's not entirely certain.

That applies not just to the US but to Britain as well, of course – there is no other magazine to compare it to, as all the others have been cancelled!"

This year exemplified that range of content. In the last issue alone we had, on one hand, the stunning Samuel R. Delany story, Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones, which I am still thinking about, and on the other a story about a man repeatedly raping a paralysed patient and making her pregnant. Talk about eclectic….

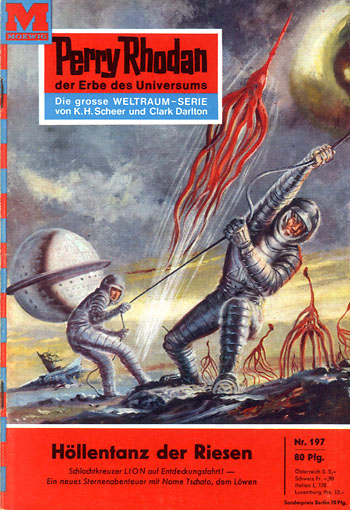

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

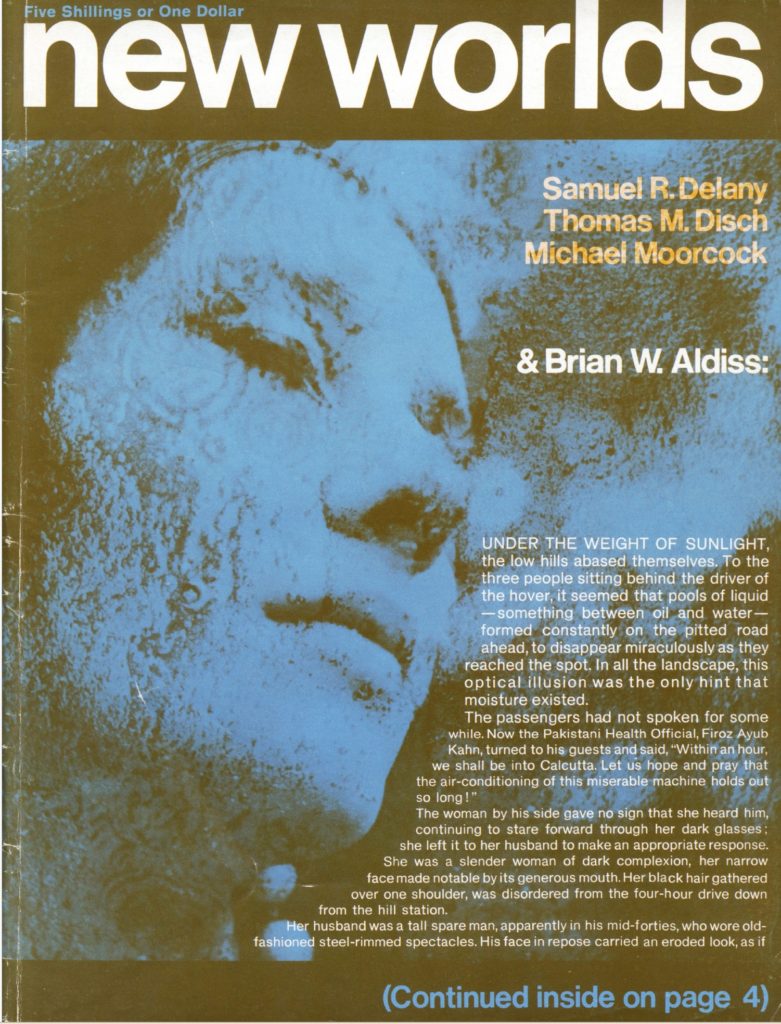

Anyway, this month’s issue feels like the return of the old guard. Although the cover is in the new format started last month – a strangely coloured but generic photo of two heads, text from one of the main stories within – the roster of authors is mainly the usual. Even these stories are mostly connected to previously published stories… more later.

Lead In by The Publishers

More about the contributors this month: Ballard, Disch, Langdon Jones. They also sneak in an apology for the contents of this issue being different to what was expected due to the Post Office delivering the manuscripts too late for publication. Hmm.

The Tank Trapeze by Michael Moorcock

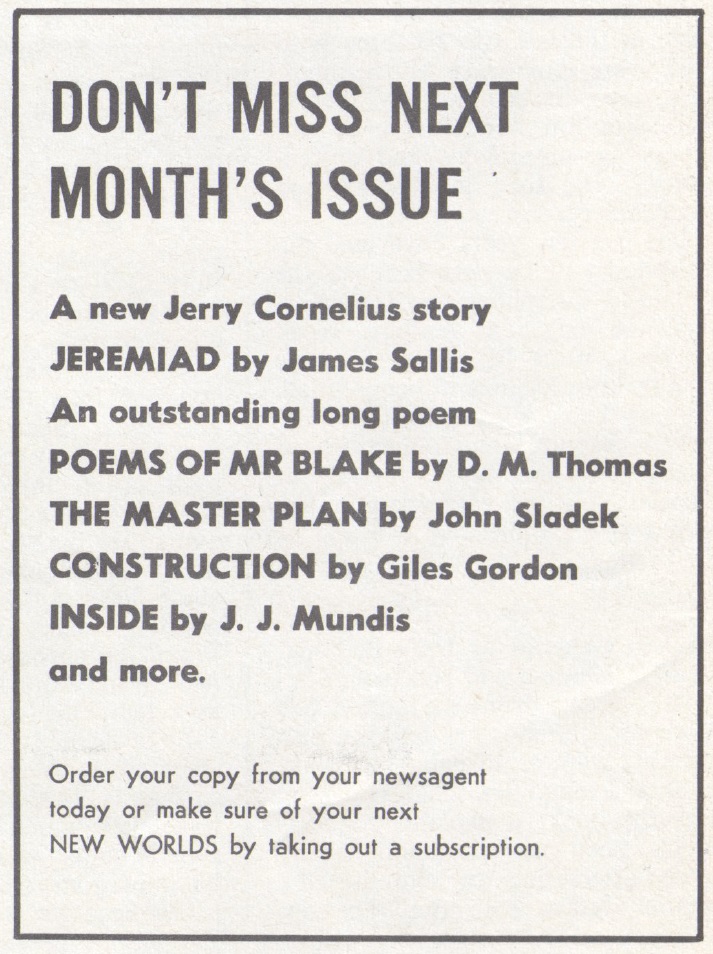

Last month the magazine declared that Mike Moorcock’s character Jerry Cornelius would continue in future issues by stories written by others, starting with James Sallis’s Jeremiad.

For whatever reason this hasn’t happened, and so we get a story from Jerry’s originator instead, the sixth by my reckoning. And we’re straight into contemporary issues, with assassin-for-hire Jerry being in Czechoslovakia whilst the Russians take over the country. Jerry plays cricket whilst Dubrovnik burns, seduces (or is seduced) by a woman and executes a young boy-monk, who may or may not be important. Memorable, shocking, surreal – a typical Jerry Cornelius story. 4 out of 5.

Anxietal Register B by John T. Sladek

Back in the April 1968 issue Sladek wrote New Forms, an increasingly surreal fictious form. It was amusing and quite popular (I liked it.) As befits the current mood of this issue, if it works once, why not do it again?

This time it is about testing how anxious you are. Mundane responses are encouraged amongst shockingly provocative ones – “Have you ever suffered from: arthritis… rheumatism…homosexual tendencies” etc. It is still amusing, but its impact is diminished as the shock novelty value of the first time is less of a surprise second time. 3 out of 5.

Epilogue for an Office Picnic by Harvey Jacobs

A story in the form of a unrequited love letter between "Bald Mr. X from Data Processing" to "Sherill" – or Sheril, or Sherrill – the writer isn't sure. An odd tale that's meant to be amusing. I just found it sad. 2 out of 5.

The Summer Cannibals by J. G. Ballard

Ah, J. G. “Chuckles” Ballard. Lots of imitators of late, none really of his ability. After the last few stories by him have underwhelmed me (see The Generations of America in the November 1968 issue), we’re back into a better story of Ballard’s usual observational descriptions of societal bleakness – sex, cars, money, belongings, the American lifestyle. (Anybody else notice how often Ballard’s characters are just walking?)

With its sections of different prose styles, photos and sheer oddness, this is a better piece of work than his last one, although I’m not quite sure about the strange juxtaposition of sex and car parts. (Really. Try reading the section entitled “Elements of an Orgasm”.)

As perplexing yet as iconic as ever, The Summer Cannibals is typical Ballard and therefore welcome, if only to be brought down by the point that this is like Ballard-things we’ve read before and – of course! – another extract of something that will soon be a novel. Does it matter? Echoing the tone of Ballard – not really. Appreciate the style, consider the content. 4 out of 5.

Spiderweb by John Clute

An author we’ve read before, back in the November 1966 issue, but has been very quiet since. This seems to fit the current New Worlds template – a surreal story of love, sex, race and graphic hallucinations, although mainly sex. Vivid imagery. Bug Jack Barron has a lot to answer for by setting a standard for this sort of thing. 3 out of 5.

Article: Sim One by Christopher Evans

The welcome return of Dr. Christopher Evans brings us an interesting article about how close we are to creating a life-like human robot. I think Asimov would be pleased at the progress, but I keep thinking about Philip K. Dick’s stories about simulacra and personally am a little horrified. 4 out of 5.

Hospital of Transplanted Hearts by D. M. Thomas

Erm.. poetry warning. If you’re a regular reader of my reviews, you know my general view on poetry. But perhaps you know more about it than I do, New Worlds reader.

Just to be clear – New Worlds editors really like D. M. Thomas. As in, REALLY like. Declaring the poet to be “without question, one of England’s very best poets” in the Lead In, they like this particular poem so much it is available as a poster, courtesy of Charles Platt.

Just to be clear – New Worlds editors really like D. M. Thomas. As in, REALLY like. Declaring the poet to be “without question, one of England’s very best poets” in the Lead In, they like this particular poem so much it is available as a poster, courtesy of Charles Platt.

Here, I’m less enthused. This was the ‘poet’ who wrote that awful Mind Rape poem back in the March issue, after all, but I try not to let that affect me.

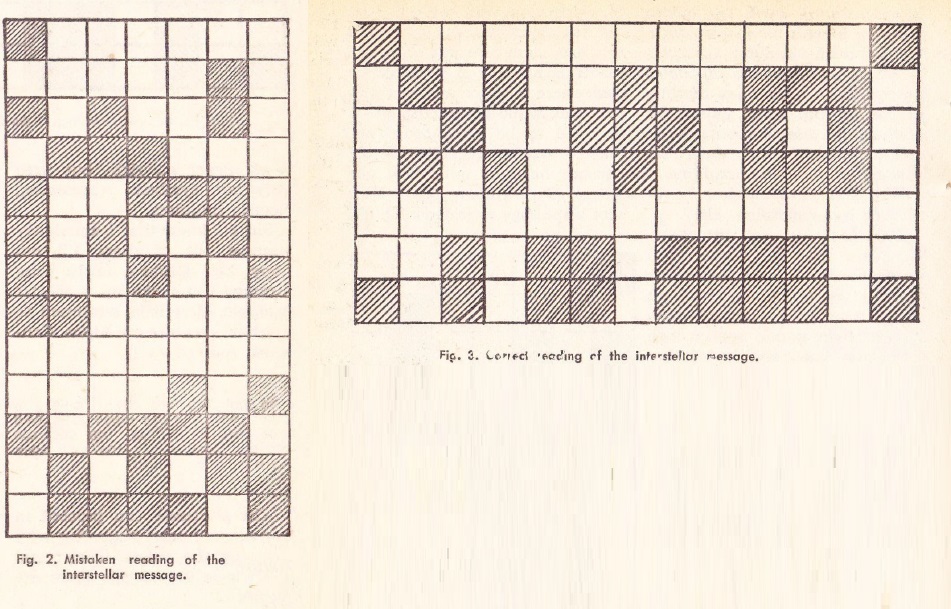

Here the poem is like a pick and mix jumble of statements and phrases so you can make up your own as you skip through the Battleships-type grid. It is amusing, but less important than it would like to be. It is certainly not an event on the scale of the Second Coming of the Messiah that New Worlds seem to want to create. (How’s that for a Christmas reference?)

The thing about creative work such as poetry is that people often passionately agree or disagree about such things. This may be a case in point. Others may love it – me, less so. 3 out of 5.

Juan Fortune by Opal Nations

A story in deep homage to Ballard here – broken into sections, with lists of characters WRITTEN IN CAPITAL LETTERS like a play…and (of course!) all about sex. Seems pointless to me. (the prose, not sex!) 2 out of 5.

Ouspenski’s Astrabahn by Brian W, Aldiss

It hurts to write about this one. “The longest part of the Charteris series”, it says in the Lead In, about to be published as a book. As a series I have grown to actively dislike, I have little to say on this one. Yes, it’s clever, and as ever with Aldiss, well written. But at the same time, it’s an incomplete extract of a story that may make little sense if you haven’t read the previous parts and secondly, it degenerates (like some of the previous parts) into a variety of prose styles that I can only politely describe as stylistic gobbledygook.

Does the story, such as it is, make sense? Is it worth my time? In the end I didn’t care about the characters, the setting or the story.

Others will disagree, I’m sure – I’m just pleased that this, whatever it is, is finished, and I can move on (see also Bug Jack Barron earlier this year too.) 2 out of 5.

Book Reviews

J.G. Ballard reviews The Voices of Time by J. T. Frazer in a very Ballardian way, Langdon Jones reviews Silence by John Cage as if it was a questionnaire, John Brunner reviews four psychology books published by Allen Lane, whilst at the same time trying to persuade me that as a reader of science fiction I should read such books (I’m personally not too convinced), and William Barclay reviews Jack Trevor Story’s books, an author I only know because of Hitchcock’s film of his novel, The Trouble With Harry.

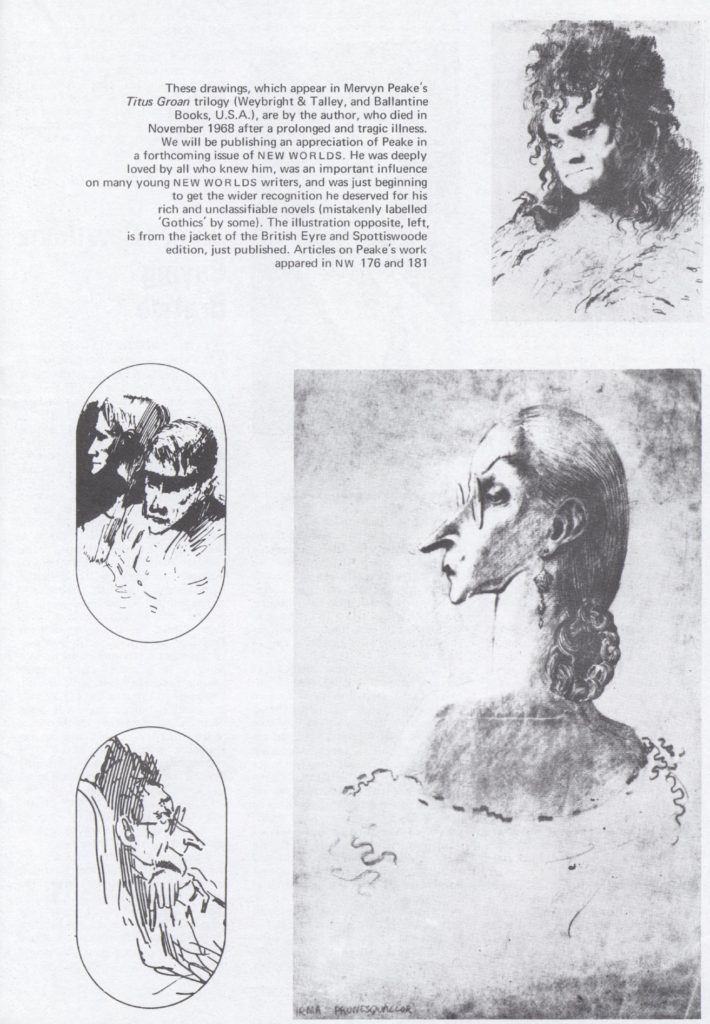

It is left to James Cawthorn to review some British science fiction books, although Thomas M. Disch reviews Quicksand by John Brunner. Joyce Churchill (who I believe is a pseudonym for M. John Harrison) briefly reviews a bunch of anthologies and John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar. Langdon Jones also gives us the sad news of Mervyn Peake’s recent death, illustrating it with some of Peake’s drawings.

Summing Up

I think Moorcock and his team have been pushed to get an issue out this month. (Perhaps they’ve been Christmas shopping instead?) Whilst Langdon Jones has been away, his absence, not to mention the effect of Post Office delays, as mentioned in the Lead In appears to have led to what feels like an issue cobbled together from remainders from old established authors with nothing really new to say, just finishing off what has already been started.

I realise that some readers may see the issue as a comfort, as in the return of old friends, but to me, it is like a shop clearing the shelves of tired, old stock ready for the new year. The Ballard is entertaining, but even then just a variation on a previous theme. I’ve said on many previous occasions (even last month!) how much I’ve come to dislike Aldiss’s Charteris stories, and it doesn’t help that this conclusion fills up much of the issue. At least the Jerry Cornelius was good.

I know that there are readers that will love both the Ballard and the Aldiss and even D. M. Thomas’s ‘poem’, but not me, sadly. The standard has been raised so much in recent years that it is almost a given now that each issue of New Worlds will surprise, amuse, antagonise and annoy. For the first time in a long time, this issue for me has really let me down.

Really the only good thing I can say about the issue is that at least these series are finished, and as the new year begins, we can look at new material in the future – looking forward, not backward. Rather appropriate for the end of one year and the beginning of the next, I think.

On a more positive note, have a great Christmas, and I look forward to returning next year when (hopefully) I will be less grumpy. “Bah, Humbug!” and so forth.

On a more positive note, have a great Christmas, and I look forward to returning next year when (hopefully) I will be less grumpy. “Bah, Humbug!” and so forth.

I'm off to look at the Christmas Radio Times to cheer myself up and see what's worth watching and listening to (Morecambe and Wise?)

Until next time!

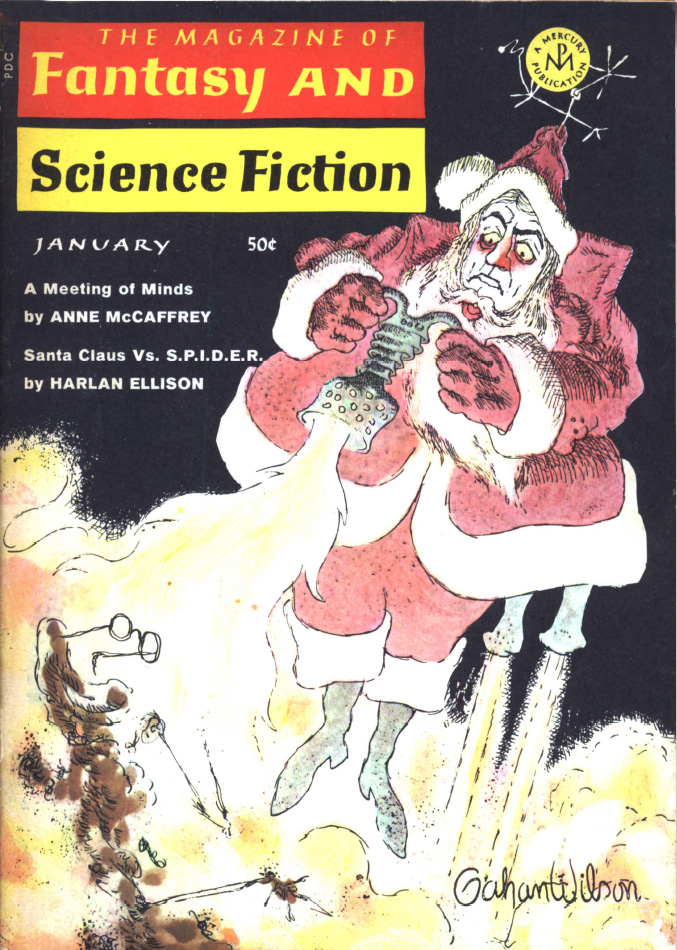

![[December 22, 1968] What wonders await? (January 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681222cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 10, 1968] Back and forth (January 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681210cover-671x372.jpg)

![[December 8, 1968] Hippies and Robots (July-December 1968 Playboy)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681212covere-672x372.jpg)

![[December 4, 1968] Sign Me Up (January 1969 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/amz-0169-cover-355x372.png)

![[December 2, 1968] Forget It (January 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/1969-01-IF-cover-560x372.jpg)

Leonid Brezhnev after addressing the Soviet Central Committee earlier this year.

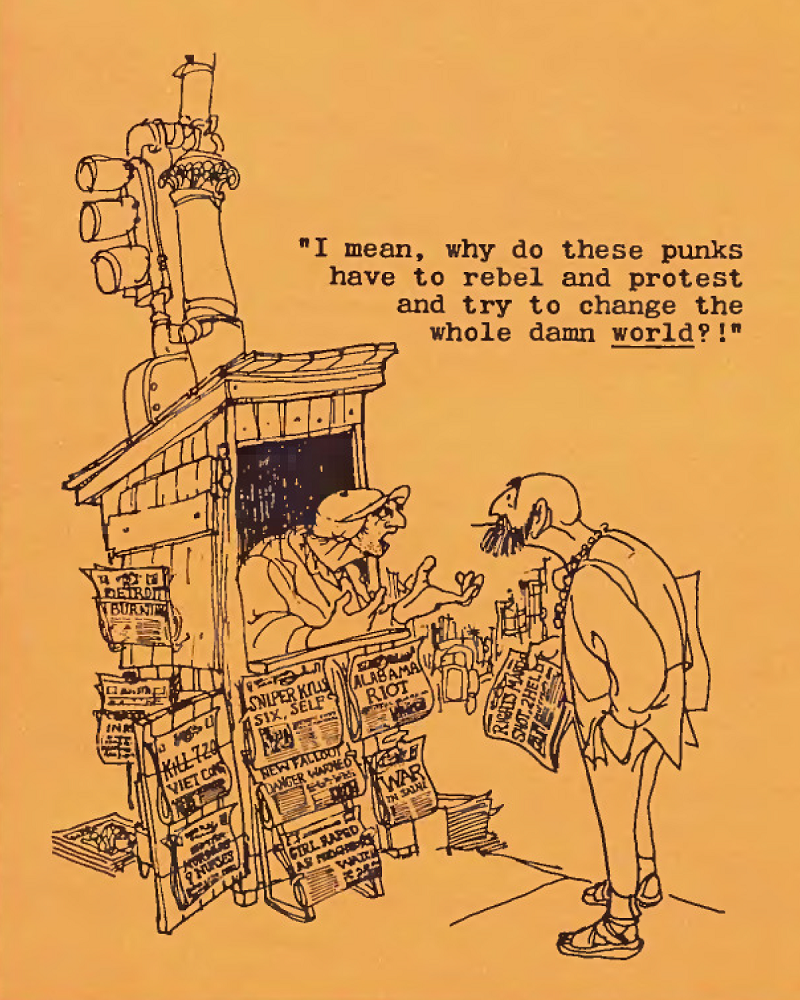

Leonid Brezhnev after addressing the Soviet Central Committee earlier this year. Just some random art not associated with any of the stories. Art by Chaffee

Just some random art not associated with any of the stories. Art by Chaffee![[November 30, 1968] Up, Up, and Around! (December 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681130cover-575x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1968] Warhol, Delany, Cornelius and Perversity <i>New Worlds</i>, December 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/new-worlds-december-1968-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Picture by James Cawthorn

Picture by James Cawthorn

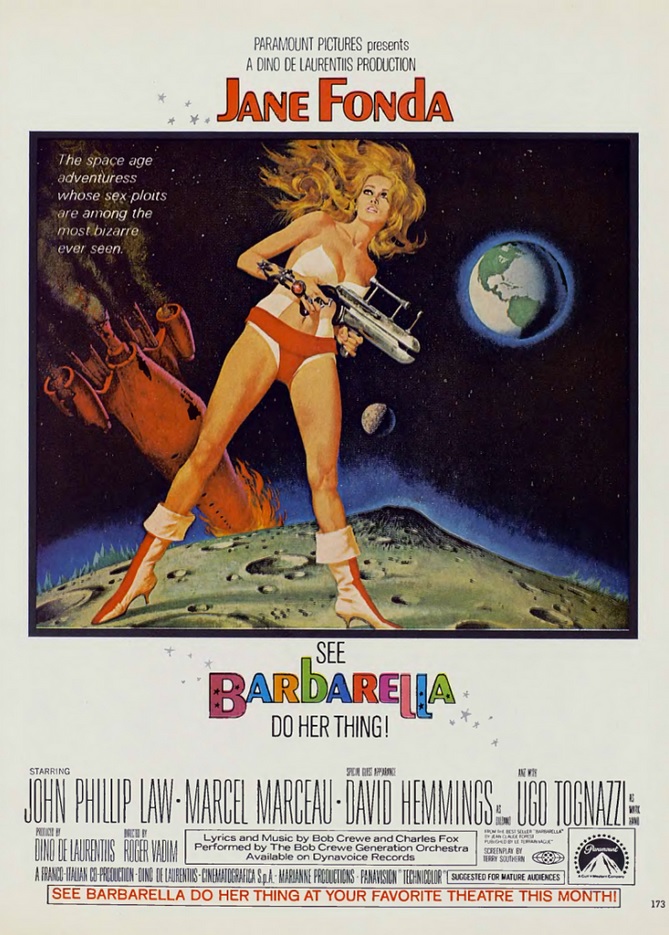

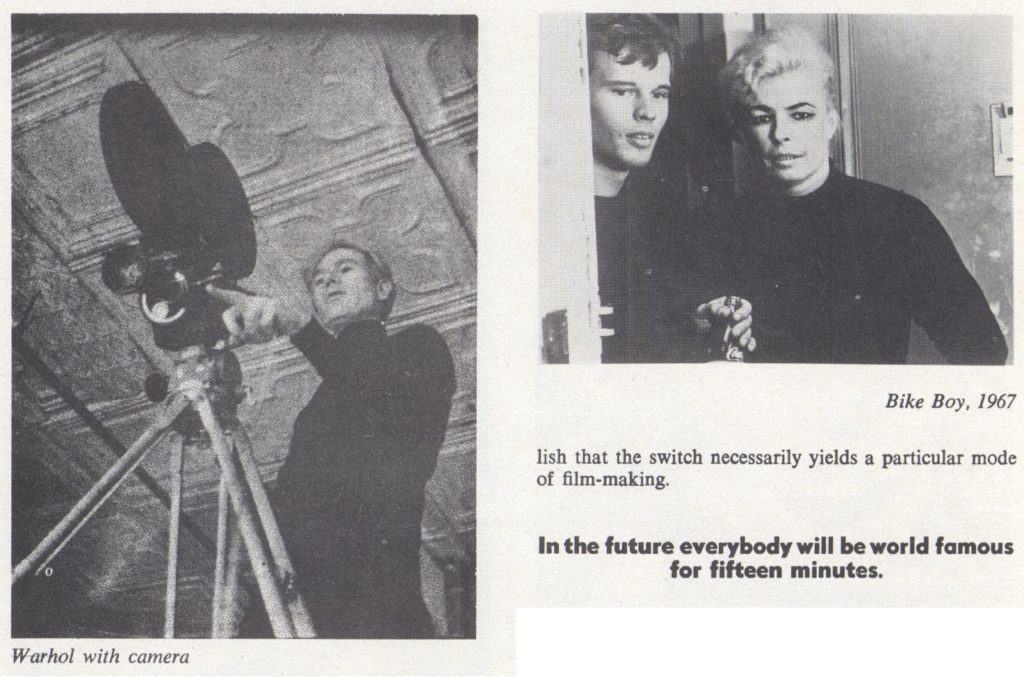

(And where would New Worlds be without a provocative photo or a mention of J. G. Ballard? This is an advertisement on the back cover.)

(And where would New Worlds be without a provocative photo or a mention of J. G. Ballard? This is an advertisement on the back cover.)

![[November 20, 1968] Transitory and lasting pleasures (December 1968 <i>F&SF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681120cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 10, 1968] Ratings (December 1968 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/COVERREDUCED-672x372.jpg)