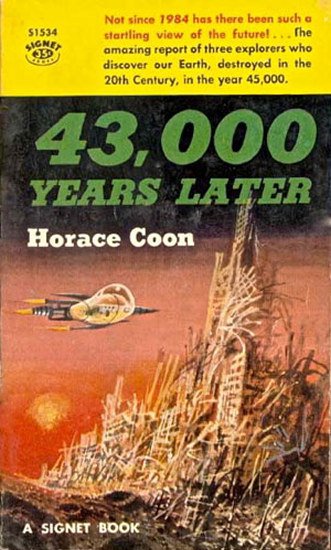

Two years ago, the Soviet Union demonstrated the ability to lob an H-bomb across the globe. Overnight, it was clear that anywhere on the planet could be destroyed with just 15 minutes' notice, if that. This year, the United States will base Thor and Jupiter IRBMs in Europe within range of the Soviet Union, and the Russians will feel that same Sword of Damocles. Never mind that America's Strategic Air Command has more bombers now than ever, and one can be fairly certain that the Soviet counterpart is at a historical high, as well.

Civilization could all come crashing down at a moment's notice. It's a reality we've lived with since that first artificial sun blossomed over the desert of New Mexico, but it's never been closer, more tangible.

An atomic holocaust has been the subject of numerous novels and short stories since the late 1940's, but until this year, there had not been a grittily realistic portrayal of a nuclear exchange and the subsequent struggle for survival.

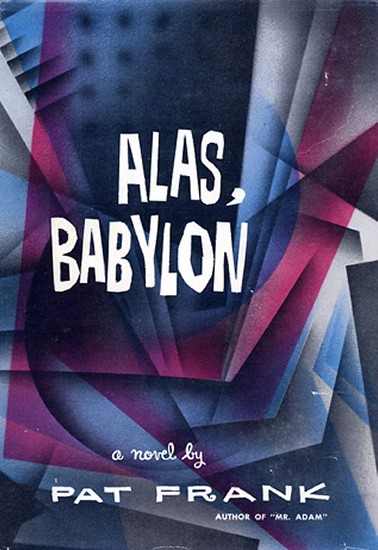

Pat Frank's Alas, Babylon was released just two months ago, and it has already caused a well-deserved stir. It is, quite simply, sublime. With its strong grasp of the technology of the nuclear war machine, its savvy of human interactions in a post-apocalyptic setting, and its unadorned yet somehow gentle depictions of the well-drawn characters, it is a one-sitting page turner.

In brief: Randy Bragg is a dilletante resident of the sleepy resort and fishing town of Fort Repose, Florida. After an abortive flirtation with politics (his defeat attributable to his soft line on segregation), he lives a rather aimless life. His brother, Mark, is a senior intelligence officer at America's missile command center in Cheyenne Mountain. The book opens on December 3, 1959, with the two world Superpowers on the brink of war. Mark warns Randy that war is imminent and sends his family (wife, two children) to live in Fort Repose.

And not a moment too soon. Within six hours of Helen, Ben Franklin, and Peyton's arrival, Florida and the rest of the nation are hit with several bombs, knocking out first communications and then electricity. Within a day, Fort Repose is reduced to a pre-Industrial oasis in a radioactive hell.

Randy quickly becomes the leader of his local group, which includes not just him and his brother's family, but his strong, liberated girlfriend, Elizabeth, her parents, Randy's black gardener and maid, the maid's husband, a young doctor, Dan Gunn, and a retired Admiral, Sam Hazzard. Together, they become the hope of Fort Repose, assuring its shaky survival over the course of the year after the attack.

Pat Frank sets the stage with care and a nail-biting sense of inexorability; the bombs don't fall until page 91, after we have become intimately familiar with most of the book's protagonists. The hurdles that the residents of Fort Repose must overcome are plausible. The solutions are reasonable. The ending is bittersweet, but tinged with a little hope, and perhaps the best that could be expected.

What impresses me the most about this book is its progressive character. There are several strong woman characters (Helen; Elizabeth; Peyton; Randy's ex-girlfriend, Rita; the town telegrapher, Florence; the town librarian, Alice; Missouri, the maid), and the book is a strong indictment of racial prejudice, along with the legal practices stemming therefrom. It is a book about the triumph of human spirit, as exemplified by all of the species' members.

Is that a strong-enough recommendation? Run, don't walk, to your nearest bookstand and get yourself a copy.

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.