by Kaye Dee

As I write, it’s less than a day since the splashdown of Gemini 12 brought NASA’s second manned spaceflight programme to an overwhelmingly successful conclusion, demonstrating that the Space Agency has finally mastered the art of spacewalking. It’s incredible to think that it’s only been 20 months since the first manned Gemini mission was launched, but the packed schedule of ten flights has tested out all the techniques that the space agency needs to advance to its Apollo lunar programme.

Two for the Show

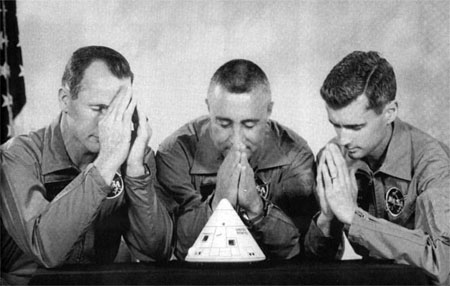

Gemini 12's Command Pilot was former Naval aviator Captain Jim Lovell (left in photo above). Making his second spaceflight, Lovell previously flew on the Gemini 7 long duration mission and now holds the record for the longest time spent in space by any astronaut or cosmonaut. Pilot for this mission was rookie astronaut USAF Major Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, who performed an unprecedented three successful extravehicular activities (EVAs) during this flight. The only member of the astronaut corps to hold a Doctorate, Aldrin is a specialist in rendezvous and docking techniques, and on this mission he put that knowledge to very good use.

A “Halloween” Patch

Gemini 12 was originally scheduled to launch on October 31, so Lovell and Aldrin had considered a Halloween theme for their mission patch. They wanted to evoke Halloween with the use of orange and black colours and also planned to show their Gemini capsule launched on a witch’s broomstick instead of a rocket! However, with the launch rescheduled to November, only the Halloween colour-scheme remained of the original concept.

The final design features the Roman numeral XII at the top of the round patch, in the position it would be on a clock-face. Just like an hour hand, the Gemini spacecraft points to the XII, a reminder that this is the final flight of the Gemini programme. The crescent Moon on the left side of the patch symbolises the ultimate goal of the upcoming Apollo programme.

Training for Weightlessness

Gemini 12's main goal was to complete three EVAs that would demonstrate that NASA had finally cracked the problem of successfully carrying out spacewalking operations, a technique crucial to the Apollo programme.

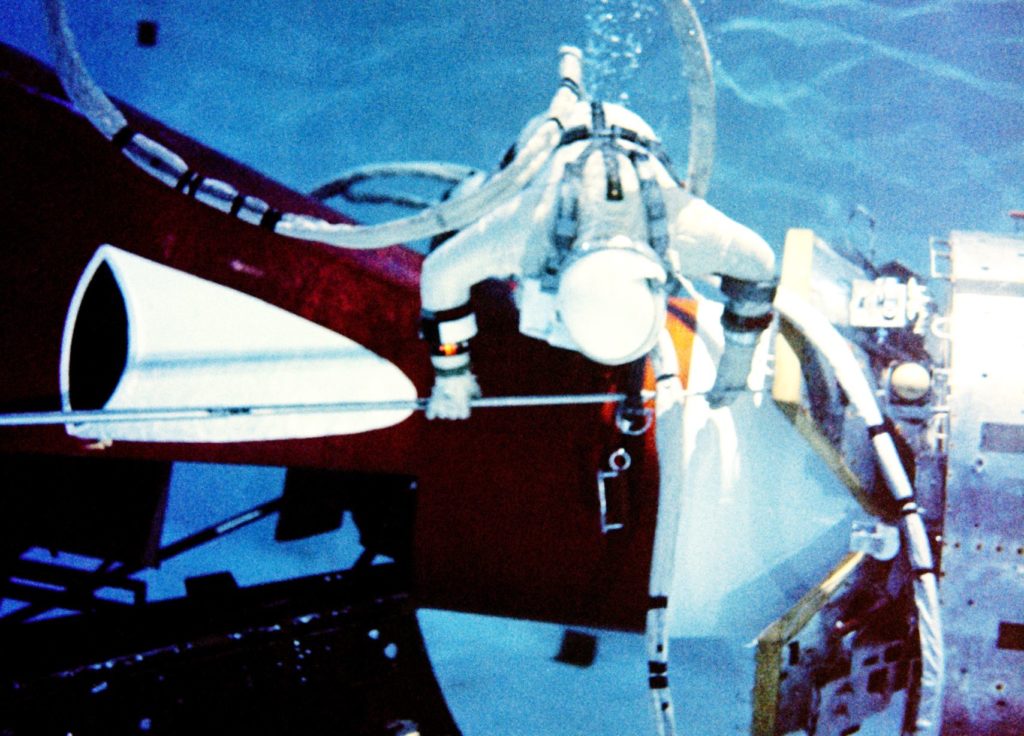

The astronauts who attempted to perform spacewalks on Gemini 9, 10 and 11, had all reported that operating in orbit was much more difficult and tiring than the simulations conducted using the KC-135 weightlessness training aircraft. They also complained that there were few handholds on the exterior of the Gemini and Agena to help them move around in Zero-G. Consequently, a new approach to training was employed for Gemini 12, which I understand was suggested by Astronaut Aldrin himself, who is a keen scuba diver.

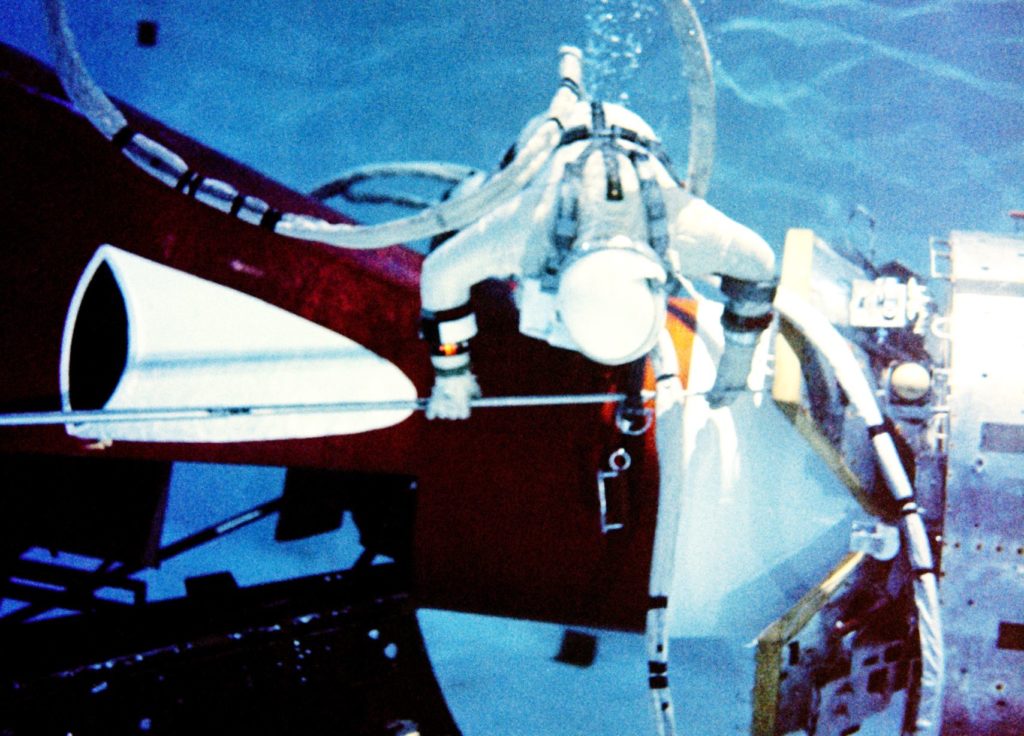

"Buzz" Aldrin practices installing a handrail between the Gemini capsule and Agena target vehicle, in an underwater training simulation

In addition to the KC-135 flights, Aldrin trained in a large pool containing a Gemini mockup. In the pool, special weights were added to the astronaut’s spacesuit to create “neutral buoyancy,” offsetting gravity so he would neither rise nor sink, and Aldrin spent several EVA simulation training sessions of more than two hours underwater.

As well as this new training technique, more handrails and handholds were added to the Gemini capsule, along with a waist tether that would enable Aldrin to turn wrenches and retrieve experiment packages without too much effort.

Dr. Rendezvous Saves the Day, Again!

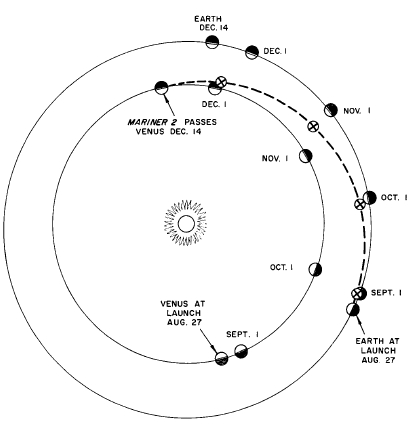

After two delays caused by technical issues, the final Gemini mission lifted off on the afternoon of November 11 US time. On its third orbit, Gemini 12 prepared to dock with the Agena target vehicle, but problems with the Gemini's onboard radar threatened to make that impossible.

Luckily, Aldrin had already developed procedures for onboard backup rendezvous techniques in the event of radar failure. Drawing on his expertise, Aldrin used a sextant and his slide rule, measuring the angle between the horizon and the Agena. Once he had confirmed the information with his rendezvous chart, Aldrin calculated corrections with the spacecraft’s computer, enabling the rendezvous and docking to be successfully accomplished.

Rendezvous with the Sun

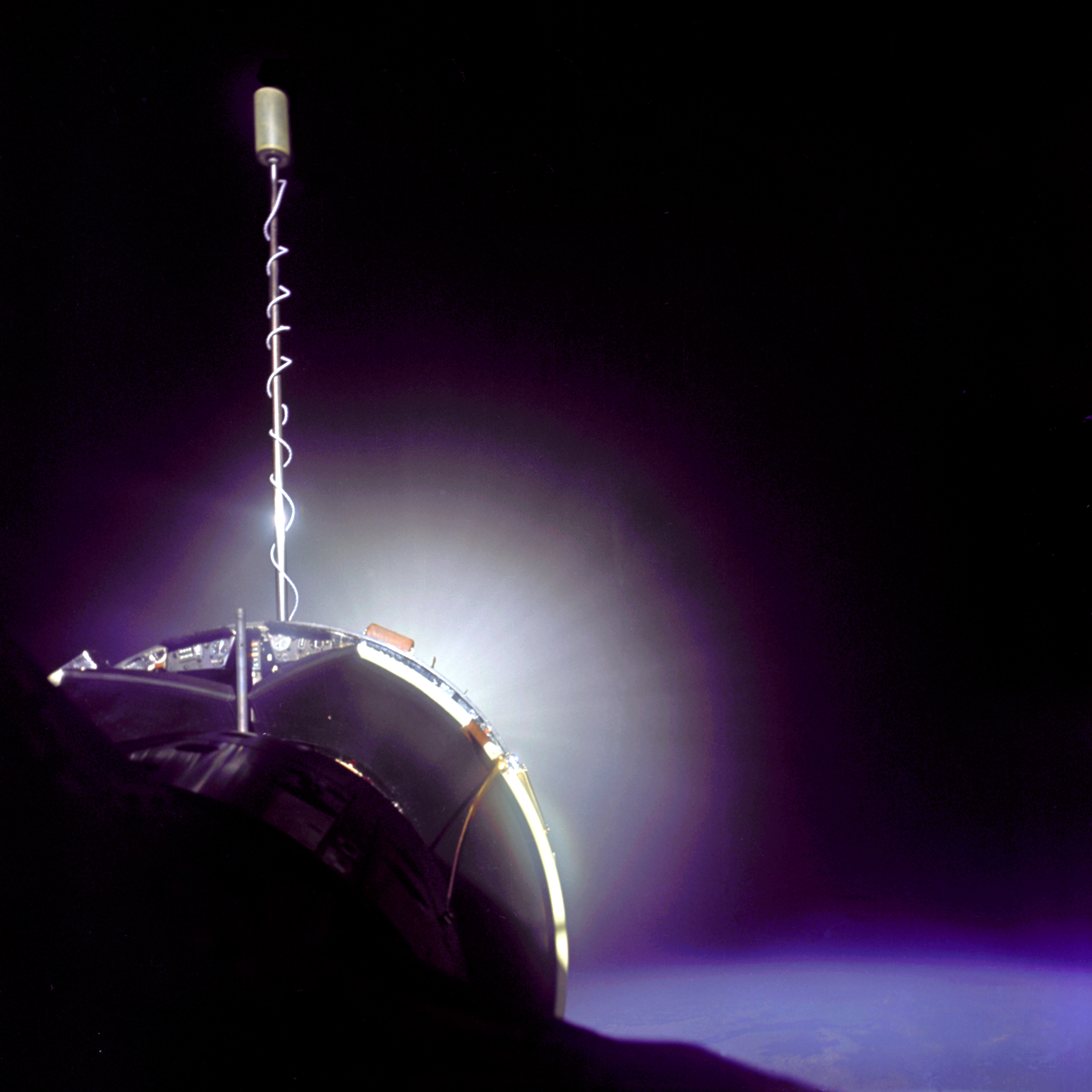

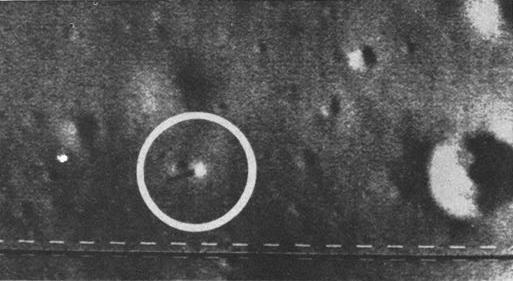

Despite the successful rendezvous, some anomalies with the Agena’s turbopump during launch led to Mission Control cancelling a planned boost to a higher orbit, like that conducted on Gemini 11. Instead, NASA took the opportunity to have the crew photograph a solar eclipse through the spacecraft windows at the beginning of mission day two.

Using the Agena’s secondary propulsion system, Gemini 12 changed orbits to place itself above South America at the right time and location to capture the first colour images of a total solar eclipse free from the interference of the Earth’s atmosphere. During the scant eight seconds that the astronauts could view the eclipse, they snapped four images that are expected to help scientists discover the secrets of the solar corona. The pictures were taken with film sensitive to ultra-violet light, which does not penetrate through the Earth's atmosphere.

Standing Up in Space

About two hours after photographing the eclipse, Aldrin commenced his first EVA, with his head and upper body exposed to space as he stood in the open hatch above his spacecraft seat. During this “stand-up EVA”, which lasted almost two and a half hours, Aldrin took the time to accustom himself to the space environment, which it was thought would better prepare him for his later spacewalk.

One of his first jobs was to install a handrail between his hatch and the docking collar of the Agena that would aid his movements during his day three spacewalk. Aldrin mounted a camera on the side of the spacecraft, with which he took a close-up picture of himself (above), the first shot of its type ever taken! He collected a micrometeorite experiment, and took photographs of the Earth as well as ultra-violet astronomical photography.

Aldrin’s photographic tasks were part of the 14 scientific, medical, and technological experiments planned for Gemini 12. Although five experiments could not be fully completed, those that were included: frog egg growth under zero-g conditions; synoptic terrain and weather photography; airglow horizon photography; and UV astronomy and dim sky photography.

Walking and Working in Space

Gemini 12 flight day three began with some minor fuel cell and manoeuvring thruster issues that would last for the rest of the mission. They did not, however, prevent the highlight of the flight from taking place: a planned two hour tethered spacewalk by Major Aldrin. Until Gemini 12, successfully performing work outside a spacecraft was the one Gemini objective that had eluded NASA, but Aldrin exceeded even the most optimistic hopes for this flight as he performed a record two hours, nine minute and 25 second EVA.

Attached to a 30-foot umbilical cord, Aldrin used the handrail he had installed the day before to assist in attaching a 100-foot long tether between the nose of the Gemini and the Agena. With the handholds, he did not experience the problems Gordon encountered on Gemini 11. Aldrin’s approach to his spacewalk was to go slowly and carefully, resting for two-minute periods between tasks. In fact, about a dozen two-minute rest periods were built into the EVA schedule to prevent Aldrin from becoming exhausted like previous Gemini spacewalkers.

Moving to the spacecraft’s aft adapter, Aldrin supported himself with overshoe restraints and waist tethers to carry out a number of work tasks. He was able to fasten rings and hooks, connect and disconnect electrical and fluid connections, tighten bolts and cut cables. Aldrin then moved across to the Agena, where he worked at pulling apart electrical connectors and putting them together again. He also tried out a torque wrench designed for the Apollo programme.

At the completion of his spacewalk, Aldrin returned to his Gemini seat with no fatigue and all his tasks accomplished. This demonstrated that the use of neutral buoyancy training, available handholds and foot restraints on the spacecraft, and a slow and measured pace of work while in space, are the ingredients needed for future successful EVAs during the Apollo missions.

Going for a Spin

The other major task for flight day three was a repeat of the gravity-gradient stabilisation/artificial gravity experiment performed on Gemini 11. Undocking from the Agena, Gemini 12 moved to the end of the tether connecting the two vehicles and then fired its thrusters to slowly rotate the combined spacecraft. Although they had some difficulty keeping the tether taut, the astronauts were able to use centrifugal force to generate a small amount of gravity during the four hour, 20 minute exercise, and achieve gravity-gradient stabilization. After releasing the tether connected to the Agena, Gemini 12 pulled away from the target vehicle and did not re-dock with it again.

One More Time

The last day of Gemini 12’s mission began with an attempt to sight two yellow clouds of sodium particles ejected by a pair of French Centaure rockets launched from the Algerian Sahara. This experiment was designed to measure high altitude winds. Although Lovell and Aldrin could not see the clouds, they did attempt to photograph them using directional instructions from the ground. We’ll have to wait until those films are developed to see if they were successful.

Shortly afterwards, as the spacecraft came over Australia, Gemini 12’s hatch opened for the final time, and Aldrin conducted a second stand-up EVA. Lasting 55 minutes, this brought Aldrin’s total spacewalking time up to a record five hours and 30 minutes! Most of this EVA occurred as Gemini 12 passed over the night side of the Earth, so that Aldrin could aim his camera at “hot young stars”, which have stimulated the curiosity of astronomers all over the world. He also took numerous ultraviolet photographs of stars and constellations.

Mission Accomplished

After a spaceflight lasting 94 hours, 34 minutes and 31 seconds, Geminin 12 made the second computer-controlled re-entry of the programme, splashing down safely in the western Atlantic just three miles from their target, near the recovery aircraft carrier USS Wasp.

Captain Lovell and Major Aldrin have now been recovered and are on their way back to the United States for post-flight debriefing. But we already know that the Gemini 12 mission has been a fitting grand finale to the Gemini project, clearly demonstrating that NASA has achieved all the goals it set for the programme: it has now mastered rendezvous and docking, direct ascent to orbit rendezvous, long-duration spaceflight equivalent to the time of an Apollo lunar mission, and – the trickiest of all, as they discovered – the art of spacewalking.

We should not forget that Gemini has been a team effort, directly involving more than 25,000 people from NASA, the US Department of Defence, other government agencies, universities and research centres, industry and tracking station partners overseas. Everyone involved should feel great pride in the way spaceflight has been advanced in an amazingly short time.

Very soon, the manned Apollo programme will commence, and we can all hope that it will lead to a successful landing on the Moon before the end of this decade. But we should not forget that its success will stand on the shoulders of the Gemini programme.

Postscript

But where are the Russians in the race to the Moon? No Soviet manned flight has been announced since Voskhod 2 in March last year. Has the USSR withdrawn from the race? That seems unlikely, but why do they appear not to have attempted rendezvous and docking missions? Perhaps they have decided to use a different method of reaching the Moon, such as direct ascent, using a massive multi-stage rocket, without the need for orbital rendezvous? After all, as far as we can tell, they still have larger and more powerful rockets than Western nations. Only time will tell, but I think there are still many surprises in store from the USSR before either the East or West wins the Space Race!

(Want more exciting space stories? Join us for Star Trek tomorrow night at 8:30 PM (Pacific AND Eastern — two showings)!!)

Here's the invitation!

![[June 14, 1967] What's Easy for Two (<i>Venus 4</i> and <i>Mariner 5</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670614mariner-672x372.jpg)

![[May 28, 1967] Around the World in 80 Months (May 1967 Space Roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670528earth-672x372.jpg)

![[April 28, 1967] Tempest in a Teacup (<i>The Terrornauts</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Title-card-672x372.jpg)

![[April 26, 1967] Fallen Cosmonaut ( The Loss of Soyuz 1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Komarov.png)

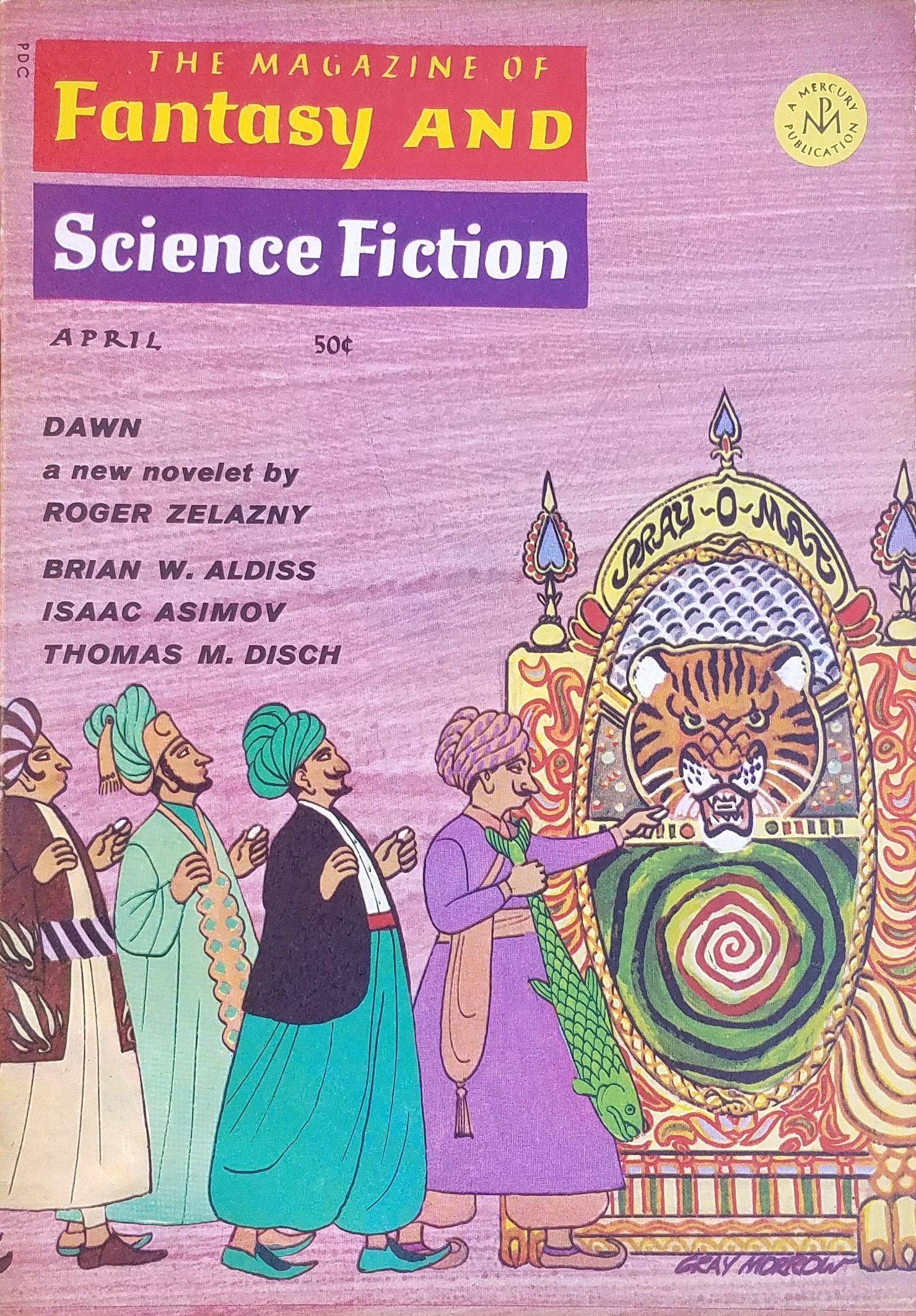

![[March 20, 1967] Vistas near and far (April 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670320cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 28, 1967] "Fire in the cockpit!" (The AS-204 Accident)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Apollo_1-Command_Module-after-fire-465x372.jpg)

![[November 16, 1966] A Grand Finale (Gemini 12)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/G-12-mission-patch-672x372.png)

![[September 18, 1966] Soaring Higher (Gemini 11)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Gemini-11patch-2-308x372.jpg)

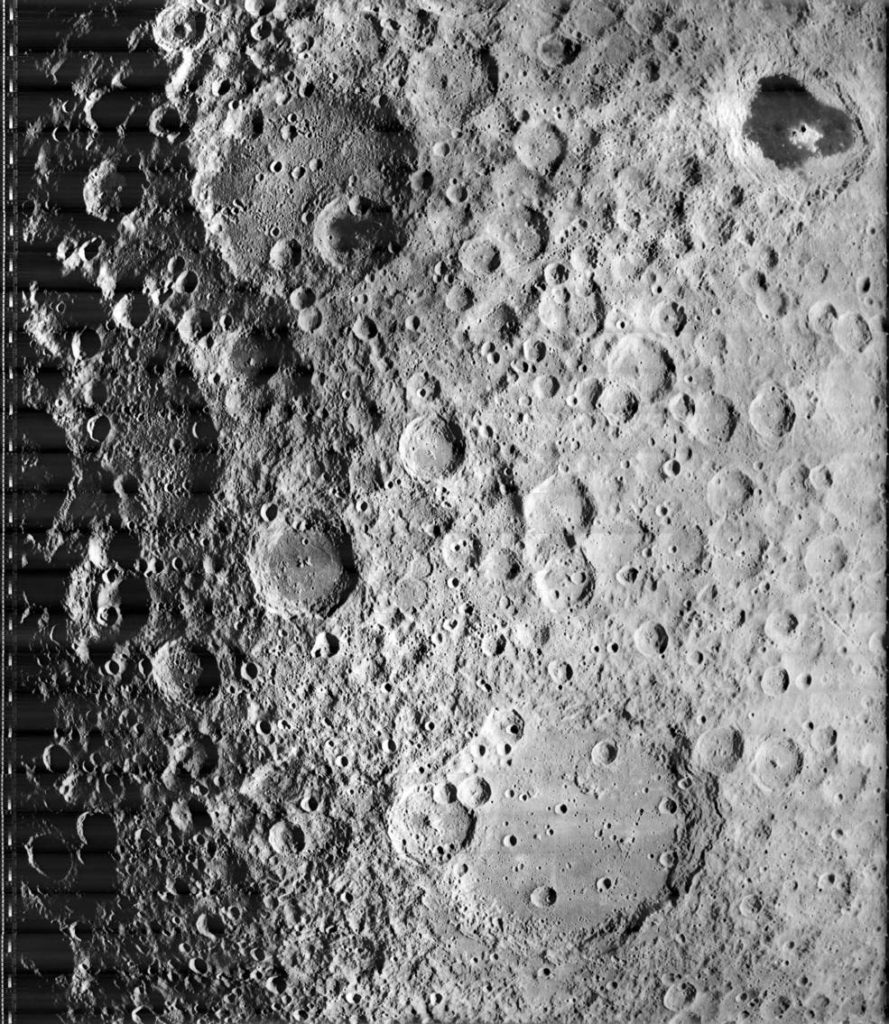

![[August 26, 1966] Shooting the Moon – and Going Even Further (Lunar Orbiter, AS-202 and Pioneer 7)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/lunar_orbiter_1_first_view_of_earth_from_moon-672x372.jpg)