by Gideon Marcus

Bump in road

Here, just a few days after human spaceflight's greatest catastophe, it's easy to begin to doubt. Is this madcap race to the Moon, hanging on a construction leased out to the lowest bidders, all worth it? The cost in money and lives? We've lost six astronauts thus far; Elliot, Bassett and See were all killed in training accidents, but their souls are no less valuable than those of Grissom, White, and Chaffee.

Indeed, the Russians have already announced that they've given up. With the war heating up in Vietnam, with society on Earth not yet Great, should we continue to bother?

The answer, of course, is yes. Any man's death diminisheth me, as John Donne said, but as large as this tragedy looms in our vision now, it will be the smallest of footnotes compared to humanity's epic trek to the stars, which surely must come. It is our species' saving grace that we recover from missteps and proceed more vigorously than ever. And it is out there in the stars that we will find the answers to the riddles of the universe, the exciting frontiers, the possible partners in science and empathy.

Out there

This month's Analog offers a sneak preview of what this far future, when humanity is established in space, will look like..

by Kelly Freas

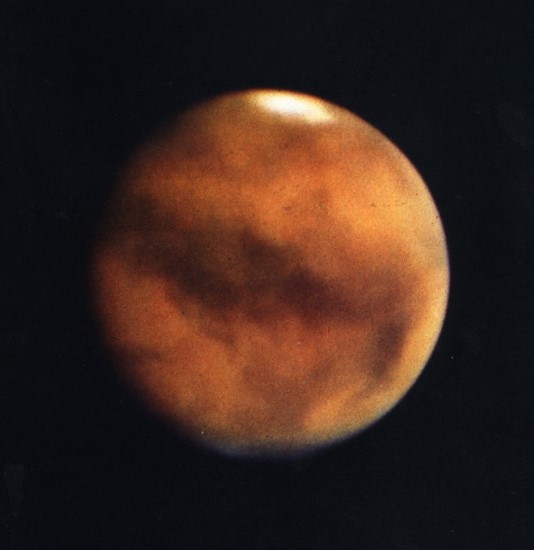

Pioneer Trip, by Joe Poyer

by Kelly Freas

On the first expedition to Mars, an electrical fire causes one member of a three-man crew to succumb to chemical-induced emphysema. His condition, fatal if the ship does not turn 'round (though dubious even if it does) jeopardizes the mission. The commander makes one decision; the stricken crewman another.

I'm not usually a fan of Joe Poyer, who writes as if he gets the same thrill from technical writing as others might from the works sold under the counter and wrapped in brown paper. Nevertheless, this story was pretty affecting–and all the more poignant in light of last week. A solid three star effort.

There Is a Crooked Man, by Jack Wodhams

by Kelly Freas

Science fiction usually explores the positive effects of technology. This mildly droll story deals with how new advances are used for nefarious purposes. Teleportation, brain transplant, mind-blanking frequencies, a precognition drug–these all lead to a race between criminal elements and the police.

Told in a bunch of very short snippets, it's a surprisingly readable, if not tremendous, tale.

Three stars.

The Returning, by J. B. Mitchel

by Leo Summers

A little spore, the only remaining particle of an alien expedition thousands of years old, is awoken by a flash flood through a desert air force proving ground. The creature quickly awakens, eager to make contact with the sender of the modulated signals it is receiving. To its dismay, the alien finds only a weaponized drone, hallmark of a savage society. But the pacifistic being has other uses for the plane…

If J.B. Mitchel be "John Michel", then he is a veteran, indeed. He first started writing in the 1930s, and I don't believe I've seen anything from him since I started the Journey. His skill shows. His prose is evocative, his descriptions vivid. And I very much appreciate a story where the "monster from outer space" is basically a good guy, not bent on Earth's conquest.

Four stars.

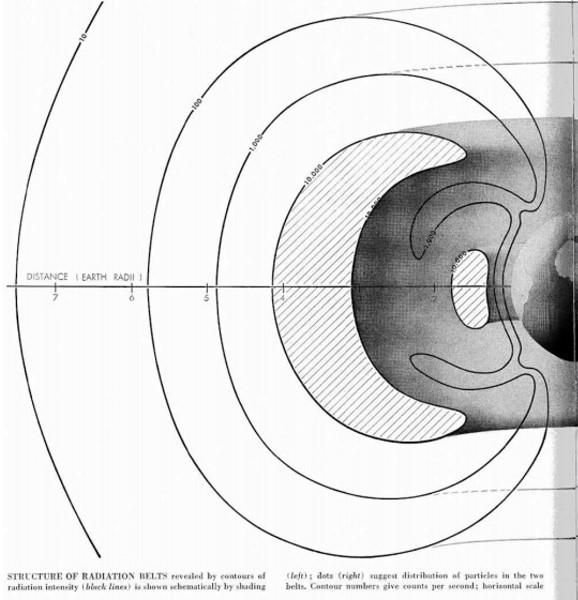

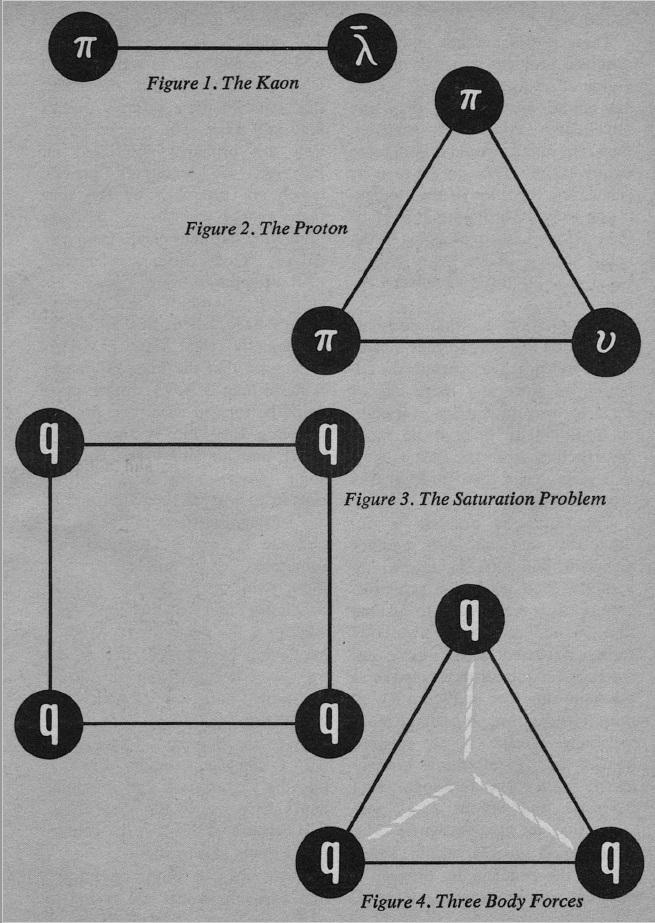

The Quark Story, by Margaret L. Silbar

The one piece by a woman published in any SF magazine this month is this nonfiction article. It's quite good.

Last year, I read a lot of physics books for laymen. The consensus has been that the menagerie of subatomic particles was reminiscent of the zoo of elements discovered by the late 19th Century. There must be some underlying simplicity that results in the multiplicity. For elements, it was electrons, protons, and neutrons. For those and smaller elementary particles, the answer appears to be still smaller bits called "quarks".

It all makes perfect sense the way Ms. Silbar lays it out, even if editor John Campbell is a doubting Thomas about it. The only fault to the article is it could have used another page or two to explain some of the trickier concepts (e.g. Pauli Exclusion Principle).

Four stars.

Amazon Planet (Part 3 of 3), by Mack Reynolds

by Kelly Freas

The final chapter of Mack Reynold's latest turns everything on its head. In the first installment, we followed Guy Thomas, a would-be merchant, to the planet of Amazonia. Said world is reputed to be utterly dominated by women, and men aren't allowed to escape. Upon arriving, it was revealed that Thomas is none other than Ronny Bronston, Section G agent extraordinaire.

Part Two involved Bronston meeting up with a domestic masculine resistance movement, "The Sons of Liberty", several attempts on his life, capture and truth-drug doping by the Amazon government, and copious examples of an almost laughable communistic, female-run despotism. At this point, I had to wonder what the normally sensitive Reynolds was trying to do. His matriarchy was a paper-thin caricature.

Turns out it was all a big put-on, mostly at the instigation of the daughter of one of the world's leaders. Amazonia has long since evolved beyond its primitive beginnings and is actually quite a good example of enlightened equality and meritocracy. The trouble in paradise comes not from within, but without–at the hands of a rogue Section G agent.

Part Three is half adventure story and half political lecture (as opposed to Part One which was all lecture and Part Two, which was mostly adventure). Nevertheless, Reynolds isn't bad at both, and I do appreciate his both subverting expectations and extrapolating an interesting political experiment.

Three stars for this segment, and three and a half for the whole, which is greater than the sum of its parts.

Elementary Mistake, by Winston P. Sanders

by Kelly Freas

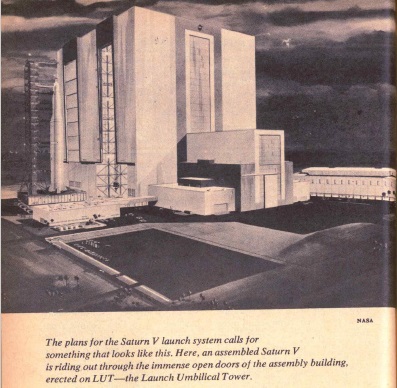

I really liked the setup on this one: there's no faster than light drive, but there are matter transmitters (a la Poul Anderson's story "Door to Anywhere" in Galaxy). So ships are sent out at relatavistic speeds to set up teleporters on distant worlds. The trip takes five or ten or twenty years for outside observers, but the actually crew experience only a matter of months. And so, humanity spreads.

Only on the world of Guinevere, not only are none of the required minerals available to build the transmitter, but the atmosphere itself has an inebriating effect. What's a creative crew to do?

It's a reasonable puzzle story, though I have trouble contemplating a world where calcium doesn't exist but strontium does in quantity. The only thing I took umbrage with was 1) the lack of women on the exploration team, and 2) the explicit implication that the only thing women are good for is servicing men.

Given that this issue has both a great science article by a woman and the conclusion of a serial about a perfectly good planet run by women, this stag story set in the far future is particularly jarring. But Anderson/Sanders has always had a problem with this, which strikes me as strange given that his wife is herself a science fiction writer.

Anyway, three stars.

Leading the pack

Speaking of averages, Analog, which had hitherto been relatively low in the ranks of magazines for several months suddenly emerges as the best of the lot, clocking in at a decent 3.3 stars. That's partly because its competition is rather weak. Only SF Impulse (3.1) finished above water. All the others scored less than three stars: IF (2.9), Fantasy and Science Fiction (2.6), Worlds of Tomorrow (2.5), Galaxy (2.4), and Amazing (2.2).

Analog also, atypically, featured the most women contributors…since none appeared anywhere else! Given that Lieutenant Uhura appears front and center on every episode of Star Trek, I think it's time literary SF caught up with its boob tube sibling.

Or we might end up with a much more lasting disaster!

![[January 31, 1967] The Law of Averages (February 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670131cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 26, 1965] Stag Party (September 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/650828cover-396x372.jpg)

![[Sep. 1, 1963] How to Fail at Writing by not Really Trying (September 1963 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630831cover-672x372.jpg)