by Fiona Moore

An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe

Theatrical poster for An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe

Theatrical poster for An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe

An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe is an hour-long film in which four Edgar Allan Poe stories are recited by Vincent Price. Originally made as a television play (and in a way which suggests it was based on a theatrical production, albeit with the addition of some new visual effects), it’s reminiscent of the BBC’s A Ghost Story For Christmas segment, and I was recently asked to view it as a possible acquisition as a teaching tool by my university’s English Literature department.

The Cask of Amontillado

The programme is split into four segments, in each of which Price recites a different Poe short story. Fairly predictably, these are “The Tell-Tale Heart”, “The Sphinx”, “The Cask of Amontillado” and “The Pit and the Pendulum”. Each segment is performed with Price in character as the narrator of each story, with appropriate costuming and sets. Although Price does show a decent range in playing different characters, they’re all very much within Price’s repertoire as an actor, so, although none of the performances are bad, there are no real surprises to be had here.

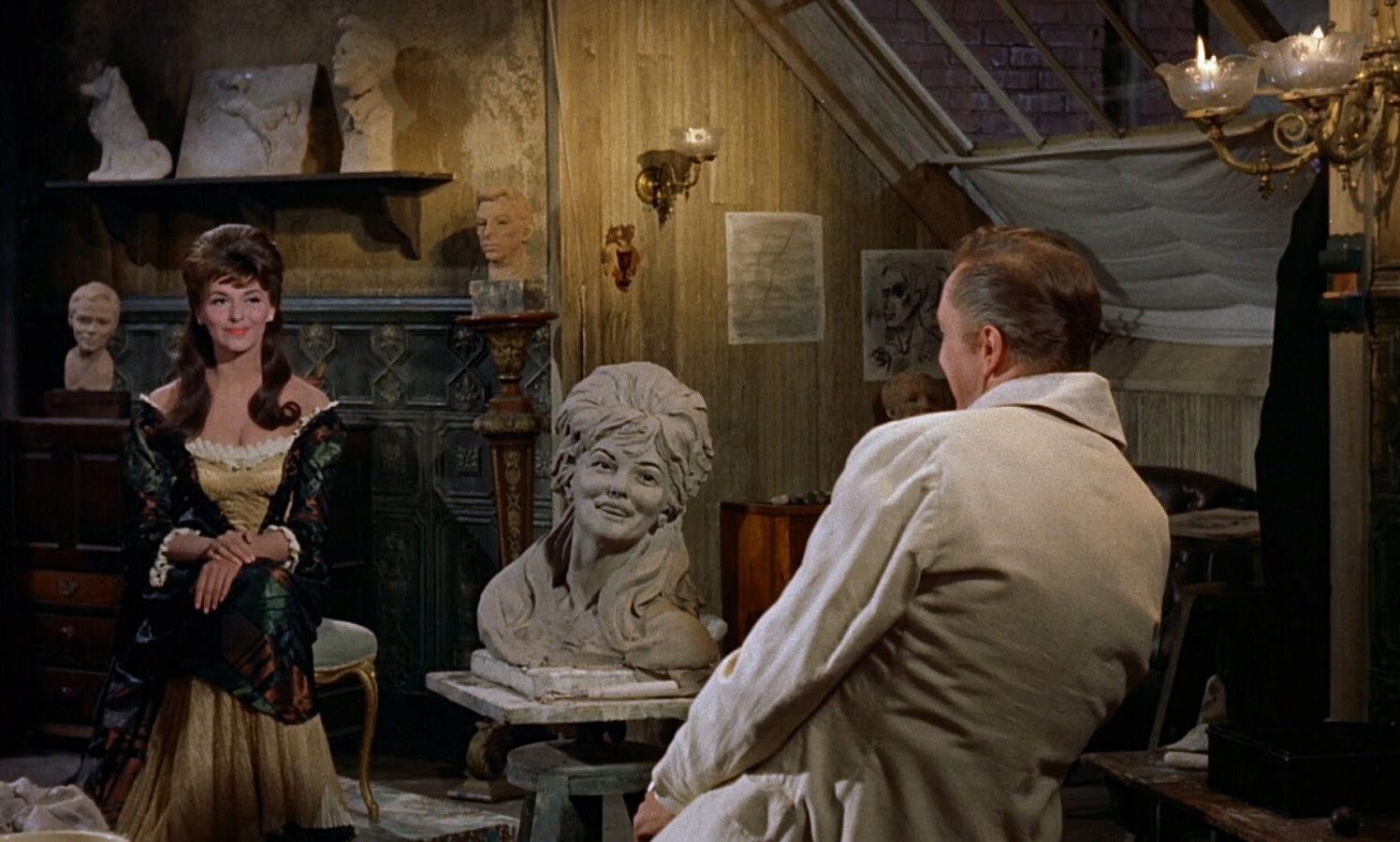

The Sphinx

The Sphinx

I felt the best segment was “The Cask of Amontillado”. Price really seems to relish the role of Montressor and plays him with a wicked twinkle in his eye, surrounded by luxurious draperies and furniture and a banquet-table of food. The weakest for me was “The Sphinx,” which struggled to hold my attention, though it did have an effective use of special effects when we briefly see a skull overlaid over Price’s face at a crucial moment.

The Pit and the Pendulum

The Pit and the Pendulum

By contrast, “The Pit and the Pendulum” was a good enough dramatization of an exciting story, but the problem was that the producer seemed to feel it needed jazzing up with effects shots of Price falling into the pit, Price helpless before the pendulum, Price faced with colour separation overlay ("chroma-key" to yanks) flames, and so forth. The rats were far too cute, with inquisitive little faces and glossy fur, for me to find them horrific.

Finally, “The Tell-Tale Heart” was a good choice as the opening story, told simply with the set a bare garret, with Price steadily ramping up the hysteria as the narrator follows his path into murder and madness.

The Tell-Tale Heart

The Tell-Tale Heart

One great benefit I can see from this production is a chance to show audiences who may just know Poe from the cinematic productions loosely based on his work, just how skilled a horror writer Poe was in real life. The issue with something like “The Pit and the Pendulum” is that one can’t really get an entire 90-minute film out of it without adding a lot of material, which, while it can work as a movie, means you lose the terrifying economy of the original story (although if anyone wants to adapt “The Cask of Amontillado”, I think one could spend at least 90 minutes exploring the buildup of resentment in the two characters’ relationships that led up to the final murder). For this reason, I’m recommending that the English Literature department acquires a copy, and would also say that, if it turns up on TV in your region, it’s worth a watch.

3 out of 5 stars.

by Victoria Silverwolf

There's A Signpost Up Ahead . . .

Two films I caught recently reminded me of Rod Serling's late, lamented television series Twilight Zone. Let's take a look.

Less than half an hour long, this skiing film is the sort of thing that might be shown at a college campus, before the main feature in a movie theater, or to fill up time on television in the wee hours of the morning. The brief running time isn't the only thing that reminds me of Serling's creation.

We begin with scenes of people skiing, edited in a jumpy way. Jazz, rock, and folk music fill up the soundtrack. The skiers also fool around in the snow, eat some fruit, and so forth.

Suddenly, we see a news announcer. He tells us that scientists have determined that every subatomic particle in the universe has reversed polarity. I'm not sure what that means, but let's see what happens.

Somehow, this is supposed to change the way people perceive things. That means the film turns into a negative of itself.

This goes on for a while, then the movie goes back to normal. Once in a while, it turns back into a negative. I guess that's a Moebius Flip. Along with more skiing, we get folks at an amusement park and eating in a restaurant. This part of the film features some pretty impressive and scary scenes of dangerous winter sports. People ski over huge crevasses, wind up on top of a tower of snow, and hang from cliffs.

Is it worth twenty-odd minutes of your time? Well, if you like psychedelic images or are a big fan of skiing, it could be. The science fiction premise is just an excuse to reverse the colors of the film, and there's no real plot at all. I've never been on a pair of skis, so I can only appreciate the athleticism on display here as an outsider.

Two stars.

This is a made-for-TV movie that aired on CBS stations in the USA earlier this month. It begins with five men in World War Two uniforms standing around a wrecked American bomber of the time. They seem to be in pretty good shape, given that they're in a desert wasteland. Things get weird when we find out they've been waiting to be rescued for seventeen years.

The crew of the Home Run.

It quickly becomes clear that they are ghosts, waiting for their bodies to be found so they can stop haunting the wreck.

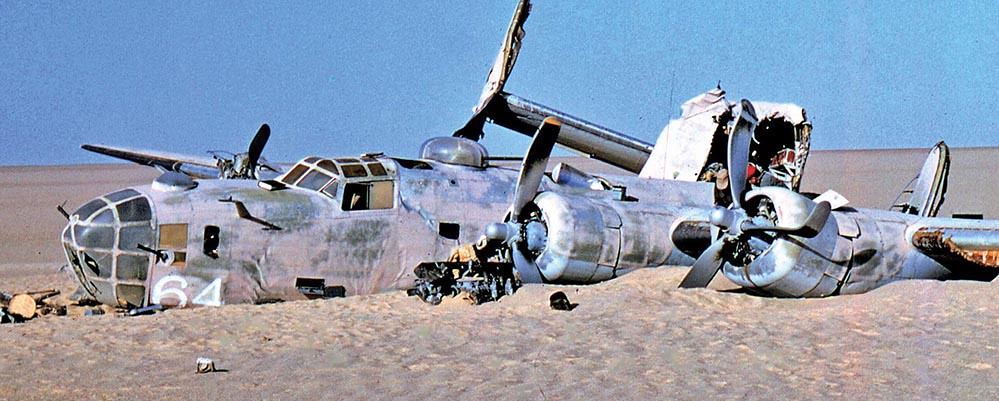

I should note here that the premise is inspired by the case of the Lady Be Good, a bomber that crashed in the Libyan desert in 1943 and was not discovered until 1958.

The real wreck.

Fans of Twilight Zone will remember the episode King Nine Will Not Return, which was also inspired by the fate of the Lady Be Good. That tale goes in a different direction, however.

Two men in an airplane discover the wreck. (By the way, the fact that the ghosts have been waiting for seventeen years means that the movie takes place in 1960 or so. There's no other indication that it's set a decade ago.)

The discoverers, who look more 1970 to me.

This leads to an official investigation by the United States Army. (Remember that the Air Force was part of the Army, and not a separate branch of the service, until a few years after World War Two.) Two officers are in charge of the mission.

William Shatner, fresh from Star Trek, as Lieutenant Colonel Josef Gronke and Vince Edwards, best known as Ben Casey, as Major Michael Devlin.

They pay a visit to the sole survivor of the Home Run. This fellow parachuted out of the plane and landed in the Mediterranean Sea, managing to make it out alive to continue his military career. (More details of what happened later.)

Brigadier General Russell Hamner, as played by Richard Basehart, recently the star of the TV series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea.

Hamner agrees to accompany the two officers to the North African desert. He claims that all of the crew of the Home Run bailed out into the ocean, so the plane must have continued without them for several hundred miles before it crashed. Unlikely, but possible. Flashbacks tell us the real story.

Hamner as the navigator of the Home Run during the war.

The bomber was damaged in an attack by the enemy. The captain ordered Hamner to plot a course back to base, but he panicked and bailed out against orders. Without a navigator, the crew went off course and the plane crashed.

Tension builds as Devlin casts doubt on Hamner's story, and Gronke tells him not to make waves, lest he ruin his career. Both officers have their own concerns about their pasts, adding depth of character. Without giving too much away, let's just say that the truth comes out because of a harmonica, a rubber raft, and Hamner's guilty conscience. There's a powerful and poignant conclusion.

The last ghost faces an eternity playing baseball alone.

This is quite a good movie, particularly for one made for TV. I like the fact that the ghosts appear as ordinary men, rather than being transparent or something. The actors all do a good job. You'll never hear the song Take Me Out To The Ball Game again without having an eerie feeling.

Four stars.

Over the past several years, AIP has adapted stories by H. P. Lovecraft for the big screen—or at least the drive-in. The results have been mixed, but they could certainly be much worse. The first and still the best of these was The Haunted Palace (adapted from The Case of Charles Dexter Ward) back in '63, directed by Roger Corman, with a script by the late Charles Beaumont, and starring an especially tormented Vincent Price. It was a very fine picture. Now we have the latest entry in this "series," The Dunwich Horror, taken from the Lovecraft story of the same name, although it's a pretty loose adaptation.

The Dunwich Horror

One warning I want to give about this movie, one which has nothing to do with sex or violence, is that, aside from being generally a pretty strange film, there are several scenes featuring flashing lights, or a color filter changing rapidly to give one the impression of a strobing light. Some people (thankfully not many) are susceptible to epileptic fits if subjected to such stimuli.

Now, as for the film itself, once we get past what I was surprised to find is an animated (as in a cartoon) opening credits sequence, we start with what seems to be a flashback of a woman giving birth, surrounded by two elderly sisters and an old man. We then flash forward to Miskatonic University, that college of the occult and Lovecraft's making, in Arkham. Nancy Wagner (Sandra Dee) is a student who, in the college's library, meets a good-looking but unusual young man named Wilbur Whateley (Dean Stockwell), who is terribly interested in the Necronomicon. I'm sure his interest in the accursed book and his strange deadpan way of talking are perfectly innocuous. A certain professor at Miskatonic, Henry Armitage (Ed Begley), gets a bit of a hunch that Wilbur is up to no good, but for now does nothing about it.

"The Dunwich Horror" is one of Lovecraft's most celebrated stories, but it's also one of his trickiest. As with "the Call of Cthulhu," Lovecraft wrote "The Dunwich Horror" as if it were a report or an essay, a work of journalism or academia, rather than a fiction narrative. There's no protagonist, properly speaking, although Wilbur is certainly the story's nucleus. This remains sort of the case with the film, although Nancy and Armitage now serve as our eyes and ears, or rather as normal people in what becomes an extraordinary situation. However, it's not Sandra Dee or Ed Begley who caught my attention, but Dean Stockwell as Wilbur, who gives almost what could be considered a star-making role (to my knowledge his most high-profile roles up to now were film adaptations of Sons and Lovers and Long Day's Journey into Night), if not for the movie that surrounds him. Unlike his short story counterpart Wilbur here is not physically deformed, but instead talks in a strangely deadened tone, as if human emotions are foreign to him. Stockwell as Wilbur manages to be uncanny simply through how he talks and acts, which is a major point of praise.

Director Daniel Haller and his team of screenwriters have opted to streamline Lovecraft's story while giving it a sort of romance plot, as well as a dose of sex and violence. Sex and Lovecraft have always been uneasy bedfellows, even in something like "The Shadow Over Innsmouth" which explicitly involves sex in its plot. Wilbur is one of two twins, the other having supposedly died in childbirth, with the father being unknown, and his mother having been kept in an asylum for the past two decades. Wilbur lives with his grandfather, Old Man Whateley (Sam Jaffe, who some may recognize as that one scientist in the now-classic The Day the Earth Stood Still), who seems convinced his grandson is also up to no good, but arbitrarily (the film does nothing to explain this) does nothing about Wilbur being a scoundrel. For his part, Wilbur sees Nancy as a pretty fine girl—for a dark ritual, that is. The idea is that if he can steal the Necronomicon and impregnate Nancy (the implication, via a mind-bending scene, is that he rapes her), he can bring one of "the Old Ones" into the human world.

As this point the plot splits in two, with one half focusing on Wilbur and Nancy's "romance" while the other sees Armitage tracking down the mystery of Wilbur's birth, since it becomes apparent the young man and the Necronomicon are somehow connected. One of the strangest (sorry, "far-out") scenes in the whole movie is when Armitage goes to see Wilbur's mother (Joanne Moore Jordan), who apparently had lost her mind many years ago upon giving birth to Wilbur and his dead twin. When it comes to this movie, there are two types of strange: that of the unnerving sort, and that of the cheesy sort. There are parts (sometimes moments within a single scene) of this movie that do a good job of spooking the audience, and others where it's rather silly. With that said, the nightmarish effect of Jordan's performance combined with the changing color tints in this scene make it one of the most effective. This is a movie that generally shines brightest when it focuses on Stockwell's performance and/or the Gothic cliches (including a creepy old house) that clearly also influenced Lovecraft's writing. Maybe it's because they didn't have the budget for it, but the lack of an on-screen monster for the vast majority of the film's runtime also works in its favor.

When Old Man Whateley finally decides to take action, Wilbur kills him for his troubles, along with imprisoning one of Nancy's friends and turning her into some kind of abomination. Meanwhile Wilbur gives his grandfather a heathen burial and in so doing provokes the wrath of the Dunwich townspeople, who never liked the Whateleys anyway. It's revealed, or rather speculated, that Wilbur's twin may not have died after all, but instead gone to the realm of the Old Ones while Wilbur got stuck on Earth as a human. Armitage and the townsfolk succeed in stopping Wilbur from completing his ritual with the unconscious Nancy, Armitage being well-versed enough in the Necronomicon to use the book against Wilbur, killing him with a blast of lightning. So the last of the Whateley men is dead. Unfortunately, the final shot, eerily showing a fetus growing inside Nancy (which is odd, because she's probably only been pregnant a day or two), implying an Old One may be born after all.

Lovecraft purists will surely be much disappointed with this movie, and even as someone who is not exactly a Lovecraft fan, I have to admit it's by no means perfect. Even at 90 minutes it feels a bit overlong, and it tries desperately to contort one of Lovecraft's more unconventional stories into having a three-act structure. I also get the impression that the addition of blood and breasts was to appease those (people my age and younger) who are suckers for AIP schlock. Not too long ago we had Roger Corman's so-called Poe cycle, which for the most part did Edgar Allan Poe's (and in one case Lovecraft's) fiction justice on modest budgets. I would say The Dunwich Horror is on par with one of the lesser of Corman's Poe movies.

A high three stars.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!

![[January 28, 1970] Cinemascope: Just a Poe Boy (<em>An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe</em>, <em>The Moebius Flip</em>, </em>Sole Survivor</em>, and <em>The Dunwich Horror</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/12970-an-evening-of-edgar-allan-poe-0-460-0-690-crop-2830000383-460x372.jpg)

![[May 22, 1968] Finding a New Way: <i>Witchfinder General</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680522poster-672x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1964] Death Has No Master (Roger Corman's <i>The Masque of the Red Death</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/masqueposter-672x372.jpg)

![[March 19, 1964] When Vampires Rule the World (Ubaldo Ragona and Sidney Salkow's <i>The Last Man on Earth</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640319lastmanposter-672x372.jpg)