I've devoted much ink to lambasting Astounding/Analog editor John Campbell for his attempts to revitalize his magazine, but I've not yet actually talked about the latest (February 1960) issue. Does it continue the digest's trend towards general lousiness?

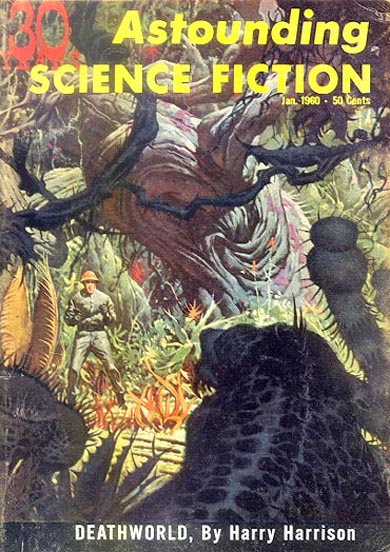

For the most part, yes. Harry Harrison's serial, Deathworld, continues to be excellent (and it will be the subject of its own article next month). But the rest is uninspired stuff. Take the lead story, What the Left Hand was Doing by "Darrell T. Langart" (an anagram of the author's real name—three guess as to who it really is, and the first two don't count). It's an inoffensive but completely forgettable story about psionic secret agent, who is sent to China to rescue an American physicist from the clutches of the Communists.

Then there's Mack Reynold's Summit, in which it is revealed that the two Superpowers cynically wage a Cold War primarily to maintain their domestic economies. A decent-enough message, but there is not enough development to leave much of an impact, and the "kicker" ending isn't much of one.

Algis Budrys has a sequel to his last post-Apocalyptic Atlantis-set story called Due Process. I like Budrys, but this series, which was not great to begin with, has gone downhill. It is another "one savvy man can pull political strings to make the world dance to his bidding" stories, and it's as smug as one might imagine.

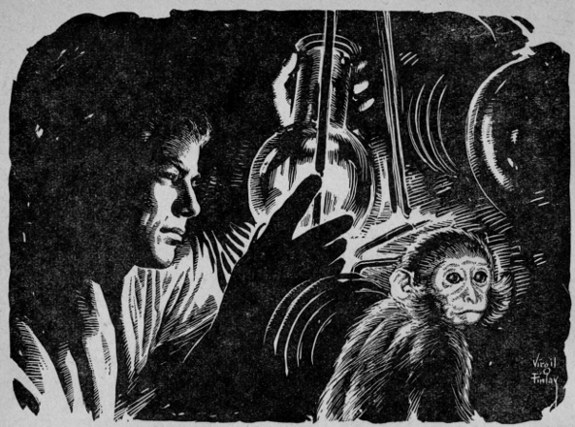

The Calibrated Alligator, by Calvin Knox (Robert Silverberg) is another sequel featuring the zany antics of the scientist crew of Lunar Base #3. In the first installment in this series, they built an artificial cow to make milk and liver. Now, they are force-growing a pet alligator to prodigious size. The ostensible purpose is to feed a hungry world with quickly maturing iguanas, but the actual motivation is to allow one of the young scientists to keep a beloved, smuggled pet. The first story was fun, and and this one is similarly fluffy and pleasant.

I'll skip over Campbell's treatise on color photography since it is dull as dirt. The editor would have been better served publishing any of his homemade nudes that I've heard so much about. That brings us to Murray Leinster's The Leader. It is difficult for me to malign the fellow with perhaps the strongest claim to the title "Dean of American Science Fiction," particularly when he has so many inarguable classics to his name, but this story does not approach the bar that Leinster himself has set. It's another story with psionic underpinnings (in Astounding! Shock!) about a dictator who uses his powers to entrance his populace. It is told in a series of written correspondence, and only force of will enabled me to complete the tale. There was a nice set of paragraphs, however, on the notion that telepathy and precognition are really a form of psychokinesis.

I tend to skip P. Schuyler Miller's book column, but I found his analysis of the likely choices for this (last) year's Hugo awards to be rewarding. They've apparently expanded the scope of the film Hugo from including just movies to also encompassing television shows and stage productions, 1958's crop being so unimpressive as to yield no winners.

My money's on The World, The Flesh, and The Devil.

—

Galactic Journey is now a proud member of a constellation of interesting columns. While you're waiting for me to publish my next article, why not give one of them a read!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.