by Gideon Marcus

Up and over

Just as America returned to space in a big way with this month's flight of Apollo 7, the Soviets have also recovered from their 1967 tragedy (Soyuz 1) with an impressive feat. Georgy Beregovoi, a rookie cosmonaut (ironically also the oldest man in space thus far, surpassing 45 year-old Wally Schirra by two years) has taken Soyuz 3 into orbit for a series of rendezvous and perhaps dockings (TASS is being vague on the issue) with the unmanned Soyuz 2.

Comrade Beregovoi in training

We've seen flights like this before, but this is the first time there has been a person involved. Many are calling this a harbinger of an impending lunar flight, though NASA is adamant that this particular flight won't go to the moon. Indeed, Dr. Ed Welsh, Secretary of the National Aeronautics and Space Council says Soyuz and September's Zond 5, which went around the moon, are completely different craft and the Russians aren't even close to fielding a lunar mission.

We'll have more on this flight in a few days. Stay tuned.

On the ground

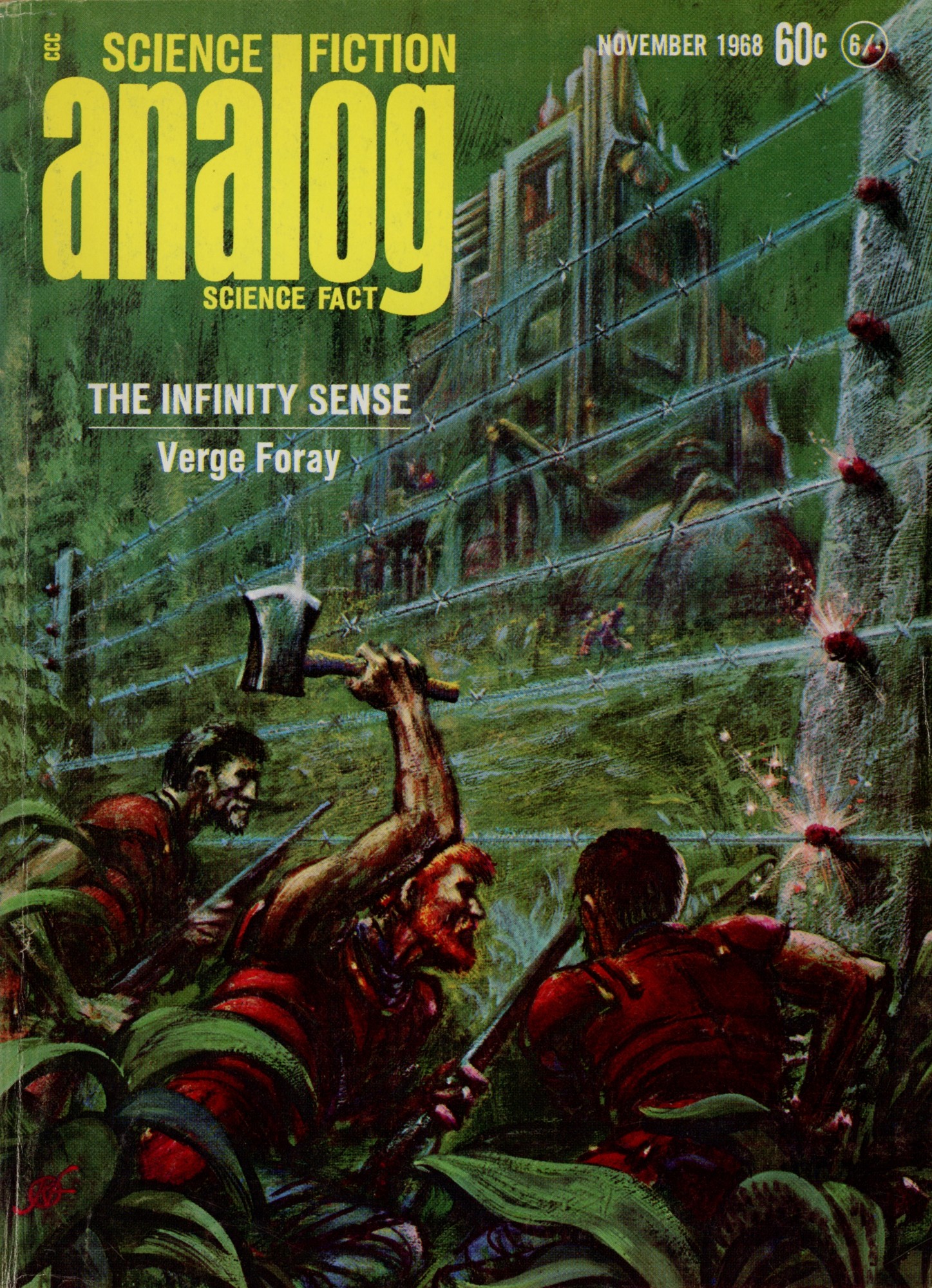

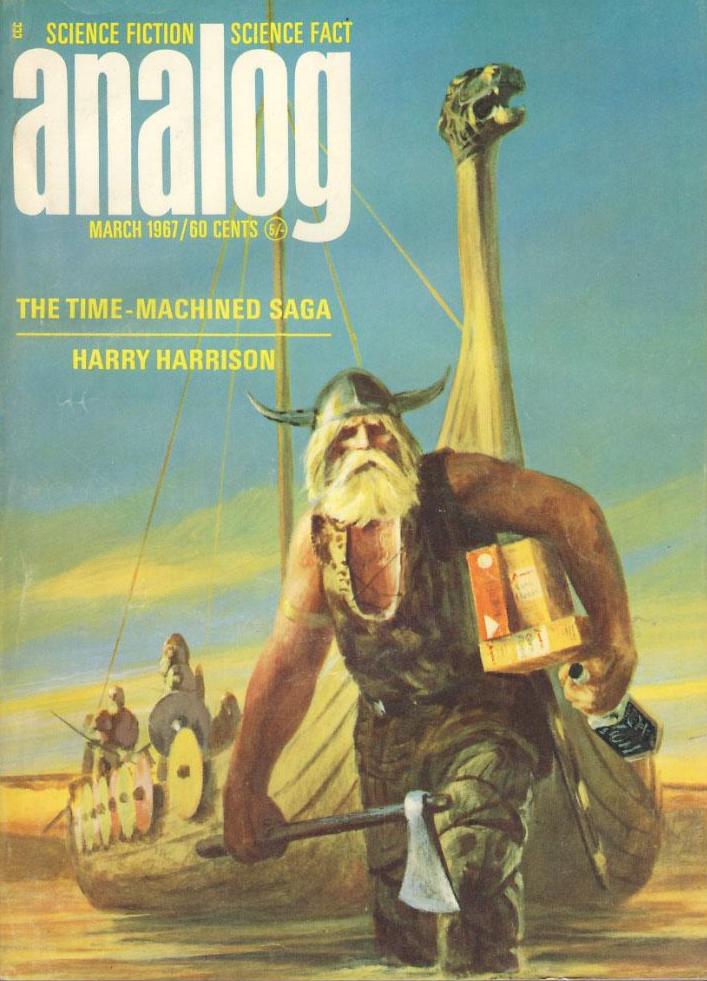

Like the flights of Soyuz 2 and 3, this month's Analog is outwardly impressive, but once you dig in, it's not so great.

by Kelly Freas

The Infinity Sense, by Verge Foray

by Kelly Freas

Centuries from now, after the fall of the Age of Science, humanity is divided into two camps: the "Olsaparns", who dwell in isolated technological camps and retain a semblance of the original technology and society, and the Novos—psionically adept savages who live in conservative Packs. One of the Pack members is Starn, who possesses a brand new ability that allows him to best even the telepathically and premonitionally blessed. He runs afoul of Nagister Nont, a highly adept, highly disagreeable trader, who kidnaps his wife.

After a raid on the Olsaparns leaves Starn close to death, the technologists remake him into something more machine than man, like Ted White's Android Avenger. The Olsaparns want Nont out of the picture, so they help Starn in his quest to defeat the mutant and get back his wife.

I have no fault with the writing, which is brisk and engaging. I take some issue with the pages of discussion on whether or not psi powers be linked with primitiveness, or the concept that humanity could regress to Pithecanthropy in a scant few generations (or the idea that evolution must be a road that one goes forward and backward on; I thought we gave up teleology last century). But I blazed through the novella in short order, so… four stars.

The Ultimate Danger, by W. Macfarlane

by Kelly Freas

In which Captain Lew Frizel takes a shipload of eggheads to a hallucinogenic planet. He is the only one who, more or less, keeps his head. The message appears to be that LSD can be employed by aliens to judge our character. Or something.

Three stars?

The Shots Felt 'Round the World, by Edward C. Walterscheid

This piece, on atomic tests, was much easier reading than Walterscheid's last article. Do you realize that we have detonated half a billion TNT tons worth of nuclear explosives since 1945? It's a wonder there's anything left of Nevada.

Four stars.

The Rites of Man, by John T. Phillifent

by Rudolph Palais

A scientist is working on rationalizing the art of interpersonal relations (because in Phillifent's universe, no one has invented sociology). About twenty pages into that effort, humanoid (really, human) aliens show up and ask to be allowed to compete in the Olympics. They do, but they lose on purpose so we won't hate them. Then we interbreed.

Possibly the dullest, most pointless story I've ever read in this magazine. One star.

The Alien Enemy, by Michael Karageorge

by Leo Summers

Humanity is a resilient creature, tough enough to tame any world. Except that planet Sibylla, with its poisonous soil, extreme axial tilt, thin atmosphere, temperature extremes, high gravity, and violent weather may actually be more than Terrans can handle. What does one do when a world is too minimal to sustain a colony? And what is the value of 10,000 settler lives against the teeming, impoverished billions of Earth?

This is a vividly written piece with some excellent astronomy. If I didn't know better, I'd say Poul Anderson is writing under a pseudonym. I felt the solution to the colonists' problem, though reasonable, was not sufficiently set up to be deduced. Also, I felt Karageorge missed the opportunity to make a more profound statement at the end than "well, humanity can lick almost all comers." I'd have preferred something on the point of colonization or the shifting of priorities on a racial scale.

Still, a high three stars.

Split Personality, by Jack Wodhams

by Kelly Freas

Mauger, a homicidal brute, agrees to be split in two for science instead of getting the chair. Instead of this resulting in two new individuals, it turns out that the two halves remain connected, the gestalt whole. Thus, Maugam can literally be in two places at once.

This is timely as the first interstellar drive has had teething troubles. Two test ships have gotten lost, unable to communicate with Earth. Now, half of Maugam can fly on the ship while the other stays home and reports, since telepathy, for some reason, is instant.

It's actually not a bad story, though it's really just a bunch of magic and coincidence. It works because Wodhams has set it up to work a certain way, not because this is any kind of realistic scientific extrapolation. Also, it's hard to work up any sympathy for a homicidal brute.

Three stars.

Doing the math

When everything is crunched together, we end up with Analog clocking in at exactly 3 stars—again, adequate, but vaguely disappointing. On the other hand, it's been something of a banner month in SF (provided you're not looking for female writers; they wrote less than 7% of the new fiction pieces published). Except for IF (2.6), every other outlet scored higher than 3. To wit:

New Worlds (3.1), Amazing (3.2), New Writings 13 (3.3), Fantasy and Science Fiction (3.4), and Galaxy (3.9).

The stuff worth reading (4/5 stars) would fill a whopping three magazines. Who says the science fiction magazine age is over?

![[October 28, 1968] Impressive at first glance… (November 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681028cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 28, 1967] The Big Stall (March 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670228cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 26, 1965] Stag Party (September 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/650828cover-396x372.jpg)