by Victoria Lucas

No.

No, no, no, no. no. I don’t believe it, can’t believe it, am not going to believe it.

Paul McCartney

Longer than the road that stretches Out ahead."

Continue reading [May 24, 1970] Let It Be (The Beatles break up)

by Victoria Lucas

No.

No, no, no, no. no. I don’t believe it, can’t believe it, am not going to believe it.

Paul McCartney

Continue reading [May 24, 1970] Let It Be (The Beatles break up)

KGJ Weekly News is back! Come watch and find our what happened this week

by Gideon Marcus

A small pond

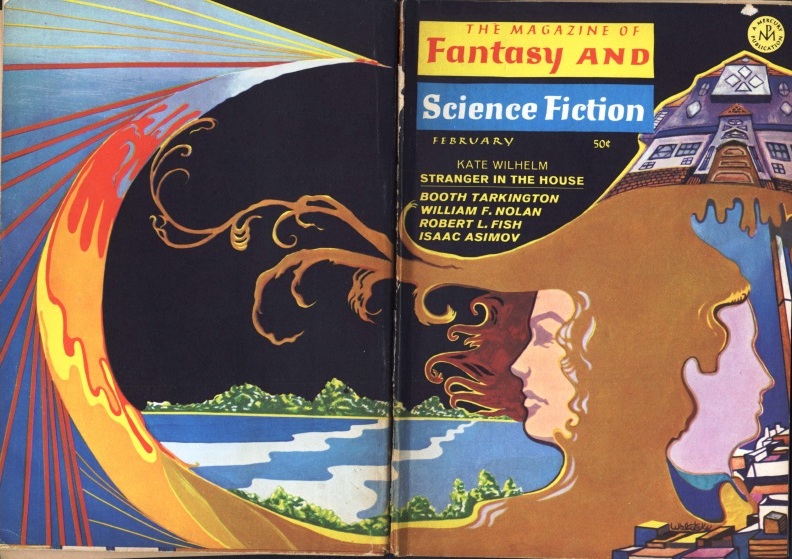

We have exciting tidbits from both sides of The Pond today, so stay tuned for both. But first up, the latest issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

I got a letter from Ted White the other day. Seems he's no longer assistant editor over at F&SF, which is a shame. Apparently, he was once under consideration for editor at Fantastic (and possibly Amazing) back when Celle Goldsmith (Lalli) left! Boy, would that have been an interesting tenure–certainly more interesting than what we got under Sol Cohen.

Anyway, keep reading, because this isn't the only time Ted's name will come up.

by Ronald Walotsky

The Colonies

Stranger in the House, by Kate Wilhelm

We've been seeing a lot more of Kate Wilhelm, lately, which is generally a good thing. Stranger seems as if it will be a fairly typical, if sinister, haunted house story. A middle-aged couple moves into a house in the country, a surprisingly good deal, to escape the hustle and bustle of the city after the husband suffers a heart attack. Immediately, the wife begins to suffer fainting spells and strange visions. A little research uncovers that, since 1920, the place has seen an inordinate number of deaths and inexplicable illnesses amongst its ocuppants.

Is it a vengeful spook? Radon poisoning? Actually, as we quickly learn, it's an alien in the basement. Not just any alien: this one was sent on a first contact expedition. The hope of its race was that they would get to see that transient moment when a species first makes the jump into space.

The problem is, said aliens are hideous, live in a toxic atmosphere, shed acid, and communicate via a telepathy that is about as conducive to human communication as an icepick in the forehead. How, then, can there be a meeting of the minds?

I love a good "first contact" story, and I appreciate that Wilhelm has created a truly alien being. What keeps this piece from excellence are a couple of factors. For one, it is overlong for what it does. More importantly, much of the story, particularly that told from the alien's point of view, is detached and told in past tense. This lack of immediacy in a story that deals with turbulent emotions puts a muffling gauze over the proceedings. I wonder, in fact, if the whole story might have been improved by only including the human viewpoint.

Three stars.

The Lucky People, by Albert E. Cowdrey

Why stay hitched to three channels on the boob tube when you can watch the cannabalistic mutants that prey on your neighbors from the comfort of your own picture window?

Notable for being the first mention of Star Trek I've seen in print science fiction, it is a cute but frivolous tale.

Three stars.

The Stars Know, by Mose Mallette

A young ad exec, graduate of Dr. Ferthumlunger's 40-week handwriting analysis course, is convinced that his boss, the comely Lorna D., is in love with him. How else to explain "the sex-latent capitals, the rounded n's and m's, the generous o's and a's, and the unmistakably yearning ascenders in late."

Never mind that the note which our hero has examined is an angry exhortation to get his work done on time.

The misunderstanding continues, with Lorna actually becoming infatuated with the exec, but said exec steadfastedly refuses to believe it, analysis of subsequent notes revealing (so he believes) that she isn't interested at all. Of course, he doesn't actually read the contents of the notes. He only looks at the handwriting.

What seems a silly story at first is actually, upon further analysis, an indictment of those who miss the forest for the trees: the mystics, numerologists, saucer enthusiasts, and what have you, who ignore the evidence and invent their own patterns to reinforce their beliefs. It's really quite brilliant satire!

Or…perhaps I'm reading too much meaning into the thing.

Three stars.

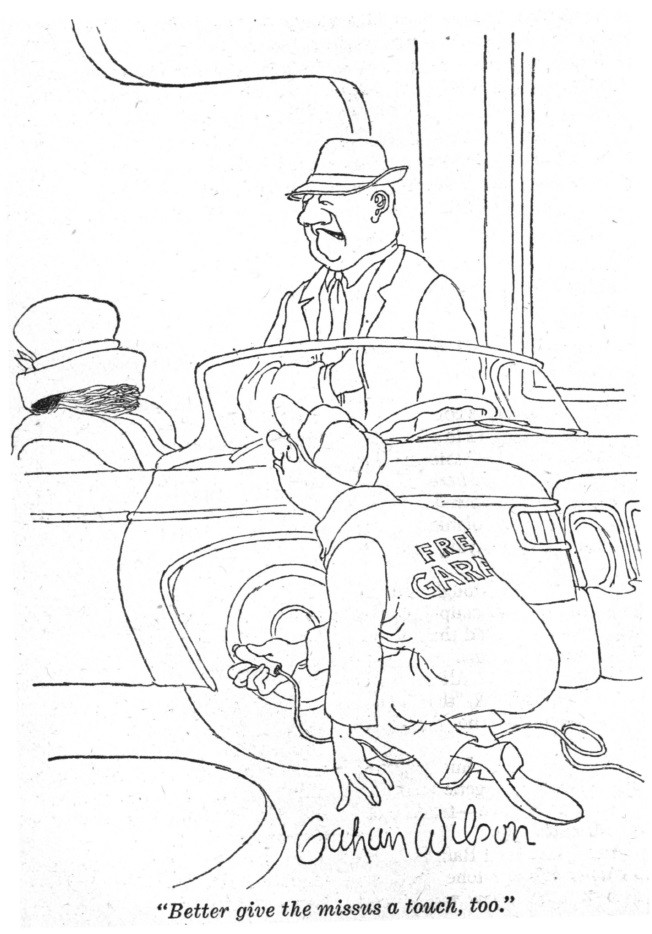

by Gahan Wilson

Aperture in the Sky, by Theodore L. Thomas

Thomas' essays are usually not worth the single page they are written on. This time, however, he's hit on a good'n: artificial satellites designed to occult radio sources for better measurement of their distance. It sounds rather brilliant to me.

Four stars.

From a Terran Travel Folder, by Walter H. Kerr

Less successful is this one page program, I think advising aliens on the joy of eating people. I read it a few times and did not find myself enjoying it.

Two stars.

He Kilt It with a Stick, by William F. Nolan

Then we hit the nadir of the issue. The author of Logan's Run offers up a tale of a man who hates cats and does horrible things to them until they get their inevitable, macabre revenge.

Not only is this story cliché in the extreme, but if I never read another account of cruelty to cats, it'll be too soon.

One star. For shame.

Wednesday, Noon, by Ted White

Quality returns with this short piece by Ted White. When the rapture comes, the music may not be heavenly in origin, but it'll be compelling, all the same. This story took a whopping three and a half years to be printed from the date of submission (latter 1964), but I'm glad it finally made it. White has a real knack for living in his characters, conveying their sensory experience and internal monologues with visceral effectiveness. Wilhelm's piece could have used his touch, I think.

It helps that White lives in New York, the setting of the story, and lived through that brutal summer when Martha Reeves' classic first hit the airwaves…

Four stars.

The Locator, by Robert Lory

Gerald Bufus, accountant, is meticulous to the extreme. He also has a hobby: tracking the visitations of flying saucers to ensure he can one day be present at a landing. Sadly, his overwhelming addiction to symmetry compells him to greet the alien ship at the exact center of their predicted arrival site.

Three stars.

I Have My Vigil, by Harry Harrison

The three human crewmembers of the first interstellar flight go mad in hyperspace, and presently, none are left alive aboard the vessel except the one robot steward, who mechanically goes through the motions of serving the dead humans.

The twist at the end is ambiguous: has the robot also gone insane? Or is he actually a fourth crewmember, who has retreated behind a fictional metal shell in his own kind of insanity?

Four stars.

To Hell with the Odds, by Robert L. Fish

I love "deal with the Devil" stories, and this one, about a washed-up golfer who bargains to win this year's Open, is great all the way up to the end…where it flubs the finish. The problem I have is the clumsy phrasing of his final wish (an attempt to get out of the deal, which of course backfires,) given that he had 18 holes to perfect it.

Three stars.

The Predicted Metal, by Isaac Asimov

The Good Doctor continues his series on the discovery of metals, this time recounting the creation of the Periodic Table. It's a fine piece, but I feel as if it was recycled from his 1962 book, The Search for the Elements.

Four stars.

The Veiled Feminists of Atlantis, by Booth Tarkington

The last is a 40-year old piece. Two scholars meet to discuss a legend of Atlantis in which the women not only win equality, but then fight a cataclysmic war with Atlantean men for the right to retain the distinction of their femininity–the veil.

Tarkington wrote the piece to poke a bit of fun at the war between the sexes that was waging in the 20s, whereby women had the temerity not only to demand the vote, but also to engage in male or female fashion and hobbies as they chose, and men were affronted by their cheek.

Interesting as an artifact, I suppose. Three stars.

Summing up

All in all, a decent but not outstanding magazine this month. And now onto something in an entirely different vein…

by Fiona Moore

At the outset of The Magical Mystery Tour, which premiered in black and white on Boxing Day but which was released in colour on 5 January this year, we are promised the “trip of a lifetime,” and, later on, we are assured that everyone is “having a lovely time.” Whether or not this includes the viewer is more open to question.

The Mystery Bus attempting to flee its critics.

The Mystery Bus attempting to flee its critics.

The movie has the loose framing premise of Ringo Starr taking his Auntie Jessie on a Mystery Bus tour, in the company of the other Beatles, a few swinging hip types, an assortment of British pensioners who seem a little nonplussed by the proceedings, and The Courier, a Number Two figure who leads the tour assisted by Miss Winters and Alf the Driver. What follows is a series of short musical interludes featuring a selection of numbers from the eponymous album, interspersed with sketches that are a cargo-cult cross between At Last The 1948 Show and The Prisoner, which seem to miss the point of either.

There’s a sketch with a sergeant-major drilling the tour participants; a sort of school games’ day and car race around an airfield or test track (featuring Angelo Muscat, the Butler in The The Prisoner); a whirlwind romance between Auntie Jessie and a character named Buster Bloodvessel; a tent in a middle of a field that turns out to be bigger on the inside than on the outside. But no real sense of what all this is supposed to be saying to the audience.

Yes, but why?

Yes, but why?

The highlights of the film are definitely the musical interludes. “Flying”, when seen in colour, is actually rather beautiful (which is rather lost in the black and white version). There are also short films for “Blue Jay Way,” featuring George Harrison playing on a chalk-drawing piano, and “Fool on the Hill”, with Paul McCartney standing on, well, a hill. Everything really comes together, though, in “I Am the Walrus”, with the surreal costumes of the performers echoing the imagery of the song, and the Beatles all seem to be enjoying themselves. This is far from true of the other sketches, in which John and, in particular, George seem more than a little surly.

Everyone having a lovely time, apparently.

Everyone having a lovely time, apparently.

The film hit its nadir, for me, with a rather disgusting dream sequence of Auntie Jessie being served mountains of sloppy spaghetti by John Lennon in a restaurant, while the bus crew sit around half-naked drinking milk. Similarly peculiar was the decision to have a sequence where the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band perform their song “Death Cab for Cutie” in a strip club complete with stripper, watched by George and John. And the movie more or less ends right there, with that sequence going straight into a 1950s Hollywood-musical-style production of “Your Mother Should Know.”

I’d say this is definitely one for Beatles completists more than anything else.

Two out of Five stars.

KGJ Weekly News is back! Come watch and find our what happened this week

by Gwyn Conaway

David Bailey's Box of Pin-Ups was released in 1964 in the United Kingdom but never made its way (officially) across the pond.

Today has gifted me with a much-desired treat: a suite of photographs by the infamous David Bailey titled Box of Pin-Ups. This is a defining collection of photography, and I’m saddened by its lack of accessibility here in the United States. It has taken all year to find such a treasure! Let’s delve, dear readers, into the work of the defining fashion photographer of our time.

From left to right: Reggie, Charlie, and Ronnie Kray. Why is Box of Pin-Ups not available in the United States, you ask? Why, none other than Lord Snowden, of course. He bemoaned the fact that the Kray brothers (above) are subjects of Bailey’s lens. True, the twins Ronnie and Reggie Kray are crime lords in the East End, but history proves time and time again that one’s virtue is not necessarily the trait that defines an era, nor one’s importance in capturing it. History finds both the hero and the villain equally fascinating.

David Bailey is an intriguing example of the working class artist rocketing to fame in the Swinging London scene. Suffering from both dyslexia and dyspraxia, a young Bailey had to seek out creative outlets as he completely and utterly abandoned his schooling. In fact, he left school when he was only fifteen years old, bounced around from job to job, and served in Singapore in the Royal Air Force. It was during this time that he bought his first camera, a Rolleiflex.

The Rolleiflex 2.8E is what I suspect his first camera to have been, released in 1956.

In 1960, a mere year into his career as a photographer, he began working with British Vogue, but it wasn’t until 1962 that he caught my eye. Vogue was beginning to promote younger fashions with a more modern feel, you see, and that work was to be done with a Rolleiflex. The camera is known for capturing movement and spontaneity, a must-have when photographing guerilla-style on the busy, gritty streets of Manhattan. So David Bailey and Jean Shrimpton, the Face of the 60’s herself, were tasked with a bare bones production. No hair or makeup artists. No lighted sets. Just the two of them, the photographer and the model, capturing what Bailey coined “Young Idea Goes West.”

Note the spontaneity of the images and how the fashions from Jaeger and Susan Small are caught in the flurry of New York life. British Vogue’s Lady Clare Rendlesham was reticent to feature this sort of realism in her magazine, which up until this point had focused on the aristocratic high polish of the 1950s.

I was so impressed with the journey of the series, seeing a young woman explore the wiles and wonders of the Big Apple. Truly, New York City is a chaotic and bustling town that is difficult to capture without having been there, walking down the streets at a clip. Bailey’s attention to this chaos is evident in the series, showcasing his mastery of the lens and celebrating his youth and boldness.

Bailey uses reflections in glass display windows and street poles to frame Shrimpton in the chaos of the city, while also capturing the candid reactions of local pedestrians as a way of framing Shrimpton’s role in this journey: a young woman full of wonder and wanderlust that can’t help but gain the attention of those around her.

Box of Pin-Ups is similarly youthful and bold. In fact, I’d venture to say that this is a seminal collection of photographs for more than one reason.

Firstly, a collection of photographs has never been sold in this manner before. It proves to me without a doubt that photographers of our times are cultural flames just like the models, fashion designers, and musicians they capture. I suspect we will see other photographers follow suit in the years and decades to come.

Secondly, the figures captured are not just the stars and starlets of our youth revolution. The collection includes such artists as Cecil Beaton, the famed war photographer, Rudolph Nureyev, the exceptional ballet danseur, and David Puttnam, an advertising executive. Bailey’s Box of Pin Ups captures the provocateurs of our times, the Swinging 60s, regardless of whether they’re already in the spotlight. His collection of movers and shakers is a look inward at the people inspiring our changing times.

From left to right: Cecil Beaton, David Puttnam, and Rudolph Nureyev.

However, the most interesting thing about the collection is actually distilled in the commentary of Francis Wyndham, who has included notes in the collection for each photograph. Wyndham astutely claims that “in the age of Mick Jagger, it is the boys who are the pin-ups.” This statement couldn’t hit the mark any more clearly than in Bailey’s collection. Only four of the subjects, out of thirty-six, are women.

This prompted me to look at the collection with even more sophistication. Bailey states it baldly in the title Box of Pin-Ups and in looking at his figures from that point of view, it’s clear that the male subjects are displaying their fashion choices – ergo their identities – with pride and vigor. This attention to vanity, as it’s often coined, is usually reserved for women’s modeling, fashion, and advertisement.

From left to right: The Beatles member John Lennon and record producer Andrew Oldham. Notice the unapologetic celebration of men's beauty here, in the delicate fanning on John Lennon's eyelashes and the bishop sleeve of Oldham's blouse.

Which invites the question: Has the arrival of sensations such as The Beatles, The Kinks, and Mick Jagger broken open a new era of male complexity? Since the early nineteenth century, men have been relegated to a very narrow range of roles. In fact, there was a concerted effort after the French Revolution to separate our material and social culture by gender: textiles, foods, furniture, colors, patterns, occupations, hobbies, education… And while women have been fighting these conventions for time immemorial, men have been conditioned to endure. Great minds, from Paul Gaugin to Oscar Wilde, have challenged these limitations, no doubt, but they have never been seen as the mainstream. Now, however, I see the potential for these defiant men to change our future. This fever our youth is currently experiencing… I hope it becomes much more than just a passing flu.

Thank you, David Bailey, for framing his answer to my question in the outlines of a beautiful box!