by John Boston

No-Sale, Sale

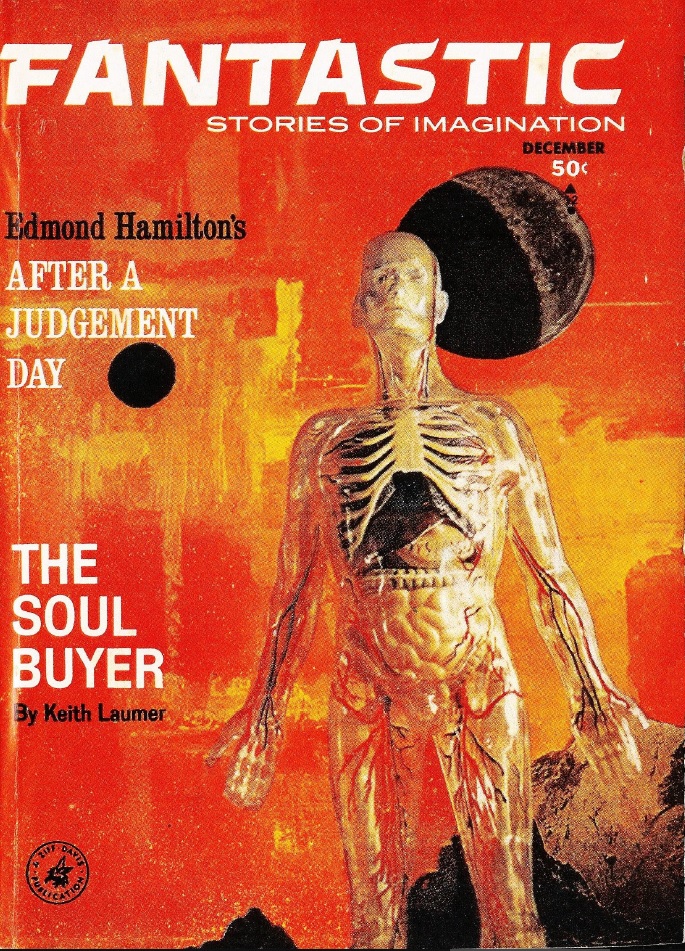

The big news, previously rumored, is that Amazing and its stablemate Fantastic are to change hands. The April Science Fiction Times just arrived, with the big headline “ ‘AMAZING STORIES’ AND ‘FANTASTIC’ SOLD TO SOL COHEN.” Cohen is the publisher of Galaxy, If, and Worlds of Tomorrow, but will resign at the end of next month to take up his new occupation.

Why is this happening? Probably because circulation, which had been increasing, started to decline again in 1962 (when I started reviewing it!). The SF Times article adds, tendentiously and questionably, that “the magazine showed what appeared to be a lack of interest by its editors.” Read their further comment and draw your own conclusions on that point.

Whatever the reason, it’s done. The last Ziff-Davis issues of both magazines will be the June issues. Whether they will continue monthly is not known, nor is who will edit the magazine—presumably meaning Cele Lalli is not continuing.

The Issue at Hand

by Paula McLane

The previous two issues were much improved over their predecessors. Of course the improvement could not be sustained (viz. the current issue), but it has at least reverted to the slightly less mean than on some occasions.

The Shores of Infinity, by Edmond Hamilton

by George Schelling

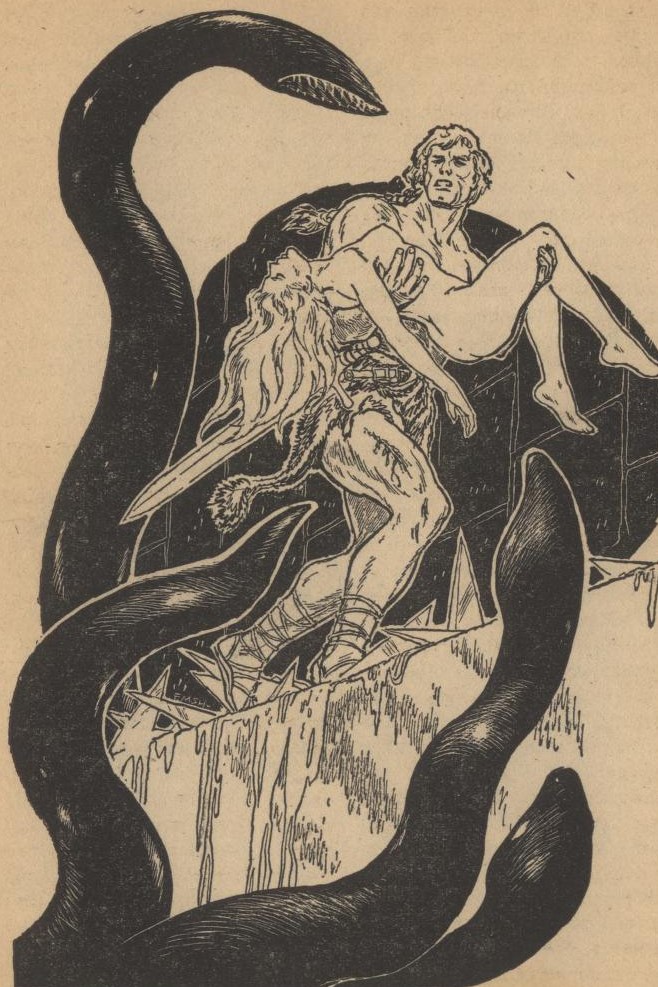

Who was it who first said “If you like this sort of thing, this is the sort of thing you will like”? Dorothy Parker? Mark Twain? Pliny the Elder? Anyway, Edmond Hamilton’s latest in his backwards-looking saga of the far future featuring the Star Kings may not even rise to the level of that truism. The generically titled The Shores of Infinity spends about 10 of its 33 or so pages on background and build-up, and then the generically named John Gordon of ancient (i.e., contemporary) Earth takes off to the capital of the Galaxy to hobnob with the Emperor in the imperial city of Throon.

There, he learns of more rumors of the previously encountered mind-controlling menace, is sent off on a dangerous secret mission to investigate, is captured, victimized by treachery and benefited by its reversal, and the author seems as bored by the whole perfunctory and hackneyed business as I was. It’s ostentatiously inconclusive, so we are guaranteed more. To paraphrase W.C. Fields, second prize would be two more sequels.

A recurring theme here is Gordon’s alienation from the beautiful Princess Lianna. This seems to be the special Woman Trouble issue of Amazing; see below. (Note to Betty Friedan: if the viewpoint characters were female, it would of course be the Man Trouble issue. Tell women more of them should be writing SF.) Also worth mentioning is the cover, by Paula McLane, which portrays a giant space-helmeted visage peering into a room where two small diaphanous figures are trying to close the door against him. Obviously metaphorical, right? Actually, it’s a quite literal rendering of a passing scene in the story.

Anyway, this one has little going for it except the usual space-operatic rhetoric (“The vast mass of faintly glowing drift that was known as the Deneb Shoals, they skirted. They plunged on and now they were passing through the space where, that other time, the space-fleets of the Empire and its allies had fought out their final Armageddon with the League of the Dark Worlds.”) The problem with this decoration is there’s not much here to decorate. Two stars, probably too generous.

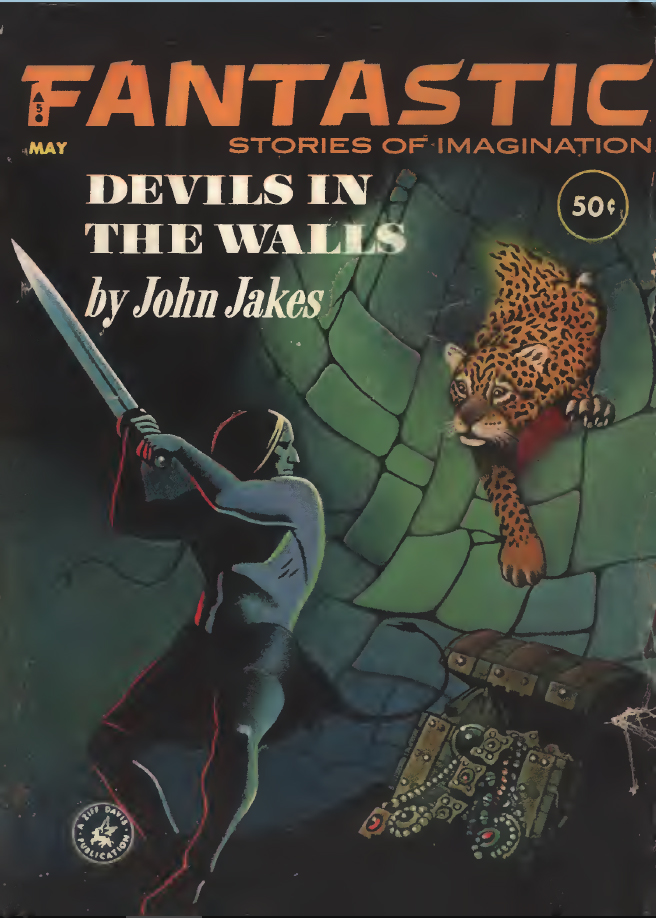

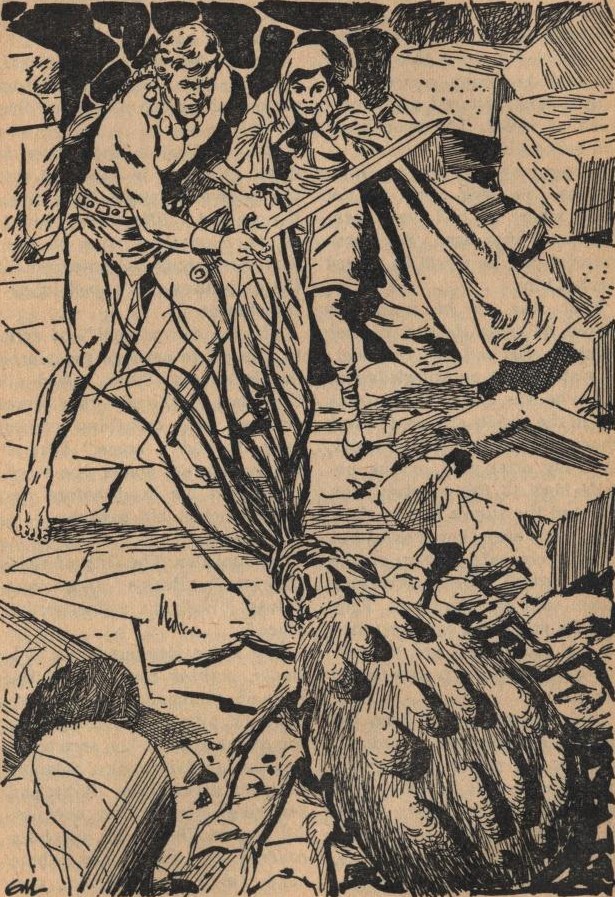

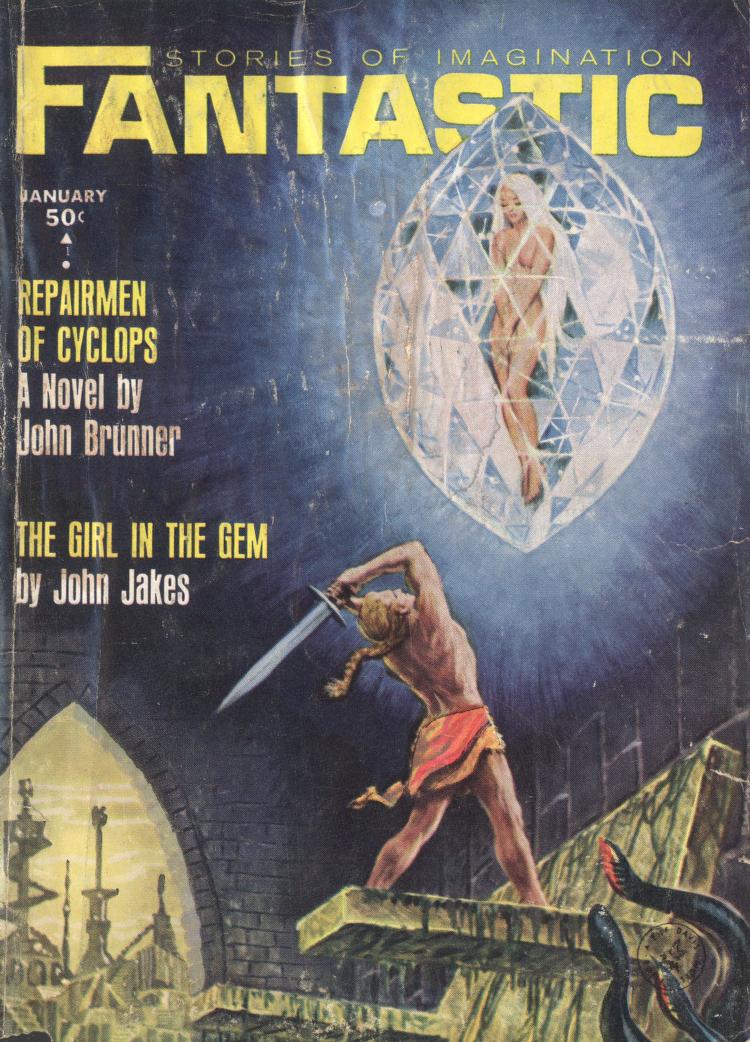

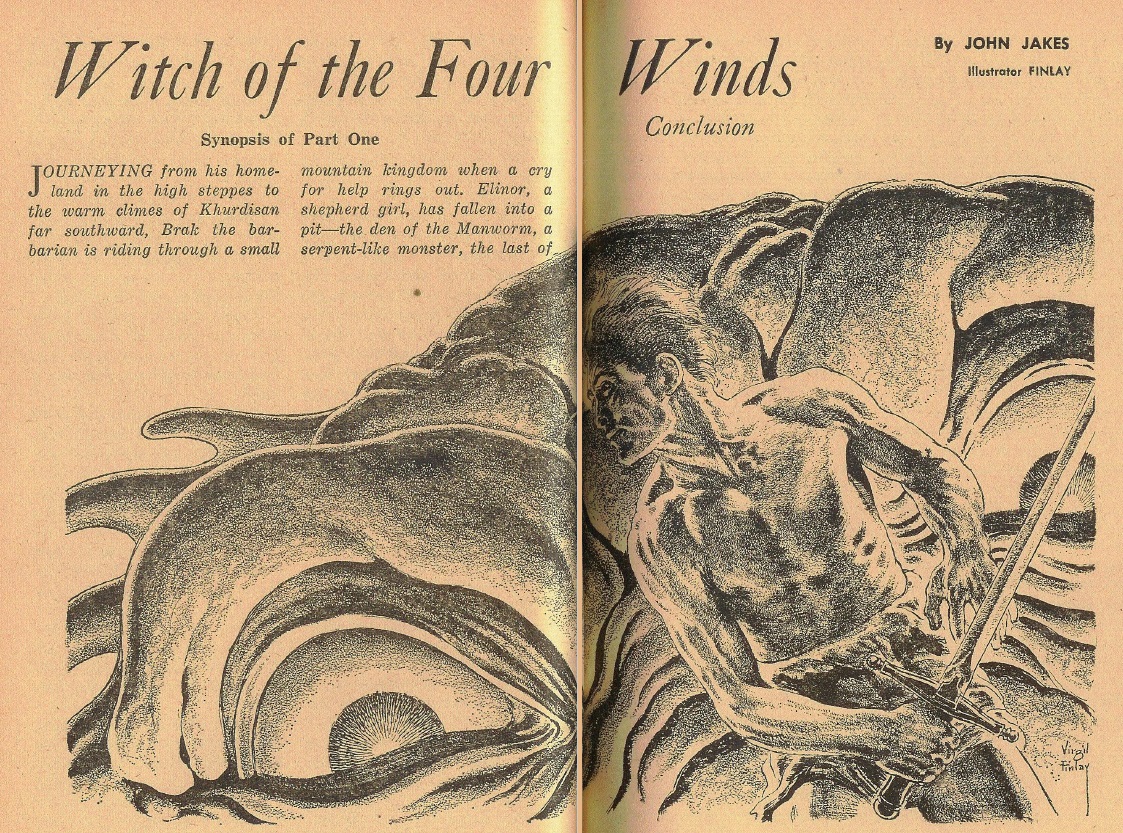

No Vinism Like Chau-Vinism, by John Jakes

by George Schelling

John Jakes’s long novelet No Vinism Like Chau-Vinism [sic], the title obviously a play on the all too familiar song There’s No Business Like Show Business, inhabits the territory demarcated by Pohl and Kornbluth’s The Space Merchants, Ron Goulart on a good day, and the Three Stooges. In the future, everything is showbiz. The populace is entertained and distracted by constant scripted and broadcast warfare between commercial forces, in this case the American Margarine Manufacturers Association versus the United Dairy Expedition Force, fighting of course in Wisconsin.

The script is disrupted by the appearance of a real gun in the hands of the rogue margarineer (Jakes calls them margies) Burton Tanzy of the Golden-Glo Margarine Company, who executes a cow on live TV, initiating a slapstick plot in which among other things besides real guns, the fake commercial war turns into a real union dispute. The protagonist Gregory Rooke of the Dairy forces must try to calm things down and restore order, lest the public get wind of the fraudulence of their world. His chief antagonist proves to be his ex-wife, who has dumped him to pursue her overweening ambitions, consistently with the Woman Trouble motif, though things work out better for Rooke than for poor forlorn John Gordon.

This story is actually quite amusing; Jakes has a knack for the farcical tall tale. Unfortunately it goes on too long and palls a bit by the end, keeping the final reckoning down to three stars.

De Ruyter: Dreamer, by Arthur Porges

Arthur Porges contributes Ensign De Ruyter: Dreamer, another in his tiresome series about the space navy guy who triumphs over cartoonishly stupid extraterrestrials through the clever use of basic science—in this case, it’s Fun with Electromagnetism. These stories barely rise to the level of filler. One star.

Greendark in the Cairn, by Robert Rohrer

Robert Rohrer continues in his “almost there” vein with Greendark in the Cairn, featuring a space captain who is either going nuts, or is being driven nuts by transmissions from the extraterrestrial enemy, but figures out how to defeat them and prevent himself from giving the game away. It’s gimmicky and facile but well rendered. Two stars, but do try again.

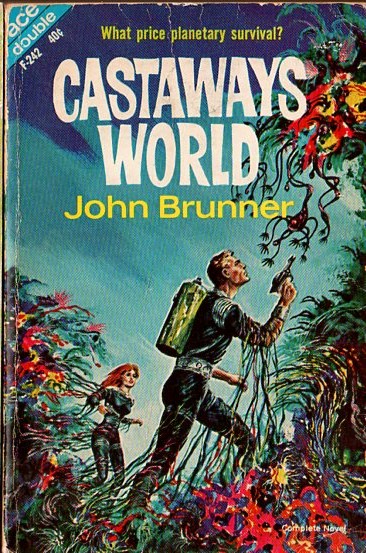

Speech Is Silver, by John Brunner

The earnest John Brunner undertakes a satire of American commercialism in Speech Is Silver, in which the protagonist Hankin is selected in the Soundsleep company’s “Great Search” for the man with the perfect voice for a program of sleep counseling—that is, counseling while one sleeps on how to handle the difficulties of the day. Except of course that’s not really how things work, and his new-found fame destroys his life. (Also—Woman Trouble again—his wife, who prodded him to enter the Soundsleep competition, leaves him, apparently because he was never ambitious enough, like Rooke’s wife in No Vinism [etc.].) At the point where Soundsleep decides to replace him with a younger near-double, Hankin detonates.

Like the Jakes story, this one is an acid satire on contemporary image-mongering American capitalism. Its problem, aside from being too long (also like Jakes), is that it isn’t crazy enough. Brunner’s calm and methodical style and storytelling muffle the plot’s antic qualities. Maybe he should get Jakes to introduce him to the Three Stooges.

Two stars.

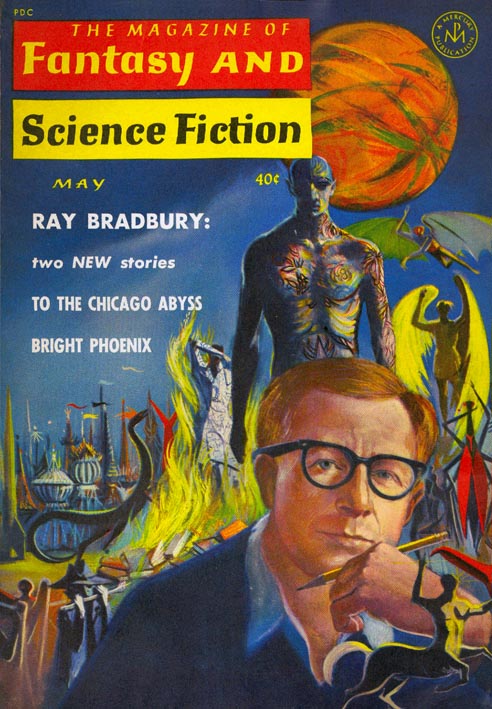

Religion in Science Fiction: God, Space, and Faith, by Sam Moskowitz

Sam Moskowitz forges on with Religion in Science Fiction: God, Space, and Faith, rendered on the cover as Science-Fiction Views of God With a Profile of C.S. Lewis. It’s a rambling description of various SF stories on religious themes, starting reasonably interestingly with several older books that most readers will not have heard of, continuing with the promised account of C.S. Lewis, followed by Stapledon, Heinlein, Wyndham, Simak, Leiber, Keller, Bradbury, Blish, Miller, del Rey, Boucher, and Farmer.

In this recitation Moskowitz manages to miss Arthur C. Clarke’s Hugo-winning The Star and his equally well-known The Nine Billion Names of God; Isaac Asimov’s The Last Question; Leigh Brackett’s tale of a different sort of theocracy, The Long Tomorrow; Harry Harrison’s anti-theological polemic The Streets of Ashkelon; Katherine MacLean’s acerbic Unhuman Sacrifice; and, astonishingly, Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land. Remarkably, he says, “Heinlein, who introduced [religion] into the science fiction magazines, has long since tired of it as a focal plot device.”

But this (mis-)observation does not deter him from his conclusion: “Neverthess, the decision is made. The science fiction writer has come to the conclusion that scientific advance will not mean the end of belief. He feels certain that a truly convincing portrayal of a hypothetical future cannot be made without considering the mystical aspects of man.”

Can we say fallacy of composition? Two stars: another “almost,” some interesting material, some of it unfamiliar, the whole brought down by Moskowitz’s fatuous generalizations.

Summing Up

So, mostly not too bad (except for the egregious Ensign Ruyter), but mostly not as good as it should and could have been either. There have been issues that would make one regret that this regime is ending, but this isn’t one of them.

![[March 12, 1965] Sic Transit (April 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/amz-0465-cover-672x372.png)

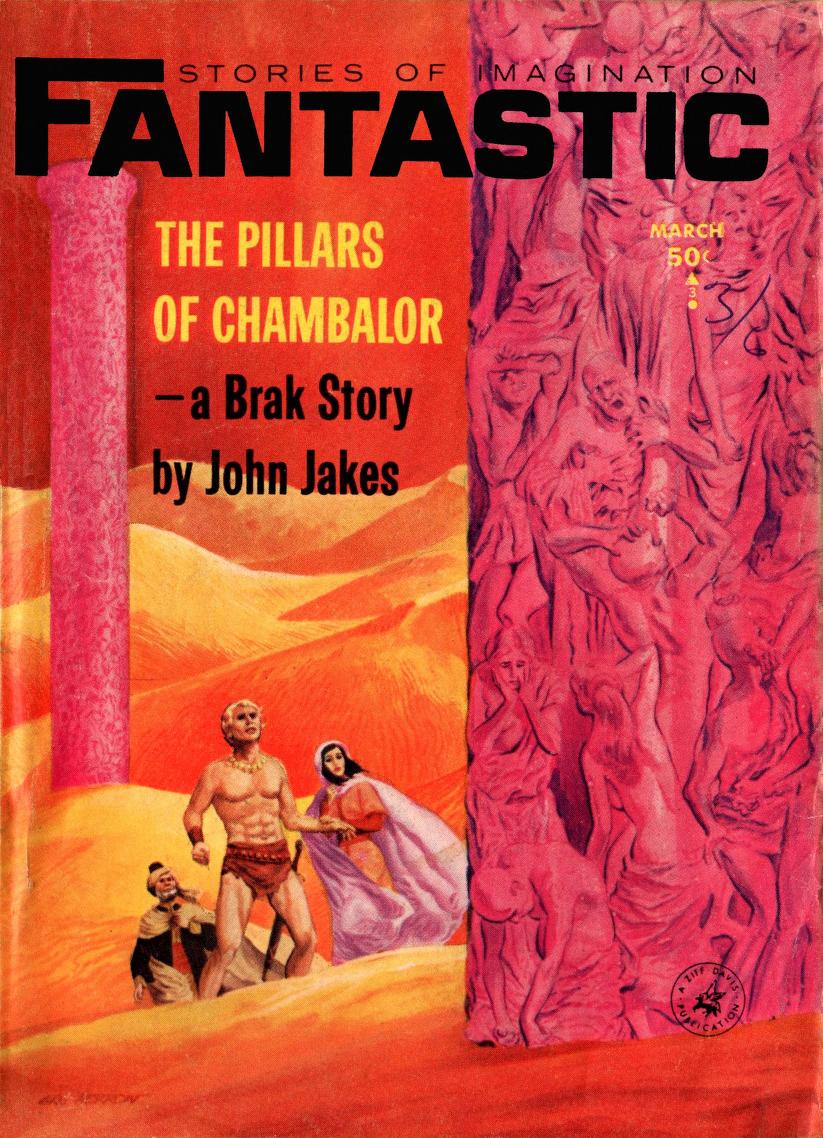

![[February 22, 1965] Theory of Relativity (March 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Fantastic-v14-n03-1965-03_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

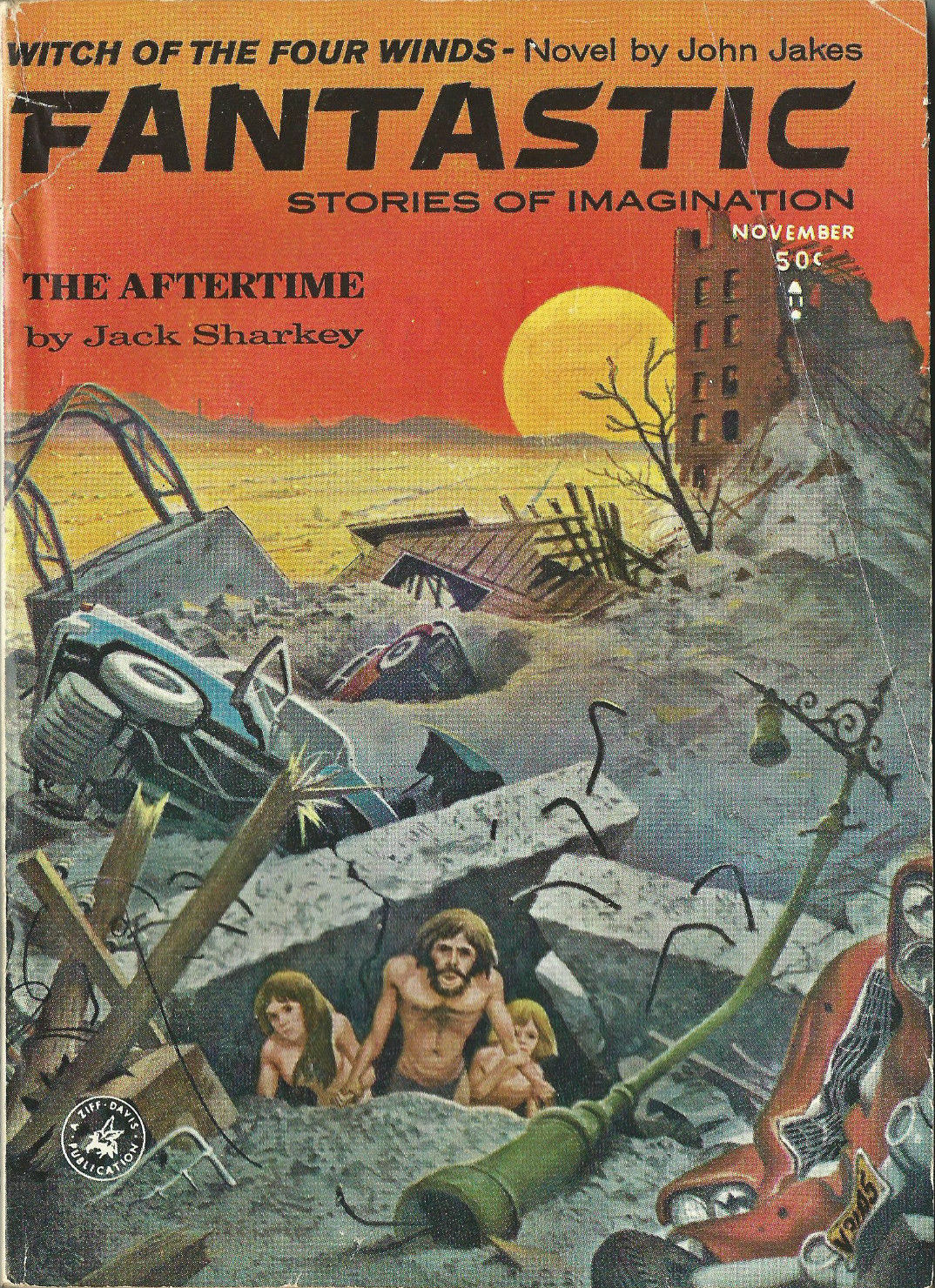

![[December 23, 1964] Odds and Ends (January 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Fantastic_v14n01_1965-01_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[August 25, 1964] Combat Zones (September 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FANTSEP1964-e1565757244659-427x372.jpg)

![[July 20, 1964] Dashed Hopes (August 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/26179-400x372.jpg)

![[November 25, 1963] State of Shock (December 1963 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631125cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 24, 1963] Sounds Familiar (November 1963 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631024cover-672x372.jpg)