by Victoria Silverwolf

Old Series Never Die, They Just Fade Away

Summertime is right around the corner, here in the Northern Hemisphere, and all patriotic Americans know what that means; reruns on television. Not only does this save the production companies money, it allows defunct programs to continue to appear on TV screens long after they're gone, like ghosts haunting a house. (Of course, they're easier to exorcise than traditional specters; just pull the plug.)

Two popular, critically acclaimed, and long-running series recently cast off this mortal coil, ready to enter the monochromatic afterlife of reruns.

Late last month, the courtroom drama Perry Mason slammed down the gavel for the last time with The Case of the Final Fade-Out. The story involved a television studio, so a large number of crew members made cameo appearances, pretty much as themselves. There was also a very special guest star.

That's executive producer Gail Patrick Jackson on the left and Hollywood columnist Norma Lee Browning on the right. The fellow in the middle? That's bestselling author Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason, dressed up for his role as a judge in the final episode.

At the start of this month, The Dick Van Dyke Show came to a conclusion with the appropriately titled episode The Last Chapter. Van Dyke's character, television writer Rob Petrie, finishes the book he's been working on for five years, and looks back on his life.

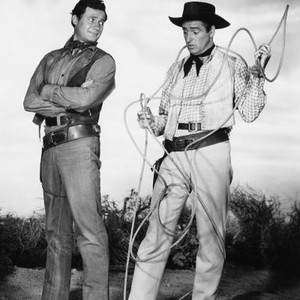

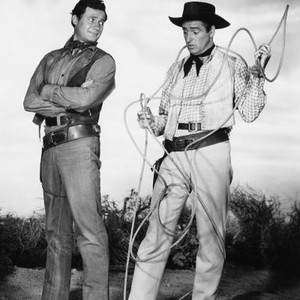

Because The Last Chapter was really just an excuse to reuse sequences from previous episodes, I'm offering you this scene from the penultimate episode, The Gunslinger. Surrounding Van Dyke in this Western parody are cast regulars Mary Tyler Moore and Richard Deacon.

I'm sure that both of these hit series will be reincarnated in American living rooms for quite a while.

Not all summer television programming consists of reruns, to be sure. There are so-called summer replacement series as well. In a week or so, we'll enjoy (or avoid) the first episode of The Dean Martin Summer Show (not to be confused with The Dean Martin Show, which has been going on since last year. Are you still with me?) It will be hosted by the comedy team of Dan Rowan and Dick Martin.

Rowan on the left and Martin on the right, in a scene from their 1958 Western spoof Once Upon a Horse. I wonder if they'll have any success as TV hosts.

A Home Run The First Time At Bat

Although it's not unknown for popular songs of yesteryear to return to the charts — auditory reruns, if you will — listeners are usually searching for something original. Newcomer Percy Sledge offers an notable example with his smash hit When a Man Loves a Woman. This passionate, soulful ballad, currently Number One in the USA, is not only the first song recorded by Sledge, it is the first song recorded in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, a city famous for its music studios, to reach that position.

Your fans mean it, Mister Sledge.

I've Seen This All Before

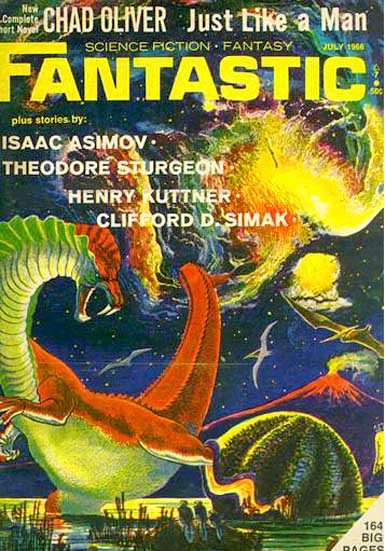

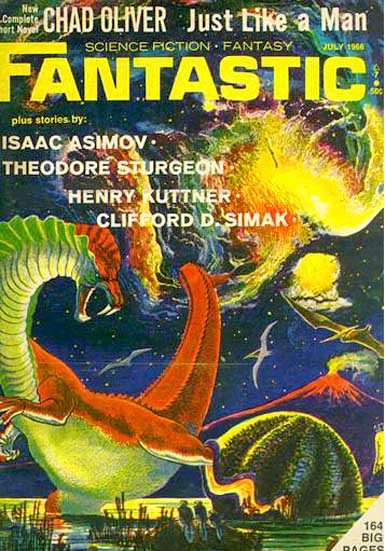

The reason I've been talking about reruns, before I get to the contents of the latest issue of Fantastic, isn't just the fact that they've been filling up the magazine with reprints for some time now. As we'll see, many of the old stories in this issue have reappeared several times before. Reruns of reruns, so to speak. Whether fans of imaginative literature will be willing to spend four bits for fiction they may have already read in collections or anthologies remains to be seen.

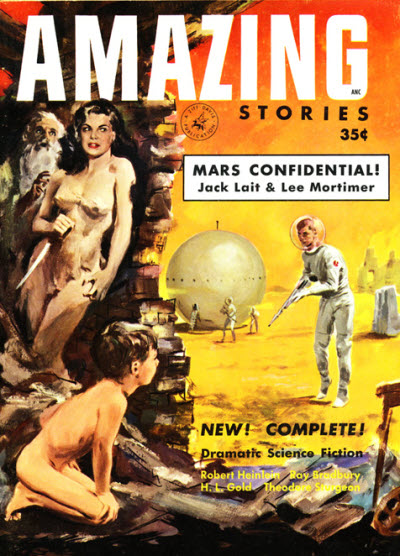

Cover art by Frank R. Paul.

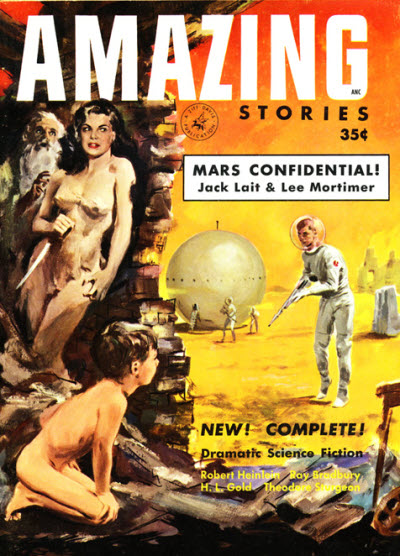

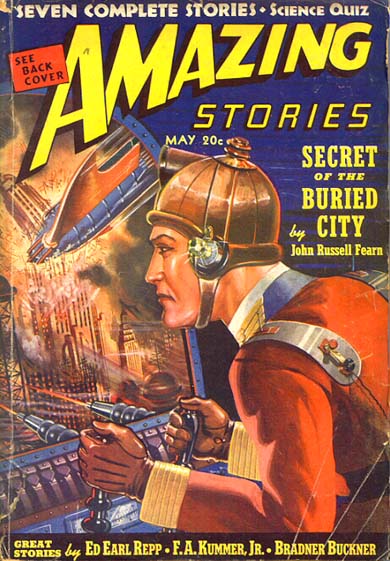

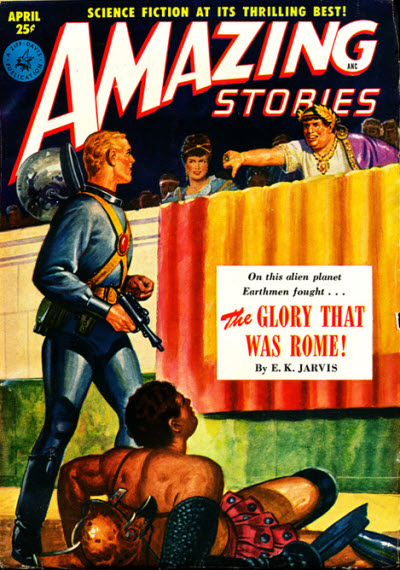

Predictably, the front cover is also a rerun.

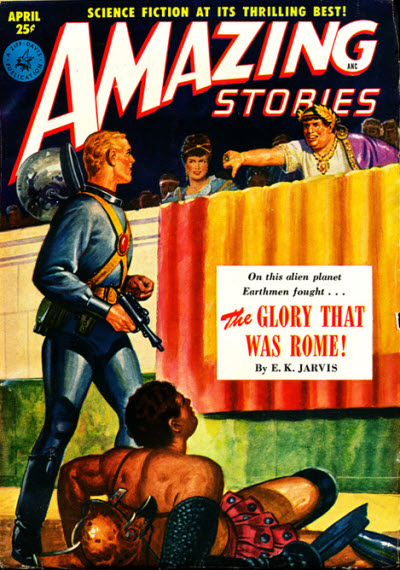

The back cover of the June 1943 issue of Amazing Stories. It looks better in the original version.

Before I get to the reruns, however, let's start with something new.

Just Like a Man, by Chad Oliver

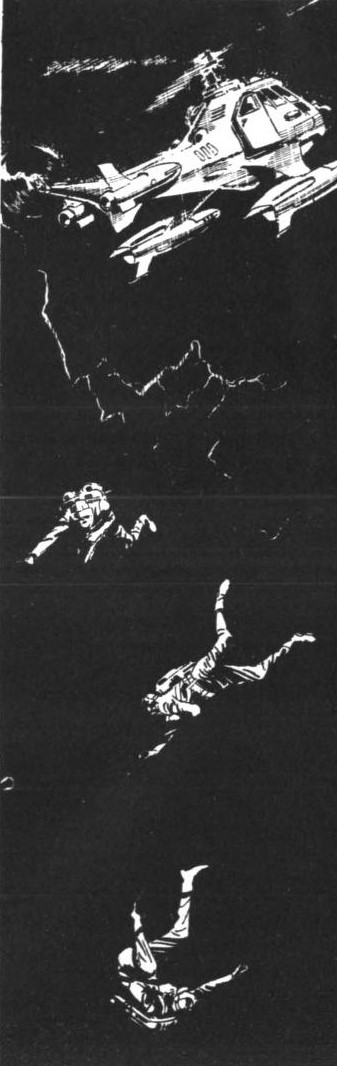

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

Three men are in an aircraft, flying over the surface of an Earth-like planet. A sudden storm forces them to abandon the vehicle, stranding the trio in an area resembling an African savannah. Because the place is full of leonine predators, they hightail it to the relative safety of a nearby rainforest.

Climbing one of the planet's gigantic trees in order to get away from the hungry cats.

They wind up far above the ground, among an unsuspected community of highly intelligent primates. These mysterious creatures help them survive, and even offer the possibility of reaching their home base, located five hundred miles away across uncharted wilderness.

Among the primates, who are not as hostile as shown here.

This is a decent tale of adventure, and the enigmatic primates are interesting. The planet is so similar to Earth — the feline predators are pretty much just lions — that you might forget you're reading a science fiction story. Overall, it's worth reading, if not outstanding in any way.

Three stars.

The Trouble With Ants, by Clifford D. Simak

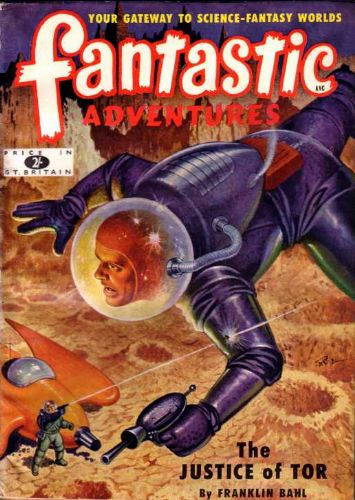

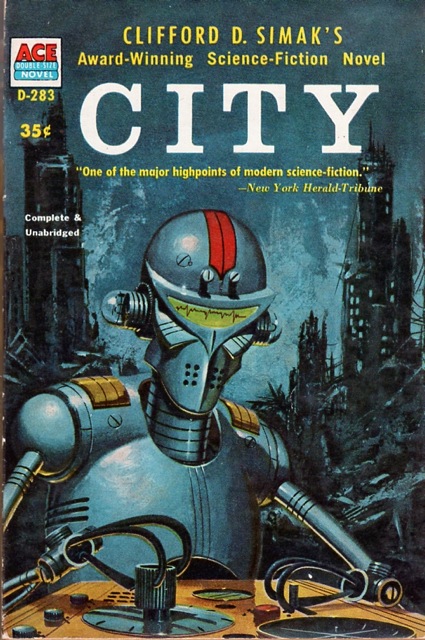

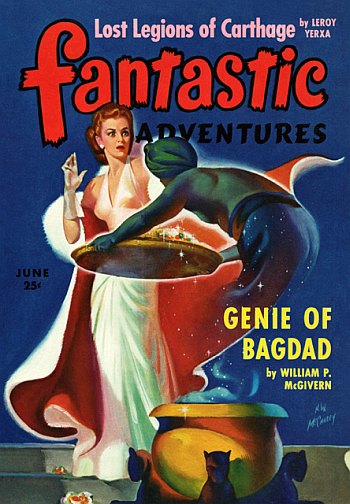

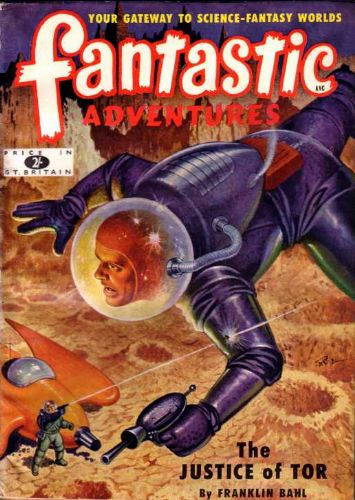

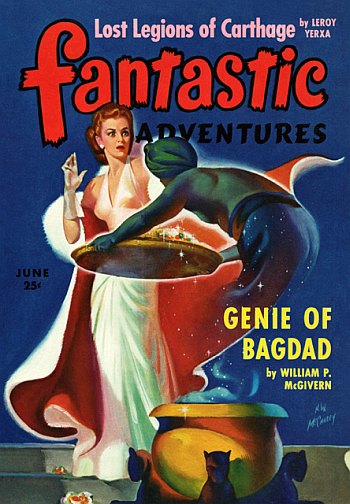

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones.

From the January 1951 issue of Fantastic Adventures comes this final story in the author's famous City series. (By the way, the title of this work was changed to The Simple Way when it appeared in book form.)

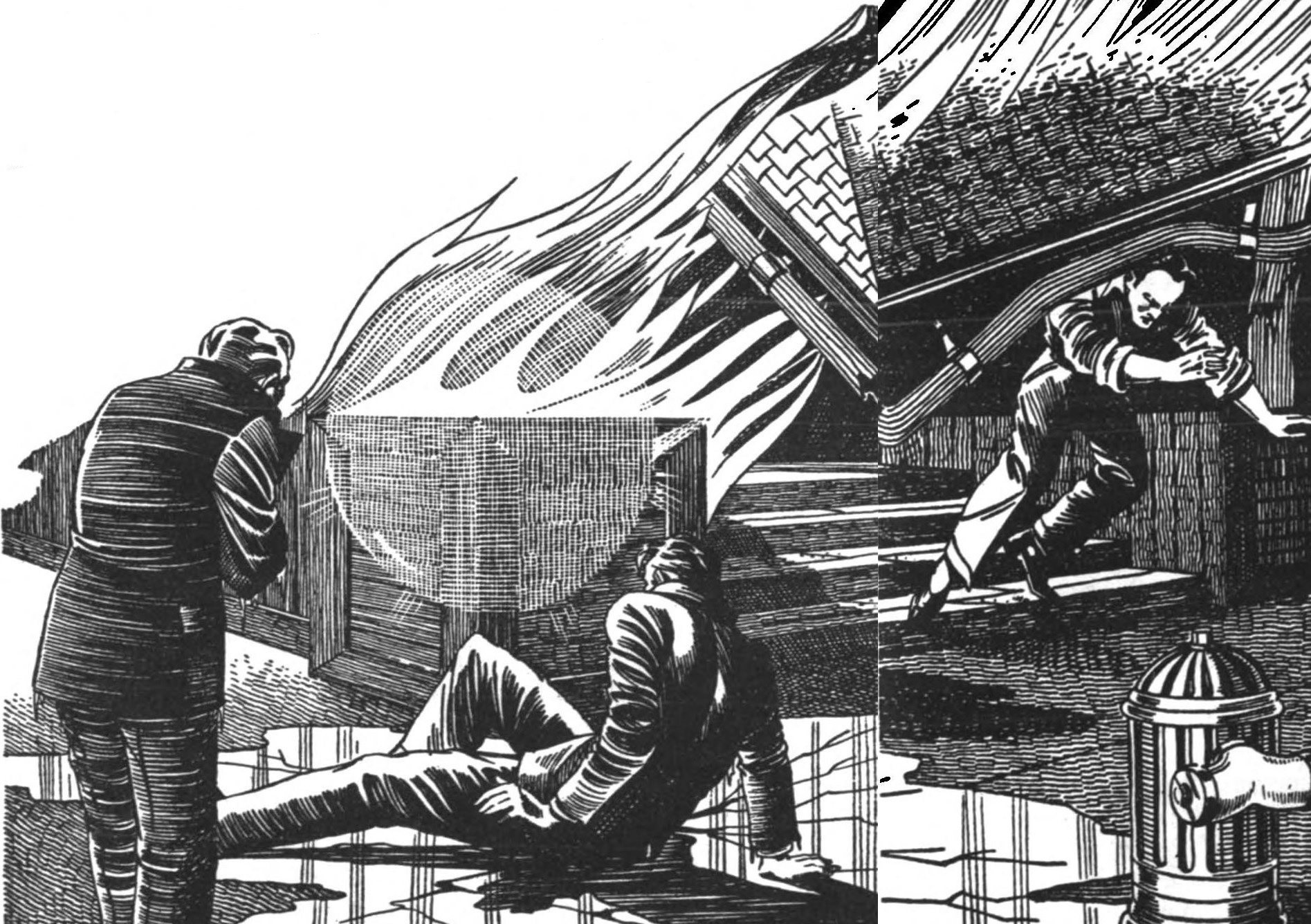

Illustration by Rod Ruth. From this point on, all the illustrations are reruns from the original appearances of the stories.

In the far future, people are gone from Earth, with the exception of one fellow in suspended animation. Long ago, humans increased the intelligence of dogs, gave them the power of speech, and built robots to serve their needs. The canines, in turn, taught other animals to speak.

Complicating matters is the fact that a man caused ants to develop technology of their own, including robots the size of fleas. Now the ants are constructing a building, for an unknown purpose, which threatens to take over the planet.

An ancient robot returns from humanity's new home in a mysterious fashion. It seeks out the man in suspended animation as part of its quest to understand the ants.

Brought together as a fix-up novel in 1952, the City series won the International Fantasy Award the next year. It is usually considered a classic of science fiction, and has been reprinted many times.

One of the many editions of this work. Cover art by Ed Valigursky.

Highly imaginative, and with a sweeping vision of the immensity of time, Simak's tales also have a gentleness and intimacy that touches the reader's heart. The mood is one of quiet melancholy, and the acceptance of the fact that all things will pass away.

Although SF fans are likely to have read this story before, its quality makes it a welcome repeat. (One can rarely say the same thing about television reruns, or else viewers would stay glued to their screens.)

Five stars.

Where Is Roger Davis?, by David V. Reed

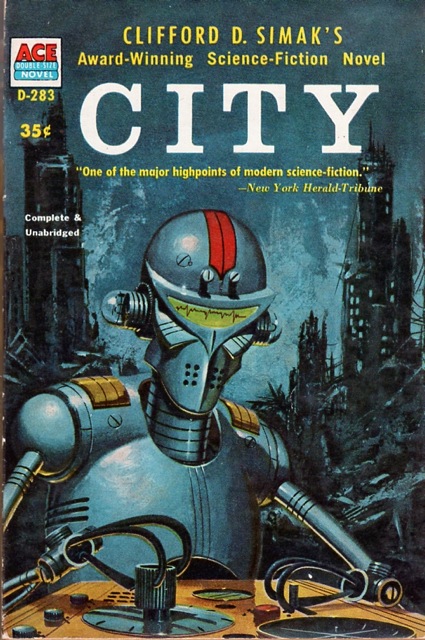

Cover art by Robert Fuqua.

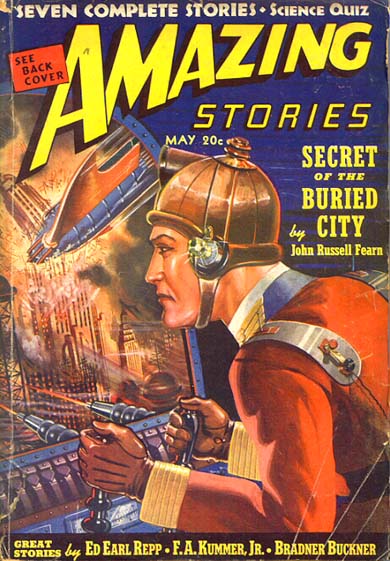

Let's take a break from stuff that has already been reprinted multiple times, and take a look at the first reappearance of this yarn, taken from the yellowing pages of the May 1939 issue of Amazing Stories. (The author is unknown to me, but I have discovered that he also writes for comics, particularly Batman. Apparently a couple of episodes of the new television series are based on his scripts for the comic book.)

Illustrations by Julian S. Krupa.

Two young men working for a New York City tour bus encounter an invisible, telepathic Martian. One of them is seduced by the alien's plot to take over the world, and soon becomes a megalomaniac.

The fact that the Martian makes robbing a bank as easy as pie is another factor in his decision.

The other fellow has to figure out a way to keep the Martians from conquering Earth.

The mood of the story changes drastically from light comedy at the start to grim tragedy by the conclusion. Given the year it was written, I wonder if the dictatorial intentions of the first man were influenced by the rise of Fascism.

The author claims that this story is a true account, sent to him by the second man. There are also bits of imaginary news articles scattered throughout, in an attempt at verisimilitude. These don't work very well, particularly the long one at the end. The only thing I found mildly intriguing, if implausible, was the way the hero manages to plot against beings who can read his mind.

Two stars.

Almost Human, by Tarleton Fiske

Cover art by Harold W. McCauley.

The introductory blurb makes it clear that the author of this story, reprinted from the June 1943 issue of Fantastic Adventures, is really Robert Bloch, using a rather absurd pseudonym. (As is common practice, this was done because he had another story in the same issue under his own name.)

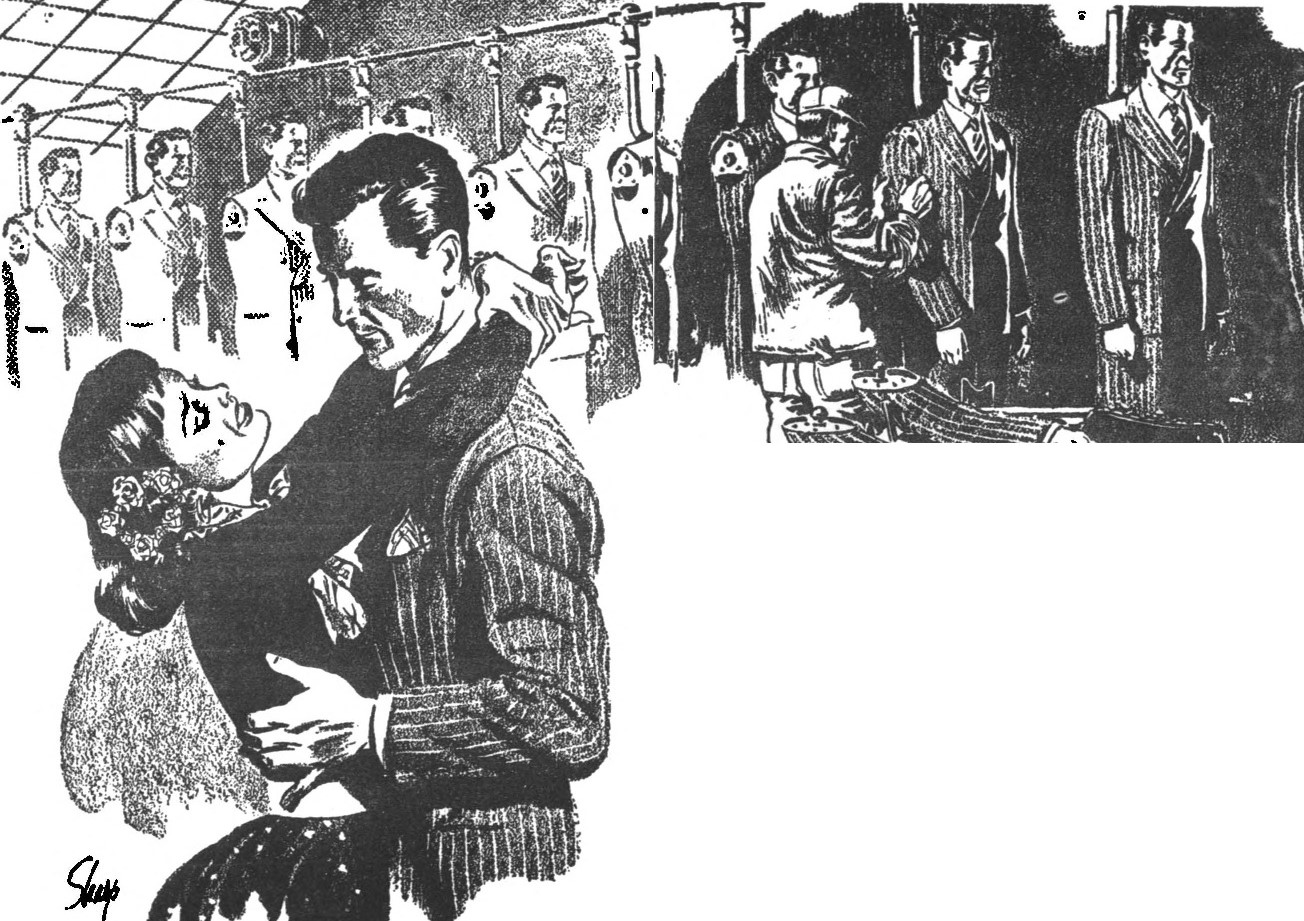

Illustration by Rod Ruth.

A hoodlum makes his way into the secret laboratory of a brilliant scientist. His moll has been working for the guy, so the crook knows the genius has created a robot. The machine is being educated like a child. The gangster teaches it to be an invincible criminal, and to kill without mercy. As you'd expect, things don't work out very well.

This piece reads like hardboiled fiction from a crime pulp. The final scene is particularly gruesome, in typical Bloch style. The author shows a certain knack for the Hammett/Chandler mode, but that's about all I can say for it. Not that great a story, but somebody thought it was worth reviving for an anthology.

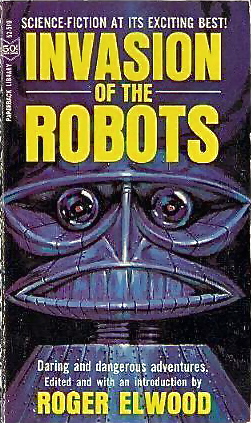

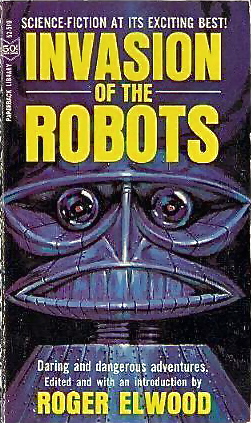

Cover art by Jack Gaughan.

Two stars.

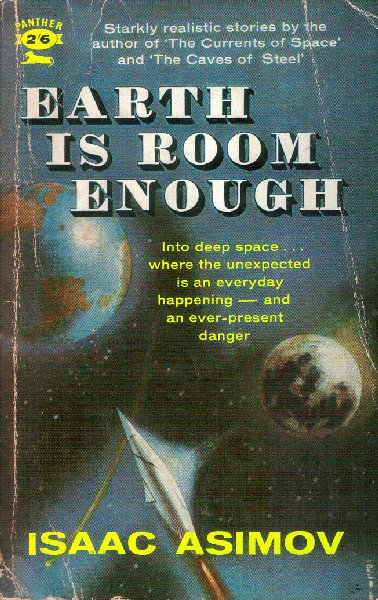

Satisfaction Guaranteed, by Isaac Asimov

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones.

Speaking of robots, here's one of several stories about the robopsychologist Susan Calvin by the Good Doctor, from the April 1951 issue of Amazing Stories.

Illustration by Enoch Sharp.

Calvin only plays a minor part in this story, which focuses on a rather mousy, insecure housewife. Her husband works for the same robotics firm as Calvin, so he brings home a test model of a new machine. It looks like a handsome young man, and is designed to be helpful around the house in many different ways. The husband goes off on a business trip, leaving his wife alone with the robot.

The housewife is frightened of it at first, but soon learns to accept it. It even helps her with home decorating, clothing, and makeup, so she learns self-confidence. A final, unexpected gesture on the part of the machine, seemingly out of character for a robot, wins her the envy of her snobbish acquaintances. Susan Calvin explains why the machine's action was a perfectly logical way of obeying the famous First Law of Robotics.

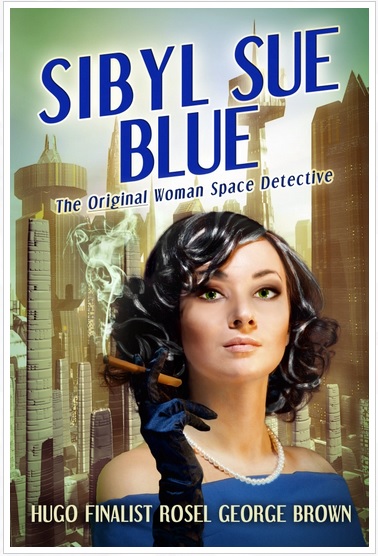

Anonymous cover art for a British edition.

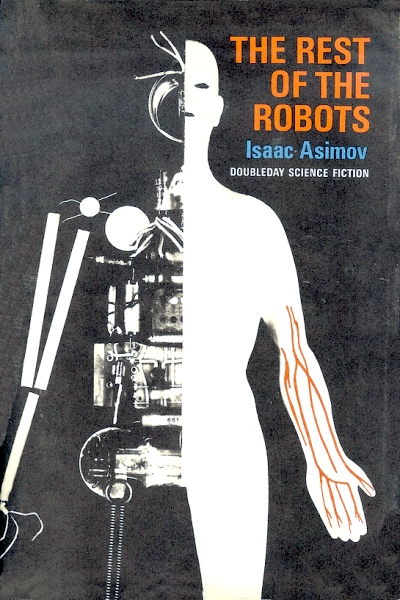

The author must be fond of this tale, because he has already included it in two different collections of his work. The one shown above, as the title indicates, includes stories that take place on Earth rather than in space, despite the misleading illustration and blurb. The story also appears in an omnibus that brings together his two robot novels as well as several shorter works.

Cover art by Thomas Chibbaro.

Besides that, it is also included in the same Roger Elwood anthology as Bloch's story. My sources in the television industry tell me that it is being adapted for the British series Out of the Unknown, and should appear late this year. (Will there be American reruns? One can only hope.)

Is it worth all this attention? Well, it's not a bad yarn, if not the greatest robot story Asimov ever wrote. The housewife is something of a stereotype of an overly emotional female, dependent on a man for her happiness. (This is in sharp contrast to the highly intelligent and independent Doctor Susan Calvin.) At some point you may think that the author is violating his own rules about robot behavior, but it's all explained at the end.

Three stars.

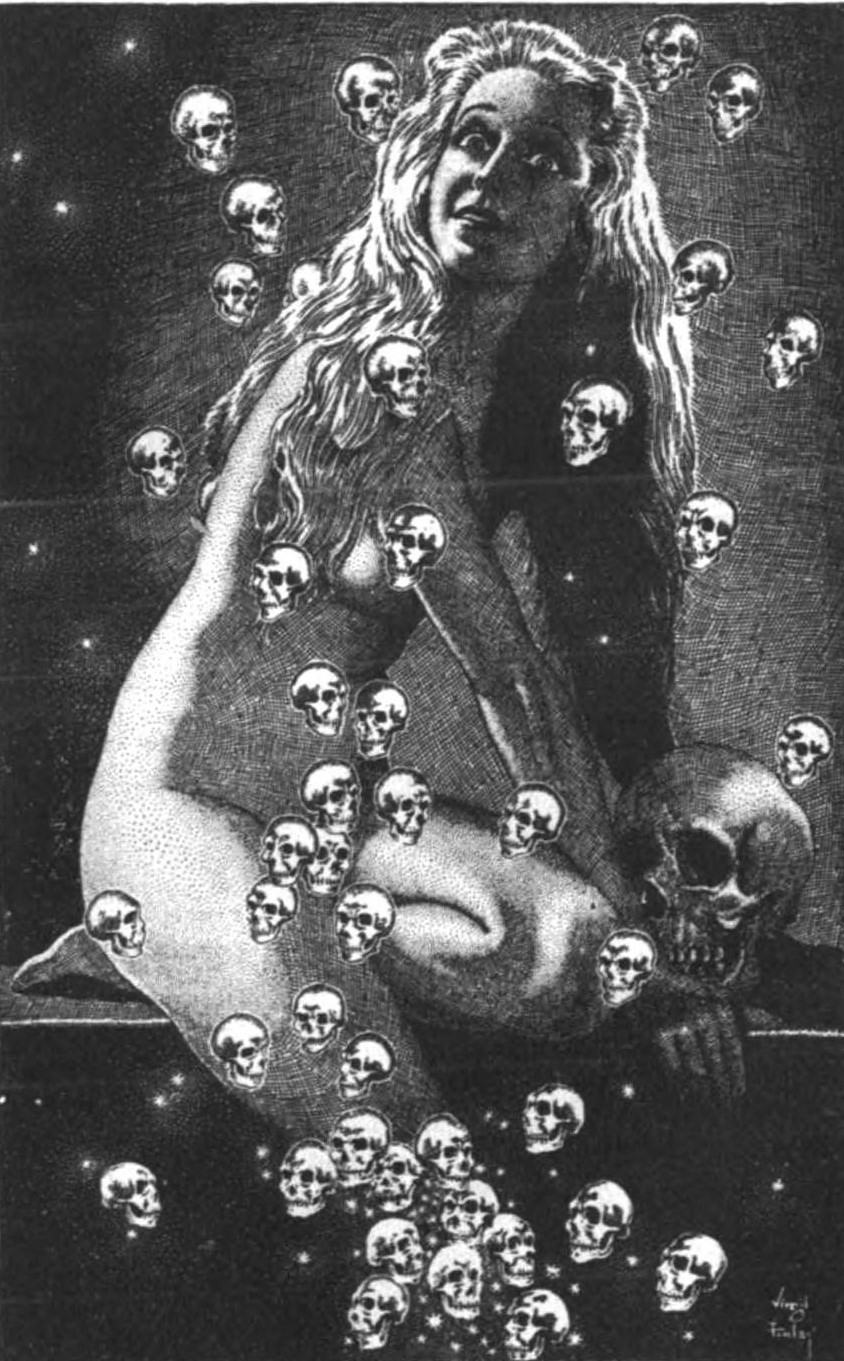

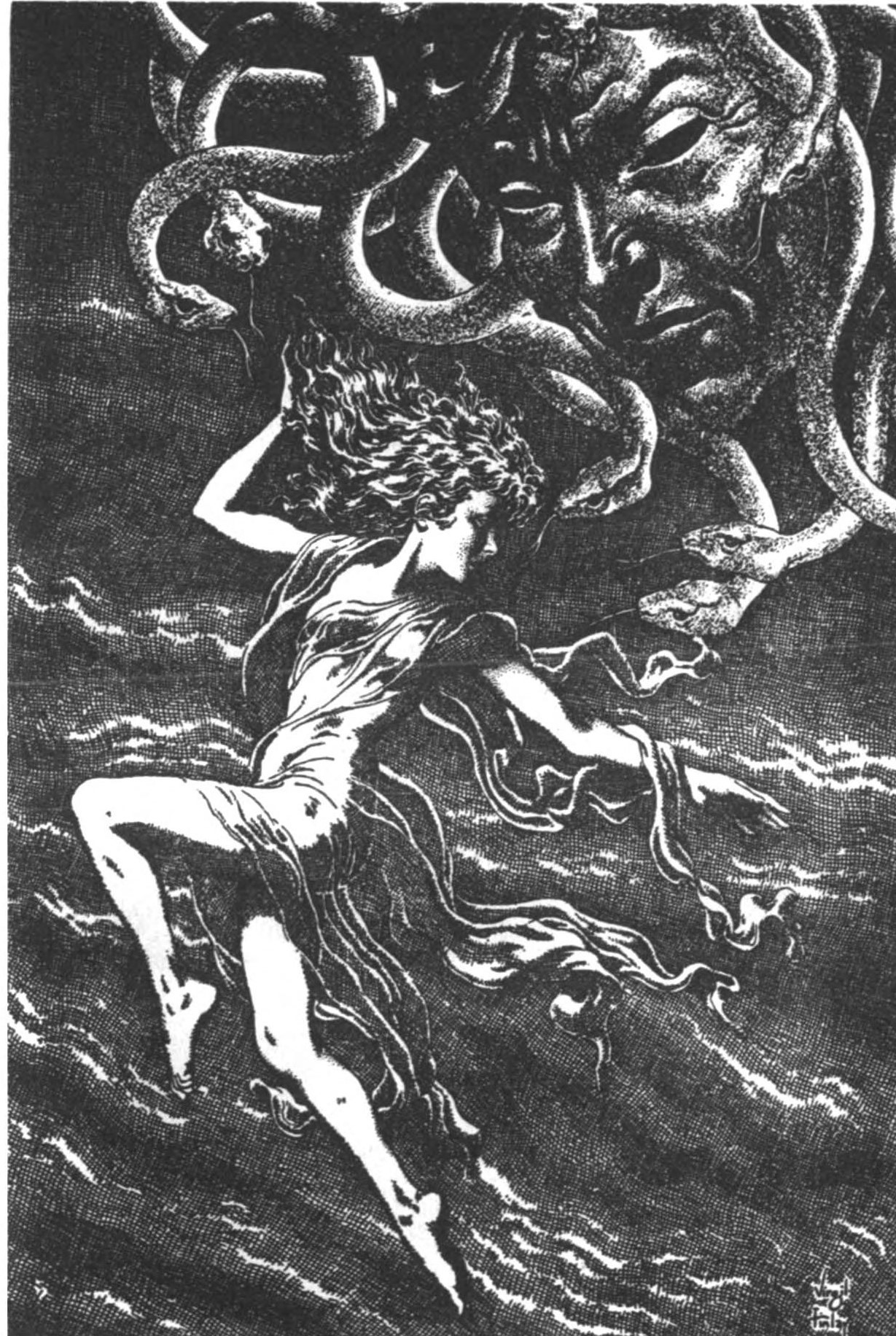

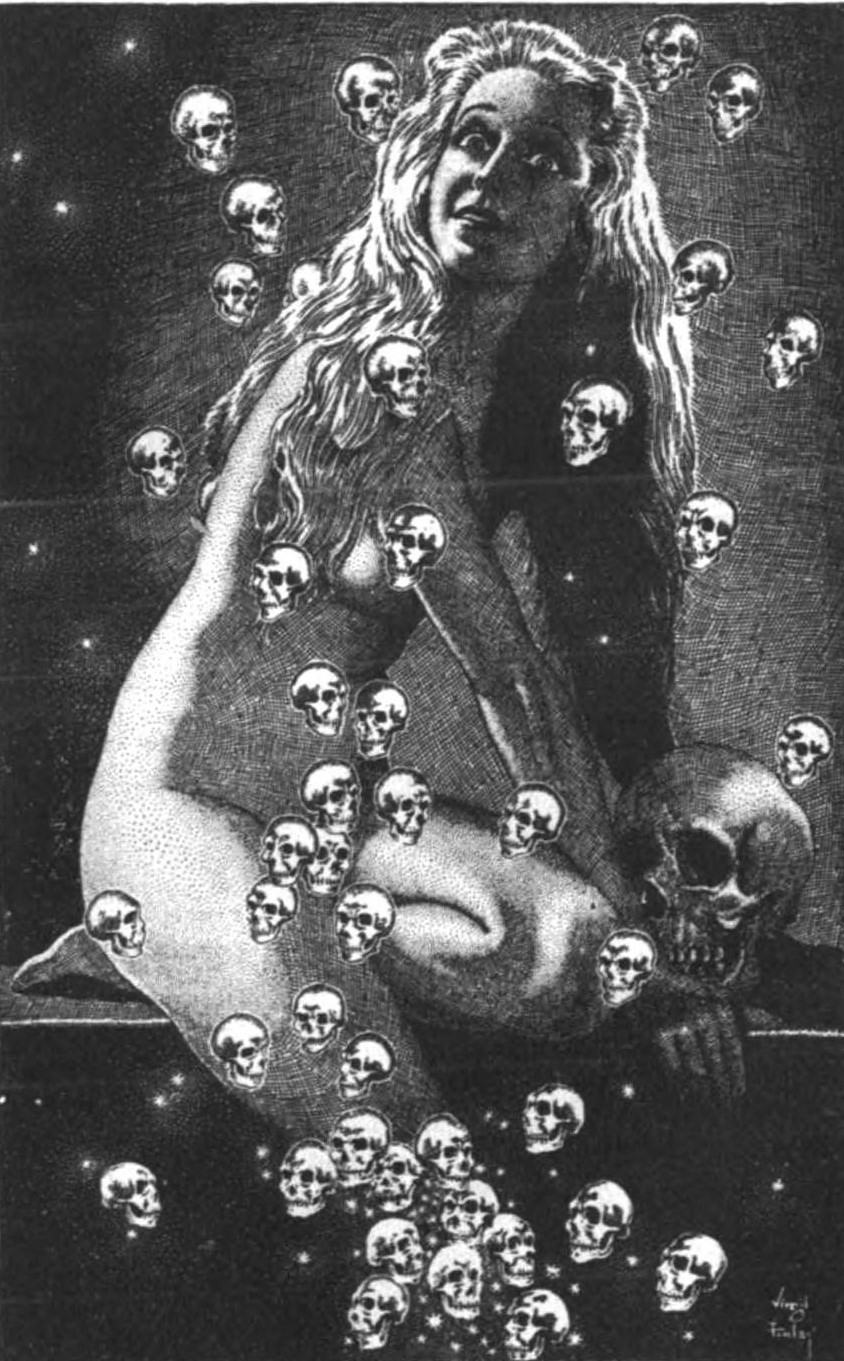

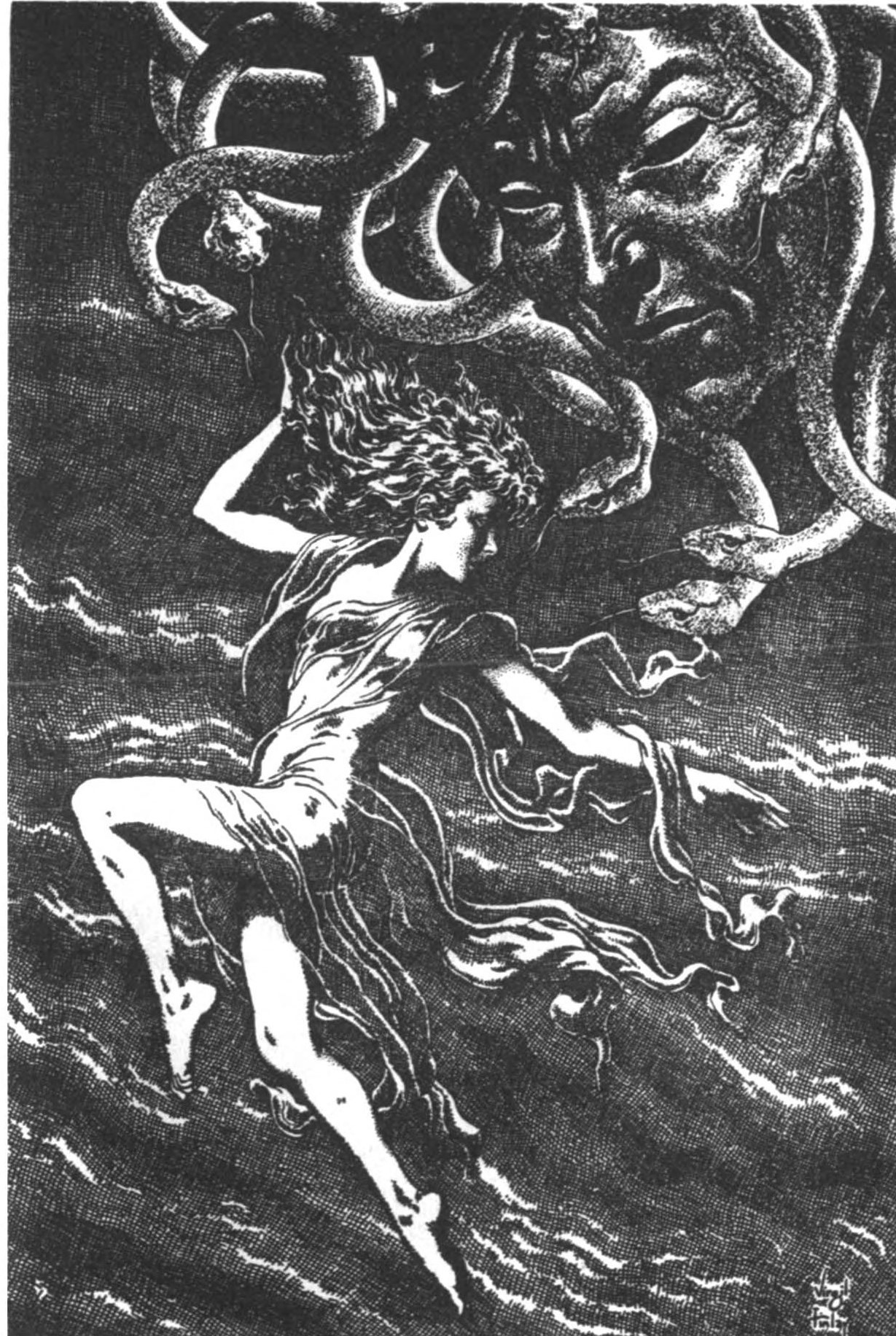

A Portfolio – Virgil Finlay

I'm not sure if I should even discuss this tiny collection of illustrations by the great artist, but at least I can share them with you.

For The New Adam (1939) by Stanley G. Weinbaum. The magazine calls it The New Atom, which is an egregious error.

For Mirrors of the Queen (1948) by Richard S. Shaver.

For The Silver Medusa (1948) by Alexander Blade (pseudonym for H. Hickey.)

What can I say? His work is stunning.

Five stars.

Satan Sends Flowers, by Henry Kuttner

Cover art by Robert Frankenberg.

The January/February 1953 issue of Fantastic is the source of this variation on an old theme.

Illustrations by Tom Beecham.

A man sells his soul to the Devil in exchange for immortality. (The premise is similar to that of the Twilight Zone episode Escape Clause, but the twist ending is different.) He ensures that he will remain young, healthy, and all that, so Satan can't play any tricks on him. Obviously, he figures he'll never have to pay up.

The Devil demands surety in the form of certain subconscious memories the fellow possesses. After assuring him that he won't even know he's lost anything, the man agrees. Unafraid of either earthly punishment or damnation, he lives a life of total depravity.

His first crime is the murder of his mother.

Eventually, he persuades the Devil to give him back what he lost, even though Satan warns him that he won't like it. This turns out to be a bad idea.

Like most other stories in this issue, this one has already appeared in a book. (It acquired the new title By These Presents.)

Back and front cover art by Richard Powers.

I should mention that the husband-and-wife team of Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore almost always collaborated, even if the resulting story appeared under only one name. Whoever might have been responsible for whatever parts of this work, it's a reasonably engaging tale. I'm not sure I really accept the explanation for what the man's unconscious memories represent, but I was willing to go along with it.

Three stars.

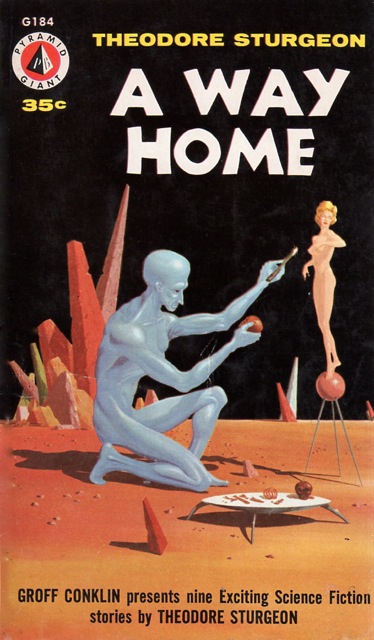

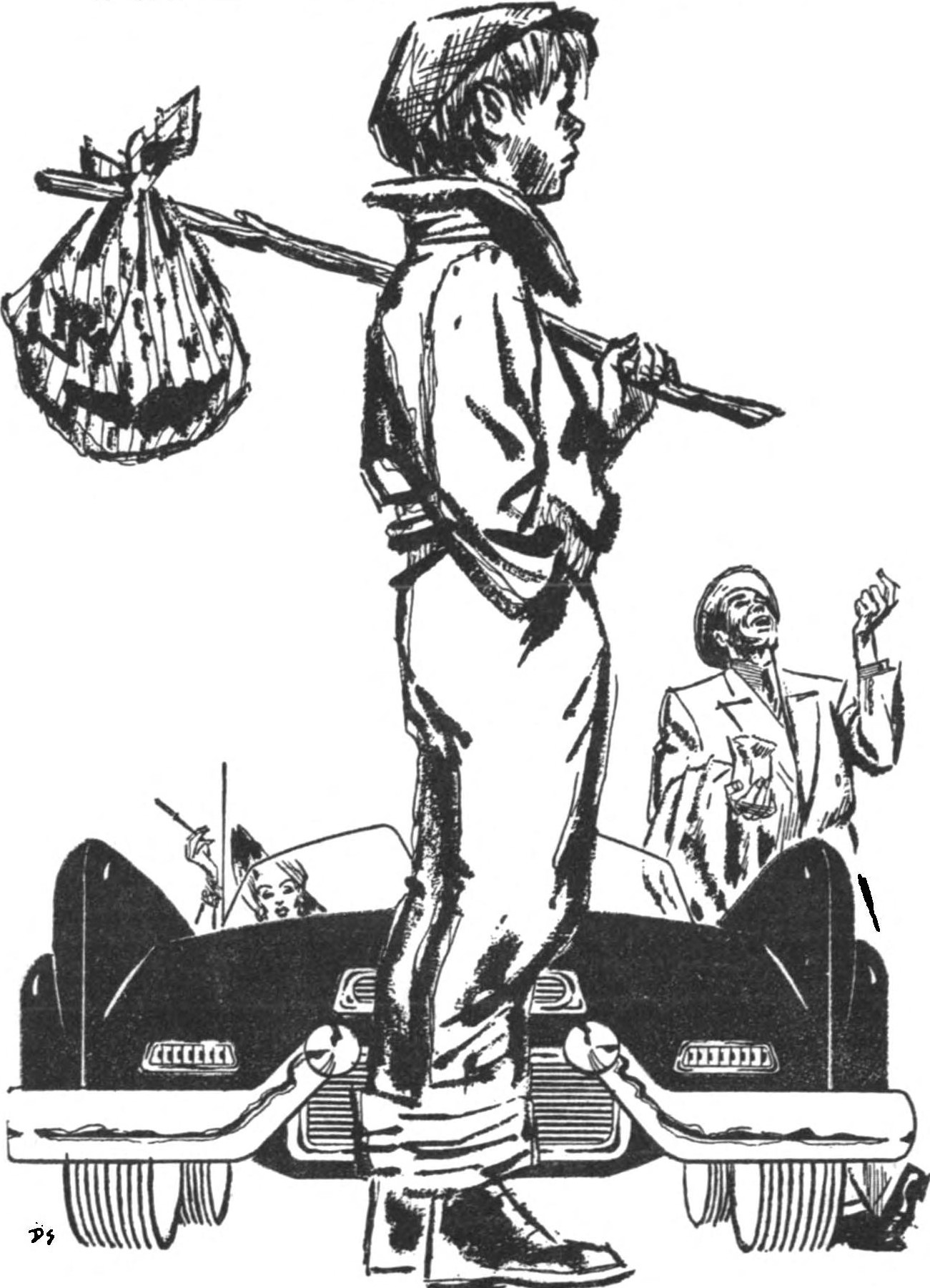

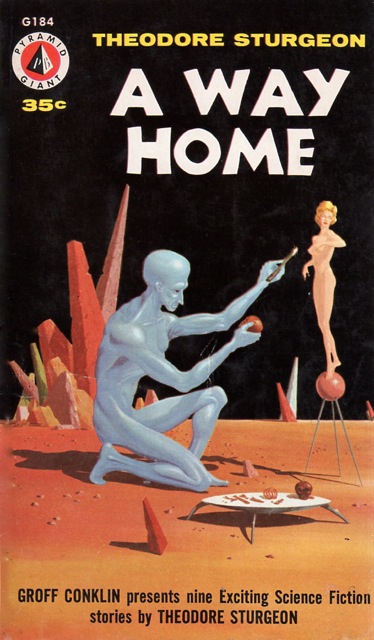

The Way Home, by Theodore Sturgeon

Cover art by Barye Phillips.

This quiet story comes from the April/May 1953 issue of Amazing Stories.

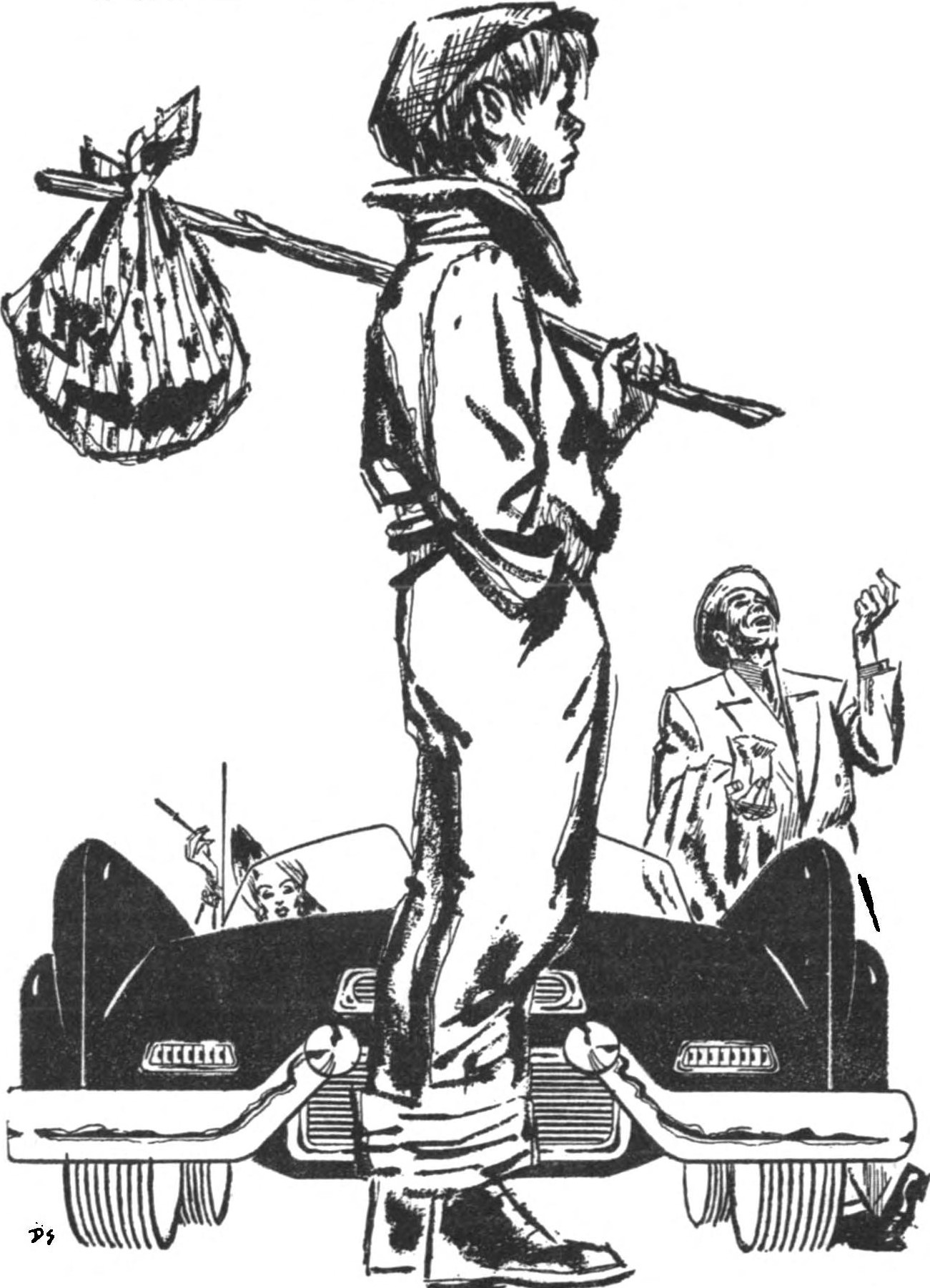

Illustrations by David Stone.

A boy runs away from home. Along the way he meets a wealthy man and his glamourous female companion, in their fancy car; a man with an injured hand who has been all over the world; and a pilot in a beautiful airplane. Without giving too much away, it's clear from the start that these men represent possible future versions of himself.

Is this the road to the future, or to home?

Like Asimov's story, this piece has already appeared in two of the author's collections, but with a slight change in the title.

Cover art by Mel Hunter.

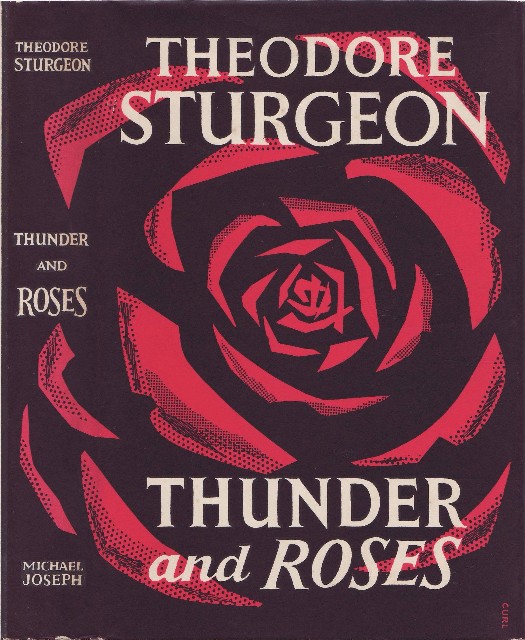

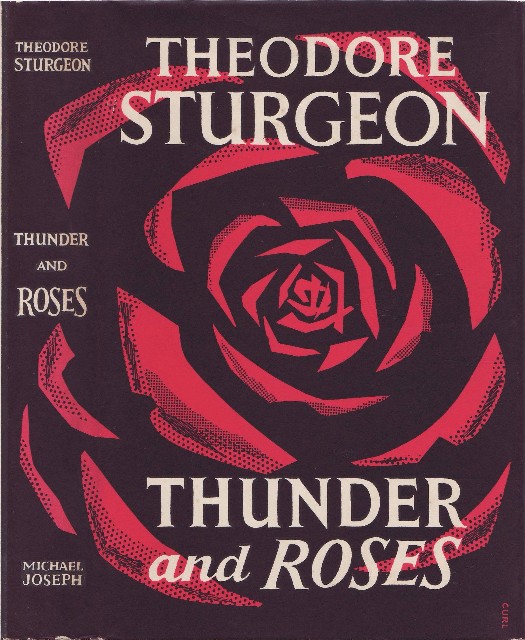

(I'm not sure if I should really count these as two different collections, because all the stories in Thunder and Roses already appeared, along with others, in A Way Home. Such are the vagaries of the publishing industry.)

Cover art by Peter Curl.

In any case, this is a beautifully written little story, subtle and evocative. To say much more would be to ruin the delicate mood it creates.

Five stars.

Worth Tuning In Again?

Cartoon by somebody called Frosty, from the same magazine as Satan Sends Flowers.

I wouldn't call this issue bad at all, although there were a couple of disappointing stories. It's no big surprise that the Simak and the Sturgeon were excellent, and Finlay's art is always a delight. It's enough to make you want to tear yourself away from all those reruns on television and turn to some literary reruns instead.

In the world of cuisine, reruns are known as leftovers.

Tune in to KGJ, our radio station! Nothing but the newest and best hits! Even the reruns are great!

![[December 20, 1966] Above and beyond (January 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i> and a space roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661220cover-656x372.jpg)

![[November 22, 1966] Ha ha. Very funny. (December 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661122cover-661x372.jpg)

![[October 22, 1966] Why Johnny Should Read (November 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/661022cover-653x372.jpg)

![[September 22, 1966] True Idols (the Isaac Asimov issue of <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660920cover-659x372.jpg)

![[August 24, 1966] Fantastic Voyage lives up to its name!](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/t9MuMN1-672x372.jpg)

![[August 20, 1966] Looking forward, looking back (September 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/660820cover-672x372.jpg)

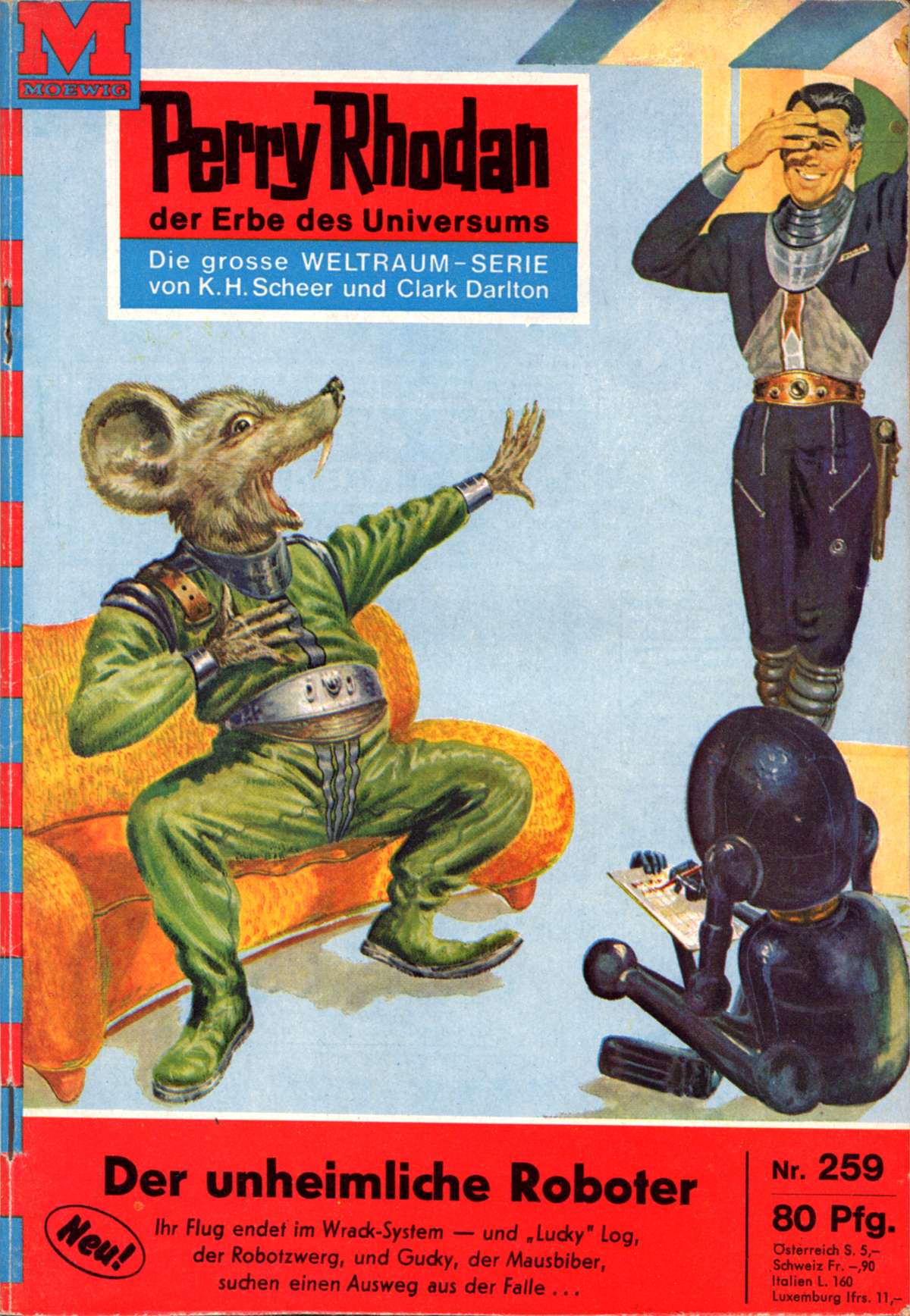

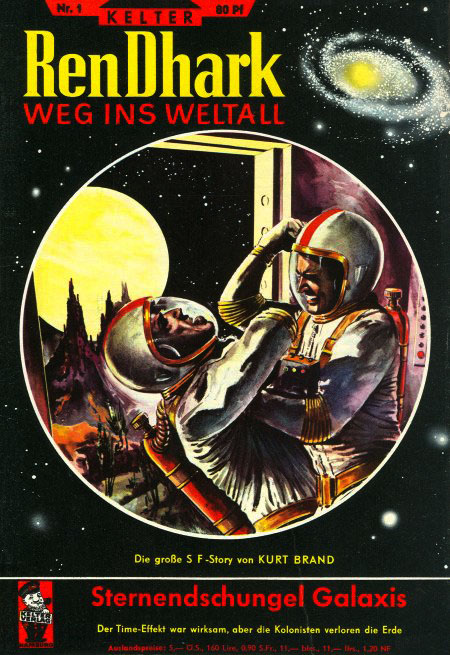

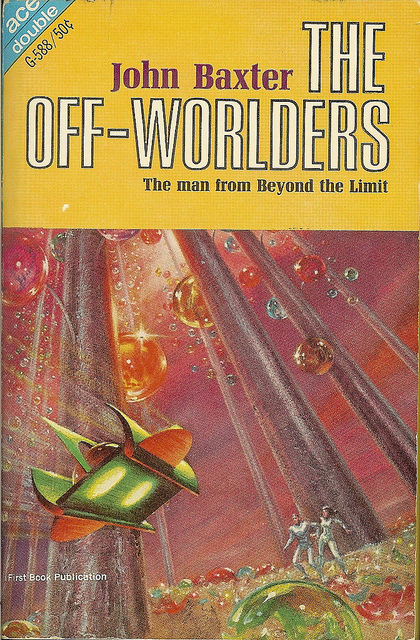

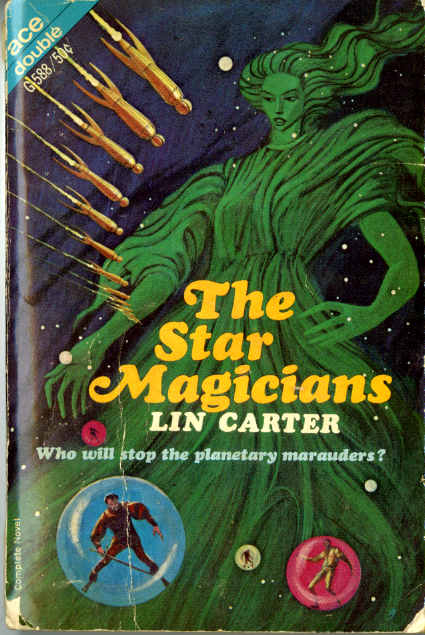

![[August 14, 1966] So Bad It's Hilarious (<i>The Star Magicians</i> by Lin Carter/<i>The Off-Worlders</i> by John Baxter (Ace Double G-588))](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/lin-carter-the-star-magicians-425x372.jpg)

![[July 20, 1966] An Endless Summer (August 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660720cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 16, 1966] Calm Spots (July 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660616cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1966] Summer Reruns (July 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/fantastic_196607-2.jpg)